Columbus, Ohio, had a particular way of holding its breath at midmorning, just after the school buses left the quiet streets and the leaf blowers started up. The campus bells from Ohio State floated across the river like coins tossed in a fountain. A bus stop announced itself with the compressed sigh of brakes and the squeak of doors. Coffee shops smelled of caramelized sugar and wet wool in winter, of cold brew and sunblock in July. The shelter on Kenny Road sounded like metal bowls and mops and the rhythm of animals remembering how to hope.

That morning, the air tasted like disinfectant and biscuits. Emma trailed her graphite cane in an arc, listening to its tip dribble and click along tile grout. Her mother, Dana, walked a step behind, the whisper of her scrubs a familiar sound she’d learned to love: nurse shoes, microfiber jacket, the world’s most reliable metronome.

“Left,” Dana said gently.

“Got it.”

The Franklin County K‑9 Transitional Center had a lobby that blew hot air along Emma’s cheeks, then cooled to the stillness of a hallway. She smelled rubber gloves. She smelled wet fur and detergent and the faint metallic note she had learned to associate with nerves—the tang of adrenaline left behind by fear.

“Ms. Callahan?” someone said. The voice had the calm weight of authority and the frayed softness of twelve-hour days. “Dr. Kincaid. We spoke on the phone.”

“Hi,” Emma said, turning toward the sound. She smiled into the space just to the right of it—she’d found that most people felt seen that way. “Thanks for letting us come.”

“We’re glad you’re here,” said Dr. Marilyn Kincaid, and her hand was warm when it shook Emma’s across the counter. “We usually start visitors in the therapy wing. Lower energy dogs, lots of praise, lots of treats.”

Emma nodded, cane sweeping, mapping. The acoustics shifted—the scuff of shoes to her right, the hollow echo that meant open doorways, the occasional high, bright bark. Somewhere down the hall a deep sound rumbled, too steady to be a growl and too contained to be free. It sounded like a storm rehearsing under a closed sky.

They’d come because Emma had promised herself she would stop being afraid of her future. She was sixteen. People could call that young; to Emma, it was an age that required new verbs. She had lost her vision at nine, the aftermath of an infection that left her with static and fog and then nothing—just the strange echo of light the way we remember music after it ends. Since then, she had learned the rules of rooms and the grammar of steps. She’d learned Braille and the lift of heads when the cane tapped open a space. But she had not yet learned the animal language she’d always wondered about—the conversation between a person who can’t see and a partner who decides to be her eyes.

Guide dogs had been whispered into her life for years by teachers and counselors and well-meaning strangers. “When you’re ready,” they’d said. “When you’re older.” After a winter of icy sidewalks and one close call when a silent electric car made a left turn that the cane could not argue with, she asked her mom if they could at least go meet some dogs. At worst, she’d get licked by something with a happy tail. At best, she’d meet a voice.

They started with a golden retriever named Sunny, whose breath smelled like apples and whose head found Emma’s lap as if it belonged there. Sunny’s handler spoke in a soothing stream Emma couldn’t follow because she was too busy petting velvet ears and listening to the dog’s contented huffs. Another dog, Clover, leaned against her shin with a weight that could anchor ships. Emma laughed. Each dog was a warm punctuation mark in a sentence she hadn’t known how to finish. She could have stayed all day.

But the rumble at the end of the hall kept re-appearing between her laughs like thunder behind the glass of a museum display. She tilted her head toward it without meaning to. On her tongue: the iron taste again. On the back of her neck: a prickle that was neither fear nor curiosity but some braid of the two.

“What about him?” she asked softly.

“Who?” said her mother.

“The one that sounds like a truck idling.”

Dr. Kincaid hesitated. Silence changed shape—a sudden careful stillness people make when they’re measuring how to tell you no. “Duke,” she said at last. “Former K‑9. He’s… in rehab.”

“Rehab,” Dana repeated. The word carried two histories in it: the drug counseling she did in the ER, and the physical therapy she guided after surgeries. To Emma, it was the word they used when people needed a patient miracle.

“Do you work with him?” Emma asked.

“We try,” Dr. Kincaid said. “He came to us after a line-of-duty incident. His handler was injured on a raid. Duke shut down. He redirected on the next two handlers we tried to pair him with.” She exhaled, a brief gust. “On paper he’s ‘unfit for service.’ Off paper he’s a maze we haven’t found the map for.”

“Is he dangerous?” Dana asked, and Emma felt her mother’s hand brush her shoulder in that half-second touch that meant I am nearby for whatever comes next.

“He can be,” Dr. Kincaid said. “But so can a storm. It depends what land it crosses.”

Emma said, “I want to talk to him.”

“Sweetheart,” Dana began, and Emma heard the way her mother tucked fear into endearment.

“I just want to talk,” Emma said. She stood, aligning cane, spine straight the way her occupational therapist had taught her. “I think he’s tired of commands.”

They moved down the hall, slow and careful. Emma could feel the temperature change—colder near the end, dry air fanned by a vent. The smell shifted too, less detergent, more dog. The rumble cut in and out like a low engine. Footsteps slowed behind her. She pictured a hand hovering over a keypad, a body between her and a gate. She pictured a thousand kinds of concern wrapped in the shape of professionals who had seen bad things happen.

“Stop here,” Dr. Kincaid said softly.

