“Get out! And don’t you ever come back!”

The shout cracked through the aisle like a snapped broom handle. Bottles rattled; a teenage cashier flinched. October wind shouldered the narrow doorway of Reynolds Market and swept the smell of bleach and cheap lemons into the street. A girl in a thin, pilled jacket staggered as the manager’s hand fell away from her wrist. A cardboard box of single‑serve milk crumpled underfoot, its corner bursting, white arcs spattering the gray sidewalk.

Emily Carter was ten years old and had learned the particular shame of being looked at as if you were an error. She pulled the jacket tighter, more habit than warmth, and kept her chin up the way her mother used to tell her to do. The milk bled toward the gutter in a bright trickle. People passing didn’t stop. A bus sighed at the curb and lurched away.

“That’ll teach you,” the manager said from the doorway. He was stout, fiftyish, with a jaw that always seemed to be biting down on something invisible. His nametag read REYNOLDS as if it were a sentence. “Stealing’s stealing.”

Emily said nothing. She could feel her heartbeat in her teeth. She had pictured slipping the carton under her jacket and walking out without being seen. She had pictured pouring it into chipped bowls at home, Liam’s lashes unsticking from his cheeks, Sophie licking the mustache away with a pink tongue, the three of them giggling in that small way they still could. She had not pictured this.

A man in a charcoal suit had paused on the sidewalk the way people pause when something crosses old weather in them. He was tall, late thirties, clean‑shaven, a coat over his arm though the cold didn’t seem to reach him. He saw the milk, the child, the way the manager’s mouth made a hard line of judgment and certainty. He saw the newness of the jacket’s pilling and the oldness of the shoes.

“Is she all right?” he asked quietly.

“Mind your business,” Mr. Reynolds snapped. “We’re not a charity.”

The man didn’t look at Reynolds. He crouched to Emily’s height, careful not to crowd her. “Hey,” he said, voice low and steady. “You OK?”

Emily nodded, then shook her head. Her eyes were swollen from trying not to cry. “I wasn’t gonna—” She swallowed. “It was for my brother and sister.”

The man’s name was Michael Harrington, and there was a version of him that existed in glossy profiles: self‑made, logistics king, investor with a talent for putting people in the same place as possibility. That version of him never talked about the nights his mother skipped dinner and told him she’d eaten at work, or about how it felt to sleep under two coats because the furnace had given up in January. He had a good memory for certain kinds of cold.

Michael stood, pulled his wallet, and held out a hundred‑dollar bill. “For the milk,” he said to Reynolds. His tone asked for nothing.

Reynolds hesitated, pride and policy wrestling behind his eyes. He took the bill anyway. “Keep her out of my store,” he muttered.

Michael picked up the burst carton with two fingers, the way you pick up a hurt thing. He looked back to Emily. “Come on,” he said gently. “Let’s get you warm.”

He walked half a block to a little café with fogged windows and a bell that rang like a spoon against a jar. The barista looked at the girl and at the milk on Michael’s cuff and said nothing except, “Kitchen’s still doing breakfast.” They sat in a booth that had a rip in the vinyl patched with duct tape. Michael ordered hot chocolate, grilled cheese, two bowls of chicken noodle soup, and a full half‑gallon of milk.

Emily’s fingers shook around the hot chocolate and then steadied. Steam made her lashes bead. Michael waited while she ate too fast at first, a deep animal rush easing into something like relief. When she finally stopped to breathe, he asked, “What are your names?”

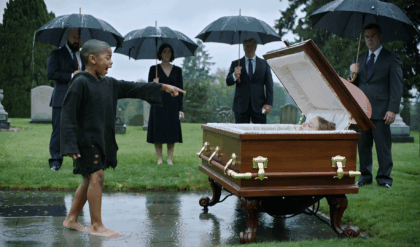

“Emily,” she said. “My brother’s Liam. He’s six. Sophie’s four.” She looked at the half‑gallon like it was an animal she was afraid might bolt. “Our mom died. My dad—” She pressed her lips together. “He works sometimes.”

“Where do you live?”

“In an apartment off Haddon. Third floor. The heat—” She shrugged. “Sometimes.”

Michael nodded like this matched something in his head. “I’m Michael,” he said. “Can I walk you home? I’ll carry the milk.”

Back outside, the cold had sharpened. The sky had that Chicago color like the underside of a spoon. They moved past a pawn shop with its window full of guitars that never got played, past a church with a letterboard that said LOVE IS A VERB, past a deli that smelled like onion and hope.

