The first strike didn’t hurt Lena’s body—it shattered her heart. It was the sound, a wooden crack that didn’t belong in a home with lavender curtains and a pot of rosemary chicken soup simmering on the stove. The cane had belonged to her father, a gentle man who used it to steady himself on their front porch in Fort Collins and to tap out rhythms when he told stories. In Lena’s mind, it had always been a metronome for patience. In Ryan’s hand, it became punctuation for contempt.

The late Denver sun fell in slanted gold through the kitchen blinds, dust motes freckling the air. Lena’s belly, seven months along, pressed warm and heavy against her apron. She’d spent the day padding a nest out of ordinary things—fresh sheets, folded onesies on the dryer, soup that smelled like Sunday. She wanted quiet, and the kind of dinner where a married pair returns to eye contact rather than the habit of passing each other like strangers in a hallway.

The door opened. She heard Ryan’s shoes first, that clipped sound like he didn’t want to be heard at all. Then the second set, the delicate click of heels. When Lena turned, a young woman followed him into the living room. She was beautiful in a way that begged to be looked at—smoky eyes, sleek blowout, a scarf knotted the way you learn from magazines. She looked around as if it were a rental she was considering.

“Ryan?” Lena’s voice snagged. “Who is she?”

The woman smiled without warmth. “I’m Melissa,” she said. “And I’m the woman he actually loves.”

Lena set down the spoon. The soup burped a little, a domestic sound that made the room feel grotesque. “You’re joking,” she tried, because jokes are the last flares we send up before a ship disappears.

Ryan’s mouth flattened. The man who once spilled pancake batter on Sunday mornings and kissed the stain on her shoulder had been eroding for months, coming home late, showering immediately, letting his phone vibrate face-down on the coffee table. Stress, she told herself. Everyone struggled at work sometimes. Everyone drifted and returned.

“You should leave, Lena,” he said, as if asking her to pass a salt shaker. “I’m done pretending.”

“Now?” Her palm went to her stomach, instinct before thought. “When I’m carrying your child?”

“You trapped me with that baby.” His voice thickened. “You always wanted to tie me down.”

“I wanted a family with my husband.” Lena reached for something steady in the room—the counter edge, the rhythm of breath—then saw the cane in the umbrella stand by the door, her father’s old ash wood, and felt her world tilt. Ryan had never liked that cane. He said it was rustic in a city home.

He moved fast. The cane’s wooden tip clipped her forearm before she could raise her hand to protect herself. Not a hard blow, not the worst blow she could imagine, but it wasn’t pain that mattered. It was the audacity of it. The certainty that he was allowed. Lena stumbled, knees cracking the tile, and in the shock of falling she thought of baby names and crib slats and the way the nursery window caught morning light.

“Give me the keys,” Ryan barked. “You don’t belong here anymore.”

Melissa crossed her arms, nails shining like tiny knives. “You heard him,” she said. “Leave before you embarrass yourself further.”

The front door burst like a dam. Three men filled the threshold and made the room feel small in a new way—height and control and anger leashed like a storm-dog barely kept at heel. They took in the tableau without speaking: Lena on the floor, one hand on her belly; Ryan with the cane; Melissa with the smirk she’d learned for less dangerous rooms.

Ethan Bennett spoke first. The eldest brother had a banker’s posture and a scar on his chin from falling off a bike when he was seven and still insisting it didn’t hurt. He ran Bennett Capital, the kind of firm that made headlines when markets trembled.

“Put it down, Ryan.”

Ryan swallowed. He had never liked how the Bennetts occupied space. He’d told Lena that men like that were always performing. “It’s not what it looks like,” he started.

Lucas Bennett stepped around the couch, palms open at his sides like a negotiator and eyes like a programmer turning over a problem. He’d built Silverline Systems from a dorm room in Boulder into a cybersecurity fortress with a skyline office smelling faintly of espresso and ambition. “She’s pregnant and you hit her,” Lucas said, every syllable clean. “There’s nothing else to see here.”