Emma stopped. Metal sang in front of her: kennel bars, the faint ring of it when a tail hit. A soft scratch tapped the floor. The rumble dipped. She felt, on her skin, a stare like weather.

She breathed out.

“Hello, Duke,” she said. “I’m Emma.”

The rumble flattened into silence.

“You sound angry,” Emma said, “but I think you’re scared.”

No one had trained her to say those words. They had trained her to lift the cane just so, to count steps and feel for braille labels on changing room doors, to use apps that spoke street names. They hadn’t taught her how to talk to an animal that had given up, but Emma had spent enough nights learning to coax her own heart out from under a bed of fear. She knew how to meet a panic attack like a person: with names, with patience, with what if we stayed instead of ran?

Behind the bars, something big shifted. The clack of nails stepped closer. Emma lifted her hand, palm open, not close enough to touch the metal. She kept her wrist turned, fingers loose, so if he lunged she could drop back without clanging, without disrespecting the space.

“You don’t know this,” she murmured, “but I can’t see you.” She smiled toward the sound of his breath. “Everybody says you look mean. I don’t believe that yet. I haven’t met you.”

The silence turned into breath. Slow. Fast. Slow again. The smell of dog came clearer, a warm animal smell like laundry just after the dryer, like old leather. Emma’s hand trembled. She kept it there anyway.

“Emma,” her mother whispered. “Maybe that’s enough.”

“It’s okay,” Emma said. “You don’t have to be afraid, Duke.”

The rumble dropped into a small sound that broke her heart—the creak of a whine the dog tried to hide. Then a single warm exhale puffed across her fingertips. She didn’t move. He decided. His nose touched the meat of her palm and froze there, a weightless weight. Emma swallowed the sob that rose like a fast balloon. Slowly, she turned her palm just enough for his bones to find a home at the base of her fingers. He leaned. The bars separated them and didn’t. All the air in the hallway held still to listen.

“See?” she whispered. “You’re safe.”

The sound that followed started with fur on metal and ended with a body settling onto concrete. Heads turned. Gloves squeaked. Somewhere a clipboard creaked. Emma felt the tears slide cool down her face and didn’t bother to wipe them. She lifted her other hand and rested it on the steel. Duke pressed his skull against the bars, the way someone who has been given bad news will press their head into their folded arms. His whole body trembled. The tremble moved into her bones as if fear could be conducted and turned to warmth by touch.

“You miss your partner,” she said, understanding with her skin what her eyes might have missed. “I’m sorry.”

He whined, a note so thin it barely existed, a filament of sound that anyway held the weight of grief.

From that day, Emma came back every morning.

It wasn’t a plan at first. It was a sentence she couldn’t stop writing once she began. School made room—she adjusted two classes to later periods and promised to keep her grades above the line. Dana argued and then did what good mothers in messy lives do: she learned how to help it happen safely. She got refresher training on bite protocols. She bought a pair of Kevlar‑lined gloves and kept them in the glove compartment. She told Dr. Kincaid, “I trust you,” in a voice that meant I am trusting you with my child and with the part of my child that says she is old enough to choose this.

They started with reading. Emma brought paperbacks from the dollar bin and traced the wrinkled pages with her fingers like prayer rugs. She read aloud slowly—the cadence she used when she read to herself in Braille sometimes carries over to speaking—and Duke breathed. He didn’t approach the door at first. He didn’t even lift his head most mornings. But he didn’t growl either, and sometimes Emma heard his breath sync to her voice. She read him mysteries and memoirs and the kinds of books that pretend to be about dogs but are really about people.

Some days she didn’t read at all. She sat there and hummed songs she knew by heart. She didn’t have a perfect pitch that made people lean in, but she had a clean note that landed where she put it. She sang “Let It Be” two dozen times over three weeks without apology because the lyric put tenderness in her mouth like honey.

They added quiet into the routine the way you add a rest into music. Fifteen minutes of nothing. No words. No humming. Just two creatures sharing air separated by steel. On the fourth day of that silence, Duke rose and pressed his shoulder against the gate like he’d remembered why bodies were made.

On the twelfth day, they opened the kennel door.

“On your terms,” Dr. Kincaid told Duke. “We’ll give you space. You give us a moment of trust.”

Emma sat on the floor two yards away, cross-legged, cane laid across her lap like an instrument at rest. She had put on the Kevlar gloves but hoped she wouldn’t need them. “Hi,” she said into the room, not louder than any hello might be, careful not to add an edge. “I’m here.”

He stepped out. She heard the pads hit tile, the skitter of nails corrected into control. She felt him choose his speed the way she could feel a car ease up to a stop sign. He went past her first, a circle around the room, collecting the information of smell: the lemon cleaner, the ghost of other dogs, stale coffee, her shampoo. He stopped in front of her shins and breathed, the warm dog smell a free blanket.

“Okay,” she said.

He lay down. The sound was both nothing and everything: a scuff, a thump, the exhale of something that hadn’t exhaled properly in months.

“Can I?” she asked.

He didn’t answer, because dogs don’t, and also because he did. She reached forward, slow, stopping just before contact. He made that low, barely audible whine again and nudged her knuckles. Then she touched him.

His fur was shorter than she expected, dense like a new toothbrush, with a slickness on the top of his neck where the harness used to sit. Scars raised along his left shoulder like punctuation she had no alphabet for. Under her fingers, muscle hummed like quiet power, like a car idling with the parking brake on. She wanted to cry for him, for the man he’d lost, for the kid she still was who wanted to be braver than fear. Instead she breathed and counted each inhale to ten. His breathing found a place to match it.