Emily led him into a brick building where the stairwell smelled of damp and someone’s boiled dinner. The third‑floor hallway had a missing lightbulb. The door to 3C was peeling at the corners like a Band‑Aid. Inside, two small faces turned toward the air when the lock gave way.

“Em!” Liam said, and then his eyes went to the bag in Michael’s hand. He checked himself, a small man trying to be gracious. “Hi.”

Sophie didn’t speak. She climbed to her feet from a nest of thrift‑store blankets and drifted toward the bag with a gravity stronger than shyness.

“This is my friend Michael,” Emily said. The word friend surprised her as it came out. She didn’t know what else to call someone who looked at you without making you small.

Michael set the food on the counter and poured three glasses of milk. He found bowls and ladled soup. The apartment was a tight rectangle of patched linoleum and secondhand furniture. A framed photo sat on the bookshelf: a young woman with the same eyes as Emily, laughter inside her mouth.

Michael looked at it and then away. “I don’t want to intrude,” he said, which is what you say when what you really mean is: I wish I could build a wall between you and the wind.

There was a key in the lock and the door opened to a man with four days of stubble and the smell of a shift that had run out of hours. He took in the scene, the stranger in the kitchen, and bristled.

“Who are you?” he asked, not unkindly—just someone who had been surprised too often to react with grace.

“Michael Harrington.” He offered a hand. “I ran into Emily.”

The man’s eyes went to the milk, to the soup, to Emily’s posture—a mix of alarm and apology. “Daniel Carter,” he said at last. “I’m their dad.”

Michael nodded. “You working today?”

“Supposed to be.” Daniel rubbed his forehead. Grease had worked itself into the knuckles. “Got sent home. Hours cut.” He glanced at the photo on the shelf as if checking that it was still there. “I don’t—We’re fine. We don’t need—”

Emily’s chair squeaked. “Dad,” she said, a warning and a plea in one syllable.

“We needed help when I was a kid,” Michael said, with a calm that didn’t feel like pity. “Someone helped us.” He reached into his coat and pulled out a business card with an address on Kinzie and a phone number that answered twenty‑four hours a day. “I can arrange some things. Food. Heat. A few repairs. And I know a counselor who works with families. Nothing strings attached. Nothing that takes your kids away. You’ve got my word.”

Daniel looked at his daughter, at the bowls in front of his children, at the space in his chest where a good father was supposed to live quietly and with certainty. Shame rose and then receded, like a tide that knew it couldn’t keep coming if people were to breathe. “I don’t want them taken,” he said.

“I won’t let that happen because you asked for help,” Michael said. “We go forward from the truth, not from fear.”

He left his number on the counter and his apology for intruding on the air, and when he stepped into the hallway his jaw was tight the way it got when he was making a decision.

Michael owned trucks—hundreds of them—and knew how to move what was needed from where it sat to where it could change a day. By nightfall, a space heater with modern wiring arrived, then two more so the children wouldn’t have to drag theirs between rooms like a campfire. A property manager named Pike, who had avoided calls all week, found himself answering this one. The boiler had a part that “would take time,” Pike said.

“You have until tomorrow,” Michael said. “Or the city will have the week.”

He called Andrea Morales, a social worker who’d once taught him the phrase trauma‑informed not like jargon but like a map. Andrea did not arrive with a clipboard and a threat. She arrived with a tote of groceries, a library card application, and eyes that met kids where they were without asking them to come higher.

By the end of the second day, the heat was working and Liam had a doctor’s appointment for the cough that had become background noise, and Sophie had a winter coat that zipped all the way up. Andrea sat across from Daniel at the little table with the wood showing through the veneer and spoke about grief as if it were a weather system you could learn to read. Daniel’s mouth trembled at the edges. He nodded yes.

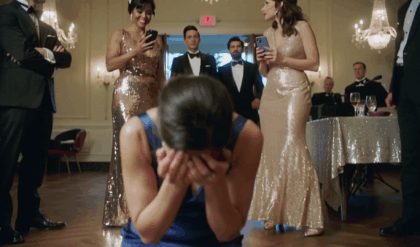

On the third day a grainy cell phone video appeared online: a little girl being pulled by the wrist through a store, a man in a wool coat stepping between them, spilled milk making a comet’s tail on the concrete. Someone had filmed it from the bus. By evening it had a million views and the comments had divided into armies. There were people who wanted to burn the store down and people who wanted the father arrested and people who wanted to tell their own stories of being ten in a world that has rules for even the hungry.

