Nashville woke like a board of old cedar—grain rising, knots shining where the light struck. The Cumberland slid slow as honey under bridges, and on Music Row the brick buildings had their own breath, that faint smell of coffee, lacquer, and paper contracts. Lena Hart stood outside Studio B, coat unbuttoned in the mid‑March chill, listening to the city tune itself: trucks down Demonbreun, a pedal steel from somewhere upstairs, and the ghosty click of a tape splice in her head.

Her father used to say: Trust the meters, not your panic. When the VU needles float like swimmers in warm water, you’re close. When they slam red, you’re lying to yourself.

Inside, the past had been boxed and numbered. Bankers boxes stacked shoulder‑high, masking tape labels in her aunt’s careful print: HART, TONY—MASTERS 1978–1993. Lena’s palms itched. It wasn’t ownership; it was custody. It felt like the difference between holding a candle and holding the sun.

Her cousin was late on purpose. He had a talent for it. He also had a talent for grinning like a man who thought mirrors were invented to applaud him.

He arrived with a camera crew.

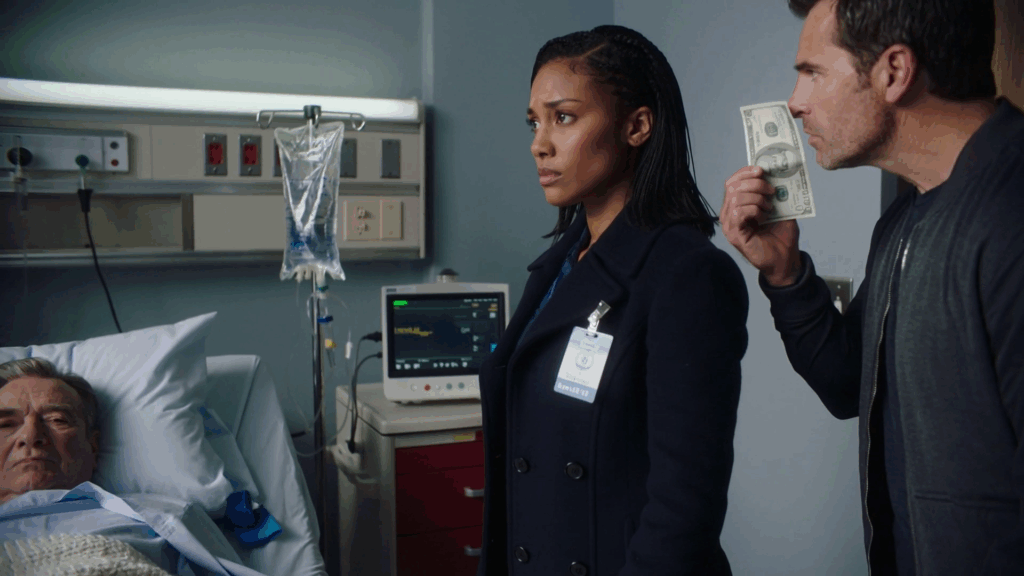

“Family day,” he announced to the lens before acknowledging Lena. “Music Row royalty returning to the scene. I’m Jax Hollister, producer, entrepreneur. And this—” He threw an arm toward the boxes, toward the air around them, as if gesture could sign a deed. “This is legacy. The Hollister brand is expanding. We just finalized acquisition of the Hart catalog for—” he paused, savoring the beat, “one American dollar.”

The camera operator zoomed. Jax flipped a single bill like a magic trick and tucked it into his shirt pocket.

“Say hi to the fans, cuz.”

Lena felt her cheeks go cold, then hot. “You ‘acquired’ what wasn’t yours to sell.”

Jax’s smile sharpened. “Look, I get that you’re sentimental. But business is business. Uncle Tony signed. People sign things when they need help. You weren’t around then.” He leaned toward the camera. “And Lena is a talented—what do you do again? Hobbyist?” He snapped. “Right—audio… volunteer. She blogs about old machines. Cute.”

“Audio archivist,” Lena said, and even that felt too small. “I restore master tapes. I know what a half‑dB at 10k means to a voice like Dad’s.”

“Your dad needed management,” Jax replied. “We provided it. Now the world gets to hear his music, properly branded. I’m not the bad guy here.” He pivoted back to the lens. “Report to follow.”

He swept out like he was late for his own legend. The camera crew followed, their cables snaking across the threshold.

When the door clicked shut, the room had that after‑storm calm. Lena stood very still, hands on a banker’s box, the cardboard soft under her fingers from a decade of humidity and hope.

The VU lights on the old Revox in the corner were cold. In her mind, they glowed a warm, living amber, like two eyes that knew her name.

—

Two days later, the first wound arrived quietly: Spotify pushed an update. Under Ain’t October Forever and Carpet of Red Leaves, the artist field no longer said Tony Hart. It said Hollister Records Presents. On the songwriter line, a new gray attributions box had appeared: Adaptation & Production: JAX HOLLISTER.

She stared until the letters blurred and the playlist scrolled past. Her phone buzzed with texts—fellow engineers, old bandmates of her father, a kid from Belmont who’d interviewed her about tape baking last fall. Did you see? Is this legit? Do you need a lawyer? I’m sorry. This is wrong.

It got worse. The vault at her aunt’s had a keypad Jax now controlled. When Lena keyed in the old numbers, the red light blinked an indifferent NO. Her aunt’s number went to voicemail.

And then the email: Notice of Control of Masters. Boilerplate and bluster. Plain type, ornate arrogance. “Any duplication or creation of derivative works from Hart masters is prohibited. All assets have been transferred to Hollister Records. Please coordinate any requests through our office.” It was signed, in swoop and flourish, by Jax.

Lena set her phone face down on the bench by the studio’s machine room. She watched dust drift through a shaft of morning light and settle on the Revox’s headblock. The spindles looked like two patient hands waiting to receive thread.

Her father had not raised her to accept bad tape, or bad law.

She pulled a milk crate from under the bench—LENA—TOOLS sharpied on the side. Demagnetizer. Lens wipes. A small phillips screwdriver worn smooth by three lifetimes of use. At the bottom, wrapped in a cloth diaper like a baby, a splicing block.