“Good,” Dr. Kincaid whispered from the doorway, the relief so covered in professionalism it sounded like expertise.

Emma didn’t ask for Duke. Not that day. Not the next. She didn’t turn the way a teenager might when they want something and begin to collect reasons and pitch them like folded paper across a dinner table. She waited to see if what she felt in that room could grow into something with a leash.

The center had rules she learned with the diligence of someone who knew how rules keep you living. No unsupervised contact. No fast movements. Emergency stop word: “Blue.” No scented lotions on her hands. No treating him like a stuffed animal when he was a war veteran in a different kind of war.

On day twenty-one, a man walked into the room and the air changed.

Emma didn’t need her cane to tell her there was a uniform involved. Uniforms carried their own weather. They made a crisp noise when arms moved, a whisper of nylon and Velcro and a weight that sounded like radios. She smelled gun oil and aftershave that was clean and old-fashioned. Duke stood in a single sound. He didn’t rumble. He didn’t whine. He made the kind of silence that has shape.

“Officer Delgado,” Dr. Kincaid said softly. “Thanks for coming.”

Emma pushed her palm flat against the floor for balance and stood. “I’m Emma,” she said.

“Ma’am,” he answered, and if the word made her smile it wasn’t because she wanted respect, it was because the word itself was so careful, like a man stepping through a ruined house.

He took two slow steps into the room and stopped. “Hey, partner,” he said.

Emma felt the word pass through Duke like a tremor. She didn’t reach for him. She kept her hands loose at her sides and her weight balanced. Duke didn’t move. His tail didn’t tag the floor. He just stood there, breathing like someone deciding whether to run or to collapse.

“I’m sorry,” Officer Nate Delgado said, and his voice did a thing grown men’s voices rarely do in mixed company—it broke. “I’m sorry I wasn’t there when you needed me to be.”

The story came later, the way stories do once the hugeness of the moment is done with you. A warehouse on the west side. An informant who was right until he wasn’t. A flashbang that ricocheted. Screams. The sound of men’s feet trying to be quiet in chaos. Duke had found the stairwell first and cleared the landing like he’d been taught, body ahead of his handler just enough to be brilliant and not enough to be dangerous. Then someone fell. Delgado went down hard. He didn’t yell because men like him often don’t, but his breath left him and that was worse in a way, a hole in sound that meant hurt. Duke hesitated half a second—half seconds matter. A man came out of a side office with a crowbar and swung. Delgado’s arm broke. He reached for the leash and missed. Duke went feral.

“Command gets funny when your person stops making noise,” Delgado said. His laugh had splinters in it. “We got out. But he never came back to me. I couldn’t—my doctor told me I’d be thin on my feet for a year. They pulled Duke. He treated the next two handlers like they were trespassing his grief.”

Emma didn’t speak because there was nothing to fix with sentences, and she had learned when to use silence like a gift. She stood there with the two of them and let the room be something she could not see but could feel: a chapel made of tile and memory.

“Can I sit?” Delgado asked. He lowered himself against the wall, his breath a little tight, like the pain was a stubborn tenant he had learned to live with. Duke took two steps toward him and stopped. He looked back at Emma—of course he didn’t look, but she felt the attention shift in that way her body had learned to interpret as sight. She nodded even though he couldn’t see her either, not the way a person earns permission, but the way two beings agree that trust is allowed to multiply.

Duke lay down between them like a bridge.

They began to work with a man named Miles Orozco after that—thirty-two, baseball cap, the kind of patience you only learn by failing slowly and then trying again anyway. Miles trained K‑9s and had the rare humility to admit when their bodies told him his methods were wrong. He believed in shaping behavior with reward and in letting ghosts leave the room before you teach new words.

“He needs options,” Miles said. “He needs to relearn that he can say no without losing the job.”

“What job?” Emma asked.

Miles hesitated. “The one you’re thinking,” he admitted. “If we do this, if Duke does this, it won’t be the usual path. Guide work and police work are different. Drive levels, impulse control, the whole shebang. Most retired K‑9s don’t make it. Most guide dogs start young and go through programs that are practically monk-like.”

“I don’t need a monk,” Emma said. “I need a partner.”

Miles nodded so deeply she heard the cap brim brush his neck. “Then we do it with honesty. He’s never going to be the dog people want to hug in the airport. He will always clear rooms with his nose. He will always be, in his soul, a professional.”

“Me too,” Emma said.

They began with fundamentals. “Find curb” became a game. “Left” and “right” and “forward” in a harness Duke hadn’t worn before, a guide harness with a rigid handle that transmitted information to Emma’s hand like Morse code. He didn’t like the different straps. He didn’t like the old pressure points gotten new. He lunged once when the handle creaked; Emma froze and said “Blue,” and Miles’ hand was already on the leash. Duke stopped, head down, breathing like someone embarrassed to have broken a plate at dinner.

“We’ll go slower,” Emma said into the coat of the dog she refused to be afraid of.

“Slower can be faster,” Miles said. “If we do it right.”