Michael called his publicist, who had built a career discouraging him from doing things like this. “Say nothing,” she advised.

He said something.

He stood in front of a brick wall he’d slept behind once as a boy and recorded a video on his phone. “My name is Michael Harrington. Some of you have seen footage of a little girl at a grocery store. I met her. Her name is Emily, and she is brave. She took milk because her siblings were hungry. That tells me about her courage and our failure. If you’re about to write something cruel about her father, please don’t. If you’re about to boycott a store, consider donating to your nearest food pantry instead. Emily and her family are OK today. Let’s make sure more families are OK tomorrow.” He linked three pantries and two shelters and said the name of his mother out loud, because he wanted to feel the way it anchored him when the wind rose.

The comments shifted. Not all of them—nothing ever moves all at once—but a little, the way a crowd at a parade shifts when a marching band hits the right note.

Andrea asked permission to bring a teacher by. “Someone who sees kids,” she said. “She’s good with words. Bolts chairs to the floor when the world is sliding.”

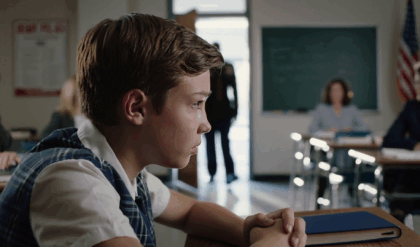

Ms. Jennings came with a leather tote that had pen ink freckles. She sat on the carpet with Sophie and drew a lamp and a cat and a house where the roof wasn’t gray. She asked Emily about school, and Emily told her a version of the truth—the softer one you tell grown‑ups who know how much you’re leaving out. Ms. Jennings asked if Emily liked to write.

“I used to,” Emily said. “Before.”

“Maybe ‘before’ can be a place you visit and not a place you live,” Ms. Jennings said. “Sometimes words are the way across.”

Emily didn’t know about words being bridges yet. But she knew how to carry Liam on her hip when the elevator was broken and Sophie to the bathroom when the hall light went out. She could learn this too.

Two weeks later, Emily read a paragraph in class about the sound of heat coming back to life, how it knocked like a visitor who means well but forgets their key. Ms. Jennings looked at her with the kind of pride you can live on for a month.

Michael came on Wednesdays after work, always calling first, always asking what was needed before he decided what to do. He discovered that Sophie liked puzzles and that Liam could take apart anything and put it back together with two screws left over—and that this was not failure but an engineering mystery he would one day solve. He discovered that Daniel, when he laughed, sounded like a man who hadn’t yet decided to give up on himself.

Daniel tried counseling. He didn’t like the first therapist and said so. He liked the second one, a man who wore cardigans and called grief a wild animal you could make eye contact with if you had to. Daniel began to lay off the cheap whiskey that took the edge off at night and left a knife behind in the morning. He started sleeping at regular hours. He started showing up at a mechanic’s shop on 26th Street where a man named Arturo needed someone to hold a flashlight and not talk too much.

Not everything got better in a straight line. On a Thursday in November, Daniel didn’t come home. Emily watched the clock until the numbers began to feel like an enemy. When the door finally opened after midnight, the air that came with him smelled like a bar and the inside of an old story. He saw Emily’s face and nearly closed the door again to keep his shame outside.

Michael arrived without judgment and sat Daniel down at the table where grief had learned to use its inside voice. Andrea came too. They talked about relapse the way you talk about weather: something that happens to people, something you plan around, something you respect because it has power. Daniel pressed his palms flat to the table and asked what made a good father, and Michael said, “You keep coming back.”

The first snow came early. The city shifted into muffler mode. The kids learned to stamp their boots on the mat and not to touch the radiator with bare fingers. Liam’s cough left. Sophie slept with both arms over her head like a startled starfish. Emily learned how to cook scrambled eggs the way a neighbor down the hall had shown her—slow, with patience and butter.

On Thanksgiving, Michael asked whether they would like to come to his place. He lived in a condo that looked like a magazine had come to life and then decided to be kind anyway. He cooked—he had learned from his mother, who could make a roast out of a cheap cut and love. He burned the rolls and laughed and ordered a backup pie from the bakery downstairs. Daniel brought cranberry sauce in a can because he insisted on bringing something, and Sophie discovered that the sound a can makes when it releases is the funniest sound in the world.

