I opened the door at a little past six with sleep still sanded in my eyes and my flannel shirt not quite buttoned right, expecting nothing more dramatic than the thin breath of Adirondack morning and a cup of coffee strong enough to stand a spoon. I stepped onto the porch, yawned, and looked up into the kind of sky that looks newly washed. Then I froze. Standing three paces away, halfway in shadow, was a black bear the size of a small truck.

She didn’t move. I didn’t move. The trees did all the moving for us, shivering in the light breeze that smelled like cold pine and river stone. She wasn’t huffing, popping her jaws, or swaying in that warning way you read about in pamphlets; she just stood there like a statue with breath, her sides trembling, her fur wet in patches as if she had walked through rain no one else felt. I would have bolted for the old shotgun hanging above my kitchen door if not for the thing she held soft in her mouth.

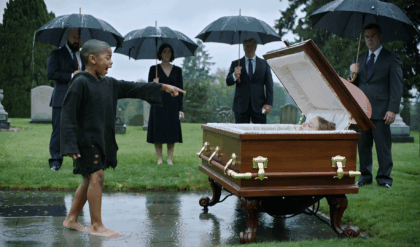

It was the limp, sodden body of a cub.

The cub’s legs dangled the way a child drops a rag doll when sleep wins. Blood had dried around one ear into a dull rust halo. I didn’t think animals could look like they were crying, but the mother’s eyes were wet and open and so unwaveringly focused on me that the porch, the rails, and the world beyond them seemed to dissolve until there was nothing but her and the life she had carried to my doorstep.

“Okay,” I heard myself say, the way you hear yourself in phone messages, detached and a little stupid. “Okay.”

I, Aiden Brody, claimant to the empty titles of ex-journalist and almost-novelist, a man famous to exactly one gas station cashier for buying two different brands of coffee out of indecision, did the kind of thing people in my old newsroom would have written off as metaphor or madness. I backed up slowly, kept my palms open, and motioned toward the boards at my feet. The mother took two careful steps onto my porch. She laid the cub down on the wood as gently as I’ve ever seen anything set on anything, then sat back on her haunches and kept her eyes on mine as if she were waiting for the rest of my sentence.

“I’ll try,” I whispered. My heart was a fist on a snare drum. “I’ll try to help him.”

When I crouched, every headline I’d ever edited about wildlife gone wrong clanged through my skull. But the bear didn’t lunge or warn. I slid my flannel off my shoulders and wrapped the cub as if the shirt had been invented for this purpose. The body was cold, not the clean cold of lake water but the deep cold that tries to move in forever. When I lifted him, something fluttered against my fingers—either a breath or my own pulse. I backed toward the door and stepped inside my cabin. The mother didn’t follow. She lowered her head, inhaled like she was memorizing the air, and settled where she could see me through the doorway.

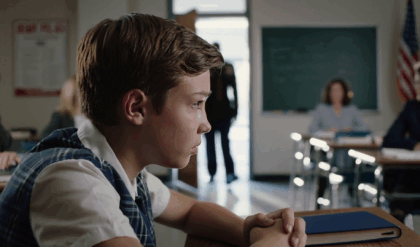

My cabin was a single wide-open room carved from salvaged beams and stubbornness, situated on a ridge above a sliver of the Ausable. The Adirondacks were supposed to fix me—less siren, more wind, fewer deadlines, more trees—after years of writing about disasters that stayed curled behind my ribs even when I closed the laptop. I had fled Manhattan on an off-season Tuesday with two suitcases, a dented truck, and a phrase my editor muttered as a joke: go write something that doesn’t look at you in the dark. I had no plan beyond coffee, woodstove, and sentences.

Now a bear was looking through my door. And her child breathed thinly in my hands.

On autopilot, I set the cub on my sagging sofa and fussed with towels, the space heater, whatever blankets I could find that smelled more like laundry than man. I rummaged through drawers for a digital thermometer that hadn’t worked since a flu season before vaccines. The cub’s fur was wet with a metallic smell my brain filed under emergencies. One hind leg didn’t lie right. A swollen ear had clotted ugly. I pressed two fingers to his ribs and waited, counting, bargaining. There—a tremor under bone. Not much, but not nothing.

“Hang in, little man,” I said. “Breathe on my watch.”

Outside, the mother shifted. The porch board creaked under her weight and the hairs on my neck rose with it. I needed help, and not the philosophical kind. I grabbed my phone and scrolled to the only vet I knew well enough to call before sunrise.

