My husband’s mistress became pregnant, and his family demanded that I divorce him to make room for her. I only smiled—and one sentence from me left all four of them pale with fear.

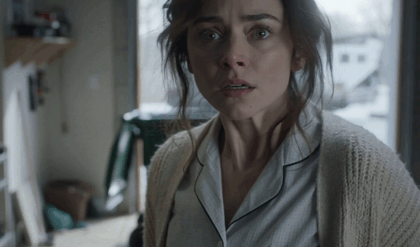

The clinking of cutlery against porcelain was the only sound in the Carter townhouse until Margaret raised her eyes from her plate. The silence wasn’t ordinary; it had the ceremonial hush of a verdict before it’s read, the way old churches fall quiet not from reverence but from dread. Across the long walnut table sat her husband, Daniel, his hands rigid at his sides as though there were handcuffs on the chair that only he could feel. To his right, his parents, Richard and Elaine Carter, wore the practiced calm of people used to writing checks to erase problems. Daniel’s sister, Caroline, perched at the far end with her chin tipped like a prosecutor about to make her closing.

“Margaret,” Elaine began, carefully folding her napkin as if the creases might keep the family together, “we need to discuss something… important.”

Margaret set down her fork and let her pulse regulate itself. She’d seen the late-night text bubbles that vanished when the bedroom door creaked; she’d caught the whiff of someone else’s perfume on Daniel’s cuffs; she’d heard the brittle laughter on a call he stepped outside to take in February wind. Knowing is different from hearing it spoken in a room you’ve paid to renovate. Still, she waited to be told.

“Daniel has made a mistake,” Elaine continued. “A woman—her name is Sophie Miller—is expecting his child.”

The words shattered the air like a dropped flute. Caroline leaned forward, her eyes glittering with the clean, efficient cruelty of the very clever. “You understand this complicates things. Sophie deserves her rightful place. She’s carrying the heir of our family. It is only proper that Daniel marries her.”

“You want me to step aside,” Margaret said softly.

Richard’s voice came like a gate slamming. “It’s for the best. Divorce quietly, make room for her. We’ll handle everything—financially, legally. It will be painless if you cooperate.”

Painless. The word almost made her laugh. Pain had lived in her ribs so long there were notches where it slept.

She lifted her gaze to each of them, the way an architect stands back from a blueprint and sees the steel for what it is. Daniel couldn’t meet her eyes. His family, however, looked at her like first-time buyers certain a seller would accept any offer.

Margaret took a breath and spoke, not loudly but with the clean line of a razor: “You’re asking me to walk away so Sophie can take my place? Fine. But you might want to rethink your timing. Because if I open my mouth—about what I know—none of you will survive the fallout.”

Richard’s fork clattered. Elaine’s practiced composure cracked like sugar glass. Caroline’s lips parted in a little O that wasn’t surprise so much as calculation interrupted. Daniel went white, as if she’d just dug up a secret he himself had buried and planted grass over.

Margaret leaned back and let the new silence settle. The power shift had begun.

The next morning, she stood barefoot in their stainless-steel kitchen, watching steam lift from her coffee like signal smoke. The winter light broke across the marble in long blue bands. She could still feel the tablewood under her fingertips; the weight of each pair of eyes on her as if they’d wanted to weigh her and find her light.

Daniel came in with his tie half-done, hair mussed into a boy he no longer was. He didn’t ask if she’d slept. He didn’t ask if she was okay. “What did you mean last night?” he said, voice low, brittle. “What exactly do you think you—”

“I meant what I said.” She didn’t raise her voice. “You think Sophie’s pregnancy is your family’s biggest problem? Try your father’s tax evasion. Try your sister’s little insider trading festival. Try the ‘donations’ your mother made to the hospital board to bury her malpractice case. Pick any thread, Daniel. When I pull, your last name unravels.”

He laughed—one hard bark that died before it finished. “You wouldn’t.”

“Oh, I would,” she said. “But I’m an architect. I prefer to build. So let’s talk structure. If I’m going to make room for Sophie, if that’s what your family demands, there’s going to be a framework, load-bearing, up to code. If they even breathe wrong about me, I will submit everything I have to the proper authorities and watch your father read my name in the business section he loves so much.”

His knuckles went white on the edge of the island. “What do you have?”

