When the bell for morning announcements chimed through the beige halls of Jefferson Elementary, Malik Johnson straightened in his seat and told himself a lie: Today would be easy. The lie lasted exactly three minutes, until Ms. Whitmore passed around the laminated handouts that said CAREERS IN GOVERNMENT in blocky blue letters and invited the class to share what their parents did for a living.

He had been ready to talk about his mom. How Tasha Johnson wore a grocery apron and a smile even when her feet ached like hot stones, how she tucked coupons into her wallet the way other moms tucked photographs, how she knew the names of elderly customers and which brand of soup would be on sale next week. He’d been ready to say that his mom held the neighborhood together with tape and grace. But the words that jumped out instead were the ones that would set his day on fire.

“My dad works at the Pentagon,” Malik said. It slipped from him like a truth too heavy to carry in silence.

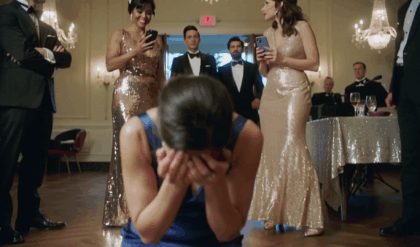

Ten-year-old laughter is sharp and light at the same time. It can sound like birds and break like glass. The room filled with it—Jason Miller’s cackling, Emily Carter’s whisper that was not a whisper, the chorus of chair legs and sneakers as kids shifted to get a better look at the boy they thought was lying again.

Ms. Whitmore tried for neutral and landed on patronizing. “Malik,” she said, tilting her head, as if she could see the truth at just the right angle. “We’re all sharing honestly here.”

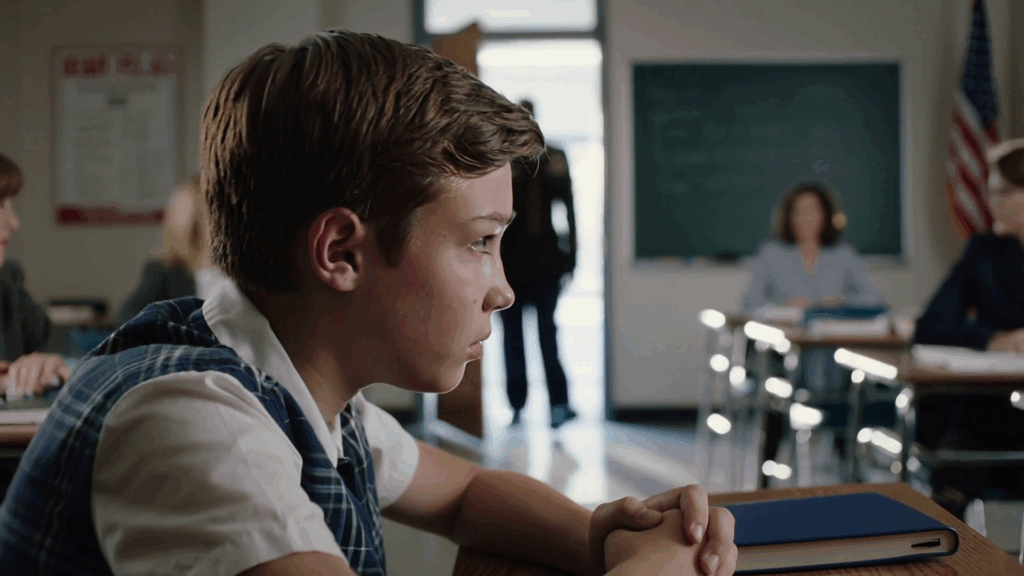

He stared at the map of the United States behind her shoulder—Montana like a broken tooth, Florida like an outstretched leg—and he thought of his father’s boots, the kind that sat by their apartment door, scuffed and honest. “I am sharing honestly,” he said.

Jason made a trumpet shape with his hands. “And my dad’s the President!”

The room broke. Even Aiden, who usually slid Malik a look that said I got you, bro, stayed quiet and small in his seat. Emily said, “No offense, but if your dad worked there, you wouldn’t live off Parkhurst.” She had the kind of face that winced when it realized its own sentences were ugly. She winced.

Ms. Whitmore spread her palms. “Let’s move on,” she said, which was a way of saying let’s move past you.

The lesson moved, the clock moved, the air moved. Malik did not. He folded himself tight behind the plywood of his desk and felt the storm cool from anger into something harder. Truth does not always come dressed for company. Sometimes it arrives in scuffed boots.