Melissa opened her mouth, but Noah Bennett’s stare found her. He had the quiet of a logistics king—Horizon Freight’s networks of trucks and ships, friendships with dock bosses and union reps, a map of America in his head. “One more word,” he told her, voice not raised, “and you’re going to wish this city had never learned your name.”

The cane hit the rug like a small surrender. Somewhere in the house a faucet dripped. Lena’s breath rode in shallow waves. Ryan said something, a messy tangle of grievance and fear, but the brothers had already shifted from fury to procedure. That was the way they moved through crisis—they built scaffolds where other people shouted.

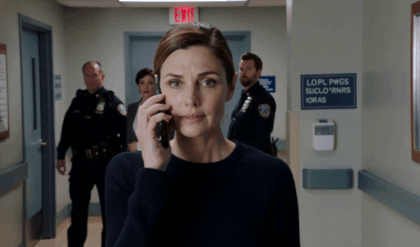

Ethan’s phone was at his ear, voice steady. “We need an ambulance and a patrol car at 514 Maple Ridge,” he said, giving the cross street. “Pregnant woman assaulted.” He listened, gave a yes, gave another yes, then crouched beside his sister and touched her shoulder like touching glass. “You’re okay,” he murmured. “We’re here.”

Lucas slid the stove knob off and moved the pot to a cool burner before the soup turned or the house burned down. He grabbed a clean towel, wrapped it around Lena’s arm where the skin purpling at the edge already looked like a bruise shrugging up from underneath.

Noah took two steps forward and positioned his broad frame neatly between Ryan and Lena as if measuring something with his body. “Keys,” he said to Ryan. “Lease, mortgage, any document you think gives you leverage—get your hands off all of it.” He didn’t shout because men like him never needed to. “Security’s on the way,” he added. “Until then, you don’t touch my sister. You don’t breathe on her.”

Melissa laughed, high and thin, a sound that belongs in salons and not in living rooms where nurses will soon kneel with blood pressure cuffs. “You can’t just—”

Noah looked at her again, and she swallowed the rest.

The sirens came quick and merciful. On the porch, neighbors watched with their hands in the pockets of the same hoodies they wore to Broncos games. Denver knows how to stare without being seen. The EMTs carried a cool competence that soothed Lena more than any words could. She let them strap the cuff around her arm, let them press two fingers under her jaw, let them angle the monitor to show a steady heart. She felt the baby flutter and then, as if he too had needed the reassurance of a pulse line, settle.

The officer who took the report had young eyes and old posture. He listened. He asked once, “Did he strike you?” and nodded when Lena answered. He cataloged the cane into an evidence bag, a humble weapon turned artifact. He did not look at Ryan when he explained the terms of a temporary restraining order, and that insult—that a man in uniform would decide the story—made Ryan flush the color of shame or rage; Lena couldn’t tell.

Ethan rode with Lena in the ambulance, knuckles white on the side rail when the driver cut a tight corner. Lucas followed in the SUV; Noah stayed to escort the officers through the rest of the house, pointing out the nursery, the photographs, the simple proof of a life built and meant to be safe. Melissa hovered on the lawn until she realized there were no applause lines left for her. “Call me,” she hissed to Ryan, and he didn’t.

At Presbyterian St. Luke’s, the hallway smelled like lemon cleaner and hope. A nurse with a badge that read TORI smiled with her whole face and said, “I know this is terrible, but I promise you we do terrible really well. We do it every day.” She rolled the fetal monitor into place, found the heartbeat—galloping, defiant. Lena closed her eyes at the sound. The world narrowed to that little percussion. Ethan pressed his forehead to her temple, something he hadn’t done since childhood when thunderstorms made them all small and holy.

Lucas returned with a coffee nobody would drink. Noah brought a sweater from Lena’s closet and a picture of their parents from the living room shelf; he set it on the tray table like a talisman. Their father’s cane in a bag, their father in a frame. How the past resurfaces when the present tries to drown you.

“What if… what if the baby—” Lena began, fear a living thing clawing at her ribs.