“Copies,” she said. “Emails. Ledger photos. Message threads. A schedule K-1 that doesn’t match the lifestyle. A ‘consulting’ invoice run through a donor-advised fund you called philanthropy. Caroline’s option plays the night before an FDA call. Elaine’s retainer check for a man who calls himself a lobbyist but files as a fixer. Would you like file names or will you take my word for it today?”

He stared at her for a long time, calculating the odds, and then left the kitchen without finishing his tie.

That afternoon, Elaine called. The older woman’s voice was varnished in control; underneath, it rattled. “Margaret, we may have been… too firm. There’s room to find a solution that works for everyone.”

“You mean a solution that keeps your family out of scandal,” Margaret said, and heard the pause that admitted the truth.

By evening, she had an appointment with an attorney—Paige Whitaker, her old roommate from Pratt who had traded studio critiques for courtrooms without losing her taste for clean lines and sharp corners. Paige read the situation the way she used to read Margaret’s models: carefully, a half-smile when she saw the hidden load paths.

“This is not extortion,” Paige said, flipping open a legal pad. “It’s leverage, yes, but legally framed. Any disclosures are to proper agencies and only if necessary to correct public misstatements or protect your interests. We’ll draft an agreement that’s airtight. House. Liquid assets. Existing art you purchased. Retirement rollover. And we build in a snapback clause: if they smear you, confidentiality lifts.”

“House first,” Margaret said. “I want the place in Brooklyn Heights. The townhouse with the south-facing terrace. And the deed in my name, free and clear.”

Paige nodded. “You always did draw the light just right.”

Brooklyn Heights had been a fantasy on walks when architecture school loans crowded out everything else. The Carters had bought the place as a “portfolio add”—investment disguised as leisure—and left it half-unlived, half-staged, as if a family could be installed like furniture. Margaret wanted a home that wouldn’t look at her and ask for pedigree. She wanted walls that would hold her without asking questions.

The next days unfolded like a gantt chart she hadn’t asked to manage. There was a lunch at the North River Club where Elaine arrived in winter white and the kind of diamonds that never learned their own weight. They sat by a window that made the Hudson look like an expensive material.

“You’re handling this poorly,” Elaine said after the second course, not bothering to pretend it was otherwise. “This is a sensitive situation. Gossip helps no one.”

“I haven’t said a word,” Margaret said. “But if I need to speak, I’ll do it where it counts. Do you know what a nurse keeps when she’s told to change a chart? A copy. Do you know where copies end up? In the hands of people who can read them.”

Elaine set down her fork with surgical precision. “You’re bluffing.”

“Elaine,” Margaret said gently, almost kindly, “you have excellent hands. What a pity about the night at St. Sebastian’s when you didn’t.”

For a second, the older woman’s eyes went glassy, then she blinked hard and brought the room back into focus. She asked for the check without finishing her entrée, and Margaret knew: the bribe had been small enough to be called a donation and large enough to step over a body.

Two days later, Caroline summoned Margaret to a café in NoHo with cement floors and baristas who spelled names like sentences. Caroline wore a blazer like a weapon and smiled without moving any muscles that might reveal effort.

“I admire the tactic,” Caroline said, stirring a coffee she would never drink. “But you don’t know what you’re in. You think you can threaten us and walk out whole? Do you think you’re the first woman who thought she could strong-arm a family like ours?”

“I think I’m the first woman to bring receipts,” Margaret said. “Would you like to see the photo of your burner phone on the nightstand reflected in your bathroom mirror? You tend to forget reflections when you’re texting before bed. Shall I forward the image of the brokerage confirmation from the night before the Redwood Biotech 510(k) announcement? Or would you prefer the chat log with Jason Kline at MidAtlantic Capital where he says—and forgive the spelling—‘we’re green tomorrow’? I’m fond of green. It’s the color of second chances and federal agencies.”

Caroline’s face didn’t change so much as it slid, the way glass looks unchanged until you realize it has shifted in the frame and nothing fits flush anymore. “What do you want, Margaret?”

“To be left alone,” she said. “And the Brooklyn Heights house.”

“Take the house,” Caroline said with sudden ferocity. “Take all the houses. You think you’re the only one he lied to?”

There it was—the crack Margaret hadn’t expected. Not sympathy, exactly. More like collateral damage acknowledging itself.