“Rachel Kowalski,” came the answer on the second ring, voice thick with sleep and unamused by surprises. Rachel ran a country practice out of a converted dairy barn just north of Keene and had saved more farm dogs than most angels.

“Rachel, it’s Aiden,” I said. “I have a bear cub.”

“Excuse me?”

“A bear cub. On my sofa. His mother brought him. He’s in bad shape.”

Silence stretched far enough for me to see my own absurdity. “Aiden,” she said finally, “how much of last night’s bourbon is still in your bloodstream?”

“I swear,” I said, too loud. The mother lifted her head at the threshold. “I swear to you I am sober and facing an impossible situation. What do I do?”

Rachel exhaled a long, one-cuss-word sigh. “Okay. Warmth first. No solid food. If you have honey, mix a teaspoon in warm water and give drops with anything like a syringe. Don’t get bit. Do not, absolutely do not, open your door wider than a crack. I’m calling Ginny Stiles—she used to work the North Country wildlife rehab. We’ll be there as fast as the roads allow.”

The call ended. I found honey in a cupboard behind a lonely can of beans and an ambitious bag of quinoa. I warmed water, swirled in amber, and filled a turkey baster while telling myself it was a syringe’s country cousin. I dripped sweetness onto the cub’s tongue. Nothing happened. I tried again, then again. On the third try his tongue made a small, skeptical motion and a feeling like a flare went off in my chest.

“Good,” I murmured. “Prove me foolish for doubting you.”

Minutes expanded into a wide field of waiting. I talked to him because quiet felt like surrender. I told him about the wind ferrying the scent of balsam, about the old logging road that ribboned behind my cabin, about the coffee I still hadn’t made and the editor I didn’t miss. At some point his paws twitched as if asleep in a memory of running. I cleaned the blood around his ear with hydrogen peroxide I would have hesitated to use on myself, and he flinched so hard I nearly cried with gratitude for the pain.

The mother outside made a sound like the last hinge squeak on an old gate. I opened the door no wider than my hand and met her eyes. “He’s still with us,” I said. She breathed in and out, slow, as if those breaths were the most disciplined acts in the world.

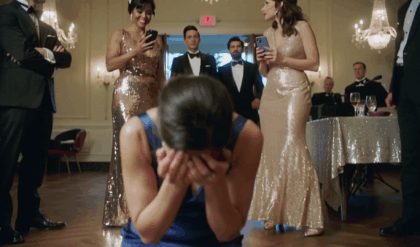

By the time Rachel’s Subaru pulled up with a shiver of gravel and a cloud of road dust, the cub had taken a dozen more swallows, and his chest rose a little deeper. A second car stopped short behind her, and a woman in a field vest stepped out with a bag big enough to camp in. Ginny had hair in a practical braid and a face free of the kind of expressions that spook animals.

“Holy hell,” Rachel said when she saw my living room triage. “You actually weren’t joking.”

Ginny didn’t waste any words on amazement. She kneeled beside the sofa and set to work—cleaning, assessing, injecting, binding—with a quiet efficiency that felt like permission to breathe. “Adult male bite,” she said after inspecting the hind leg and ear. “Big one. Sometimes boars kill cubs to bring the sow back to estrus. This little guy is lucky his mother is stubborn and that you were home.” She looked up at me as if weighing more than facts. “Names make it harder,” she added, like a doctor telling a parent not to googlediagnose.

“I haven’t named him,” I lied, though a syllable had been forming uninvited in my head since I wrapped him in my flannel. Baxter. I had no idea why.

They stayed for hours. The mother melted into the treeline, not gone so much as reposed at a distance where her presence turned into a feeling. Rachel and Ginny left me with antibiotics, a dosing schedule, and the one instruction I didn’t want: this is temporary.

“You’ll call me if he crashes,” Rachel said, one foot already in her car.

“You’ll call me before he imprints,” Ginny added. “Or before the state hears from a neighbor.”

I didn’t ask what happens when the state hears from a neighbor, because I already knew.

We made it through the day measured in drops and breaths. Near dusk, a thing like a miracle performed itself in slow motion. The cub opened one eye. It was the color of dark tea and it found me, not past me or through me but me, in a way that made my lungs forget their job. The look wasn’t gratitude or need. It was the recognition you feel when another living thing maps you onto its world as a fact instead of a rumor.

“You’re not alone,” I said, and meant both of us.