“He’s okay,” Tori said, and nobody in the room corrected the pronoun. “He’s strong.” The nurse squeezed Lena’s hand. “So are you.”

By midnight, the paperwork had the rectangular finality of a stamp. Temporary restraining order. A report with boxes checked. “Follow-up,” scribbled in black ink. A domestic violence advocate named Mariah with a calm voice and a business card that had been slipped into a thousand trembling hands. The three brothers read every line, not as CEOs but as brothers; then as CEOs again, because power does not turn off when you go home for the night.

In the morning, the living room looked cleaner than the night deserved. Sunshine always lies a little. But the Bennetts arranged the chairs as if rearranging them could sculpt a new life. They waited for their family attorney, a gray-haired woman named Ruth Lin who had once cornered Ethan at a charity gala to correct him on a comma and had represented them ever since.

Ruth wore sensible shoes and carried a leather portfolio that had seen courtroom floors in three states. She shook Lena’s hand first. “I’m sorry for what happened,” she said plainly. “You’re safe now, and we’ll keep you that way.”

The plan rolled out like blueprints. Divorce papers drafted by noon. Emergency motion for exclusive occupancy of the marital home—that would be easy with the restraining order. A petition for temporary support; details of the joint accounts Lena didn’t even remember signing because Ryan had always done the paperwork. Ruth looked at Ethan. She knew who he was on magazine covers; she also knew he was a brother and that this mattered more.

“I can freeze the joint accounts,” Ethan said, and Ruth raised an eyebrow. “Through the banks where we,” he corrected—“where I have relationships. Enough to keep the funds from being bled dry before the court can see them.”

“Do it if you can do it legally,” Ruth said. “Let the judge bless it in a day or two. We’ll file an affidavit. We want this clean.”

“We’ll keep it clean,” Lucas said. His laptop hummed at the edge of the coffee table, a silver slice of strategy. “I can pull down the cloud backups. His messages to Melissa. Hotel confirmations. Delivery receipts. He’s sloppy.”

“He always was,” Noah put in, the way people who move freight know about the fragility of boxes and men. “And I’ll make calls. People hire because they know you and because they know me. They’ll know what he did, and they’ll know we don’t work with men who do this.”

“No blacklists,” Ruth said, because someone had to be the conscience when rage wanted to be the whole room. “But you can tell the truth. You can tell your truth to people who ask.”

“We’re not violent men,” Ethan said, and he looked at the cane in its plastic bag as if apologizing to its memory. “We are men of consequence. Let’s proceed accordingly.”

By Thursday, Ryan learned what consequence felt like when it is lawful and relentless. HR called him into a glass-walled conference room and explained that the firm could not be associated with a domestic violence arrest, that client retention required decisions he might find unfair. He tried to tell them it was complicated. They nodded with faces trained to hold empathy and PR in a single expression. He turned in his key card and felt the limpness of the lanyard in his palm as a private insult.

On Friday, Melissa stopped answering. She was supposed to meet him at a coffee shop with pendant lights and succulents, but she texted a single line: I can’t do this. He read it five times, looking for a code in the white space. On Saturday his credit card declined at a gas station off I-25 with a wind-whipped flag in the distance and a teenager at the register who looked like every age Ryan had never stopped to be. On Sunday, when church bells did their work and the Broncos fans wore their optimism like armor, Ryan called his mother and lied about why he couldn’t come over.

Lena did not watch any of that. She took her vitamins with the carefulness of a ritual and went to a doctor who measured her blood pressure and said the words “within range” like blessings. She let Mariah, the advocate, come over on Tuesday with pamphlets and statistics and a laugh that made you feel like you had already survived. She propped her feet on the ottoman Ethan had bought her and finished the baby blanket she’d been crocheting in a tricolor stripe—navy, cream, sky.

At night, when the house thinned to creaks and the baby’s kicks were the only punctuation, she would occasionally allow memory to return. Ryan on a beach in California on their honeymoon, trousers rolled, his shy toe against cold water. Ryan singing off-key at a Christmas party, arm around her shoulders, confetti in his hair. Ryan as a boy in a story his mother told—sensitive, inhaling hurt like oxygen, spending his life exhaling it into other people.