The Carters’ counsel reached out through the proper channels, and soon there was a date with a conference-room table at Whitaker & Lowe. The room had the sterile optimism of new buildings: frosted glass, potted plant, a view of midtown that flattened even power. On one side, Paige and Margaret sat with pens and the clean, cool stack of a proposed settlement. On the other, Jonathan Pike, the Carters’ attorney, flanked by a junior associate who typed with the panicked efficiency of a first-year who knows that typos are a kind of death.

“We are here to ensure discretion and a smooth transition,” Pike said, as if he were talking about moving a file, not a marriage. “Our clients are prepared to be generous provided Ms. Carter—”

“Mitchell,” Margaret said reflexively, giving him the maiden name she hadn’t said in years. It felt like unlocking a room where her favorite books had been stored.

“—provided Ms. Mitchell agrees to strict confidentiality and a mutual non-disparagement clause,” Pike continued. “We propose a lump sum, plus a reasonable allocation for property.”

Paige slid the stack across the lacquered table. “We propose the deed in fee simple to the Brooklyn Heights property, a lump-sum cash settlement payable within thirty days, the contents of the property aside from items specifically enumerated as family heirlooms to be removed within ten days by the Carters, and a rollover of Margaret’s retirement contributions from Carter & King Holdings with full vesting credited to the date of separation. Mutual non-disparagement. Mutual confidentiality. And a snapback clause: any public or private smear against my client voids confidentiality as to truthful statements necessary to correct the record. We will not be gagged and then slandered.”

Pike read. He did not react when he reached the snapback, but the associate’s hands paused at the keys. “The number,” Pike said, tapping a page.

“It’s not a number,” Paige said. “It’s a valuation of silence.”

“I refuse to pay a premium for—” he began.

Margaret leaned forward. “No one is paying a premium. You’re paying the market rate for keeping your name out of three different agencies’ in-boxes. I won’t need to lie. Truth is the sharpest thing I own.”

Pike glanced at the associate, then at the door where he was undoubtedly wishing a more senior partner would appear by magic. “We’ll revert,” he said finally.

They did. Within a week, there was a revised draft that conceded everything that mattered and haggled over things that didn’t. Margaret let them have the smaller paintings—Elaine’s taste skewed toward soporific landscapes that had never loved the walls they were hung on—and kept the sketches she’d bought from a RISD senior at an open studio because they made her think in angles again.

Outside the conference room, the city ran on like it hadn’t noticed a life cracking cleanly down the middle. Margaret took a car back to the townhouse she’d learned to walk through without brushing her hand against anything that didn’t belong to her and started packing the few items she’d bring to Brooklyn: books with her marginalia, the blender she’d bought with her first freelance check, the cobalt bowl that had held clementines all winter, her heavy sketchbooks, her laptops, the white shirt that fit her like an answer.

On a Tuesday in March, a smear piece materialized online in a gossip column that dressed itself in real news: A source close to the Carters says the marriage ended due to Margaret’s ‘instability’ and ‘fixation on work’… It went on to suggest infertility where there had been choice, and neglect where there had been accommodation. It was petty and broad; it clanged with the sound of someone throwing a metal bowl down a staircase and calling it a symphony.

Paige sent a one-paragraph letter to Pike that afternoon, citing paragraph 11(c), the snapback clause, and attached a draft declaration addressed to the SEC and the New York State Department of Health. Within three hours the column updated: An earlier version misstated private details of the parties’ marriage. We regret the error.

The first boxes arrived at the Brooklyn Heights house before the settlement check. Margaret unlocked the front door and stood for a long minute in the foyer, listening to air she could control. The place wasn’t grand so much as sane. The floors were old oak and the banister had a shallow worn groove where someone’s hand had practiced coming home. In the kitchen, south light spilled across butcher-block counters, and the back windows framed three honey locusts whose leaves would tremble like coins when spring finally happened.

She slept that first night on a mattress on the floor, boxes like soft walls around her, and woke to the sound of schoolchildren and a dog that sounded like a door knocker. She made coffee and opened a sketchbook. Lines arrived. Mass found itself. Between nine and noon, she drew the bones of a small community arts center the way you’d draw a place you needed as a child but didn’t have.

Within a month, she’d signed on as a project architect with Hale & Rusk, a mid-sized firm in Dumbo that liked the way she thought about daylight and egress and how people actually turned their shoulders to move through space. She worked late and went home earlier than she had in years. There were surfaces that accumulated her life the way countertops should: keys, mail, a grit of salt after a morning egg.