When panic rises, you make signal. She needed steady tone in her ears, a thing she could control.

The door to the control room eased open with a hesitant creak. “Place smells like coffee and ghosts,” said a voice Lena recognized from a hundred publishing meetings where she’d quietly carried the DAT while men smiled over paperwork. “I thought maybe you’d be here.”

Edwin Calloway had hair like old silver strings on a guitar and a face that had learned how to be kind without being soft. He’d been one of the city’s fiercest entertainment attorneys until a health scare five years back had nudged him into semi‑retirement. He still consulted, but only for people he could love without lying to.

Lena felt her throat tighten. “You saw.”

“I saw,” he said. He came to the bench, palms on the edge the way men lean at hospital beds. “I also saw an interview where a young man pronounced ‘catalog’ like a trophy and used the word ‘monetize’ as a verb. We should put that out of its misery.”

“I don’t know if I can fight him,” Lena said, and the confession felt like flipping over a tape you weren’t sure would still play. “He has the vault. He has my aunt’s signature on something. He’s already rewriting credits. All I have are stories and a machine.”

Edwin’s eyes went to the Revox. “That’s not ‘just’ a machine. That’s chain of title with a heartbeat.” He eased onto the stool. “We don’t fight him where he’s strongest. We fight where the law is stubborn and the truth is loud.”

He reached into his battered leather bag, withdrew a thin red book with a cracked spine, and set it on the bench. Title 17—Copyrights. Tabs stuck out at odd intervals like a porcupine. “Ever hear of termination of transfer?”

“Vaguely,” Lena said. “Thirty…five years?”

“Seventeen U.S.C. § 203,” Edwin said, touching the page like a hymn. “If your father signed away rights to his compositions, he—or you, as heir—has an inalienable right to terminate that grant after thirty‑five years, within a specific window. You serve notice, you wait the statutory period, you reclaim. Nobody can force a waiver. I have won cases with less.”

“What about the masters?” Lena asked. “The physical tapes? The sound recordings?”

“The masters are a separate fight,” Edwin said. “But often the tail wags the dog. If the songs revert, the shine comes off any phony ‘acquisition.’ And if our friend’s one‑dollar miracle was never paid—if consideration didn’t actually change hands—or if your father lacked capacity, we have state contract law on our side. Tennessee courts do not rubber‑stamp hallucinations.”

He slid a yellow legal pad across the bench. “We’ll need dates. Recording logs. Original publishing splits. Any paper between your father and Hollister—label, management, ‘family agreements.’ Chain of title is only as strong as its weakest paperclip.”

Lena exhaled. The room felt different. Not safer. Just truer. “I can do dates.” She looked at the machine again. The Revox’s VU meters were dark but she could see their afterimage the way you see a loved one in a crowd even after they’re gone. Trust the meters.

Edwin rose. “Meanwhile, make music. Not for Spotify. For court. For the world. Reconstruct what you can. You’re an archivist. Bake the tapes. Transfer at 24/96. Restore, but don’t erase the age. Judges are humans; they hear honesty.”

“Baking takes time,” Lena said. “I need a clean convection oven. Low and slow. Two hundred degrees Fahrenheit, no more than eight hours depending on binder breakdown. And those reels have been sitting thirty years.”

Edwin smiled. “Good. Do the work that can’t be faked. I’ll do the work that can be proven.” He tipped his head toward the door. “I’ll send a letter to Mr. Hollister to preserve evidence. Spoliation’s an ugly word and juries hate it.”

When he left, the studio seemed to grow a spine.

Lena rolled the Revox to the center of the control room and popped the head cover. The parts were named in her head like old friends: capstan, pinch roller, lifters, heads—erase, record, playback—guides, idlers. She threaded a sacrificial leader through, checked azimuth with a test tape, and tapped the spindles with her fingernail. They rang like coins.

On the shelf behind the console, a brown carton labeled HART—1/4″ ROUGHS waited like a letter from a war. She slit the tape with a razor and lifted out the first Ampex reel. A yellowed note was tucked under the flanges: Careful, kiddo. 456 is a gummy liar. Bake me. Her father’s blocky handwriting.

She laughed, then cried, then set the oven.

—

The montage of work saved her.

A dawn of aluminum reels on the counter like a silver harvest. Lena weighed tapes in her hands the way bakers weigh dough without thinking about it. She wrote times and temperatures on blue painter’s tape and stuck them to lids. Old adhesives exhaled a smell you could taste at the back of your throat: vinegar, dust, the ghost of cigarettes no one admitted to.

She baked in shifts: 54°C for four hours on the worst of the Ampex 456s, less for the BASFs that had aged like saints. Between loads she cleaned the Revox’s guides with 99% isopropyl until the cotton swabs came up pristine. She demagged the heads with slow, circling passes, electricity singing faintly like a bottle fly.

In the spare bedroom she’d turned into a capture suite, she built a chain like a recipe. Revox A77 to an Apogee Symphony, clocked stable, input gain set conservative. Capture at 24/96 in WaveLab, building folders named like prayers: TonyHart_Tape01_SideA_Raw. She listened to tone—1k, 10k—and aligned azimuth until the top end opened like a window. She nudged EQ with a surgeon’s restraint, just a breath at 80Hz to warm the room, a half‑step tuck at 3k if a vocal scraped. She could hear when her father turned his head from the mic to grin at someone behind the glass.

She documented everything. Timecode slates. Take numbers. DDL of every file. ISRCs reserved for the eventual masters—unique twelve‑character fingerprints that would travel with a song like its true name. The International Standard Recording Code wasn’t romance. But it was proof, visible in a dropdown menu where too many people stopped reading.

When she found dropouts on an early chorus of “Last Song,” she didn’t panic. She built a comp from a later repetition, matched syllables like dovetails, and crossfaded with a splice that would hold steady down a bumpy road. She left the tape hiss where breath lived. Too clean and you could erase a person.

At night she logged into the PRO portal—ASCAP, where her father had registered his first barroom miracle and had been paid a check for $17.32 that he framed like a diploma. She updated contact info. She submitted cue sheets for old live shows where bars had collected fees and never reported. She built a spreadsheet of performances, a boring, beautiful ark.

