“There will be no wedding here,” my father said, and the ballroom went honest in a single breath. The violins froze. The up‑lighting stopped pretending to be moonlight and turned into light. A hundred chairs remembered they were rentals. Somewhere near the bar, a single champagne flute chimed against a plate as if a nervous hand were asking permission to tremble.

Three months earlier, they’d stolen my house.

The decree that gave it to me was embossed and boring and beautiful, a Travis County judgment with a line the judge had read aloud like a promise: The marital residence shall be deeded to the minor child, Evelyn Reed, to be held in trust until the age of majority, trustee to be appointed from the paternal side. On the day my parents signed, Aunt Carol took my mother to a UPS Store where a woman with a stamp notarized a grant deed into the Irrevocable Housing Trust for the Benefit of Evelyn Reed. Carol kept the original in a fireproof bag alongside birth certificates and the photo of me losing a tooth in a T‑shirt that said GIRLS INVENTED MATH.

The house on Brushy Creek wasn’t big. A porch swing. A kitchen whose faucet wheezed at midnight. A magnolia that bloomed like it was trying to break your heart with the smell of memory. It was mine by paper and by the way I knew which cabinet held the oregano and where the eaves leaked when rain came sideways. When my mother married Victor Grady and brought his son Caleb into the house, the deed didn’t change. Just the air did. Victor ran a used‑car lot off 183 and liked rules that sounded like kindness. No shoes in the living room, sweetheart. No locking doors, kiddo. Families don’t hide from each other.

Caleb was six and sticky and sunlight. He called my mother Mama by the second week and called Victor Dad and called me Evie as if my name were a toy he was allowed to borrow. My mother called him “my champion” and called me “my rock,” which is another way of saying Please be the thing I stand on.

It’s remarkable how fast love can be redistributed when people decide you can carry more than your share. By the time I graduated, I had learned to set the table, to set my jaw, to set aside. Victor liked to say team player. He said it when the dishwasher flooded and when Caleb needed a ride and when he floated the idea of moving to Cedar Park because the schools were “better for our boy.”

“Our?” I asked once.

“Your mother and I,” he said. “And our boy.”

The first time he slid a leather folder across the table, the candle smelled like cinnamon and good intentions. “Housekeeping,” he said, tapping the page that said Durable Power of Attorney. “Just so your aunt doesn’t slow the bank down. We refinance, lower the monthly. Caleb will need a car.”

I took the folder to my room and called my father in a motel in Abilene. TV baseball murmured behind him. “Don’t sign a suitcase you don’t control,” he said. “That’s what a POA is. You hand someone a bag and they fill it with whatever they want.”

I went back to the kitchen and put the pen down. “No,” I said. It was small and heavy. My mother smiled like I’d declined a cookie. “Of course,” she said too brightly. “Another time.”

Another time arrived without me. A mobile notary named Sheryl came at 9:07 p.m. with a purse full of stamps and a smile that said she’d rather be home. I was working a Saturday shift at the dental office, counting cotton rolls. Sheryl stood in my mother’s kitchen under a light that hummed. Victor placed a photocopy of my learner’s permit on the table. “Power of Attorney from last year,” he said smoothly, which was a lie sandwiched around a truth. Sheryl didn’t compare signatures. She flipped her journal open like a waitress with a check presenter. She pressed a seal that sounded like a click too loud for a house at night and took a cookie for the road.

I learned about Sheryl later. What I learned first was the SOLD sign blinking in my lawn when I drove home that Tuesday in June. A man in a polo shirt with a clipboard said, “You must be Evelyn—your stepdad said you were taking the week to move.” My mother stood on the porch with hands clasped like prayer. “It’s going to be okay,” she said. Which is the sentence people use when they are already counting the exits.

If you’ve never watched your life get Boxed and Labeled and Hauled, you might think you’ll feel anger. Mostly you feel verbs. Wrap. Tape. Lift. Put this in the car. Put that in the truck. Victor was good at command. He told movers where to stack my boxes in the rental garage in Cedar Park. He told me it was temporary. He told me trust. He told me grateful. My mother wept when we left the porch, then laughed with Caleb when he found a Nerf bullet under a seat. “See? Signs,” she said, as if God communicated via foam.