Recess carved the day into two clean halves. The sky had the watery blue of a November morning that forgot to be harsh. He walked out under it and tried to join the game of four-square and then didn’t. Jason saluted him like a private to a general. “Reporting for duty, Pentagon Boy!” Kids laughed, then stopped, then laughed again when they realized laughter was safer than thinking.

He stood by the chain-link fence and counted the silver diamonds like a rosary for the god of not-crying. He imagined his father’s hand on his shoulder. He imagined the way his father said his name—slow, like a careful drive through a narrow street.

Ten minutes later, the quiet inside the school office broke first. A secretary stood up so fast her chair rolled backwards. The copy machine whirred to an uncertain halt. A second-grade teacher reached for her lanyard the way a person reaches for a seatbelt in turbulence. A man in dress blues crossed the threshold with the kind of presence that lets a building know it should stand up straighter.

Colonel David Johnson’s uniform caught the light in precise glints—service ribbons like a row of truth pinned to his chest, brass named for metals, not metaphors. He smelled like cold air and laundry starch and the peppermint gum he chewed when he missed cigarettes. He did not stride; he advanced, which is striding with purpose and mercy braided together.

He signed in, because even when you have authority you respect the places that ask for it. The secretary gave him a sticker that said VISITOR in red letters. It looked ridiculous on his jacket. He smiled anyway.

By the time Ms. Whitmore lined the fifth graders outside the classroom door after recess, the colonel’s shadow had reached the far end of the hallway. Ms. Whitmore saw it before she saw him. She turned and her eyebrows climbed her forehead like two careful hikers approaching a cliff.

“Colonel Johnson?” she asked, as if she’d conjured him with her doubt.

“Yes, ma’am,” he said. That “ma’am” knocked a few years of cynicism off her posture. He nodded at the door. “May I?”

He did not wait for the theater of an introduction. He stepped into the fluorescent rectangle of the classroom and found his son as easily as a magnet finds its opposite. Malik stood so fast his chair skittered. The boy’s face ran through three expressions—fear, relief, then something that could have grown up into pride if it had been given time.

“Dad?” Malik said, and it sounded like a question and an answer.

The colonel’s face changed then. A softness, like an off-duty hat, settled over it. He extended a hand and Malik ignored protocol and ran full-speed, which is sometimes the only kind of salute a son knows how to give.

For a moment the fifth-grade classroom was a chapel. The noise of the hallway dimmed. The map behind Ms. Whitmore waited. It felt like a photograph of a family reunion where no one had to perform for the camera.

“I understand you’re talking about government,” the colonel said, releasing his son and turning to the class. “Thought I might stop by. Only had ten minutes.” He smiled when he said it, because in his life ten minutes was the kind of time you learned to make sacred.

Ms. Whitmore stammered a permission she didn’t remember granting. He nodded to her—a small bow of deference—and then he spoke to the children about what it meant to hold a job that most of them saw only on TV. His sentences were plain and full. He used phrases like keep people safe and make good decisions and look out for one another. He did not say war. He did not have to. The creases near his eyes said it for him.

Jason Miller’s hand went up because show-offs have reflexes. “Is it true there are five rings inside the Pentagon?”

“It’s true,” the colonel said. “A through E. Like a target nobody wants to hit.”

“Is the President there?” Emily asked, then blushed. “I mean—not like you would tell us if—”

“The President works down the road,” the colonel said lightly. “Different building. Same weather.”

Aiden didn’t raise his hand; he just asked, “Sir, did Malik tell the truth?” He could have asked the question a hundred ways. He chose the one that made it about honor, not embarrassment.

The colonel glanced down at his son and rested one hand on his shoulder. “He did,” he said. “And if any of you tell a truth that sounds bigger than your life looks, I hope someone gives you the chance to prove it before they decide you’re lying.”

Silence can be a teacher, too. It flickered through the room and left itself behind in the shape of Jason’s lowered eyes and Emily’s bitten lip and Ms. Whitmore’s throat working around the word sorry.

When the colonel left, the air didn’t quite go back to normal. It stayed a little charged, like the time after lightning when you can’t hear thunder anymore but the hairs on your arms still stand up. Word traveled the way word travels in elementary schools—faster than a rumor, slower than a sneeze. By lunch, a third grader in the cafeteria was telling a first grader that the Army had taken over the fifth grade. By gym class, a kindergartner had told a teacher that a soldier had come to rescue somebody.