On a Thursday, the oven beeped and the house smelled like pennies. She pulled a reel out bare‑handed, tested the binder with a fingernail, and found it no longer sticky. She set the tape on the Revox, threaded leader, and rolled. The VU meters rose in that honeyed, patient way, and her father’s voice entered the room as if there had never been such a thing as loss.

This is the last song I wrote before the fall, he sang, dry and close. I put the truth where the chords feel small.

Lena didn’t stop the tears. She rode gain with fingers steady as a mason string. She printed to file and put both hands on the console when it was done, forehead to knuckles like a benediction.

She wasn’t alone. Texts came in from a small, ferocious army. A steel player named Lupe who had backed Tony in the eighties and still carried a bar in her purse. A church sound guy from Smyrna who took classes with Lena last year and wanted to bring donuts. A professor from Belmont’s audio program who offered their lab oven after hours, no questions asked. “We’ve got a Studer A80 in the back if you need an A/B,” he added. “It’s lonely.”

The Revox watched from the corner with its two watchful amber eyes. Motif, Lena thought suddenly, the way writers talk about a word that repeats until it means more than itself. The machine wasn’t decoration. It was the quiet insistence that the story had a heartbeat independent of anyone’s signature.

—

Edwin moved like a patient storm. He pulled the 1989 management agreement from the courthouse records with a clerk he’d known since both of them had better knees. He found a “family agreement” drafted by Jax’s father—a document with rhetorical flourish and legal anemia—that purported to “assign” Tony’s “catalog” to “Hollister Holdings” in exchange for “consideration in the amount of one dollar and love of family.” He found no proof the dollar had ever changed hands. He found medical notes from two days before the signing indicating Tony had mixed Valium with bourbon in a way that would render judgment an exotic animal glimpsed rarely at dusk.

“Tennessee doesn’t invalidate contracts for being sentimental,” he told Lena, glasses low on his nose. “But it does require capacity. And consideration is still a bargain, not a bedtime story. Whether or not a dollar can be consideration, it must be real—paid, bargained for. If a thing is only said and never done, it is smoke. And the right to terminate a copyright grant after thirty‑five years,” he tapped the Code again, “cannot be signed away even if it were gold‑plated smoke.”

They calendared everything. Under § 203, notices of termination had to be served not less than two years and not more than ten years before the effective date, within a window anchored to the date of grant. Lena and Edwin built a timeline across the kitchen wall with painter’s tape and index cards. 1989: publishing deal. 1990–1991: first recordings that mattered. 1993: the year “Last Song” broke a little college station in Missouri and made Tony famous enough to be broke in more interesting ways. 2025: the current now, its window opening like a stage door.

They drafted termination notices on good paper, each referencing the section, the date of the original grant, and the works covered, with enough specificity to make a librarian smile. Edwin insisted on certified mail, return receipt requested, and on filing notices with the Copyright Office, because he had learned long ago that judges like evidence they can hold in their hands and squint at.

Lena signed with a Blue‑black Pilot pen because her father had liked how it dried. She held the pen a moment longer than necessary, as if there were a way to sign for two people.

—

“Play me a thing,” Lupe said on a Friday when the house was full of cases and cords. She had shoulders like a happy bull and wore her hair in a salt braid that could discipline the wind.

Lena cued an early mix of “Last Song.” The room fell into that respectful silence musicians keep like prayer. When the chorus hooked and refused to let go, Lupe’s head went down hard enough to be a nod and a sob at once.

“How do we beat a boy with money, sugar?” she asked when it was over.

“We don’t,” Lena said. “We make him irrelevant.”

That night, the Belmont professor sent a message: We’ve got an opening on Saturday afternoon at the Little Room—student showcase. If you wanted to test a mix on real speakers in real air… He let the ellipsis dangle like a fishing line.

“Not a show,” Lena wrote back, panic lighting in her chest. “I don’t perform. I measure.”

“Air is a measurement,” he replied. “And grief calibrated to joy is the most accurate meter we own.”

—

Jax’s videos multiplied like ambitious rabbits. He filmed in front of neon signs and in his car, where men go to announce things they haven’t thought through. “We’re bringing the Hart legacy into the modern era,” he told his followers, voice pitched in that confident sing‑song people use when they’re not sure but hope you will be. “We’ve already got sync interest from a major streaming series. Tony Hart’s stuff is going to finally earn real money.”

He posted a screenshot of an email from “Hollister Legal” to “Third‑Party Platforms” requesting that any “unauthorized Lena Hart uploads” be removed. He added a winking emoji.

Lena’s inbox dinged with notices: Content conflicts. Claims. She stared for a long minute at the ceiling above her bed, where water had once stained an asymmetrical cloud that now looked like a man trying to run underwater.

She opened WaveLab and worked.

—

The memorial was Lena’s aunt’s idea, pitched as a reunion and sold to sponsors as “Tony Hart—The Last Song, A Celebration.” It would be held in a small theater off 8th Avenue, the kind with velvet seats and a stage that knew what to do with footsteps. “Your daddy would hate it,” her aunt said on the phone in a voice hoarse with both grief and pride. “And he would show up and be perfect.”

Jax volunteered to produce. Naturally. He sent a deck with glossy photos and bullet points and a section called PARTNERSHIPS that made everyone feel like a product. He also included a slide titled Rights & Clearances that named Hollister Records as the sole gatekeeper of Tony Hart’s legacy, with a helpful arrow pointing to his own face.

Edwin sent back three sentences. “No one person is the sole gatekeeper of a man’s legacy. Certain compositions are subject to termination under 17 U.S.C. § 203; notices have been prepared consistent with statutory timelines. All parties are instructed to preserve evidence and avoid making claims that could be construed as misrepresentation under 17 U.S.C. § 512(f).”

Jax’s reply contained fewer words and more emojis.

Lena did not want to play. But she also did not want to watch someone else use her father’s music as a trampoline.

She set up the Revox on the kitchen table and stared at the VU meters until her breath matched their imaginary rise. Grief is noise. Love is signal. The machine would tell her when the ratio was right.