They practiced in the empty parking lot early enough that the birds hadn’t fully committed to their morning. Miles set down bright plastic cones Emma couldn’t see and described them anyway, and she laughed at the futility of it until he laughed too and called out distances in feet like a baseball coach. She learned to feel the tiny tilt of the handle that meant “curb” and the firm pause that meant “wait” and the living spring of a dog’s body braced against the world in such a way that both of them remained upright.

They practiced on neighborhood sidewalks when the snow was still a rumor. Duke learned to block gently when Emma drifted too close to a mailbox, to stop dead at driveways even when they were flush to the street. He started to check for traffic at intersections by cocking his head and holding his breath, which made Emma so proud she had to pretend to sneeze to hide the sound.

They practiced “intelligent disobedience”—the art of saying no when the command is wrong. It felt strange to ask for a thing and be proud when he refused. It felt familiar too. Emma had learned to tell her own body no when panic taught her to run. She cried after the first training scenario where Miles told her to go forward and Duke planted himself like a small tree.

“What’s wrong?” Dana asked later that night when she heard Emma sniff in the bathroom.

“Nothing,” Emma said, and then said everything. “He listened to himself instead of me and for once I didn’t take it personally. I think that might be the first time that’s happened and I’m not even talking about a dog.”

Dana didn’t say she was proud. She wrapped a towel around her daughter’s shoulders and squeezed once like the towel was a medal.

A month in, they walked High Street.

High Street sang differently depending on the hour. At noon it was buskers and burrito wrapper crinkles and a kind of cheerful chaos that made Emma grin. At four it was student laughter and scooters and the particular trill of the crosswalk signal that meant “watch for me.” They started at ten a.m., low traffic, the world still wiping sleep from its face.

“Ready?” Miles asked.

Emma took the harness handle. She kept the leather leash loose in her other hand, the way they’d practiced, the way that told Duke he was working and she was listening. “Forward,” she said.

They moved. It was a new sensation to trade the tap—tap—tap of the cane for the glide of a living thing reading the path before she could. Duke became sight translated into motion. He flowed around a cluster of trash cans and paused at a curb, the handle humming a small warning against her fingers. She stopped, reached with her toe for the lip of concrete like a pianist finding middle C, and smiled when it met her shoe exactly where he’d said it would be.

“Good boy,” she whispered. She wasn’t allowed to gush. Work required work tone. But praise is praise and dogs know when words are true.

They made it two blocks before the world tried to teach them too much at once.

A delivery van coughed out of the alley to their right. A cyclist sliced through space too close, the rush of air a laugh that wasn’t unkind but felt like disrespect. A siren opened its throat somewhere six streets away. Emma felt Duke’s whole body take in all of it like a calculus problem. His paws planted. He leaned back a hair. She swayed and adjusted and then the van horned an apology to nobody and the cyclist swore at himself and the siren pitched away. Duke exhaled. Emma laughed because sometimes the only answer to a city is to laugh and keep walking.

At the corner of High and Lane, they waited. The crosswalk chirped its melody and the voice said “Walk sign is on to cross High Street.” Emma listened for cars that sounded like they didn’t believe in signs. She heard one—low and quiet and wrong—an electric car fifty feet down that had rolled the right turn and was trying to be sneaky about physics. She began to step. Duke backed into her shins hard enough to bruise.

“Hey,” she said, catching her balance.

He didn’t move.

She waited. The air moved. The car slid past, consequence held in by the fact of his body braced against her. She caught the after-wash of wind and said, to him and not to him, “Thank you.” She felt the harness quiver as he took that in and recalculated the world into safe again.

Miles stood very still on the sidewalk and put his hands over his face for a second because sometimes you have to hide joy before it makes a fool of you.

“Coffee?” he said, voice steady when he took his hands down.

They sat in a café whose barista had the kind of voice that could sell anything except insincerity. Emma sipped a hot chocolate so thick it could have been a meal and listened to Duke lie under the table like a shadow that worked for a living. People asked to pet him. Emma learned to say, as kindly as she could, “He’s working right now,” and endure the small deflations that followed. Every now and then a person said, “Of course,” in a tone that sounded like they understood work and had missed it lately.

The hearing came six weeks after the first hello.

Franklin County had a risk review board that met in a room that tried very hard to look like a courtroom and didn’t quite. The chairs were too modern. The carpet attempted dignity and settled for clean. Emma sat between her mother and Miles. Duke lay at her feet, not in harness because rules but in sight—no, in place—because he had eyes and chose where to put them.

On the board: a woman who introduced herself as Ms. Shaw in a voice that suggested she had once told important men to go to hell and been right; a man with a law enforcement background who wore his badge on his plain-clothes belt because habits are anchors; a city representative who smelled like expensive raincoat.

Dr. Kincaid presented first. She used words Emma loved her for: context, mitigation, behavioral rehabilitation. She did not say “good boy,” but she could have. The city man said words Emma could taste when he spoke them: liability, precedent, optics.

“On paper,” he said, “this dog is a risk.”

“On paper,” Emma said before anyone could stop her, “I am too.”

Silence again. She had not planned to speak. She had planned to sit with her hands quiet and let adults translate her life into forms. Her mouth decided otherwise.

“Ms. Callahan,” Ms. Shaw said gently. “Would you like to be sworn in?”

Emma stood. The room did its small collective rustle. Someone brought her a Bible, then thought better of it and moved it away, then asked her to raise her right hand. She did, the calluses on her palm suddenly very interesting to her brain. She promised to tell truth, which is easier when you’ve learned lying costs more in the long run.