After school, Malik and his father walked the sidewalk that ran past Parkhurst Apartments and the maple that dropped leaves onto cars like paper messages. The colonel carried his hat under his arm. Without the brim, his face looked ten years younger and a little more tired.

“Thanks for coming,” Malik said.

“You said you had a thing about jobs,” his father replied. “I finished a meeting early.” He glanced down. “How bad was it?”

Malik tried to be brave in the way kids think bravery looks: by shrugging. “They laughed.” He nudged a rock with his sneaker. “It’s fine.”

“Laughter isn’t neutral,” the colonel said. “It’s a tool. Like any tool, it can build or break.” He stopped and turned, which forced Malik to stop and turn too. “Tell me the truth and don’t make a plan for protecting me from it.”

“Jason did the trumpet thing,” Malik said, and gave the soft smile that said see, I can be funny about it. “Emily said we don’t live in the right place.” He didn’t say the part about Aiden being quiet. He didn’t say the part about Ms. Whitmore’s eyebrows.

His father squeezed his shoulder. “I’m sorry,” he said. “I can’t fix the parts of people that want to make themselves bigger by making you smaller. But I can stand next to you while you grow.”

“Mom says taller boys don’t get taller inside unless they work at it,” Malik said.

“Your mom is smarter than me forty percent of the time,” the colonel said.

“Only forty?”

“It used to be thirty,” he said. “I’m learning.”

They reached their building. A neighbor smoked on the stoop and nodded. A siren drew a line somewhere two blocks away. Inside, the stairwell smelled like old floor cleaner and somebody’s dinner. The Johnsons’ apartment held the afternoon light kindly; it made even the secondhand couch look deliberate.

Tasha came out of the small kitchen wiping her hands on a towel, her hair wrapped up in a scarf that looked like summer had decided to be a pattern. She kissed her son’s forehead, then her husband’s cheek, then she stood with her hands on her hips and asked the room if it had behaved.

“Mom,” Malik said without preface, because that’s how you talk to the person who knows your prefaces already, “they laughed.”

Tasha’s face moved in small ways—eye lines deepening, mouth softening, chin lifting. “Mmm,” she said. “Did you tell the truth?”

“Yes.”

“Then let them learn the hard way,” she said. “Truth’s a stubborn mule. It keeps walking.”

The colonel chuckled. “You and your animal metaphors.”

“You and your brass metaphors,” she shot back, and they were smiling again, because love is a muscle and they exercised it daily.

That night Malik opened his homework and found a note from Ms. Whitmore clipped to it with a small paperclip shaped like a star. It said, Malik, if you’re willing, I’d like you to share more about your family this week. Also, would your dad be open to a Q&A for the class on Friday? I apologize for not handling things better today. I’m still learning. —KW.

He brought it to the living room. Tasha read it and made a face like a person who bites into a lemon and finds out it’s sweeter than it looks. “She tried,” she said. “Sometimes trying is the apology.”

The colonel rubbed his jaw. “Friday I could do early,” he said. “I’ll come in civilian clothes. That might be better.”

“Sir,” Malik said, grinning.

“Don’t ‘sir’ me in my own house,” his father said, then winked. “Unless you’re also going to bring me a cup of coffee, Private.”

The week opened like a book with a bent spine. Malik kept reading. He learned algebra you didn’t yet use numbers for and watched a video about the three branches of government that made them look like trees you could climb. He didn’t breathe easier, exactly, but he breathed truer. Jason and Emily were awkward in the way kids are awkward when adult-sized regret starts growing in their chests. Aiden went back to sliding Malik a look that said I got you, bro.

On Wednesday, Ms. Whitmore asked the class to write a single page titled Where I’m From. Emily said, “Do we say street names?” and Ms. Whitmore said, “Only if the street feels like a character in your life.”

Malik wrote about a hallway with scuffed baseboards and the smell of onions when his mom cooked for the church food drive. He wrote about the Potomac River that glinted like a blade on good days and a bruise on others. He wrote about boots by a door and a hat on a table and how service could look like carrying groceries upstairs for Mrs. Hernandez when the elevator broke. He wrote the word Pentagon once and then crossed it out and then wrote it again, slower, as if the letters themselves needed to be steady.

Ms. Whitmore knelt by his desk while he wrote and did not speak. Teachers who have been wrong try to be right in little ways. Silence can be one of them.