In the days that followed, our cabin truce hardened into a routine that would have made for a poor pitch to my New York editor and the perfect plot for my neighbors’ gossip. I warmed fluids, crushed antibiotics into honey, replaced bandages that he tried to worry off with his teeth. He slept the heavy, re-making sleep of the truly exhausted. He woke and wobbled to a bowl of water as if it had appeared by magic. He tucked his face into the tangle of blankets and made a noise like a broken accordion someone loved anyway. The swelling in his ear receded; the punctures on his leg closed; the weird hitch in his gait became less weird.

The mother came most mornings and some evenings, a presence at the edge of the clearing, the shape you notice only because the forest has a rule about where shadows usually are and she broke it. I placed berries and a scoop of birdseed well away from my porch like a man passing notes to someone he wasn’t supposed to know. Sometimes it disappeared. Sometimes not. She never tested my door. She never rolled the grill. She never did anything a pamphlet would blame her for. She waited.

It was on the eighth morning—funny what you count when you’re living between systems—that Deputy Louise Gentry drove up with her county-issue Tahoe, its front seat littered with coffee cups like a constellation. I’d met Louise in the checkout line at Stewart’s when we both reached for the last blueberry muffin. She’d let me have it and given me a card that said call if you ever hear gunshots and don’t know why.

“Word is you’ve got yourself a houseguest,” she said, thumb hooking her vest in what I had come to recognize as her prelude to bad news.

“Word moves fast for a place with slow roads,” I said.

“I can slow the word down,” she said, “but not stop it. DEC’s already got wind. They’ll send an ECO out in a day or three. If they see a cub under human care, they’ll look for a crate. If they can dart the mother, they might move her. If they can’t, they might do something else. Depends on the officer, the history, and who’s on the phone at Albany.” She studied me. “I’m not a villain here, Aiden. I like bears where bears belong. I also like people unbitten.”

“Understood,” I said, though what I understood was that some clocks don’t tick, they hum.

After she left, the cabin felt smaller. The cub—Baxter, don’t say it—tumbled in a circle with a found tennis ball as if joy had been switched on. He crawled onto my lap, heavy with health and the kind of trust that doubles as a warning label. I pictured a clipboard in an ECO’s hands and a signature line under the word euthanize that would stay blank but not unimaginable.

I drove into town to the Blue Heron Diner where the coffee is strong, the pie is aggressive, and the bulletin board still features lost cats from the nineties. Cal Whitaker, a DEC officer whose uniform always looks freshly ironed even when he’s wrestled a drunk out of a canoe, was cutting his pancakes into precise squares.

“Hypothetically,” I said, after the small talk that counts as taxes in small places, “if someone were to encounter a cub in distress in the orbit of a mother, and that someone provided temporary care to keep the cub alive—hypothetically, mind you—what would the state prefer happen next?”

Cal chewed slowly, stared at me, then at the window, then back. “Hypothetically, the state prefers bears that don’t know what kitchen smells like,” he said. “Also hypothetically, the state hates responding to calls where a sow loses her mind because a well-meaning human created a bad pattern. Hypothetically, the best exit is to reunite them in the same drainage and let the forest handle the paperwork.”

Hypothetically, indeed.

That night I wrote a plan on the back of an old grocery list. Load the cub into a big plastic tote layered with the blankets that carried my cabin’s trace scents. Drive slowly toward the drainage where I’d seen the mother vanish on those first days. Leave the tote open. Back away. Watch for as long as my heart could stand it. Then let go.

But plans drawn on grocery lists belong to something better suited to plans than life. When the morning came, the sky threatened rain and my own courage felt like a bad battery. Baxter nuzzled my elbow while I wiped down the kitchen counter, because he’d learned that nuzzling my elbow produced attention. The mother lingered in the firs as if she’d been told to wait and was following orders. I filled the tote. I lifted Baxter. He made a surprised snuff that sounded like what an apology might be to a bear.

Driving the logging road felt like steering down my own throat. Every root looked like a decision I couldn’t take back. I parked at a clearing where the ground held prints large and small like a family album. I set the tote down and opened the lid. Baxter blinked against a column of light. He stood, a little cocky on legs that had come back to him, then sat again and turned to look at me as if I’d moved the furniture without asking.

From the far edge of the clearing came a sound so soft I didn’t hear it as much as feel a hand press into the air: the mother, calling in a frequency that registered in the muscle before the ear. Baxter’s head swiveled like a compass needle deciding on north. He stepped out of the tote, put one paw on the pine duff, then another. He took three unsure steps in the direction of the sound. He stopped and looked at me again.

“Go,” I said, and I don’t know whether I was telling him or myself. “Go be what you are.”