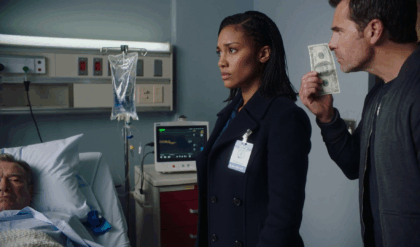

Aunt Carol showed up with binders and readers and a voice that made the air crisp. In twenty minutes she had the chain of title up on her laptop, the recorder’s stamp glowing like a bruise: a quitclaim deed notarized at 9:41 p.m., with a signature where my E veered like it had tripped. “Sheryl’s journal entry is sloppy,” Carol said, tapping the screen. “Not an actual ID check. If she was careless, she’ll lose her commission. More to the point: a court can unwind this.”

We hired Tessa Nguyen, a lawyer who wore boots to court and didn’t waste adjectives. She taught me to breathe with my belly and to bring receipts. She filed for a TRO on a Wednesday and got us in front of a judge on Friday. The courtroom smelled like pledge and dust and the faint iron of fountain pens. Tessa laid the story out on the counsel table like silverware: divorce decree, trust instrument, notary journal, the night in question, my signature that was not my signature.

The judge looked at me over half‑moon glasses. “Ms. Reed,” he said. “Which drawer in your kitchen holds the oregano?”

“Second to the right of the stove,” I said before I could be afraid. “Behind the cinnamon.”

“And the eave that leaks?”

“Northwest corner by the magnolia,” I said. I could hear my own heart like a bass behind bad speakers.

He nodded, satisfied with a truth he could taste. He signed the rescission order with a pen that clicked like the notary’s stamp had. “The forged deed is void,” he said. “Quiet title is granted. The house is yours.” His voice gentled, then edged. “However, the lender who in good faith satisfied the prior lien is entitled to equitable subrogation. An equitable lien in the amount of two hundred forty thousand dollars, plus interest, will attach to the property.”

Justice is a needle that threads through cloth you didn’t choose. I won a house and acquired a weight. In the parking garage Victor leaned against a column as if it were a podium. “Congratulations,” he said pleasantly. “You get your roof. Caleb gets his wedding.”

“You stole my roof to rent a ballroom,” I said.

“You make everything sound violent,” he said, smiling with all the muscles that mean I’m being reasonable. “We moved money where it was needed.”

My mother called that night sobbing into the phone. “Don’t ruin your brother’s day,” she hiccuped. “Please, Evie. He isn’t responsible. If you shut down the wedding, I—” She swallowed. “I won’t survive it.” Later she said she had pills. Later she said she’d leave a note. Later she said if people asked she’d say I hated my brother and that hate kills. It wasn’t negotiation. It was theater in a room with only one exit.

I sat on the Brushy Creek porch and watched dusk line the trees while the magnolia breathed sugar. Aunt Carol texted my father. I didn’t know until the next morning when he sent me a photo of a Buc‑ee’s beaver and then a time and an address. He had let his hair go gray. His eyes were the same: amused when the world behaved, furious when it didn’t, kind when it hurt. He slid pancakes across a diner table and waited while they cooled.

“They told you they’d die if you didn’t make their plans work,” he said when I finished. “They wrapped their choices in your softness.”

“She said she would hurt herself,” I said, because the smallness of the word Dad in my mouth embarrassed me.

“And you love her,” he said. “And you’re decent. And you’ll run yourself ragged paying debts you didn’t incur because someone cried near you.” He took a napkin and drew a square. “Here’s the house.” He drew a smaller square inside. “Here’s the lien. They arranged it so you carry both. We can’t change the past. We can rearrange the cost of their parade so it isn’t on your back.” He looked at me. “You don’t have to hurt them. You also don’t have to pay for their party.”

“They booked The Grove at Brushy Creek,” I said. “The Creek ballroom. Their contract has a morality/legal clause. If funds are illegal or disputed, the venue can terminate.” I knew because power lives in pages when you can’t find it in people. I had read every line at two a.m. and circled Section 12.4 like a talisman.

My father’s mouth did that soft, satisfied thing it does when he sees two paths and decides to build a third. “I poured that roof a decade ago,” he said, texting a number I didn’t know he still had. “If I can’t buy the place, I can buy its debt. Fast is clean.”

We didn’t speak logistics out loud in that diner. He didn’t say assignment of membership interests or deed in lieu or Secretary of State filing. He paid cash like always and said, “Wear something you can stand up straight in. And don’t run when they cry.”