“I can’t see your faces,” she said, in case anyone needed to hear it again. “But I can hear your voices and I can hear the way you’re making your mouths small at me. That’s okay. I get that a lot. People think I don’t know the room because I can’t see it. I do.”

A laugh, respectful, from Ms. Shaw. A chair creak that meant discomfort from the city man.

“Duke,” Emma said, and his head lifted. She heard his collar tap against the floor like a polite cough. “Duke used to have a job. Then somebody got hurt. He didn’t fail that man. The world failed both of them. We’re asking for a different job now. Not softer. Not easier. Just different. I’m not going to ask him to be a pillow. I’m going to ask him to be my partner. He already is.”

“You’re very young,” the law enforcement man said, not unkindly.

“Yes,” Emma said. “And I’m not new at this.” She lifted her cane so they could see it even if she could not. The carbon fiber shaft had the weathering of years. “I lost my sight when I was nine. I don’t need sympathy. I need sidewalk curbs to make sense and drivers to not cheat and somebody at my side who knows the difference between ‘go’ and ‘not yet.’ He does.”

“Could you demonstrate?” Ms. Shaw asked quietly.

Miles took a breath you could land a plane on. “We can try within the limits of the room,” he said. “Obviously there’s risk.”

“There’s always risk,” Emma said, and felt her mother squeeze her knee under the table hard enough to say Girl, I know who you came from.

They set a chair in front of an open doorway to represent a curb and an alley. Miles stood ten feet away in the hall with a long leash, not attached, just there to be the emergency stop he prayed he wouldn’t need. The law enforcement man positioned himself at a diagonal like a traffic cop ready to wave.

Emma put the harness on Duke. She did it slow and sure, the buckles familiar now, the strap under his chest adjusted to where it didn’t catch his short fur. The handle lifted in her hand like a sentence half-said. She took a breath large enough for both of them and said, “Forward.”

They went forward. Two steps, three, a pause as Duke checked the doorway. She heard the almost-silent ghost of a heel scuff from the hall—someone Miles had recruited to play disrespectful traffic. Duke planted. Emma smiled without meaning to. “Good,” she said softly, and waited.

Across the hall, someone let out a long breath. Miles did not move his feet. The city man said nothing, which in Emma’s experience was a kind of progress.

The vote took ten minutes and most of a lifetime. Ms. Shaw spoke first. “Grant.” The law enforcement man said, “Grant, with conditions.” The city man said, “I will not be the obstacle here,” in a tone that made Emma like him despite herself.

The conditions were many and not cruel: weekly check-ins, continuing education with Miles, re-certification every six months, emergency plan for decompensation, handler and dog both to attend counseling with a trauma-informed therapist because grief is a third creature that sometimes lives in a leash. They signed papers. Dr. Kincaid cried in the hallway where no one could make a speech about it.

Officer Delgado waited by the door.

“If I bring him his old collar,” he said to Emma, “will you take it?”

She swallowed around a lump that was not all joy. “Only if you don’t need it.”

He laughed softly. “I need him out there loving a life.” He placed a small metal tag in her palm. It was cool, with the weight that said it had been carried. “Foxtrot Two,” he said, reading the engraved call sign. “He doesn’t need that anymore either. He’s Duke, citizen.”

Emma closed her fingers around the tag. “Thank you,” she said. She didn’t add for forgiving him by living, because some gratitude deserves privacy.

They built a life the way you knit a sweater: one row of days at a time, some days dropped stitches, some perfect. Duke learned her routes—to the bus stop, to the choir room, to the little bakery that piped the smell of cinnamon onto the sidewalk like a public service. He learned the grocery store’s absurd floor plan, the way the freezer aisle made his paws slip and how to slow down through it without losing purpose. Emma learned how much of her body lived in her hand—the harness transmitting his decisions into her bones so she could call them hers aloud.

At school, teachers adjusted. The vice-principal sent an email that made Emma brace until she read it and found it was full of competence: procedures for animals on campus, reminders to students not to distract, a paragraph that was as much about respect as policy. Most kids obeyed. A few tried to test the boundaries because adolescence often wants to be the exception to rules. A boy named Tanner snapped his fingers and said, “Hey, dog,” in a tone that made the word sound like a dare. Duke ignored him the way professionals ignore noise.

“Sorry,” Tanner said later, properly chastened. Emma chose to believe he meant it. It’s easier to walk hallways when you believe people can be taught.

Her friend Caleb Brooks started walking with them after his last-period chemistry lab. He was long-legged and careful with language, a combination Emma found restful. He narrated the world when she asked him to and shut up when silence was better. He described the stupid sweatshirt the math team had made that year—“a parabola with sunglasses”—and the Christmas lights the custodian had looped in the atrium. She held those images like little stones in her pocket, not because she missed light, though sometimes she did, but because it felt good to be included in surface-level beauty.

“Prom?” he said one afternoon in April, casual with an edge of fear.

Emma laughed. “We’re sixteen.”

“Right,” he said, as if he had been testing a different question entirely. “Spring concert then.”

“Spring concert,” she agreed.

On a bland Thursday that had forgotten how to be interesting, Emma woke to rain spelling Morse on the window. Dana texted from the early shift: Be careful. Slow feet. She added a heart emoji because technology makes love visible in ways letters never could. Emma dressed in the order that kept memory steady: jeans, socks, boots, sweatshirt, jacket. She clipped Duke’s harness and ran her fingers along the straps the way you check an airplane seat belt before takeoff.