At the end of the day, Emily approached him by the cubbies. She held her paper like a flag of truce. “My mom’s a nurse,” she said. “She always smells like hand sanitizer and peppermint gum.” She shifted her weight. “I shouldn’t have said the thing about the neighborhood.”

He nodded. “Okay,” he said, which was forgiveness without ceremony.

Friday the colonel wore a dark suit and a Navy-blue tie that Tasha had bought at Ross for $9.99. His shoes were polished but not new. He stood at the front of the classroom and leaned on the back of a chair and answered questions that ranged from serious to ridiculous.

“Do you know any secrets?” Jason asked.

“I know where Ms. Whitmore keeps the extra pencils,” the colonel said gravely. The class laughed, and the laughter built instead of breaking.

“Are you ever scared?” Aiden asked.

“Yes,” the colonel said, and let the quiet sit down next to that small, plain word. “Being scared and being brave are not opposites. They hold hands.”

After Q&A, he handed Ms. Whitmore a folded packet. “This is something I give new analysts,” he said. “It’s about good questions and better listening. Maybe it works in fifth grade.” She looked at it like a person looking at a mirror they hadn’t asked for, and then she said, “Thank you,” in a voice with less bark in it.

That afternoon, Ms. Whitmore announced the class would visit the Pentagon Memorial the next week as part of Veterans Day learning. “We won’t be going inside the building,” she said. “But we’ll talk about the people who worked there and the families connected to them.” Her eyes flicked to Malik, then away.

Malik told his parents over dinner. Tasha stirred the pot on the stove and said a soft prayer for bus safety and for children not to run near roads. The colonel said he’d try to meet them there if his schedule allowed. Malik imagined the benches others had described—stone that held names like steady hands, angled toward the building for those lost inside and toward the sky for those who had been on the plane. He wondered what it would feel like to read a name he didn’t know and care anyway.

The morning of the field trip had the stripped-down beauty of late fall—a sky so high it looked like it forgot how to lie. The bus smelled like vinyl and old conversations. Malik sat with Aiden. Jason flicked spitballs into his own backpack because he didn’t know what else to do with his energy.

At the Memorial, the class moved in a line like a slow river. The benches were sleek and low, each with water running gently beneath. Ms. Whitmore read a plaque aloud. A woman in a park ranger uniform spoke about how the Memorial arranged its names by age, the youngest to the oldest, which made the space feel like a family table where elders and toddlers could sit side by side.

Malik felt his father before he saw him. Presence is not always about sound. The colonel stepped into the garden quietly, his suit a softer kind of armor. Ms. Whitmore looked relieved in a way that felt like she was borrowing some of his steadiness just by standing near it.

“This place is about memory,” he told the cluster of fifth graders who were trying to be respectful and were also still fifth graders. “Not just of what happened, but of who people were in their ordinary days.” He pointed to a bench with a name and told them how she had been a secretary who always brought extra granola bars to work in case a coworker missed breakfast, and how someone remembered that and told it, and how that telling became a kind of monument you carry inside you.

Emily’s hand was half-raised, half-hesitant. “Do you come here a lot, sir?”

“Not as much as some,” he said. “Enough.” He swallowed. “When you work in a place long enough, you realize buildings are only the bones. People are the muscle.”

They stood together in a shared quiet that wasn’t heavy. The wind picked up and slid through the trees like fingers through piano keys.

On the bus back, Jason sat across the aisle and didn’t make a joke. “That was…cool,” he said, and then corrected himself. “Not cool. Important.” He faced the window so he wouldn’t have to see how Malik took the gift of that sentence.

If life were a straight line, that might have been the end of the lesson. But life, like the Pentagon, is a series of rings. You move in and out of them. You meet the same doors twice.

Two Tuesdays later, at a strip mall that made every store look related, a security guard stopped Malik by the automatic doors of a sporting goods store. The teenager with the earpiece said, “Empty your pockets,” and he said it like please would turn him into a different person. Malik’s mouth went dry in the instant way mouths do when they realize there is a stranger in the room and the stranger is danger.

“I didn’t take anything,” Malik said. His pockets held lint and a Lego head and the folded money his mom had given him for socks. He had tried on a baseball cap and then put it back.

A woman—white, forty, ponytail—watched from the register. She assumed her eyes were telling the truth because eyes are loud.