The night Sheryl came back to me in detail when Tessa and I tracked down her journal. I could smell the cheap ink and the lemon oil my mother used on the table. I could see Sheryl’s tired smile and the way she didn’t look long enough at the ID copy to notice it was years old. I could hear the hush of the stamp and the way Victor slid a plate toward her because kindness is currency when you’re buying permission. The neighbor’s porch light had clicked on once—just once—and I ached that no one had knocked. The human heart has a keypad you only learn after you’ve watched someone enter the code too easily.

Rehearsal dinner smelled like smoke and molasses and men who say sons a lot. Victor raised a mason jar and toasted perseverance, the word men use when they want credit for surviving storms they built. Trevor, the groom, leaned toward Caleb when the AC hiccuped, his hand on my brother’s knee, calm, dependable, unaware of the ledger the room was becoming. A server with a dish rag tucked into her back pocket brushed past me and muttered, “You can’t mop a flood with a napkin,” and I had to look away so I wouldn’t laugh loud enough to shatter anything delicate.

The morning of the wedding was sun hammered into sky. Aunt Carol drove past my old porch; the new owners’ mailbox tilted like a shrug. “He’ll have his paperwork,” she said. “If he says it, he means it. Your father isn’t a shouter. He’s a finisher.”

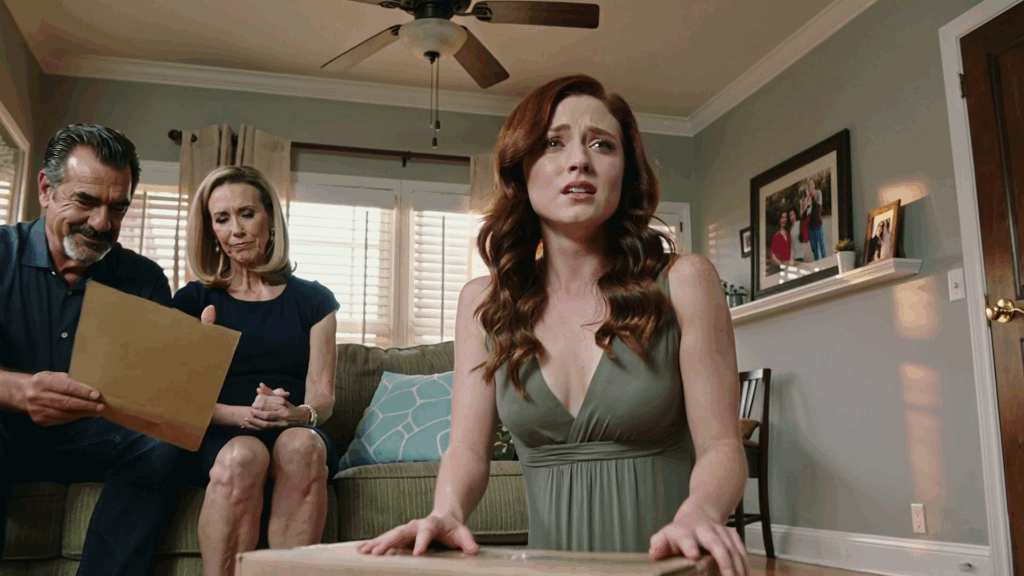

Inside The Grove, joy had been installed: bows on chairs, an arch rented by the hour, flowers pretending to be a forest. My mother pulled me behind a potted ficus near the catering door and let the fear pour out like Tupperware burped loose. “Please,” she sobbed. “If you love me, let today happen. After today I’ll make it right. I’ll fall on my knees and I’ll apologize and I’ll sign whatever—just let him have this.”

I wasn’t agreeing. I was triaging. If kindness is a tourniquet, I cinched it and hoped it wouldn’t cost the limb. “Okay,” I said, and the syllables scraped.

Victor took the mic and let his face sag into humility. “Ladies and gentlemen,” he said, voice warm as a staged living room. “Like all families, we’ve had misunderstandings. But we are a family. We’ve chosen grace. The wedding will proceed. Trevor will now exchange rings with my son.”

Rooms hum differently right before someone wins. The hum makes losers nauseous. The officiant lifted his book. Trevor squeezed Caleb’s hand. The violinist drew breath with her bow. My mother smiled at me with the pleased relief of a woman who believes the storm obeyed her. I tightened my grip on my clutch to keep from taking the microphone and burning the room down with a lighter and a truth.