They took the bus. Duke found the door frame with his shoulder and kept Emma from banging a knee on the fare box. The driver said, “Good morning, ma’am,” in a voice that sounded like her grandfather’s when he was trying to sell a point, and Emma liked him immediately. The bus smelled like wet people and old coins. They sat, front left. Duke curved his body and made room for her feet.

Halfway to school, the bus lurched. Not the ordinary lurch. A new kind, a sharpness in motion that meant a human mistake. Someone in a truck had decided red lights were for other people. There was the shriek of brakes and a chorus of gasps and then the sound of two vehicles performing intimate physics. The bus tilted like a boat in hard water. Emma grabbed the pole. Duke braced, his body turning into a question mark that held her up.

“Everybody okay?” the driver asked, and the choir of voices did what choirs do: answered in a chord that was messy but meaningful.

Emma was okay. A toddler two seats back was not. She heard the fearful hiccup in the child’s breathing—the inhale that didn’t know how to turn into exhale because panic had stolen grammar. The mother’s voice climbed into panic to try to reach him and failed because panic can’t translate itself.

“May I?” Emma asked, already standing, Duke pressed to her shin.

“Please,” the mother said, and Emma felt small, damp hands thrust toward her in the kind of desperate trust that makes strangers family for a minute.

Emma lowered her voice to the tone she used with Duke when the world got loud. “Hey, buddy,” she said. “Listen to this. Breathe like a snake.” She hissed. “In. Out. Good. You’re okay.” She did not touch his face. She rested her knuckles on the back of his small hand. The little boy copied her hiss. The mother’s breath steadied. The bus settled into the physics of after.

“Thank you,” the driver said to no one in particular and to all the particular someones who had helped.

Duke guided Emma off twenty minutes later when EMS had cleared them. He curved around a piece of plastic that had fallen in the aisle like it was a wall. He paused at the top of the bus steps and took the measure of the curb and the rain and the world and signaled in a way her fingers read as we can do this.

School conducted itself as if nothing had happened because sometimes institutions believe themselves immune to stories. The spring concert practice ran long. Emma sat in the second row of the alto section and turned her face toward the conductor’s voice, then down toward the printed words she would never read in ink but had memorized from the audio file: “Bridge Over Troubled Water” and a medley that made the audience feel better about the decade of the songs.

The fire started the way fires start, which is to say nobody meant it and everybody blamed themselves twice as much as they deserved to. A cheap extension cord overheated backstage. Plastic decided to melt. One spark found a witness. The smoke alarm did what smoke alarms do—the most irritating, necessary cry in the building. The choir director had practiced this a hundred times. He said, “Walk, do not run,” in a voice that earned obedience from most and panic from a few.

The atrium filled with sound that had weight. Feet. Metal chairs scraping. The bright alarm making a joke of all their voices. Emma stood. Duke was already up, body taut in a way that didn’t mean fear. It meant math. He mapped exits, people, the smell of smoke that wasn’t yet dangerous and needed to be treated like it might be anyway.

“Forward,” Emma said. They moved.

The main door jammed because doors do that when everybody wants them. Someone pushed. Someone yelped. The press of bodies became a force. Duke veered left. Emma went with him because the harness told her sense to choose him over the line. He guided her toward the side door she’d never used. He slowed for a girl sobbing into her hands and slid his body between Emma and a boy who wasn’t watching where his backpack swung. The side door opened. Air changed. People spilled onto the sidewalk like a poured drink.

Emma heard a child wailing—a sound too high, too ragged. She froze a heartbeat before the harness tugged. Duke pulled right, not hard, but with the insistence that means I know a thing. He led her behind the crowd control fence and into the thin slice of space by the building where two maintenance workers had propped a window weeks earlier and never fixed the lock. Smoke coughed out of it. The crying lived just inside.

“Hello?” Emma said, and the crying hiccuped, a tiny voice behind it.

“It’s okay,” Emma said, hand out, the heat a scratch on her skin, not a burn. “I’m here.”

“Ma’am,” one of the maintenance men shouted from the yard. “What are you doing?”

“Getting a kid,” she said. “Can you keep yelling so I know where to hand them?”

Duke planted. He took in the world through his nose and told her the story. She crouched, put her hand through the window, and felt the soft cotton of a hoodie sleeve. Small fingers grabbed hers with unambiguous authority.

“You’re brave,” she said to the small whatever of a person at the other end of her hand. “Come on now.” She pulled, gently. The kid wriggled, got a knee on the sill, and then hands from outside took shoulders and pulled. A little body landed into a lot of safety.

“Got her!” someone yelled.

Emma backpedaled, catching her balance with one hand on Duke’s harness. They were still in the stupid wedge of space behind the fence. The easy way back to the sidewalk was blocked by panicking teenagers and a band director having an existential debate with a trombone. Duke offered her the longer way: down the narrow path to the maintenance gate and out to the parking lot.

They emerged into air that tasted like overcooked toast and victory. Somebody clapped because human beings love to clap when they don’t know what to do with relief. Someone else cried for exactly sixteen seconds and then stopped as if a timer had gone off. The little girl’s mother found her with a sound that broke the day into before and after.

“Thank you,” the principal said later, after the fire department cleared the building and determined the school still existed. “How did you—?”