Ethan started arriving at the house before dawn the way bankers do when markets open in other time zones. He sat with a legal pad and wrote lists that looked like prayer and looked like logistics and looked like love. Lucas came by at lunch to install a new security system with cameras that were so discreet they felt like secrets kept rather than secrets spied. Noah organized a rotation of people who would always be present—cousins, old family friends, a neighbor with a dog who needed a lot of walking, everyone with a casserole and a favor to ask and a reason to knock.

The divorce process, when it began, was both simple and full of paper. Ryan retained an attorney with a too-shiny watch who used phrases like “exaggerated allegations” and “marital discord” and who listened when Ryan insisted that the baby had been a trap. Ruth listened too and then slid across the table a stack of photographs, hospital records, printouts of texts in which Ryan promised Melissa Parisian weekends in hotel rooms in downtown Denver. After the third exhibit, the shiny watch stopped reflecting so much light.

“When you stand in front of the judge,” Ruth told Lena in a prep session that felt like rehearsal for a role no one wanted, “you tell the truth. You don’t need to be dramatic. Your life already is.”

The hearing was set in a courtroom with a ceiling so high it made everyone smaller in the right way. Lena wore a navy dress because navy looks like dignity and because Lucas had said it made her eyes do a thing he couldn’t name. Ethan sat directly behind her, his hand on the back of her chair. Lucas took notes even when nothing was being said. Noah stared straight ahead and didn’t blink for long stretches of time the way he did when watching weather move across a map.

Ryan, across the aisle, looked tired in a way that money can’t fix. He glanced at Lena once, then away, then back, like you look at a place you used to live and are not sure what you’re allowed to feel. When the judge asked Lena to describe what happened, her voice shook at the start and steadied as truth built its own scaffolding. “He struck me with my father’s cane,” she said. “I was holding my belly. I asked him to stop. He didn’t.”

Ruth asked for photographs to be admitted, and they were. She asked for hospital records to be admitted, and they were. She asked for the text messages to be admitted, and they were. Ryan’s attorney objected to something and was overruled. It all felt like architecture—the way facts assemble into rooms where everyone can see each other.

When the judge ruled, the words fell into the air with the weight of law. “Full physical and legal custody to Mrs. Carter,” she said. “Exclusive possession of the marital home to Mrs. Carter. Spousal support in an amount to be determined at the next hearing. A restraining order, no contact, not within three hundred yards.” The gavel came down like punctuation that did not invite argument.

Outside the courthouse, a reporter tried to angle for a quote, and the Bennetts closed ranks around Lena without touching her, the human version of a privacy screen. Someone took a photograph anyway, and it ran on the lifestyle page next to a piece about a new brunch spot in LoDo. The headline read not about wealth or scandal but about a woman who had done an ordinary, extraordinary thing: left.

“Is it over?” Lena asked in the car, watching the city move past, mailmen, a woman with a stroller, a runner with neon shoes.

“It’s over,” Ethan said, because she needed someone to say a finite word even though life rarely gives those. “What comes next is living.”

What came next surprised Denver more than it did the people who had always understood the Bennetts. Two weeks after the hearing, the three brothers hosted a gala at the Hyatt that people would have called obscene if they didn’t know what money can do when it gets tired of buying boats. The invitation said only: A Pledge, A Fund, A Next Step.

Under crystal chandeliers that had seen too much of the superficial and were hungry for substance, Lucas took the stage and didn’t talk about product or profits. “We’re here because a house that smelled like soup and sunlight became a place where a woman was told she didn’t belong,” he began, and the room—filled with executives, artists, teachers, a chef who wore her whites like armor—fell silent. “We’re here to say that our companies will not fund abuse. Not with our contracts, not with our silence, not with the cynicism that tells us these stories are private.”