He went. Not bravely, not dramatically, not in a sprint—he went like a creature who has discovered that the world is not a hallway but a room with more than one door. He walked until fur met fur and the clearing acquired a shape that made sense. The mother lowered her head, tested him with her nose, breathed his neck like reading a book in a language only she remembered. Then she lifted her gaze to me. We stared again across the space where porch boards had not been invented, and something that wasn’t a bow passed between us—more like a small admission that none of us were alone in the business of deciding.

They moved into the trees, one large shadow and one small. Before the smaller became indistinguishable from the larger, he jolted back toward me in a little, foolish dash and pressed his face against my jeans. I put a hand—ridiculous, warm, human—on his head. “Goodbye,” I said, and the word cracked like old paint. I nudged him toward the darkness that was not absence but habitat. He went. The mother waited for him to catch up, then they were gone, and the clearing was just a clearing again.

It took a long time to carry the empty tote back to the truck. It took longer to put away the blankets because folded fabric is not grief but it can stand in for it. I boxed the toys I’d sworn not to give him and climbed the pull-down stairs to my attic where I keep the ghosts I choose. I told myself a story about a man and a bear in which the man does the right thing and the bear does the bear thing. I told it until it began to sound true.

Weeks passed. The woods remembered how to be only woods. I walked the trail behind my cabin and looked for sign the way a former reporter checks five sources for a rumor nobody cares about. Sometimes I found scat full of berries and thought it meant them. Sometimes I found tracks and told myself they were old when they were not. I returned to words that did not look at me in the dark and to coffee that did. My phone stopped buzzing with warnings from Louise and questions from Rachel. The world steadied.

On a morning in October when the first cold snapped the leaves into their better colors, I opened my door to a neat pile of late raspberries arranged on the top step like a child’s offering. There were no human footprints. There was only a smudge where something heavy had leaned in close enough to be careful. I laughed in a way that felt like a confession and carried the berries to the edge of the clearing, setting them down in a little echo of the gift.

After that, the offerings came once every autumn week or two. A mound of beech nuts. A half-dozen blackberries, too symmetrical to be accident. Once, a smooth oval stone the size of a heart, streaked with a quartz lightning bolt, which is the kind of thing I would have called corny in my city life and now placed on the mantel with stupid reverence. I did not tell anyone about the gifts. I did not want the story to become an argument.

When winter shut the last doors and the trails hardened under a crust that cracked loud under boots, Louise parked at the bottom of my drive and tromped up with a paper bag of bakery sugar cookies that made sense only because that was what we had. We drank coffee at my table while the steam fogged the cold corners of the glass.

“You did right,” she said, uninvited to my private courtroom but delivering a verdict anyway. “DEC closed the file they never opened.”

“Does DEC open files on things that didn’t happen?” I asked.

“Every day,” she said. “You spared us all paperwork and a bad headline.”

Rachel stopped by in March with worming paste for a farm dog and a carton of eggs from a patient who paid in eggs. She reached up and touched the quartz streak in the mantel stone. “New?” she asked, eyes sliding to mine with practiced veterinary innocence. I shrugged so hard I almost dislocated a shoulder. She let me have my secret.

The book I’d been trying to write for two years changed under my hands. The voice softened in places and sharpened in others. The sentences moved like animals instead of trains. I wrote about the ridge above the river, about mornings when the fog stayed low like it had lost its map, about the difference between being alone and being singular. I did not write about bears. You don’t use a breath you might need later.

In late May, when the ferns were uncurling and the mosquitoes had remembered their jobs with terrifying efficiency, I hiked the long loop past the old fire road. Near a muddy stretch where deer often printed their resumes in cloven script, I found tracks—two sizes, one big, one smaller, the smaller almost the size of my palm. They were fresh enough to capture the slosh of water returning to itself. I crouched and set my hand beside them. My hand looked ornamental by comparison.

I did something ridiculous. I spoke to footprints. “Thank you for the berries,” I said, because gratitude made more sense than silence even there, especially there.

That summer, a group of downstate hikers asked at the general store if anyone knew the guy with the carved bear statue on his shelf. “Just a souvenir,” I told them when they stopped me in the parking lot to confirm my identity, because the truth matters and also because the truth fractures if you expose it too often to weather.

“From where?” one of them asked, delightfully earnest.

“From here,” I said, and it was the only honest answer.

On a hot September evening when the katydids produced enough noise to knock thought loose, my editor—yes, I still had one in the digital, often absent way editors exist now—called to say the new pages felt like they were written by someone who had remembered how to risk something. “You went to the mountains to get quieter,” she said. “And you did, but not in the way I expected. Keep going.”