“Duke,” Emma said. She didn’t add I followed the dog because the truth was she had followed the life she’d chosen and the training they’d done and the way the harness told the story her eyes could not.

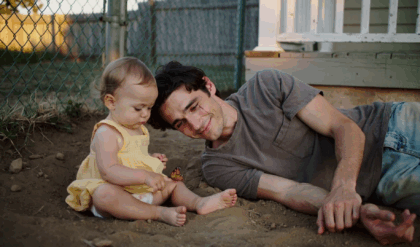

The local paper wanted a picture. They asked if Duke could take his harness off for the shot because they wanted to see “his face.” Emma said yes for the first time since he’d begun working because sometimes showing the tenderness behind the job works better than insisting on the job itself. Duke put his head in her lap and let a photographer with a kind voice find their angle. The story ran under a headline that made Emma wince—BLIND STUDENT AND RETIRED K‑9 SAVE LITTLE GIRL—but the article was kind, and accurate where it mattered, and the comments section surprised Dana by being mostly full of gratitude instead of small cruelties.

Officer Delgado dropped by that weekend with a bag of tennis balls and a pizza that made the house smell like summer baseball games. He didn’t say much. He never did. He sat on the Callahans’ porch and listened to Duke wolf down a slice of pepperoni in four bites and then pretended not to throw the tennis ball when the dog watched too closely.

“He’s good,” Delgado said at last.

“He’s mine,” Emma said, and the word had the taste of wonder she hoped would never leave.

Dana leaned in the doorway, arms folded, mouth soft. She didn’t say the thing mothers are supposed to say about dogs not being people. She said, “You’re both better for it,” and then called, “Who wants ice cream?” because life goes on.

Not everything was cinematic.

There were days when Duke woke with old nightmares and paced for twenty minutes before he came back into the room. There were nights when Emma lay awake rehearsing how she would handle him if he redirected and hurt her, the same way she’d rehearsed tornado drills when she was eight and could see the pictures on the classroom wall. There were rainy mornings when his refusal to get on the bus because of a smell she couldn’t smell made her late to algebra and she cried in the bathroom because being late to algebra feels like the end of the world when you’re a junior.

They saw a therapist together the board required, a woman named Dr. Yu with a voice like a library. She taught Emma to notice the difference between the dog’s fear and her own and to let both be true without letting either drive. She taught Duke to turn when he heard a noise behind him instead of spinning toward it like a storm.

“Grief is a third thing,” Dr. Yu said. “It will try to walk you. You’re allowed to put it on a leash.”

Emma loved her for that. She wrote it on an index card in Braille and kept it in her pocket under the tag that still said Foxtrot Two.

In June, two blocks from the Kroger on Chambers Road, a man grabbed Emma’s wrist.

She wasn’t being reckless. She wasn’t wearing headphones or walking alone at midnight or any of the things people use to blame victims for existing. It was noon. She stopped at a corner to wait for the light. A man stepped up too close and said, “Hey, sweetheart.” His breath smelled like cheap beer layered over older bad decisions. She shifted away, Duke braced, the harness vibrating warning.

The man grabbed her anyway, fingers closing on the thin bones above her glove. “Where you going in such a hurry?”

“Let go,” she said. Her voice came out steady because practice does that. Her heart wrote a fast letter to her lungs.

He laughed. It wasn’t the laugh of real humor. It was the laugh men do when they want to teach you that they can.

Duke moved in a line that was not a lunge. He placed his body between Emma and the man’s center of balance the way Miles had shown them in a controlled setting. He didn’t bite. He didn’t growl. He pressed forward, not hard enough to knock the man down, hard enough to make the man step back and release her wrist. When the man lifted his hand again, Duke showed teeth. Not an accident. Not a snarl. A statement: boundary.

“Whoa,” the man said, stumbling a step. “Okay.” He raised his palms. His voice picked up the false cheer of someone trying to reframe a mistake. He backed off, muttering something that didn’t matter. Duke didn’t chase. He turned his head and found Emma’s knee with his muzzle like a question.

“I’m okay,” she said, when she made sure it was true.

A woman from the bus stop said, “I saw that,” in the tone of a sworn statement. “You did good, dog. You did good, sweetheart.”

Emma walked home slower. She stood in the kitchen while Dana clenched the counter so hard her knuckles looked like they might leave dents. “I’m okay,” Emma said again.

“I know,” Dana said, and then, “I hate that you have to be.” She kissed the top of Emma’s head like she had when Emma was five and had scraped her knee chasing a kite.

Summer unspooled. They went to the farmer’s market and learned to navigate children with balloons. They visited Delgado’s precinct for a cookout and listened to stories told from folding chairs, the ones cops tell each other as if they’re talking about fishing but they’re really keeping each other alive a little longer by naming the things that could have gone the other way. Duke wagged and did not cower when someone dropped a metal tray; he looked to Emma, who said “It’s fine,” and he believed her.

On the Fourth of July, they stood at the end of a neighborhood street and listened to fireworks like a city cracking its knuckles. Duke’s body turned to noise the way a radio does when a station goes bad. Emma counted. She petted his chest instead of his head because Miles said it told dogs the truth about where their hearts were. She put her mouth to his ear and said, like prayer, “You see for me and I’ll believe for you.” He sat on her foot and became weight and warmth and the idea of home.