Sophie Miller existed at the edges like an echo. Margaret saw her once on a crisp April afternoon outside an OB clinic near Park Slope, Caroline hovering like a hawk who had agreed to midwifery in exchange for control of the nest. Sophie’s belly rounded under a slate sweater, her hair pulled into a practical ponytail that hadn’t learned how to exist under scrutiny yet. When their eyes met, Sophie’s expression was not triumph; it was the uneasy concentration of someone who had been told she’d won a prize only to realize the ribbon tied around it was braided from other people’s plans.

The second time, it was by accident at a café near Cadman Plaza. Margaret had a roll of trace and a cappuccino; Sophie had a cup of herbal tea and the posture of someone learning how to make room for another set of lungs.

“I didn’t know you came here,” Sophie said when the barista called her name and their gazes collided over the pastry case.

“It’s new to me,” Margaret said. She could have walked past. Instead, she gestured to the stool beside her. “Sit, if you’d like. I don’t bite.”

Sophie sat with the cautious relief of a person who has been told they are safe and still doesn’t quite believe it. “I didn’t set out to hurt you,” she said after a moment. “That doesn’t make it better. But I didn’t wake up and think, ‘I’ll take a husband away.’ It started like a lie you tell yourself about how grown-ups get to choose and ends like… this.”

“The Carters choose for you,” Margaret said, not unkindly. “Until you learn to speak a language they can hear.”

Sophie’s hand moved unconsciously to her belly. “I’m scared.”

“You should be,” Margaret said, and when Sophie’s eyes widened, she added, “which is not the same as being powerless. Keep records. Make copies. Don’t sign anything you haven’t had someone who loves only you read first. If they tell you something verbal ‘to keep it simple,’ ask them to write it down. If they tell you a number, add a zero and then ask for the paper trail.”

Sophie nodded like a student. “Why are you helping me?”

“Because they think they can write women out of minutes,” Margaret said. “You might be the mother of their heir, but you’re still a woman in a story they think they own. Also,” she added, surprising herself, “because none of this is the child’s fault.”

When Sophie left, Caroline was waiting on the sidewalk, her expression tight. She looked past Sophie at Margaret through the glass and didn’t bother pretending not to stare. Margaret lifted her cup in a small salute and went back to the section drawing she’d been working on. Stairs, properly drawn, are always hope: an invitation to go up.

The divorce announcement arrived in May, written in the kind of joint language that pretends life is a mutual untying. Amicable, it said. Respect, it said. It left Sophie out entirely, which meant the Carters had decided the public would accept a story about two adults who simply grew apart. Margaret allowed the fiction. Silences have to be curated, too.

Daniel texted twice the week after the statement. Can we talk? I’m sorry. Margaret typed a reply that said, I hope you become the man you thought you were, and deleted it without sending. The third message came at 2:11 a.m.—I don’t know how to fix anything—and she did not answer that either. He would learn. Or he wouldn’t. Either way, her life couldn’t hinge on a man learning.

Hale & Rusk won the bid for a small waterfront library in Red Hook that summer, and Margaret found herself at community board meetings where teenagers talked about somewhere to sit after school and a retired longshoreman named Frank told her he used to read in the cab of his truck between shifts. She drew a reading room with high windows you could look out of and not feel watched. She fought for quiet HVAC because books should not have to compete with machinery to be heard. She requested brick that would age into the neighborhood instead of sitting on it like a new tooth cap.

In August, a private investigator tried to enter the Brooklyn Heights house by the garden door at three in the morning. The motion-sensor light tripped. The camera caught a pale oval of a face, a license plate, and a distinct pattern of streetlight shadows on the back of a gray SUV. Margaret sent a still to Paige without commentary. An hour later, a brief note went to Pike: Please advise your clients that any further attempts at unauthorized access will be met with immediate police involvement and a protective order. See attached. There were no more attempts.

Sophie gave birth in September to a little boy the gossip pages named before the parents did. Margaret did not read the article; a photo found her anyway—Sophie in a hospital bed, damp hair stuck to her temples, eyes raw with love and terror. The baby’s head was the size of one of Margaret’s hands. She closed the tab and sent a soft cotton blanket from a small shop in Maine with no note, no return address. One less thing for Caroline to weaponize.

After the leaves turned, an invitation arrived at the Brooklyn Heights house to a Carter Foundation gala at the American Folk Art Museum. Margaret held the heavy paper and pictured the way donors tilt their heads when they hear something they already believe said in a new accent. She RSVP’d no with a line that could not be interpreted as anything but a line.