They unveiled the Bennett Pledge, a simple document that said any company wanting to do business with Bennett Capital, Silverline Systems, or Horizon Freight would need to maintain a zero-tolerance policy for domestic violence convictions among executives, provide paid leave and resources for survivors on staff, and agree that if an employee was credibly accused and the company protected him because he was a rainmaker, those contracts would end. It was not blacklisting; it was refusal to align. Lawyers had combed it, ethics professors had weighed in, HR experts had added clauses to make it workable rather than punitive.

Ethan announced the Bennett Fund for Safe Futures, a $25 million endowment to shelters across Colorado and to legal aid organizations like the one Ruth sometimes volunteered with on Saturdays. Noah, last to speak, told a story about loading a shipment of children’s beds one winter to a shelter in Pueblo and how the driver had called in crying because he’d seen a woman touch a new pillow like it was gold. “We move things for a living,” he said. “Tonight we move lines. We move lines in a way that is hard to move back.”

The room stood. Not in the way rooms stand for applause when they’re supposed to. In a way that said something had shifted. Not everyone signed the pledge that night. Some took it back to boards and HR and fear. Some signed in a line that snaked past the dessert table. The Denver Post used the word “unprecedented,” not something they got to use much in a city that prided itself on common sense.

Ryan watched this on his phone in an apartment he rented by the month in a building with thin walls where he could hear the neighbor’s blender in the morning. He didn’t understand how three men could bend a city without raising their voices. He sent a late-night email to a former colleague asking for a referral and got a note back that said, Sorry, man, messy situation. He tried to be angry and ended up being tired.

Lena did not attend the gala. She was home with a book she didn’t read, her hand collared over the bump where her son had begun to practice scrums. She read the article the next morning while eating toast and cried for reasons she couldn’t rank. Relief and grief and gratitude and something like awe at the way her brothers had turned their fear into architecture the rest of the city could enter.

“Good men should be boring,” Mariah had told her once. “Mostly boring. Do the dishes. Keep their hands open.” Lena thought of that as she loaded the dishwasher and laughed a little at the sound of plates finding each other in their slots.

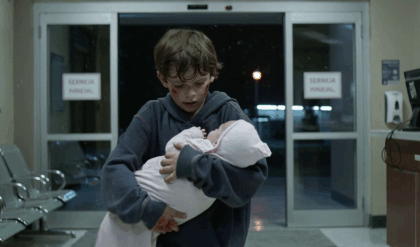

The baby arrived in late March when the air tasted like snow and asphalt. Labor started at 3:14 a.m., the time everything hard seems to decide to begin. Ethan drove like a man balancing caution with the knowledge that you can turn a red light green with money only in cartoons. In the delivery room, Lucas kept count on contractions under his breath as if coaching a server deployment. Noah stood guard by the door in the way of men who feel most useful when the perimeter is known.

Lena named her son August James Bennett Carter, because August sounded like a month and a virtue—dignity, gravity—and James had been their father’s middle name. When the nurse laid August on her chest, he blinked without drama at the world he had entered. He had Lucas’s mouth, Ethan’s brow, Noah’s quiet. Probably she was projecting. Maybe all babies look like the men who love them.

The first weeks were a tangle of gummy smiles and laundry. Sleep became a lottery. Lena learned the topography of her house at night so as not to kick the ottoman. On Tuesdays, the Bennetts came over to take turns walking a circuit from nursery to living room to kitchen and back while narrating in deep voices the thrilling tale of a stuffed giraffe with a loose ear. On Fridays, Mariah stopped by with stories from the shelter—good stories, the kind you tell to feed hope. “A woman got the job,” she’d say. “Another got the apartment with the good light.” Lena fed the fund with small checks and big prayers.

Ryan texted once, a week after August was born: Is he okay? Lena didn’t respond. Not because she wanted to punish, but because she wanted to live. The restraining order made it simple, the emotional math made it cleaner. In the quiet after feeding at 2:37 a.m., she wrote a letter she didn’t send. She told the truth to a person who wouldn’t read it. It felt like a ritual the universe had invented for her. She folded the paper and put it in the box with the baby’s hospital bracelet and the hat with the pom-pom.