In August, Officer Delgado asked if he could walk them down to the river. “I want to show you something,” he said, and embarrassment made the words scratch.

He took them to a small bridge over a narrow piece of water that thought very highly of itself. On the rail: a brassy plaque that had been there all along. Emma’s fingers found it first, reading the raised letters the way she read everything now—by touch. The plaque said: IN HONOR OF K‑9 DUKE, WHO SERVED THE CITY WITH COURAGE AND FOUND HIS WAY HOME.

Emma laughed the kind of laugh that pulls tears up with it. “He can’t read,” she said.

Delgado coughed a smile. “You can.”

They stood there a long time. People passed and made space without being asked. August heat stuck to their necks and didn’t matter. Emma slid the old Foxtrot Two tag next to the new letters, the metal clicking like a handshake. Then she closed her hand on the tag again because some things you keep.

Senior year started. College brochures arrived speaking fluent optimism. People asked Emma what she wanted to study. She wanted to say something impressive to make it easier for them to be proud of her. She said the truth instead.

“I want to study music and psychology,” she said. “I want to learn the science of the sounds that saved me.”

“What saved you?” her guidance counselor asked, not rudely.

“Listening,” she said. “And a dog.”

She applied to schools that had programs willing to accommodate a student plus a working dog. The applications had boxes you checked for disability, which felt like a trick and also like a kindness. She wrote about Duke in one essay and about the day she realized she belonged to herself in another because admissions committees should learn about both.

In October, a new volunteer at the shelter decided rules were for other people and tried to take a selfie with Duke without asking. Duke turned his head away like a professional dodging paparazzi. Emma said, “Please don’t,” in a voice that made Dr. Kincaid look over and put a hand to her heart because the girl who had asked to just talk months ago now held boundaries with the ease of a veteran.

“Sorry,” the volunteer said, meaning it.

“Thank you,” Emma said, meaning it too.

They went back to the hearing room at six months for re-certification. Ms. Shaw had retired, the city man had been replaced by someone whose perfume announced wealth, and the law enforcement man had grown a beard that made him look kind. None of that mattered. The room had learned them. They walked another little maze, answered questions about protocols, submitted logs that showed fewer and fewer incidents of anxiety. The board stamped APPROVED on a form loud enough for Emma to hear it. Papers have sounds when the stakes are high.

On the way out, a janitor said, “Is that the dog from the paper?”

“Yes,” Emma said, and then, because she loved tellings that set things right, “He’s Duke.”

Winter came the way Ohio winter always comes: slowly until suddenly. The sidewalk corners iced like a stupid joke. Duke learned to press against Emma’s thigh a fraction harder on slick mornings so her foot would find purchase before commitment. She learned to carry a small bag of crushed nuts for mornings when courage is a blood sugar problem. They learned to love the same blue wool beanie.

On a night in January when the world looked like a cinched hood and sounded like a house sighing, Emma dreamed. She dreamed of light not as pictures but as feeling. She dreamed of Duke leading her down a hallway with no walls, her hand light on the harness, the floor soft like fresh bread, and at the end of the hall a door that opened by itself because it knew they were coming.

She woke with the taste of new in her mouth and laughed alone in the dark because sometimes joy arrives with no witnesses and that doesn’t make it smaller.

Graduation happened under a sky so bright that even the sighted squinted. The principal called names. When he reached “Emma Grace Callahan,” the crowd stood. Not because pity. Because community knows who did the work. Duke walked at her side, the tassel on her cap (she wore it because you wear it) bumping her eyebrow in a way that made her grin. She paused, hands feeling for the edges of the stage the way a person finds the edges of a new truth. The vice-principal offered an elbow and she took it because help given well is a kind of music too.

At the after-party in the church basement that smelled like sheet cake and folding chairs, a freshman came up to her and said, “My brother has autism. He loves dogs. Do you think…” He didn’t finish because asking for things out loud is sometimes the hardest part.

Emma knelt so she wouldn’t tower over him. “I think love fits in a lot of places,” she said. “Tell him hi from me.”

In the corner, Officer Delgado stood with his hands shoved in his pockets, watching two people he loved more than he thought he ever would learn how to be celebrated without apology. He caught Dana’s eye. She lifted a paper cup of lemonade in salute. He lifted his in return. The world was quiet for a second that stretched like good taffy.

That night, when the house was still, Emma lay on her side and curled her hand under Duke’s ear. He made the tiny old-man groan that had nothing to do with age and everything to do with contentment.

“You see for me,” she whispered. “I’ll believe for you.”

This was the part no one had prepared her for: the way partnership grows into a language you speak without words. The way grief becomes a relic you tuck behind the plaque on a bridge. The way you can love a creature who once scared you because they taught you how to be brave in your own body.

In the morning, the city would be — as always — an orchestra tuning up. Buses would wheeze. Bells would throw their notes over water. Somewhere, a person would be afraid to ask and then ask anyway. Somewhere, a dog would decide not to bite history and to trust a hand instead. Emma would wake, clip a harness whose leather had softened with use, and step into a world that had learned her shape. Duke would stand, shake the night off his shoulders, and tilt his head toward the door like a man tipping his hat. They would go, not because stories demand forward motion, but because life does.

They had met like two lost souls in a hallway of metal and caution tape. They had walked out like a sentence finished by the right word. They kept going because love, when it is work and choice and something you keep choosing, becomes a way to see.