At the table, Michael told a story about a woman named Patricia who once hid money in a flour tin so her boys wouldn’t spend it on baseball cards. Daniel told a story about the first car he ever fixed, and how you can tell when a thing wants to live because it sounds different. Emily didn’t tell a story. She listened to the way adults sounded when they weren’t lying to her for her own good.

Later, when they were clearing plates, Emily bumped a glass of milk and sent it across the table in a smooth white mile. She froze. Somewhere deep in her body, a memory stood up and took a breath.

Michael didn’t flinch. He put a towel down and sopped it up and said, “When I was nine, I spilled a whole gallon on my mom’s new rug. We both cried, and then we both laughed. The rug survived.”

Emily laughed without meaning to, a sound like the top of a soda can when it first opens.

In December, a different kind of attention found them. A man in a beanie with a camera knocked and asked to tell “the story.” Michael said no for them, and then asked them if they wanted him to keep saying no. Emily said she didn’t want to be on TV for stealing. Liam asked if the camera could make him look like Spider‑Man. Sophie hid behind the couch and said the word no in a way that meant she wasn’t used to being given the option.

Michael put together a plan he wished someone had put together for him when he was small: private help first, public praise last. He opened a small family fund in Daniel’s name with a lawyer named Lisa Grant who wore boots that meant business and told them what words like guardian and trust meant without making them feel like they were learning a language that wasn’t theirs.

“Sometimes people will try to buy your story,” Lisa said. “You don’t owe anyone anything. You can accept help and keep your dignity. Those things aren’t opposites.”

One afternoon, Mr. Reynolds came up the stairs and stood in the hallway like a man outside a confessional. He had a paper bag in his hand and the look of someone who had been told about himself by strangers for a month.

“I came to say I’m sorry,” he said to Emily when she opened the door a careful two inches. “I got it wrong.” He swallowed. “I thought the rules were the only way to keep a store alive. I forgot they’re for keeping people alive.”

He held out the bag. Inside were three boxes of shelf‑stable milk, two boxes of cereal, and a small envelope. “Don’t need to take it,” he added. “Just—wanted to say I saw the video. That man, he’s right. I don’t need a boycott. I need to be better.”

Emily didn’t know how to accept an apology from an adult who had made her feel small. She looked at Michael.

“It’s your call,” Michael said. “If you want to close the door, I’ll stand here while you do.”

Emily took the bag. “Thank you,” she said, because her mother had taught her that thank you wasn’t surrender, it was acknowledgment. Reynolds’s eyes got wet. He wiped them with the side of his hand as if he were embarrassed to have overflow.

“I could use a hand stocking on weekends,” Reynolds said, not sure who he was talking to, exactly. “If you ever want a legit shift. Pay is lousy but honest.”

Daniel nodded from the doorway. “I’ll come by,” he said. “I’ve been out of work.”

Reynolds blinked. “You a mechanic?”

“Yeah.”

“My delivery van’s been making a noise like a squirrel with a grudge. You mind taking a look?”

In January the van made the right sounds again, and Daniel started picking up hours. Not enough, but more than the nothing that had begun to feel like a place you lived. He kept going to counseling. He went to a meeting in a church basement where coffee tasted like penance and men told the truth without making speeches about it. He started eating breakfast with his kids while the light came in sideways.

Winter did what it does and then, eventually, remembered how to end. On the first day the lake smelled faintly like wet iron instead of ice, Emily walked home from school with a flyer in her backpack for a writing contest. The prompt was HOME IS… and the prize was a gift card to a bookstore that looked like magic on the outside and passwords on the inside. Emily started writing on the bus and didn’t stop until the elevator hiccuped and brought her to the third floor.

Home is the way a radiator clanks like it’s apologizing for being late. Home is a picture on a shelf that you say goodnight to even when nobody asks who you’re talking to. Home is milk in a glass and nobody yelling.

She showed it to Ms. Jennings, who read it twice and then once more, slower. “This is yours,” she said. “I mean that both ways. You wrote it, and it belongs to you.”

Emily won second place and bought a used copy of a book about a girl detective who always took notes even when nobody believed her. She began to keep a notebook that fit in her pocket.

In March, an inspector from the city came through the building with a clipboard and a face like he had chosen this job on purpose. He wrote citations for things the tenants had stopped noticing—loose handrails, flaking paint, a smell in the basement like the past refusing to leave. Pike scowled and said phrases like excessive and unnecessary and do you know how much that costs. Michael called him and said a different phrase: how much does it cost to move out.