“Bring the Revox onstage,” Lupe said when Lena told her she’d been asked to say a few words. “Don’t sing if you don’t want to. Play the ghost. Let him talk.”

Lena swallowed. “I don’t want to make it about a fight.”

“It isn’t,” Lupe said. “It’s about a father and a daughter and a town that owes the both of them a listening.”

—

The day before the memorial, a courier knocked. He wore a tie too tight for his temper and handed Lena a thick envelope as if it had personally insulted him. Hollister Records, LLC—Demand to Cease and Desist. The letter threatened injunctions, damages, and a general apocalypse if Lena “exhibited, reproduced, or distributed” any Hart masters without Hollister’s permission.

Edwin read it twice, mouth flattening into a line that looked like a scar. “Paper roars,” he said. “Law walks.” He drafted a reply that morning: “Your letter presumes facts not in evidence. Please be advised that the physical possession of tapes is not ownership of underlying composition rights. Additionally, as you are aware or should be, termination of transfer notices under § 203 have been prepared and will be served within the statutory window. Claims to the contrary are noted for the record. Finally, if you intend to rely on a 1989 ‘family agreement’ for your chain of title, you should be prepared to demonstrate actual consideration and capacity. We require preservation of all related communications and accounting.”

He cc’d a Gmail address that belonged to a local reporter who wrote about music the way some people write about wars and who had a soft spot for men who told the truth only when they sang.

“Is this how we win?” Lena asked.

“It’s how we avoid losing before we arrive,” Edwin said. “The winning happens in rooms without trophies. Like kitchens.”

—

On the morning of the memorial, Nashville wore its spring like a good suit. The theater lobby filled with faces that had warmed Lena’s childhood: men with hands callused by strings, women with throats made famous by harmony. The air hummed with the particular electricity of a gathering that is both reunion and funeral—the desire to tell every story at once and the fear that telling makes them end.

Backstage, Jax preened. He wore a headset he did not need and gave notes to a lighting tech who had lit more rock gods than Jax had met. “We’ll start with a sizzle reel,” he told the small crowd of volunteers. “Tony moments. Then I’ll bring up the new era—the Hollister plan. Then maybe we let some old friends play a little.”

“Or,” said the lighting tech with studied gentleness, “we could let the music do the part where the music does the thing.”

Lena stood near the wings with her Revox on a rolling cart, hands on the handles as if she were guiding a dear but stubborn mule. Lupe tuned silently beside her, the steel’s bar clicking like a metronome when it kissed the strings.

Her aunt pressed a small velvet bag into Lena’s palm. “Your daddy’s razor,” she said softly. “The one he used to splice. He kept it sharp like a word.”

Lena felt the weight of it, the particular gravity of a tool that has cut only truth.

Edwin arrived like the chime of a clock you trust. He wore a navy blazer and a look that said nobody was going to be ugly on his watch. “I spoke with the organizer,” he murmured. “No sizzle reel. The program will open with a story and a song. Yours if you want it. Or I’ll tell it and you roll tape.”

Lena’s mouth went dry. She could say no. She could hide in the work. She looked past Edwin, past the curtain, past the rows of chairs, to a place onstage where the light pooled like a question. She thought of the VU meters—in her mind they glowed their gentle gold, waiting for input.

“Okay,” she said. “But I’m not singing.”

“You won’t have to,” Edwin said, and smiled like a blueprint.

—

They set the Revox on a stool at center stage like a guest of honor and ran a pair of lines to the house. The machine’s VU meters woke in actual light this time, bulbs warming to their old amber like the color of Tennessee whiskey held up to a kitchen window. The audience murmured. You do not see a tape machine in a place of performance unless a resurrection is scheduled.

The emcee spoke a few words about community and memory. Then he said, “Lena Hart would like to show you a thing her father taught her.”

She walked out carrying the velvet bag with the razor and set it on the console as if placing a photo on a mantel. She touched the Revox like you touch a friend’s shoulder so they know you’re real.

“My dad believed machines tell the truth,” she said, and her voice didn’t shake. “He also believed contracts don’t get to bully songs. The law agrees, eventually. Thirty‑five years is a long time to wait for right.” A small hum moved through the crowd—recognition that this was not only a memorial.

“He called this one ‘Last Song’ when he thought no one was listening.”

She pressed Play.

The room changed shape. Tony Hart’s voice was not the ghost of a voice; it was the air’s new purpose. He sang the same lines Lena had captured: This is the last song I wrote before the fall… I put the truth where the chords feel small… But in the theater, the words built ladders in strangers’ chests. Lupe slid in under the chorus with steel that sounded like the distance between what you wanted and what you got, and the audience met them with the quiet roar of people remembering who they were.

When the tape rolled to leader, Lena stopped the machine and let silence do its work.

Jax stepped into that holy quiet with the instincts of a man who sees a handshake as an opening to sell a hat. “Beautiful,” he said, taking center stage uninvited. “And exactly the kind of content the Hollister team is excited to—”

Edwin was beside him before the sentence finished, hand hovering near Jax’s elbow like a polite fence. “A moment,” he said to the audience without looking away from Jax. “There’s business to clarify.” He lifted a single sheet of paper, crisp and white, and held it so the stage lights caught the seal at the top. “Under 17 U.S.C. § 203, the heirs of an author may terminate prior grants of rights after thirty‑five years. Notices of termination concerning a number of Tony Hart’s compositions have been served consistent with statute. That means—” he turned to the room, his voice spreading gentle as butter, “the songs begin their way home.”

A murmur, this time brighter, a ripple like hands warming.

Jax smiled like a man on wet stones. “Legal processes are complex—”

“They are,” Edwin agreed, “which is why we keep them plain: a paper was signed in 1989 that purported to assign rights for one dollar. No dollar left any pocket. At the time, Mr. Hart was under medication that would render assent questionable under Tennessee law. Meanwhile, the termination rights cannot be contracted away. We’re not fighting you, Mr. Hollister. We’re inviting the law to do what it says.” He lowered the paper. “Tonight is about music. The paperwork goes where paperwork goes.”