A hand touched Malik’s elbow. Not the guard’s. Ms. Whitmore’s. She had been in the parking lot buying holiday lights; she had seen the guard tail him from the end of the aisle. Her voice was quiet but made of steel cable. “He’s my student,” she said. “If you suspect him, call his mother and tell her you did, in front of me.”

The guard’s mouth pursed. “Ma’am, I—”

“You what?” she asked. Not loudly. Just precisely. “You saw a kid with brown skin and decided merchandise sticks to him?”

He didn’t apologize. People who lead with authority don’t always know where the brakes are. But he stepped back. Malik let out a breath shaped like a sob and a laugh tangled together. Ms. Whitmore did not touch him again. Instead, she walked him outside and sat him on the curb, where the afternoon light made everything look equal and impartial for a few minutes.

“Do you want me to call your folks?” she asked.

“I can call,” he said. His hands shook, so she dialed and then handed him the phone. Tasha arrived with the kind of speed that turns a mother from a person into a plan. She hugged him and then straightened and looked the guard in the eyes and gave him a sentence he would hear again in the quiet hours. “You are going to be better than this.”

That night Ms. Whitmore wrote an email to the principal that began with the words Today I failed to protect my student and ended with a plan to invite a community officer to talk about rights and respect in public spaces. She did not center herself in the apology. Growth, when it is real, is quieter than we expect.

At school the next week, Malik noticed Jason and Emily moving differently around him. Not careful, exactly—careful can be clumsy. Aware. He noticed Aiden standing closer. He noticed Ms. Whitmore listening more. The room felt like a place whose furniture had been rearranged to make more space for the truth to sit down.

December rolled in with its catalog of holidays and its insistence that everyone remember to be both merry and kind. The fifth-grade class hosted a toy drive. Tasha brought three extra sets of mittens because she said kids deserved warm hands more than toys sometimes. The colonel showed up in a sweater with a reindeer that Malik pretended to hate and then secretly loved because it made other dads look softer and his dad look human.

In January, Ms. Whitmore announced the regional robotics competition and said, “I want a team from our class.” Her eyes slid to Malik. He looked away on purpose so she’d have to see him not as a caricature of the kid whose dad worked somewhere impressive but as the kid whose hands built careful things. He had always liked seeing how moving parts could learn to hold each other.

They formed a team: Malik, Aiden, Emily, and—because life insists on making art out of imperfect materials—Jason. They met at the library after school. Tasha brought snacks that didn’t crinkle too loud. The colonel sat in the back sometimes and graded reports in the way that meant he crossed out his own words and wrote sharper ones.

The first time their robot pivoted without falling apart, they cheered like sports fans. The second time, they didn’t cheer; they got quiet and watched in reverent awe the way you watch a baby take a step. The third time, it failed in a different way, and they learned to love that too, because progress is polite enough to introduce you to its cousins, Error and Try Again.

At the regional competition—held in a newer high school that smelled like fresh paint and anxiety—they found out other teams had money that looked like confidence. Their bot’s frame had a wobble to it, like a person who danced better when nobody watched.

Jason cracked his knuckles. “We can’t win,” he said, which was his way of saying he was scared he’d fail publicly.

“Winning’s not the only sentence,” Malik said. “Sometimes the verb is build.”

They made it to the semifinals. When their robot stalled in a corner and refused to interpret commands like anything other than a dare to nap, Malik did not kick it. He crouched and adjusted a wire with nimble fingers and whispered, “Do the thing you were made for,” and for a hilarious second he thought he was talking to himself.

They lost by two points. It felt like a place you could live if you let yourself: close enough to imagine a different outcome, far enough to keep you honest. On the bus back, Emily rested her head on his shoulder for a second and then pretended she hadn’t. Jason said, “I like you, man,” and then pretended he hadn’t. Aiden said nothing and chewed his gum like it was an oath.

That night the colonel knocked on Malik’s door and sat on the edge of the bed like he had when Malik was small and the monsters in the closet were louder. “Proud of you,” he said.

“We lost,” Malik said.

“I didn’t say I was proud of the scoreboard,” his father replied. “I said I was proud of you.” He paused. “Also, for the record, that mid-match wire adjustment was the kind of problem-solving we pay people six figures for.”

“Six figures?” Malik said, and then grinned. “Like, $100,000?”

“Like, some numbers that matter less than the work does,” the colonel said. “But yeah.”

Late winter sharpened the air. The ice on the apartment steps turned walking into a careful act of faith. The colonel left earlier and came home later. Tasha kept soup warm on the stove. Malik learned a new thing about time: you can be inside it and miss it at once.