By April, the Carters moved into a two‑bedroom on a block with more trees and fewer sirens. The rent was subsidized by a fund in Daniel’s name that Lisa had structured to avoid making him feel like a guest in someone else’s life. Emily got the window that faced east. Liam got bunk beds he took apart and put back together three times just because he could. Sophie got a rug with stars. Daniel got a key that felt like a promise.

One Saturday, Emily and Michael sat at a park bench that needed paint. Kids ran in clumps; a dog trotted like a mayor. Emily watched a boy of about eight in a coat too thin for the day, trailing behind his mother toward a corner store.

“I thought the world was only that corner,” Emily said. “Then it wasn’t.”

“Corners can be the beginning of streets,” Michael said. “If you turn.”

Emily turned the pencil in her hand. “Why did you help us?” she asked, not for the first time but with a different weight.

Michael took a breath. “When I was little, a neighbor named Mrs. Alvarez used to leave a bag of groceries outside our door every other Friday. She never said it was from her. But I knew. I promised myself that if I ever had more than I needed, I’d stand in doorways and not let kids go hungry on the other side.” His voice caught. He looked embarrassed at his own heart showing. “Also, you looked me in the eye that day. Most adults don’t. You did.”

Emily thought about the milk running into the gutter like a small river. She thought about how sometimes a thing spilling is the first proof it exists.

Spring wore on. Michael’s company signed a contract that meant more trucks, more routes, more everything. He hired Daniel part‑time in a maintenance bay that smelled like rubber and possibility. Daniel came home with black crescents under his nails and a loosening in his shoulders you couldn’t buy.

Not everyone loved the way the story had gone. There were people who said Michael had done it for publicity. People who said Daniel should have lost his kids. People who said Emily should be grateful in a way that looked like a bow. But the ones who mattered—the ones sitting at the table and the ones fixing the van and the ones reading the paragraph twice—knew different.

In June, the neighborhood association hosted a block party because this was still Chicago and people still knew how to pull a grill to a sidewalk and make a street feel like a living room. Emily helped Andrea run a table where people could sign up for a program Andrea had dreamed up and Michael had funded without asking for his name on it: Saturday Milk Club. Every Saturday morning, kids could come to the community center for breakfast and a grocery bag—no questions, no forms, no wristbands, just food and a hello by name.

Mr. Reynolds showed up with the store’s charity budget and a stack of coupons he had designed himself that said, in large type, EVERY KID DESERVES BREAKFAST. He stood at the edge of the crowd, unsure of his welcome, until Sophie marched up to him and declared that his store had the good cereal with the cartoon on it. Reynolds’s laugh startled him. He had not heard it in a while.

By July, Emily had a summer job shelving books at the library branch that never had enough money but had more kindness than any building in the zip code. She learned the sound books make when they’re ready to be read—spines creak like knees. Ms. Jennings stopped by one afternoon and slid a note across the desk. It was a scholarship application for a writing camp. “Just look,” she said. “Let the idea sit in your pocket for a while.”

Emily filled it out that night at the kitchen table while Daniel sanded a thrifted coffee table in the next room, turning rough into smooth with a patience that looked like prayer. Michael wrote a recommendation letter that said this girl notices things the rest of us hurry past.

She got in. On the first day, she wanted to bolt. The other kids looked like they already knew how to be the main character in a life. The instructor, a woman with silver hair and sneakers that had seen parks in other cities, asked them to write about a time they had been hungry. Emily wrote about milk and a sidewalk and a man who didn’t look away. It wasn’t pity they gave her when she read. It was attention, the respectful kind. She put the notebook in her pocket and felt it there like a warm stone.

On a rainy Wednesday in August, Daniel came home early with a sheen of panic on him. He had gotten a letter from a court about a child services review—one of those automatic check‑ins that feels like judgment even when you’ve done nothing wrong. He held the paper like it might cut him.

“We’ll go together,” Michael said. “We’ll bring Andrea and Lisa. We’ll tell the truth.”

The courtroom was smaller than television had suggested, and kinder. A judge named Caldwell looked at them over reading glasses and asked clear questions in a voice like a porch. Andrea described the home visits. Lisa explained the family fund. Daniel looked the judge in the eyes and said, “I messed up. I’m getting better. My kids are safe.” Emily spoke only when asked and said, “We have breakfast.”