Jax’s headset—prop, costume—caught a glint of light. He looked at the audience and calculated, badly. “We all want what’s best for Tony’s legacy,” he said. “I’ve produced major projects. I can modernize this.” He gestured to the Revox as if presenting a horse at auction. “We don’t have to worship equipment to honor art.”

Lena watched the VU meters. They were at rest, calm in their amber, ready for either rage or grace. She breathed until the needle in her chest settled.

“Jax,” she said—not into a mic, just into the air they shared. “If you return the photographs from my father’s sessions—the ones you took for your pitch deck—if you stop saying you ‘own’ his truth, I’ll credit you as production consultant on the releases you actually consulted on. Not as owner. Not as writer. As the person who, once, turned on a light and passed a cord. And I’ll grant a non‑exclusive license for educational use of Dad’s songs to the East Nashville School of Music. Forever and free.”

The offer hovered. It wasn’t strategy; it was a door.

Something flickered across Jax’s face—the knowledge that rooms sometimes turn on a sentence, and that he had been given one last good one.

He opened his mouth, but the emcee, to his credit, had already moved on. “Lupe, would you mind showing us how a steel can cut a cloud?”

The night returned to music. People sang with their hands in front of their chests, fingers curled like they were holding something invisible and warm.

Backstage afterward, Jax found Lena by the water cooler, where truth often rests before doing something brave.

“You can’t offer licenses,” he said, not loudly, as if shame were a language only they spoke. “You don’t own anything yet.”

“I can offer a promise,” Lena said. “And I did. It’s in front of witnesses. We all know what we heard.”

He rubbed his jaw. “You made me look like the bad guy.”

“You did that,” Lena said, and the softness in her voice made it hurt more. “I offered you a way to look like family.”

He stared at the Revox glowing in the corner like a campfire after everybody’s gone to bed. “I’ll send the photos,” he said. “The originals. I want my name somewhere. Not big. Just present.”

“Production consultant where true,” Lena said. “No more.”

He nodded, an adult signing for a package.

—

The story could have ended then and been enough for one life. But lawyers prefer endings with paper.

In the weeks that followed, Edwin filed the termination notices with the Copyright Office, stapled to cover letters that read like maps. Certified mail went to publishers who had learned to pretend surprise and to agents who never did. Return receipts came back with green cards signed by people whose only job on earth that day had been to make a mark acknowledging gravity.

A young associate at a big firm that handled Hollister’s affairs called Edwin with a tone that suggested both apology and hunger. “We’ve reviewed the 1989 ‘agreement,’” she said. “I can’t find any evidence of payment.”

“That’s because smoke doesn’t hold coins,” Edwin said, not unkindly. “Let’s discuss settlement pathways that honor the work and keep your client from promising what he doesn’t have.”

The associate cleared her throat. “There’s also the issue of Mr. Hart’s medical records.”

“Tennessee recognizes that people must be present in their minds when they sign,” Edwin said. “If you proceed, you’ll be putting capacity on the stand. Nobody likes that story.”

Silence, the useful kind.

“We’ll be in touch,” she said.

Lena kept working through it all. She logged ISRCs for each restored track, registering through US.ISRC.org and double‑checking that the codes embedded properly in WAV metadata. She filed work registrations with ASCAP, making sure splits reflected the men and women who had actually shaped the songs in rooms with coffee rings and duct‑taped mic stands. She wrote plain‑language notes for each song—who played, which machines, where in the room they stood—so that when a student fifty years from now opened a file they would find not just sound but place.

On a Wednesday, the Belmont professor invited her to guest‑lecture. She wheeled in the Revox and set it on the table like a friendly animal. Students leaned forward, phones forgotten. Lena showed them binder breakdown charts and played them before‑and‑after transfers, letting them hear how a careful demagnetize could bring back a consonant that held a man’s dignity.

“Why the Revox?” a girl in a denim jacket asked. “Why not a digital plug‑in that simulates all this?”

Lena touched the warm metal where the VU bulbs lived and smiled. “Because these weren’t simulations. And because the person who first said these things into the air believed this machine would tell the truth about him. That belief lives in the iron.”

Another hand, a boy with a baseball cap turned forward. “Are you scared you’ll lose? Like, the lawsuit?”

“I’m scared of forgetting the smell of my dad’s jacket,” Lena said, and the room breathed with her. “The law will take the time it takes. Meanwhile, I’m doing the part that holds.”

When she rolled the machine back to her car, she caught sight of a bulletin board in the hallway—flyers for shows, tutoring, open mics, and in the corner a photo tacked up with blue tape: Tony Hart at 27, laughing mid‑note, the Revox behind him like a lighthouse. The caption in a student’s neat print: Last Song, First Right.

—

One evening, as light fell through her blinds in gold slats, Lena sat at her kitchen table and spread before her the things that had tried to own her day: Jax’s latest DM, Edwin’s latest email, a postcard from the East Nashville School of Music with a crayon drawing of a guitar and the words THANK YOU MISS LENA written like a parade. She set the razor beside them all. She flicked its blade open, not to cut anything, but to feel its balance.

The Revox across the room ticked as hot metal cools. Its VU meters held their steady amber, less light than memory.

Her father’s voice lived in the house again, not as a ghost but as a choice. She could press Play and the air would fill with him. She could press Record and add herself—breath, hum, anything soft enough to sit beside him without asking for attention. She did neither. She just sat, the way a person sits when they’ve repaired something that wasn’t theirs to break and now must learn to live with the repaired thing without checking it every five minutes for cracks.

There would be a settlement paper soon, Edwin had said—language that drew boundaries around who could use the word “own” without lying. There would be a donation letter to the school for the non‑exclusive license, signed by someone who had never met Tony Hart and still knew he would have approved. There would be liner notes to write.

Lena closed her eyes and watched the VU meters in the dark of her lids, floating, responsive. When she opened them, the amber was still there, warm as a porch light left on for a person who might be late.

Tomorrow she would print reference CDs for older players who preferred to hear with their hands on plastic. Tomorrow she would file two more cue sheets and write to the journalist about telling the story without making anyone a villain except the slow stupidity of time. Tomorrow, if it was brave, she might sing a harmony line in the bridge of “Last Song,” just to see if the machine would hold them both.