One Thursday evening, when the sky was already halfway to night, a call came. The colonel listened, answered with clipped yeses, and looked at his son in the gap between sentences with a softness that owed something to guilt. When he hung up, he sat down before he spoke.

“I might be gone a bit,” he said. “Temporary assignment. Stateside. Just longer days, different base. I’ll be around, but I’ll be…less around.”

“Okay,” Malik said. He swallowed. “Is it dangerous?”

“It’s always important,” his father said, which was not an answer and exactly the answer. “Your mother will be mad at me for not asking you to take out the trash right now.”

“I already did,” Malik said.

“See?” the colonel said. “You’re running this house.”

He was gone more after that. Not gone-gone. Not the kind of gone that breaks calendars. But enough that Malik found himself cataloging the sounds that meant Dad: the espresso machine sputtering in the morning, the low whistle of a tune he never fully finished, the weight of boots by the door. When those sounds were missing, the apartment felt like a room that could echo if you breathed wrong.

On a Sunday, Tasha took Malik into the city on the Metro because she said when you live near the capital you should act like it belongs to you too. They stood on the Mall and looked at the long reflecting pool that made the Washington Monument look like a trick done with mirrors. They ate hot dogs that tasted better than they had a right to. They stood inside the Air and Space Museum and tilted their heads back to see the planes that had retired to the ceiling. Malik imagined his robot up there, floating in a room that kept memories the way careful hands keep glass.

They walked past a group of protestors holding signs about a war that had turned into wordless numbers on the news. Tasha squeezed his hand. “Every sign represents a person,” she said. “Including you.”

That night, the colonel came home early and found them asleep on the couch, the TV murmuring about weather. He stood in the doorway and let his face forget how to be official. He kissed Tasha’s hair and then brushed a curl off Malik’s forehead, and in that private act he looked more like a hero than he ever did in uniform.

Spring widened the days. The fifth graders began talking about middle school with the excitement of people who think they are about to be reborn. Ms. Whitmore grew better at being the kind of teacher kids remember for the right reasons. She instituted reading circles that let kids choose titles that looked like their lives. She corrected herself in front of the class when she made assumptions. She said the sentence I was wrong out loud twice and did not melt.

One afternoon she asked Malik if he would read his Where I’m From piece at the school assembly. He said no and then yes and then no and then yes again. When the day arrived, he stood on a stage that had seen its share of talent shows and nervous Christmas pageants. The microphone smelled like nervous breath. He unfolded his page and let the paper shake. He read about boots and doors and soup and rivers and truth and how it lives in small acts.

When he finished, there was a quiet moment that felt like a house waiting for the furnace to kick back on. Then the room warmed with applause, not thunderous but real.

Afterward, a parent approached Tasha and said, “Your son speaks beautifully,” and Tasha said, “He has a good editor at home,” and chuckled, and the woman smiled and did not know until later that the editor was a man who wore a suit like armor and took it off every night in a small apartment.

At the end of May, the colonel surprised Malik with a badge that said BRING YOUR CHILD TO WORK DAY. “It’s not really called that,” he said. “But someone decided we should remember we’re parents before we’re anything else, and I signed up like I was getting the last spot in line.”

They passed through security that made airports look like suggestion boxes. They walked corridors named by letters and punctuated by history on the walls—photographs of faces that had aged into stories, maps that tracked conflict like storms. The colonel nodded at colleagues who straightened instinctively when they saw him.

“This is where I spend my days,” he said. “Which means it’s where our family spends them too, whether we like it or not.”

In a small conference room with a window that framed the Potomac like a painting, the colonel introduced Malik to a woman named Dr. Nguyen who said words like cybersecurity and resilience in a way that made them sound like puzzles you could actually solve if you gave them time and respect. “We need minds like yours,” she told Malik, who didn’t think his mind had a category yet and was startled to find it did.

They ended at the Memorial again. The colonel stood with his son and read names in silence. Then he said, “There are some truths we say out loud and some we carry like water so that other people can drink.”

“Was I wrong to tell the class?” Malik asked. The question had slept under his tongue for months.

“No,” his father said. “You were wronged. Different thing.” He put an arm around his son’s shoulders. “Truth doesn’t need permission. It asks for courage.”

The last week of school arrived with its exhaustion and its wildness. Kids wrote in yearbooks with the kind of dramatic promises only fifth graders can make and expect to be kept forever. The gym turned into a stage for awards that came in the shape of paper and the weight of pride.