Spring threw green at the city with a kid’s messy joy. At a park in Wash Park, Lena pushed August in a gently swaying motion that mothers do across continents and centuries. A woman on the bench next to her pointed to the fund’s logo on a flyer tacked to the community board. “Those Bennett brothers,” the woman said, half skeptical, half impressed. “Who knew?”

“I did,” Lena said, then immediately wondered if that sounded boastful. She turned to the woman, a stranger she would not meet again. “It’s not revenge,” she added. “It’s just building a world where people are a little safer.”

“Close enough to the same thing,” the woman said, not unkindly, and took a long drink of her iced coffee.

Ryan moved to an apartment further out near the refineries where the sky looks metallic at dawn. He took a job that didn’t require college or conversation. He lifted boxes and counted pallets and thought a lot about gravity. Sometimes, when silence got heavy, he drove by the old neighborhood and watched from half a block away as Noah stood on Lena’s porch holding August like a football against his chest, the gentleness of that incongruity making Ryan’s throat ache. He thought about walking up. He thought about the cane. He drove away.

The court dates became less dramatic and more administrative. Papers filed, signatures inked, a judge who had six other cases before lunch. The divorce decree arrived folded into a thin envelope that did not understand its own weight. Lena opened it at the kitchen counter and touched the raised seal like it was Braille and would tell her a story other than the one she already knew: over.

She took down the cane from the hall closet where it had lived since the police returned it, evidence chain broken, chain of memory intact. She carried it to the backyard and buried it under the lilac bush that struggled every year and still found a way to bloom. “I can’t have you on a wall,” she told the air. “But I can make you food for something that smells like spring.” It felt right; it felt wrong. That’s how healing usually feels, she learned. You make peace with imperfect rituals.

In June, when Denver air turns thin and afternoons threaten thunder, the Bennetts hosted a barbecue that in any other family would have been loud and in theirs was somehow both calm and immense. August was passed like contraband between aunts and cousins. Ethan stood at the grill wearing an apron that said KISS THE COOK in a font entirely too cheerful for his boardroom face. Lucas organized a cornhole bracket like a TED Talk. Noah sat on the steps and taught a five-year-old how to tie a shoe.

Ruth came by, demurring when Lena tried to hand her a plate piled too high. She ended up staying until dark, the kind of dark that in cities is never total. As she left, she hugged Lena in that careful way lawyers learn to hug clients, then did it again without any of that training. “You did something people write op-eds about,” Ruth said softly. “You left. You told the truth. You made it easier for the next woman to say the words.”

“I had three brothers and a city,” Lena said. “That’s not fair to people who don’t.”

“No,” Ruth agreed. “And until it is, we build scaffolds. We put more hands under the weight.”

The Bennett Pledge traveled. A tech firm in Seattle called to ask for language. A freight company in Memphis borrowed the clauses and added their own. A boutique fund in Boston sent a note that said, We’ve signed. The fund that had begun as money became beds and bus passes and hours of legal counsel and statehouse testimony and a discount at a locksmith who had ten survivor stories and no business model for them. It was not enough. It was not nothing.

One afternoon in August—August in August, the symmetry of it making everyone laugh—Lena drove with her son to the foothills. She parked where the view scraped sky and held him on her hip, pointing. “That’s the city,” she said. “That’s the place where you were born. That’s where your uncles turned a promise into a building you can’t see because it’s laws and ideas. That’s the lilac bush where a story is buried. That’s your home.”

August gurgled, unimpressed with metaphor. He tugged at her hair and found a fistful of it and let go when she said “gentle” in the tone mothers use when they are teaching and begging at the same time. A hawk circled overhead. Somewhere below, a truck on the highway sounded its horn like punctuation.

Back in the car, her phone buzzed with a text from Ethan: Board vote unanimous. Expansion to Pueblo. From Lucas: Wait till you see the dashboard on the shelter logistics—game-changer. From Noah: Rangers game tonight. You’re coming. No excuses.