For now, she whispered to the room the way you speak to a child you love: “Home.”

The Revox’s tiny bulbs glowed like yes.

The settlement did not arrive as a trumpet blast. It came like good weather—predicted, doubted, and then suddenly you were sitting on the porch without your jacket and realized you were not cold anymore.

Edwin called at 8:11 a.m. on a Monday, the hour when Nashville coffee shops do their best impression of courtrooms. “They blinked,” he said. “Bring your pen.”

At the firm’s conference room on the twenty‑third floor, the city looked arranged by a set designer with a bias for bridges. A young associate—the one whose voice had been a cautious offering—laid out draft papers. Jax sat with his shoulders rounded to a more honest height. He didn’t look beaten. He looked like a boy who had stayed out too late behind a gym and decided he’d come clean before his mother smelled his jacket.

Edwin took the top packet and read with a murmuring concentration. “Consent order,” he said softly to Lena, “not a judgment. That’s good. We trade noise for clarity.”

The language was clean, a relief like a dish towel fresh from the line: Hollister acknowledged that the 1989 family document did not reflect actual consideration and could not, standing alone, establish ownership of compositions. Hollister agreed to cease any public representations of ownership of Tony Hart’s songs and to retract prior crediting errors on digital platforms “within commercially reasonable time.” Lena, as heir and personal representative of the estate, recognized that termination under 17 U.S.C. § 203 would take effect as to specific grants on dates calculated from the original transfers, and that exploitation before effective dates would continue under existing licenses—provided that accounting and credits were corrected and that all decisions would be made in good faith consultation with the Hart estate. Hollister would deliver the physical masters into escrow at a neutral facility; chain of custody logs would accompany each reel like passports.

There was a paragraph Edwin had insisted on—two sentences that sounded like floor joists under a house: “Nothing herein shall be construed as a waiver of statutory termination rights under Title 17, § 203, which are inalienable. The parties agree to cooperate in relation to registrations with performance rights organizations and standard identifiers, including ISWC for compositions and ISRC for sound recordings, to reflect accurate authorship and control.”

Lena signed where her name asked for her. Jax signed where his name told him to. The associate slid a folder across like a communion plate and said, “We’ll file the consent order with the Chancery Court this afternoon.” She smiled—not the dry professional smile, but the human one that shows you the person behind the binders. “For the record, my dad owns a small bar in Green Hills. Your dad’s songs still live there. He would have liked today.”

Jax cleared his throat. “I brought… uh, these.” He opened a banker’s box as if it might hiss, and lifted out a stack of manila envelopes. He set them in front of Lena without drama. “The session photos. Contact sheets. A couple polaroids Aunt Beth took. I shouldn’t have… you know.” He swallowed. “I know.”

Lena lifted a corner of an envelope and saw her father’s mouth mid‑laugh, eyes closed as if receiving sunlight. “Thank you,” she said. She meant it exactly.

On the ride down, Edwin braced an arm against the elevator wall and exhaled with a hiss. “It’s not the end of law,” he said. “But it’s the end of stupid. Termination notices still run their clocks. Meanwhile, they can’t miscredit a church bulletin without risking contempt.”

“Will Dad’s name go back up?” Lena asked.

“It will,” Edwin said. “And when the reversion dates hit, it won’t just be back up. It will be back home.”

—

Home, for a song, is a funny noun. Sometimes it’s a room. Sometimes it’s a deal. Sometimes it’s a girl at a kitchen table with a machine old enough to vote twice.

Lena took the consent order home the way people take bread home, still warm from a place that smelled like care. She set the folder next to the Revox and the velvet bag with the razor and took out a legal pad to make a list. It was a habit as old as childhood: when the world got bigger, she made columns until it fit a page.

—Correct credits on platforms. (Send clean metadata, include ISRCs.)

—Register unregistered works at ASCAP with proper splits. (Call Mr. Albright, Dad’s old bassist—he deserves his 2% arranging credit on “Carpet of Red Leaves.”)

—Deliver non‑exclusive educational license to East Nashville School of Music. (Draft plain‑language letter: “You may perform and teach these songs, free, forever.”)

—Set up Hart Estate LLC. (Talk to CPA about quarterly withholding from PRO distributions; set aside a student scholarship fund.)

—scan and archive session photos at 600 dpi. (Add IPTC captions: who, where, machines used.)

—Write liner notes that don’t lie.

She wrote each item the way you’d write a promise to a long‑ago friend.

The next day she drove to a climate‑controlled vault on the south edge of town where the firm’s chosen escrow facility kept a better diary than most people do. A man with calm wrists checked serial numbers on each reel case against a spreadsheet that looked like a census. “Revox A77, serial 10517,” he said, almost affectionately, when Lena signed the chain‑of‑custody line for the machine she’d brought to double‑check transfers. He watched her like a person watches a surgeon prepare a family member. “We take the temperature of the air here every hour,” he said. “The tapes will be held like they’re words.”

The room smelled like paper that had decided not to burn.

—

The first digital correction hit platforms a week later around midnight—a line of code changing a line of text changing the shape of a daughter’s breath. Under Ain’t October Forever, the gray attribution box lost its “Presented by” pretension; the composer credit read Tony Hart. A sonically invisible fix, louder than any snare.

Lena had stayed awake on purpose to see it repainted. She refreshed the page and looked up at the Revox, where the VU bulbs glowed their old mild amber like windows in a neighborhood of dark houses. She felt that precise tremble that lives between relief and grief, a harmonic in the chest. She sent a screenshot to Edwin with no words. Edwin replied with a photo of a glass of milk on a saucer and the caption Midnight is for clean changes.

Messages came in like new weather systems. A woman from a hospital cafeteria wrote to say she had played “Last Song” during the mop shift and three men had stood still so long their mops made dry sounds. A high school kid wrote to say he’d listened to the guitar part and realized the slide was a man’s thumb, not a plug‑in; he’d never known thumbs could sing.

Lupe stopped by with pastries and a small gift bag. Inside was a tiny pair of VU‑meter earrings somebody on Etsy had made out of resin and stubbornness. “You’re allowed to wear trophies,” she said.