The back door opened. My father walked in wearing a navy suit and a tie the color of patience, carrying a leather folio like a man who keeps his weapons oiled. He didn’t look at me first. He looked at the stage and at Victor and at my mother and at my brother and at the man about to marry him. Then he looked at the microphone and didn’t ask permission.

“There will be no wedding here,” he said. The sentence landed like an axe into a stump: clean, decisive, final.

Victor laughed as if a stranger had wandered into his living room. “Sir, this is a private event. We are in the middle of a ceremony. As I was saying—”

“As you were saying,” my father said mildly, “you were about to bless the spoils of a fraud with a rented arch. We won’t be doing that.” He nodded toward the side door. A woman I didn’t recognize stepped forward with a folder and a lawyer in tow. Her name tag read OLIVIA. She had the face of someone who has put out a ballroom fire without raising her voice.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” Olivia said into the house mic, professional but not unkind, “on behalf of The Grove at Brushy Creek, we are terminating this event effective immediately pursuant to Section 12.4 of your Event Agreement—the Morals & Legality Clause. We have received credible documentation that funds used to secure this event are the proceeds of a disputed, rescinded property transaction, and continued service would expose this venue and its staff to liability. Per the contract, all services cease now. The deposit is forfeited. Liquidated damages equal to thirty‑five percent of the food‑and‑beverage minimum are due.”

The lights changed the way lights change when a show ends: romance off, truth on. Bar taps closed. A server with a sparrow tattoo looked at me and we shared the glance people share when a script flips and they were secretly rooting for it. Murmurs thickened. A camera lens clicked and then stopped clicking, as if even a machine could tell when a moment didn’t want to be captured.

My father opened his folio and laid out copies like place settings. “Chain of title,” he said. “Divorce decree. Trust. The forged deed a notary stamped at nine forty‑one p.m. Rescission order. Quiet title. And here—” He tapped what had taken three weeks of sleep from me. “—the equitable lien that means my daughter is carrying two hundred forty thousand dollars of weight she did not choose. If you paid for any of this with that money, you did not pay.”

Victor’s smile drained. “This is outrageous,” he began.

“Don’t say outrageous,” Dad said gently. “Say inconvenient. Outrageous is a towed car from a Saturday matinee. This is the foreseeable consequence of theft.”

Trevor looked at Caleb, panic and decency wrestling. “Caleb?” he asked. “What is he talking about?”

Caleb swallowed like a boy with a marble in his throat. “We used the house money,” he said. “It was family money.”

My mother stepped forward, velvet and plea. “Daniel,” she said, making his name into a prayer and a weapon. “Please. Not here. We’ll fix it. The boy—”

“The boy is a man,” my father said. “And he can sign his name.” He placed two slim packets on the edge of the stage. “Option one: you sign this confession of judgment now, acknowledging that the equitable lien falls on those who benefited, not on my daughter. You agree to repay and to cover her legal fees. Option two: we file this temporary restraining order in the next twenty minutes, freezing your accounts and the accounts of anyone acting in concert with you. That includes vendors and the church that agreed to route a portion through its music fund to make it look like donations.” He glanced at my mother on that last word. She flinched. “Don’t insult me by denying it, Susan. You were never good at laundering even your feelings.”

Two men in shirtsleeves carried a small metal case to the front. The jeweler’s representative lifted a document for Olivia, then the officiant, who stepped back like it might bite. “Writ of replevin,” the rep said evenly. “In re: ring, cushion‑cut, one point four carats, purchased with funds later traced to a disputed transaction. Sheriff’s deputy is on site.” The deputy beside him had her hair in a tight braid and a voice like a calm lake. “We’ll do this respectfully. Everyone here is a person.”

Trevor’s hand hovered over his pocket and then retreated. Caleb made the sound of a tire giving up. The ring went into the case as gently as a sleeping thing. Someone turned off the Sterno flames under the chafers. The DJ coiled a cable like a snake he intended to relocate, not kill.

“You’re not the law,” Victor said to my father, moving toward the packets as if his body language could tear paper. “You can’t just—”

“The law is the law,” my father said. “I’m a man who read the contract and the chain of title and, as of 8:43 a.m., a man who owns this venue.” He let it sit. “Olivia will show you the Secretary of State filing if you think I’m only a suit with a voice.”

Olivia raised a page with a stamp that means nothing to the uninitiated and everything to those who sign paychecks. “Change of manager on file. New registered agent. Effective today.”