On a Thursday in November, a man from a magazine you only see in airport lounges called to ask if she’d like to be profiled as “a woman of reinvention.” “No,” she said, and hung up. The next morning, a photographer from a design blog asked if she’d pose in her home office. “Also no,” she said, and went back to her section cut of the children’s nook for Red Hook.

Daniel appeared once, in person, on a street in Dumbo where the view under the bridge makes everyone feel like they’re in a movie and behaving accordingly. He looked older in a way that was not about time so much as soot. “I keep wanting to say there’s another version of this where we’re okay,” he said, hands in pockets like the cold had asked him to surrender. “But I think I was only ever okay because you were holding everything up.”

“That sounds heavy,” Margaret said. “You should set it down.” She didn’t smile. He didn’t ask for forgiveness because he finally understood it wasn’t a currency she traded in.

A week later, news broke—in a column that actually did fact-checks—that the SEC was investigating unusual trading activity around Redwood Biotech. Caroline’s name did not appear. Jason Kline’s did, once, near the bottom, a footnote to a footnote, but it was enough for a sophisticated reader to follow the line with a finger and wonder where it went. Margaret did not celebrate. She did not tip. She made soup and worked on the library’s stair detail and texted Paige a single period. Paige sent back a single period. They were building a language that did not require adjectives.

The Red Hook library broke ground in March under a pale sky that promised rain it did not deliver. The teenagers came with their parents. Frank wore a cap that said Retired but Reading. Margaret put a shovel in dirt like a citizen instead of a wife. When the news photographer asked for a quote, she said, “Public space is a love letter to people you don’t know yet.” He looked confused. She didn’t explain it.

On the first hot day of June, Margaret came home to find an unmarked envelope wedged into the doorframe. Inside was a single photograph: Sophie holding the baby on a blanket in a park, eyes closed like she was saying a prayer to something that did not require worship. On the back, in neat handwriting, it said, Thank you for the blanket. It’s his favorite. I am trying to be brave. No name. No return address. Margaret slid the photo into a drawer with warranty manuals and the kind of paper you only open when something has broken. She didn’t tell anyone she kept it.

By autumn, leaves blew like confetti down Hicks Street, and Margaret stood on her terrace watching the light even out. She had a tan line where her watch had been and a groove on her middle finger from the pencil she used to prefer over pens for sketching. Inside, the living room held a couch she’d chosen herself and a small stack of library books that would be late by two days because she’d rather pay the fee than force an ending before she was ready.

She thought sometimes about the first time she met Daniel—at a gallery opening in the East Village where the art felt like a dare and the wine tasted like it had been poured through bouncers. He’d told a story about a broken water main outside his office and made it sound like he’d wrestled the city to a standstill and won on points. She had laughed. She had been twenty-five and full of opinions that had not yet calcified. He’d liked that she was good at lines. She had liked that he was good at telling them.

There were days when she forgave him in theory. There were days when she forgave herself in practice. There were days when she remembered that the body keeps score and the mind revises it.

On a Tuesday in late October, Margaret walked to the edge of the terrace and watched the windows come on across the street like a chorus admitting it was time to sing. The city hummed the way it does when it’s not performing for anyone. Her phone buzzed on the table behind her and she didn’t turn to look. She breathed in, lungs wide as the room she’d made for them. The air tasted like cold and the possibility of soup.

Somewhere across the river, Richard Carter was likely reading three different newspapers and finding none of the words he feared most. Elaine was probably at a board meeting, speaking about patient outcomes in a voice that had already forgotten the donation that ensured one of them would never be counted. Caroline would be sitting in a chair you can only buy if you think about chairs more than you think about what it means to sit. Daniel would be holding a child and learning to be still.

Margaret rested her palms on the warm brick and let the skyline be what it was: a habit of steel and light and people who believed in the audacity of staying. Her lips curved into the same small, private smile she had worn the night she watched four faces blanch at one sentence. It was not triumph exactly. It was something quieter and more permanent. It was the structural integrity that comes after you’ve ripped out a load-bearing wall and discovered you could replace it with something beautiful that holds.

She turned and went inside to her draft table. The Red Hook library had a detail that still wasn’t right; the stair at the back wanted to be a little wider so a parent and a child could walk side by side and still breathe. Margaret picked up her pencil and drew the width they would need. Then she drew the landing, and the next rise, and the next, until there was a way up that felt like a promise she could keep.