—

The confrontation people wanted—naked, televised, with a victor’s banner and a villain’s violin—never arrived. Instead there was a city council listening session about small‑venue licensing where Lena and Jax both signed up to speak. The room was fluorescent, the air thick with the sincere breath of people who talk on their feet for a living. Lena spoke quietly about bars that pay blanket licenses and still, through exhaustion or error, forget to file cue sheets; how those missing reports aren’t a scam so much as a slow leak, and how fixing them feeds the people who keep the town’s evenings honest. She mentioned the Mechanical Licensing Collective, the way it had cleaned some messes for digital mechanicals—the dimes and quarters of streams—so that the dollars of performance could feel less lonely. She avoided the word “own.” She said “steward.”

Jax spoke next. He kept his eyes up and his nouns humble. “I messed up credits,” he said into the mic that had heard more sins than pews. “That is not this body’s problem. But it taught me the difference between promotion and preservation. I’m here for the latter. My name is Jax Hollister. I produce sometimes. I also file paperwork now.”

A small laugh rolled through the room like a forgiving wave. People like to see a man carry his own box.

Afterward, in the lobby under a poster for a bluegrass festival, Jax approached Lena with both hands visible like a person arriving at a farmhouse door. “The school sent you a thank‑you?” he asked.

“A crayon guitar,” Lena said. “Best contract I ever got.”

He nodded toward her tote, where a corner of the consent order showed. “I read the part about ISRCs. I used to think those were mystic runes. Now I realize they’re how songs don’t get lost. If you need help registering any of the old tracks you don’t have codes for, I’ll do the boring parts. No credit. Just… penance.”

“Boring parts are the gold,” Lena said. “I’ll send you a spreadsheet.”

They stood awkward for one breath, then the way softened. “There’s a photo of your dad I kept by my desk,” Jax said. “Him putting a razor in a splicing block like it was a baby bird. I wasn’t hoarding it. I was… I don’t know. Afraid it wouldn’t mean as much out of my own sight.”

“Bring it by,” Lena said. “The wall in the kitchen could use a lighthouse.”

—

The request from the East Nashville School of Music came printed in a font that tried and failed to look formal. Dear Miss Lena, it began, and then got to the point with a child’s efficiency: could they perform “Last Song” at their spring recital, and would she, if she wasn’t too busy, come hear it?

Lena went. She sat on a folding chair that had seen more aluminum Christmas trees than explosions and listened while three seventh‑graders, all knees and terror, made something precise. The boy on guitar had a thumb like a prayer; the girl on vocals found the word “fall” and turned it into a hill a person could stand on. They ended with a squeak and a grin and looked at Lena the way people look at bridges.

After the applause turned into chatter, a teacher in a cardigan that had survived many field trips introduced herself and handed Lena a plain envelope. Inside was a certificate with a seal that crinkled under her thumb: Tony Hart Scholarship—Funded by the Hart Estate LLC. The first recipient’s name had three syllables and a future.

Lena drove home in the kind of evening Nashville does best—roadside trees black against a mango sky, windows down, the car filling with the particular smell of someone grilling a pork chop a block away. She did not turn on the radio. The night had its own mix.

—

There remained the question of release. Not of property this time, but of timing: when to make the restored masters breathe in public air; how to sequence the songs so a stranger could walk through them like rooms in a house where somebody loved you and somebody left.

Lupe came over with a stack of vinyl jackets to study and a bottle that made the caps of their ears ring. “Start with the thing that speaks plain,” she said. “Not the cleverest. The honest one.”

“The honest one is ‘Last Song,’” Lena said. “But I don’t want to make grief a marketing plan.”

“It isn’t,” Lupe said. “It’s a compass. You can put a happy banjo right after it so we all remember we’re not saints.”

Edwin, summoned for dessert and clarity, flipped through photos. “This one for the cover,” he said finally. “He’s not looking at us. He’s looking at whatever made him write. Let the title be the fact: Last Song, First Right.” He looked up, eyes soft and proud. “A man’s last song can be a daughter’s first right done right.”

Lena thought of the title like a simple machine: leverage that turns heavy things small.

They built a plan with sticky notes on the wall—track order, release dates spaced like stones across a creek, a short note on Bandcamp that read like a person and not a flyer. Under the plan Lena wrote in small print: Never say: available now on all platforms. She would not talk like an airport. She would talk like a kitchen.

—

The day the vinyl test pressings arrived, the mailman knocked the way people knock on new doors. Lena lifted the lid of the box and inhaled that chemical perfume that says we are about to be real. She set a disc on the Technics and dropped the needle with the care of a woman placing a sleeping child back in a crib.

The first chord came up like a morning. The midrange was a porch. The top end was a clean shirt.

She cried, but not because of loss. Because of presence. The room contained her father and the machine and the woman she had become because she learned where to place her fingers. When the chorus hit, she did something she had promised herself she would do when the day felt worthy: she sang harmony. A small third above, barely there. The kind of harmony that makes people ask later, “Was there wind?”

When the song ended, the house felt taller.

—

Lena did one interview. She did it with the reporter Edwin had cc’d on that first volley, the man who wrote about music like weather—temperatures and pressure systems and the way storms travel in families.

“Why fight?” he asked in the quiet of his small office that had room for a belief and a plant. “Why not let the town remember and let the business boys have their Costco?”

“Because songs are not coupons,” she said. “Because my father signed some bad papers but he wrote good lines. Because the law, when it is sane, says time gives you back what panic made you sell. Because I know how to bake tape and I want my grandchildren to know what truth sounds like when it warms.”

He wrote the story with no villains, only a map back to a house. When he sent the link before it ran, Lena read the last paragraph twice and then forwarded it to Jax with two words: Good weather. Jax replied with one: Agreed.

—

The last show of the summer was not planned. It happened because the Little Room at Belmont had an open night and somebody texted Lena and somebody else found Lupe and soon enough there were fifty chairs and too few cups. Lena rolled the Revox in because it felt wrong not to invite him, and they threaded a tape that had not seen stage light since Bill Clinton was a new story.