Victor snatched the confession of judgment like a shield. My mother tried to take it and he slapped her hand without looking at what it was doing. Caleb stared at the ring case as if he could will it to remember him. Trevor’s shoulders sagged. He looked at me and said the last true thing he would say to me for a long time. “I didn’t know,” he said.

My father turned to me then. The ruthlessness left his face like tide sliding off rock. “You okay?” he asked. The question cracked something in me softly enough to let the light in. I nodded. “Stand with me,” he said. Not because he needed my courage. Because he wanted me to know I had some.

My mother tried one more performance. “See what you made him do?” she whispered, eyes glossy. “He’s humiliating us. For what? The judge gave you the house. Why this?”

“Because there’s still a lien that puts the weight of your choices on my home,” I said, steady from the spine. “Because you told me if I spoke up you’d die. Because you made me pick between being kind and being safe. I’m done picking wrong.”

She looked at the deputy and at the ring case and at Trevor and at Victor and at the ceiling where the chandeliers pretended to be constellations. Then she signed. Susan Grady, in a careful script that belonged to the girl she’d been before all of us had disappointed each other.

“Thank you,” Olivia said, and meant it. The venue counsel slid the packets into his briefcase like a baby into a pew. The lights went neutral. The flowers looked embarrassed to still be blooming.

Guests left in trickles, then streams. Someone attempted a slow clap and it died mid‑air like a bird that hit glass. Outside, heat wobbled off the blacktop. The world did not end. It rarely does when you’ve been waiting for it to so you can feel justified. It simply rearranged itself so the load‑bearing walls were where they belonged.

In the lobby Victor tried to forgive me like a man playing generous. “Family,” he said, as if saying it were sacrament. “We’ll recover from this.”

“You’ll repay what you owe,” I said. The sentence tasted like copper and relief. “Then we’ll see what’s left.”

Caleb hunched by with his shoulders up around his ears. He had always been bounce. He would bounce again, just not toward me. My mother squeezed my hand and said, “Don’t make me your enemy,” like a prayer and a threat and a prophecy. “I don’t have to,” I said. “You keep volunteering.”

My father put a cool fob in my palm. “You’re going to sleep tonight somewhere you don’t have to look over your shoulder,” he said. “We’ll deal with the lien. We’ll deal with the roof. But not in a house that remembers too many threats.”

“Where?” I asked, the question a breath I hadn’t meant to hold.

“A place I bought this week,” he said. “West of here. A little high on the hill. No one knows it but us.”

The house smelled like cedar and fresh paint and the possibility you only smell when a space hasn’t learned your name yet. He showed me the main shutoff and the breaker box and the water heater valve because if you’re going to own a house you should own its bones. We sat on the porch swing and let the chain complain. “I bought The Grove because it was fast,” he said. “Because they were going to make you pay for their parade and I couldn’t fix the past but I could fix that. I’ll sell it next quarter. Unless—”

“Unless?” I said, smiling at the shape of the word.

“Unless you want to run it for a while,” he said. “Olivia will teach you. Hospitality is logistics with better lighting and more forgiveness. The work will steady you.” He hesitated. “You don’t have to say yes. No is allowed.”

I thought about seating charts and linen deliveries and fire code and the way joy is built by noon and taken down by midnight, and how someone has to check the generators when the band plugs their amps in like Christmas. I thought about years of setting tables and lowering my voice and carrying other people’s happiness like a tray I wasn’t allowed to spill. “Yes,” I said. “For a season.”

The season lasted. A quinceañera where a father danced like he’d saved his knees just for that night. A Saturday storm wedding we moved inside in twelve minutes while the bride cried relief into a towel. I learned to speak florist, DJ, Fire Marshal, and to read bridesmaids’ blood sugar from fifty feet. I kept safety pins in a pouch that said I DO in rhinestones because irony sometimes keeps you kind. I wrote READ THE CONTRACT on a whiteboard near the loading dock and underlined it twice.

We serviced the lien. It didn’t vanish. It shrank from a mountain to a hill you can walk before coffee. The venue’s counsel reminded Victor that a confession of judgment can become a lien against his toys if he got cute. Checks arrived with grudges attached. My mother’s texts oscillated between contrition and accusation like a ceiling fan that won’t decide which way is summer. Caleb showed up with Whataburger and said, “I didn’t know it would be like that,” and I believed him because consequences are maps you don’t read until you get lost.