Judge Caldwell made notes. “You have people,” she said at the end. “That matters more than most things.” She closed the file. “Keep going,” she added, which was the kind of sentence you can pin to a refrigerator.

September brought school and the clean notebooks that promise everything. Emily joined the newspaper club and wrote a piece about the Saturday Milk Club that made three kids who had been whispering at the back of the cafeteria show up with an embarrassed swagger and leave with powdered sugar on their lips. Liam joined a robotics club where he learned to build a small thing that did what it was told, which felt like victory. Sophie made a best friend with a laugh like a bicycle bell.

Michael worked and visited and tried not to make everything a plan. His mother had once said, “Love is not a spreadsheet,” and he wanted to remember that. He started seeing someone, a pediatric nurse named Rachel who understood why he kept a spare booster seat in the trunk and didn’t treat generosity like a magic trick.

On a cold Saturday in late October, a year to the week since the milk spilled, Emily walked down the block for eggs. The air smelled like last leaves and someone’s dryer sheet. In the store, she saw a boy around eight staring at a loaf of bread as if it might talk him into it. His fingers hovered. The clerk was busy yelling at someone on the phone about deliveries. The boy slid the loaf under his jacket and moved toward the door without moving his face.

Emily’s heart did the old thing. She stepped forward before he reached the threshold.

“Hey,” she said softly. He froze. “You don’t have to do that.” She set a carton of eggs on the counter and dug in her pocket for the emergency twenty Michael insisted she carry. “Let’s pay together.”

The boy looked at the floor. “It’s for my sister,” he mumbled. “She’s little.”

“I know,” Emily said. “I’m Emily.” She walked him back to the counter, put the bread on it like it was a decision they had made with pride, and stood there until the clerk looked up and rang it without sighs.

Outside, Emily handed the boy the bag. “You good to get home?”

He nodded. “Thanks,” he said, looking at her like she had invented a new rule of physics.

She watched him jog down the block and turn the corner. The wind made a little noise in the alley, a cat skittered, a bus sighed. Emily pulled her jacket tighter, not against the cold, but to hold something in—the fact that there are versions of you that will always exist, and that you can be kind to them even as you outgrow their shoes.

When she got home, she set the eggs on the counter and told her father the story. Daniel listened the way you listen when your kid teaches you how to be a person. He put an arm around her shoulder and squeezed once.

“You did right,” he said.

That night, Emily opened her notebook and wrote: I want to be the kind of person who says yes when the world says get out. She underlined yes three times. She drew a little box and wrote MILK inside it, then drew waves around it until it looked like an island and a sea at once.

Michael came by with Rachel and a tub of ice cream. They ate it out of bowls while the radiator apologized from the corner. Rachel read a picture book to Sophie using voices that made Liam pretend he didn’t care while he leaned in. Daniel told Michael about a promotion at the shop—nothing fancy, just more hours and a pay bump that meant he wouldn’t have to count quarters at the laundromat anymore.

On the balcony, after the kids were in bed, Michael looked out over the city, its lights making constellations of maybe. He thought about the corner of sidewalk where a small carton had exploded like a quiet comet, and about all the corners you can turn if someone turns with you. He thought about how his mother used to say, “Don’t get tired of doing good,” on nights when the goodness felt like a mop you had to wring out again and again.

Inside, Emily slept with a book under her pillow, because some habits feel like armor. In her dream, the store door chimed and nobody shouted. Someone asked if she needed help finding anything and meant it. She woke to a radiator clank and her father’s laugh from the kitchen. She slid her feet into slippers with worn heels and stood for a moment in the doorway, watching the morning start like a small engine catching. Love, she was learning, sounded like that—imperfect, determined, a little noisy, alive.

There are stories you tell because they happened and stories you tell because you want them to keep happening. Emily’s life, finally, was both. And when people asked her years later why she cared so much about tiny things—about milk and bus schedules and whether the library stayed open late on Wednesdays—she said, “Because tiny things are how you say to a kid: You matter.”

The city didn’t change because of one carton. It never does. It changed because one person stopped and then another and then a few more, until there was a path through the cold you could follow, even if you were small. And if you stood on that sidewalk a year later at the right time of day, you could still see the faint stain where milk had run and sunk in and fed the concrete some story it decided to keep. If you’re the kind of person who notices, you can see it. If you’re the kind of person who steps forward, you don’t need to.