People spoke without microphones. They told small truths: the time Tony had given a song away to a kid who couldn’t finish his verse; the night he tuned a guitar to a bent air‑conditioning unit because the room was humid and the A wanted to float. Someone said he’d been a mean drunk and then said he’d become a careful sober, and the room held both like palms.

Lena played Last Song from tape and then, at Lupe’s nod, took the guitar and sang the harmony line she’d practiced. She did not push her voice. She set it where a harmony belongs—beside, below, willing to be mistaken for courage.

When the last note fell into the floorboards, they did not clap right away. They breathed the way people breathe when the surgeon comes out and says it went fine and means it.

In the back, Jax stood with his hands in his pockets and a face that looked like a man hearing a language he finally studied. When people began to move, he approached Lena and held out an envelope. “A receipt,” he said. “For the dollar.”

She tilted her head.

“I found the bill,” he said, almost smiling. “In the old deck from the pitch. It was taped to a PowerPoint like a museum label. I never paid him. I just… showed the idea of paying.” He tapped the envelope. “I donated it to the scholarship fund.” He shrugged. “Consideration that finally considered.”

Lena took the envelope and felt, absurdly, the weight of a lesson become a coin.

“Thank you,” she said. “For showing up like this.”

“I’m learning how to be a consultant,” he said lightly. “You know. Where true.”

They laughed and did not hug. This was not their movie. It was their town.

—

On a Sunday in September, the first check from ASCAP arrived addressed to HART ESTATE LLC, the envelope thick enough to matter. Lena set it on the table next to the razor and the VU‑meter earrings as if populating a small museum and read the remittance detail like a cookbook—where each penny came from, which diner in Paducah had filed its cue sheet, which college radio station had found Side B of a tape that shouldn’t matter and made it a small local moon.

She wrote one check to the scholarship fund and one to Lupe’s non‑profit that paid for string changes in places where people saved up to buy two drinks. She put the rest in a plain account and felt the rare, adult satisfaction of doing right by boring math.

That night she went to the river. The Cumberland moved with its usual patient force, pretending to be quiet. She sat on a bench with a paper cup of coffee and the consent order folded in her pocket like a letter from a sensible friend.

A couple walked by with a dog that looked like a songwriter and the dog stopped obligingly to be admired. The sky darkened to that deep Nashville blue that makes streetlamps admit they are only actors.

Lena took out her phone and scrolled not to her father’s discography but to a recording she had made without telling anyone: the sounds of the studio when nobody is playing. The low breath of the machine room. The faint hum of a transformer. A chair leg’s small complaint. She listened to that for a while and realized it was the sound of enough.

On her way home she stopped by the school to drop off a box of blank CD‑Rs and jewel cases because some kids still wanted to hand people plastic and say “this is me.” The hallways smelled like pencils and hope. On the bulletin board, next to the scholarship certificate and the crayon guitar, was a new photo: Lena at the memorial, hand on the Revox, VU meters bright as kitchen windows. Someone had written under it in purple marker: Trust the meters.

—

The termination effective date for Last Song landed the following spring like a birthday you remembered all year. Edwin came over with lemon bars and a pen that made a nice sound on paper. They signed a new document together—an affirmation more than a contract—acknowledging that control of the composition had reverted to the Hart Estate; that new licenses would begin from this date; that the past had paid what it would pay and the future would pay on time.

“Congratulations,” Edwin said, and meant it like marriage. “You came by your rights the hard way—the only way that holds.”

Lena opened the velvet bag and took out the razor. She did not need to cut anything. She set it on the document like a paperweight.

“What now?” he asked.

She looked at the Revox. The VU meters answered as they always did—quiet, patient, warm. “Now we keep a small room in this city honest,” she said. “Now we answer emails. Now we tune.”

—

In the months that followed, nothing blew up. That was the miracle. Lena taught a class at the community college on audio archiving, a course with a waitlist full of people who had grown up sliding their thumbs across glass but wanted to learn how to polish a capstan. She showed them how to bake and demag, how to label and log, how to love a hiss without worshipping it. She brought in Jax as a guest speaker for the “boring parts” and watched a room full of nineteen‑year‑olds take notes while a man explained ISRCs like a bedtime story that saved lives.

One afternoon in October, the mailman—by now a friend—brought a padded envelope with no return address. Inside was a cassette. The label read in her father’s print: Bedtime—Lena 1996. Her hands trembled before her mind found an explanation: Aunt Beth, cleaning a closet; a neighbor, finding a box; the city still coughing up gifts.

She cleaned the heads on the old Sony deck, pressed Play, and heard a younger house breathe. Her father’s voice came soft, recorded too close, sweet as a man trying to be both storyteller and blanket. He told a fairy tale about a girl with hands that could fix broken clocks. At the end he said, almost a whisper: “If you ever hear this when I’m not near, remember: when the meters bounce easy, you can rest.”

She paused the tape and let the room be a chapel.

—

The last scene did not know it was last. It was just another evening. The oven clicked. The street held its breath before a storm that decided to go north. Lena stood at the kitchen counter, cutting lemons in halves that looked like small suns. The Revox sat where it always sat, a friendly animal. The VU bulbs burned their quiet gold.

She pressed Record. Not because she had to capture anything in particular, but because the act itself was a kind of prayer. She sang a line over the end of “Last Song,” a harmony that tasted like citrus and tea: I put the truth where the chords feel small. She stacked herself once, a whisper on a whisper. She stopped the tape and listened back and it sounded like two women building a place and letting others in.

She poured the lemonade and carried a glass to the porch. The evening smelled like clean rain that changed its mind. Somewhere on Music Row, a kid plugged in a guitar and pledged his future to three chords. Somewhere in Green Hills, a bar back filed a cue sheet and did not know he was saving somebody’s afternoon in March. Somewhere in a little school, a seventh‑grader put her thumb on a string and found a note that would be home all her life.

Lena raised her glass. Not to victory. To stewardship. To machines that tell the truth. To laws that remember people. To the way a daughter can carry a father without dragging him.

Across the room, the VU meters held steady in their small, unwavering suns. They did not flare. They did not demand. They simply glowed, warm as a porch light, long after the door had closed, saying: come in when you’re ready.

She sat there until the ice melted and the night tuned itself to yes.

—

(End.)