Malik won the Citizenship Award, a rectangle that said he made the room better. Jason got Most Improved in Math and grinned like someone had finally pronounced his name correctly. Emily took home a ribbon for Writing and gave Malik a look that said You made me brave on paper. Aiden didn’t get an award and pretended not to care, and then Malik pressed his own paper into his friend’s hands and said, “I want you to hold this for me. It’ll look good in your room,” and Aiden blinked away something that wasn’t tears and said, “Okay, but I’m giving it back in September.”

After the ceremony, Ms. Whitmore found the Johnson family in the hallway and said, “Thank you for trusting me to grow.” Tasha shook her hand and said, “Keep going.” The colonel nodded and said, “We all are.”

They walked out into a sunlight that felt like a graduation of its own. On the sidewalk, the colonel knelt—boots creaking, suit folding—and looked his son in the eyes. “Middle school will test you in new ways,” he said. “People will test you. Do not audition for parts in their stories that require you to be small.”

“I won’t,” Malik said. He wasn’t promising perfection. He was promising a posture.

A car horn sounded. Mrs. Hernandez waved from across the street. Kids shouted goodbyes that sounded like hellos.

“Dad,” Malik said. “When I said the thing that day—about where you work—I think I wanted people to see me different. Not better,” he added quickly. “Just…true.”

The colonel smiled. Lines fanned from the corners of his eyes like roads on a map. “They do now,” he said. “Because you kept showing up as yourself.” He stood and ruffled Malik’s hair. “Also because I showed up in enough brass to blind a bat.”

They laughed. The hallway where it had started seemed very far away and very close at the same time.

On the last evening of June, when the air tasted like cut grass and fireworks-in-waiting, Jason and Emily knocked on Malik’s door with two cups of melting ice and a battered deck of cards. They played on the stoop, arguing about the rules like siblings do. At some point Jason said, “I was a jerk,” and Malik said, “Sometimes the first draft is a jerk,” and they all three laughed too hard at that because relief turns small jokes into big ones.

A breeze moved down the street and lifted the corner of the flag on the apartment building like a salute. The colonel watched from the window and finished an email and closed his laptop and decided to make popcorn because children should taste joy that is warm and buttery and uncomplicated whenever possible.

Later that summer, the robotics team met once a week to mess with circuits and make mistakes on purpose. Ms. Whitmore—now Karen in texts to parents—stopped by with iced tea and clumsy enthusiasm. She brought a guest speaker who had grown up ten blocks away and now worked in town doing something with satellites that she described as “keeping the sky honest.”

“Do you ever get tired of making people safe?” Malik asked her after, surprising himself with the shape of the question.

She considered. “I get tired,” she said. “I don’t get tired of the why.”

He nodded. He thought of the Memorial and of boots and of a grocery apron and of a classroom that had learned to sing a different song. He thought that maybe the world was exactly as complicated as everyone kept saying, and also simpler than we allow: tell the truth, carry it kindly, make room for other people’s truths to sit down next to yours.

On a crisp September morning a year later, when the memory of the field trip had softened into story, Malik walked into his first middle school social studies class and a kid at the next table said, “You’re the Pentagon kid, right?” and he exhaled and smiled and said, “I’m Malik,” and the kid said, “Cool,” and then borrowed a pencil without asking and then immediately said, “Sorry,” and Malik laughed and said, “It’s fine,” and they started on their map work like none of the old ghosts needed feeding anymore.

He did not erase the part of himself that had wanted to be believed. He kept it. He let it teach him to make room for the messy ways people say who they are. He carried the sentence Truth doesn’t need anyone’s approval. It stands on its own the way other kids carried lucky coins or a secret crush. He learned that sometimes the most honest thing you can do is keep showing up where you said you would, in boots or sneakers or socks.

On the anniversary of the field trip, he took a bus by himself to the Memorial. He sat on a bench and put his palm flat on the cool surface and imagined the lives beneath the names. He whispered hello like a promise. When he stood to go, he found his father on the path, hands in pockets, tie loosened, shoulders a little lower than they used to be.

“You beat me here,” the colonel said.

“I had a feeling,” Malik said.

They walked together, slow, as if the path had a speed limit posted in respect. They didn’t speak for a while. They didn’t need to. The truth walked with them. It was not loud. It did not try to be impressive. It did not ask for permission. It kept walking.