I did. The book found its shape. It wasn’t about wildlife or miracles or men changing into saints. It was about a person learning the difference between tending and keeping, between guarding and holding on. I finished the manuscript on a morning when fog had left perfect beads on the porch railing like a rosary I didn’t know how to use.

On the day I printed the last page, I drove to the Blue Heron and ordered a slice of every pie they had because there are events that require more than one flavor. Cal happened to be there again, slicing his pancakes into his fussy squares.

“You look like a man who just did something hard,” he said.

“I did something long,” I said. “Sometimes they’re the same.”

He lifted his coffee. “To long things, then.”

The first real snow came early that year, a clean slate nobody asked for. The tracks I found in the yard were mostly rabbit, some fox, one coyote that had passed through like a rumor. I did not expect to see bear sign because sensible bears were denning by now and sensible men were stacking their firewood inside reach. But on an evening when the moon scraped silver on the ridge and the temperature cinched tight enough to squeak, I heard a sound outside—a soft weight against wood, a pause, a soft weight again. I opened the door to the cold. On the top step, someone had arranged spruce tips in a neat fan. It wasn’t food. It was prettier than that.

I stood there shivering in shirtsleeves like an idiot, then did the thing we keep visiting this world to do. I set a small gift of my own on the step: a handful of dried cranberries, a glug of honey hardened onto a flat rock. I closed the door and leaned my forehead against it, the wood cold as a lake in April. Somewhere in the trees a log cracked under the weight of snow, making that deep gunshot sound the first winter always does. Somewhere else, closer, a branch whispered back into equilibrium.

In the morning the rock was licked clean.

Years will go by. I’ll forget how long the hospital smell lived in my flannel. I’ll forget which towel I cut into strips and which I promised my mother I’d wash carefully because eucalyptus fabric softener offends the natural order. I won’t forget the way the mother bear looked at me on a porch built for coffee and ended up hosting a bargain. I won’t forget the weight of a tiny head pressed lightly against my leg by a creature who would never understand property lines and would never need to.

Sometimes a couple from Boston or Syracuse or Sweden will rent the cabin next ridge over and stop by in mismatched boots, asking what a person is supposed to do up here besides look and breathe. I tell them to look more and breathe better. If their eyes ask for more I tell them about the old fire tower on Saint Regis or the way the light falls at five at Chapel Pond or the diner pie cut so thick it could be used as insulation. If they touch the quartz-striped stone on my mantel I tell them it’s just a rock with an interesting vein because it is and because it isn’t and because both can be true in the same world without either breaking the other.

And once in a while, on the kind of dusk that makes you believe in almosts, I’ll see a dark shape move where the clearing smudges into forest. I’ll hold still, which is a kind of prayer they don’t teach you as a kid. The shape will become a bear and the bear will become two bears and the smaller will be not so small anymore. They’ll slide past the edge of my property like rumors, like blessings, like a story that knows you even when you’d rather it didn’t.

If anyone asks me what changed me, I could say the move or the silence or the work. The truth lives somewhere else and walks on four legs. It showed up at my door one morning in a body carried carefully by another body, and it asked me a question without a word: can you be trusted with what is not yours to keep? I said yes, though my voice shook. I had thought saying yes would mean holding on. It meant letting go in the right direction.

On the shelf above my desk sits a wooden carving I bought from a roadside stand on Route 73 the week I turned in my manuscript. It is not sophisticated art. The bear’s back is wrong and the snout is too blocky and the eyes are those generic black glass beads they sell by the pound. I love it in a way that embarrasses me. Visitors ask where I got it and I tell them the truth: from a man with a chainsaw and a thermos who carves bears in a gravel lot in Keene. What I don’t tell them is what it carves out of me every time I look at it. I set my coffee under it in the morning the way other people light candles. It is an object that points at a story that points at a life that points at a forest that points at something I don’t have a word for and never will.

If you require proof, I can offer only raspberries on a step, a honey-slicked rock, and the silence between two creatures who looked at each other across a porch and decided to risk the middle ground. It is not the kind of evidence that wins arguments. It is the kind that builds a home inside your ribcage and hangs its coat on a nail you didn’t know was there. It is enough.

On certain mornings I still open the door half asleep and step out expecting nothing more than air with a little pine in it. On those mornings I find only what I asked for and that is plenty. But every so often the woods hold their breath in a way I recognize and the hair along my forearms lifts, and then from just beyond the old split-rail fence comes the single clean crack of a stick, and the world, which has never once been tame, feels generous again.