Trevor married a man from his gym in a backyard with fairy lights a year later. The invitation was a watercolor of a tiny house with a lemon tree. I pinned it to the corkboard in my office like a good omen and mailed a Home Depot gift card. He wrote: Thanks for the second chance you didn’t know you gave me. Also, your place is booked through fall. Good for you.

Aunt Carol retired and grew tomatoes that looked like they were running for city council. Tessa sent a New Year email that said wary isn’t paranoid and I sent her a cake that said THANK YOU FOR THE WORDS THAT HELD. My mother started seeing a therapist because a church friend told her to. She sent me sunrises with verses and then asked for a loan. I said no. She said I was like my father. “I hope so,” I answered, and meant it.

Sometimes, on quiet Thursdays, I walked the old sidewalk on Brushy Creek and watched the new owners’ cat patrol the porch rail like a sentry. The magnolia still bloomed audacious. The eave still leaked if rain came crosswise. The house didn’t know my name anymore. That was okay. I had lived inside a sentence for a long time. Now I lived in paragraphs that led somewhere that wasn’t a hard stop.

On the anniversary of the wedding that wasn’t, my father and I sat on The Grove’s back steps and listened to the river complain about rocks. “Do you ever think we were too harsh?” I asked, because fairness is a habit more than a destination.

“Every day,” he said. “That question is the fence that keeps us out of the yard where the people who don’t ask it live.” He handed me an iced tea like communion. “You want the real reason I said that line?”

“I think I know,” I said.

“Say it,” he said gently.

“Because I’d learned to vanish to keep other people in the room,” I said. “And you taught the room to make space.”

He smiled. “Also because contracts are fun when you’re on the right side of them.”

A bride once arrived without a bouquet because the florist’s van found a pothole big enough to eat. I raided the landscaping with scissors and a plan. We made six bouquets out of eucalyptus and white roses and the audacity of adaptation. We gave the extra to the mother of the bride, who cried the way my mother cries and then hugged me the way mine did not. Two truths shared a chair and didn’t fight.

One Saturday, a band blew a circuit and Olivia and I ran an extension like we were laying fiber across a war zone. Another night, a groomsman broke a chair and apologized like he’d hit a mailbox. I told him chairs forgive when people don’t. He tipped the staff an apology and I wrote BE KIND on the whiteboard under READ THE CONTRACT because on some weeks you need both.

I saw Sheryl once at H‑E‑B, comparing prices on strawberries. She didn’t recognize me. I recognized her hands. I thought about walking up and telling her she had pressed a seal on a life and that life had survived anyway. I let her pick fruit in peace. Not every wrong needs your lecture. Some need your absence.

We finished paying the lien the spring the magnolia outdid itself. The title company emailed me a PDF stamped PAID IN FULL and I stood at the back door of The Grove and let the air pass through me like an exhale I had been saving. I wrote on the whiteboard: DON’T RUN WHEN THEY CRY, and under it, STAND WHERE YOU CAN SEE THE WHOLE ROOM.

My father sent me an invoice meant for a lumber supplier because he never remembers to switch contacts. I sent back a photo of a napkin with a square and a smaller square inside it and wrote you drew this once and then you built it. He replied with a thumbs‑up and a beaver emoji because some jokes never get old.

The night before our first Pride event, two teenagers practiced a first dance on the asphalt, earbuds in, arms awkward and hopeful. I turned the parking lot lights up a notch and pretended not to see. The boy dipped the boy and didn’t drop him. I wished them good wrists, better friends, and the kind of love that forgives without obliging. Inside, Olivia clicked off the last chandelier and waved. The creek kept telling its same old story about rocks and time.

When I lock up at the end of a night, the click runs up my arm like a pulse. The room goes honest, then dark, then calm. The world does not end. It simply waits. And in the morning, there’s coffee and a squirrel attempting something ambitious on the oak. He fails, and then he tries again, and then he makes it and sits there like he knew he would all along. I laugh out loud with no one to hear and write a new line on the board because weeks require mantras the way ballrooms require exits. Some days it’s Read the contract. Some days it’s Be kind. Today it’s this: You don’t have to vanish to keep the lights on.

If anyone ever asks me what the most beautiful sentence I’ve ever heard was, I’ll tell them it was the one that stopped a wedding and started a life. And if they ask how long it took to learn its truth, I’ll say: exactly as long as it takes to thread a needle through a house and pull the cloth tight enough to wear.