She smiled because she had learned how again. She drove home with the windows down and the radio on and did not check the rearview mirror more than once. She pulled into the driveway that was hers and carried her son up the front steps that were hers and unlocked a door that was hers and set him down on a rug where he would one day throw a tantrum because the world had taught him he was allowed to feel big and safe at the same time.

“Welcome home,” she told him and maybe herself.

On nights when sleep was a straight line rather than a scribble, Lena sometimes stood in the doorway of the nursery and watched the rise and fall of August’s chest. She thought of all the rooms where women did this, all the quiet vespers whispered over cribs and bassinets and rented mattresses, all the promises made in the dark. She thought of how fragile and fierce a vow can be. She remembered the crack of wood and the crack of a gavel and the crack of dawn on the day her son came into the world. She stood there longer than she meant to stand and then went to bed.

In the years that followed, Denver would tell the story in the way cities do—condensed, with a headline. They would forget the smell of rosemary soup and the exact shade of the towel Lucas wrapped around his sister’s arm and the particular patient kindness of a nurse named Tori. They would keep the simple skeleton: A man hit a woman. Three brothers did not hit back. They built instead. The city followed.

When August was six, he asked about the cane because children have a way of finding the buried things just by existing. “It was your Grandpa James’s,” Lena told him. “It helped him walk when his legs were tired. Then it became something else for a minute in this house, and we decided it should become part of a lilac bush instead.”

“Can I see it?” he asked.

“You can see the bush,” she said, and they went out and he looked at the spray of purple like a boy encountering an ordinary miracle. “It smells like a good day,” he declared. She agreed.

Sometimes, rarely, Lena would see Ryan in the produce section or at a stoplight. He would raise a hand halfway and then let it fall. She would nod without smiling because forgiveness did not require theater. He looked older. She felt older in the way survivors feel older and also, somehow, more new. She wondered if he had learned to inhale something other than hurt. It wasn’t her story to finish.

On the anniversary of the night the door had opened and closed and opened again, the Bennetts gathered with pizza and a sheet cake too large for five people. They sang, badly and on purpose. Ethan toasted with club soda. “To the quiet,” he said. “To the scaffolds. To the lilac.”

“To the nurses,” Lucas added.

“To the drivers,” Noah said. “To every person who picks up a box and moves it and makes something easier.”

“To August,” Lena finished, holding her son’s sticky hand. “Who will grow up knowing that love is softness with a spine.”

They ate cake on paper plates that bent a little under the weight, and nobody minded because some structures are meant to flex and not break. Someone told a story about their father that made them all laugh too loud. Someone washed dishes. Someone took out the trash and then stood for an extra minute under the porch light, listening to the city beyond the yard hum like a giant refrigerator. The lilac bush held the evening breeze the way good memories do—gently, with the suggestion that if you stood very still, you could hear the root system talking to anything that needed to feel held.

Lena lay in bed later and thought of vows again. The ones we make at altars and in courtrooms and under our breath in the car at red lights. The ones we make over kitchen sinks and hospital sinks and bathroom sinks where we splash water on our faces and tell ourselves it will be okay. The ones we keep because people are watching and the ones we keep because nobody is. She closed her eyes and believed them.

Far away, in a building with flaring lights and fork lifts, Ryan finished a shift, sat on the tailgate of a truck, and stared at the place where the sky goes soft at its edges. He did not think of revenge. He did not think of pledges. He did not think much at all. He breathed in. He breathed out. It was something like a beginning. Or maybe just the middle of a life where the best thing he could do for the story was to stop writing himself into other people’s pages.

In a city that has learned to move mountains with ordinances and kindness, in a house that smells faintly like lilac and laundry, a woman slept and dreamed a dream without fear in it. A baby snored, small, and then turned his face toward the window where the morning would begin. A cane turned into flowers under the soil. A pledge turned into payroll lines that meant safety. A headline turned into a thousand tiny, boring good decisions that kept pain from spreading.

And that, more than any gala or gavel, was the shock that lasted: not that three CEOs could bend a room, but that they chose to bend themselves toward gentleness and law, and that a city, startled to find itself better than it had imagined, decided to keep going.