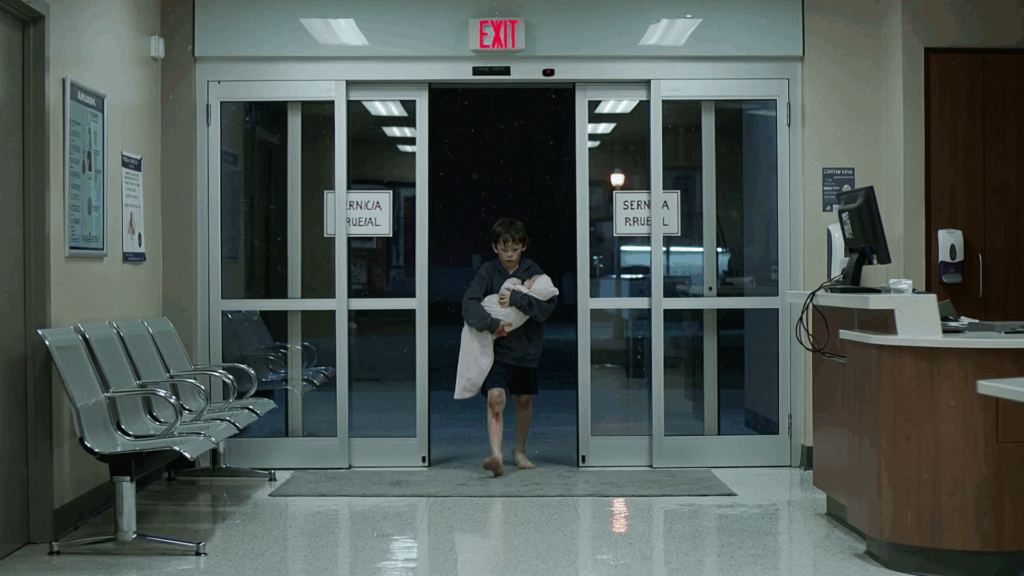

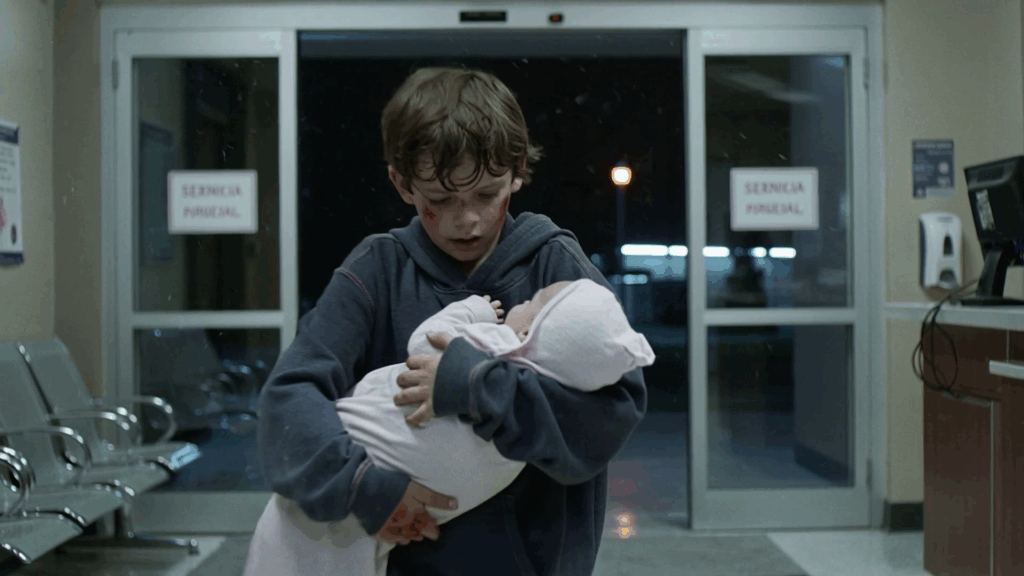

It was just past midnight when Ethan Walker, a bruised seven-year-old boy, stumbled into the emergency room of St. Mary’s Hospital in Indiana, carrying his baby sister wrapped in a thin pink blanket. The automatic doors slid open with a soft hiss, letting in the freezing winter air—and a silence that made every nurse look up. A night nurse named Caroline Reyes was the first to notice. Her eyes widened as she saw the small boy, barefoot, his lips trembling from the cold. He clutched the baby so tightly it looked like he was holding on for life itself.

“Sweetheart, are you okay? Where are your parents?” she asked gently, moving closer. Ethan swallowed hard. His voice came out as a hoarse whisper. “I—I need help,” he said. “Please. My sister’s hungry. And… we can’t go home.”

Caroline’s heart sank. She immediately led him to a nearby chair. The fluorescent lights revealed the truth: purple bruises on his arms, a cut near his eyebrow, and dark fingerprints visible even through his worn sweatshirt. The baby, maybe ten months old, stirred weakly in his arms. “Okay, honey, you’re safe now,” Caroline said softly. “Can you tell me your name?”

“Ethan,” he murmured. “And this is Lily.”

Within minutes, a doctor and security guard arrived. As they guided Ethan to a private room, the boy flinched at every sudden sound. When a doctor reached out to examine him, he instinctively shielded his sister. “Please don’t take her away,” he begged. “She gets scared when I’m not there.”

Dr. Alan Pierce, the attending pediatrician, crouched down to his level. “Nobody’s taking her, Ethan. But I need to know—what happened to you?” Ethan hesitated, eyes darting toward the door as if afraid someone might burst in. “It’s my stepdad,” he whispered finally. “He hits me when Mom’s sleeping. Tonight he got mad at Lily for crying. He said he’d make her stop forever. So… I had to run.”

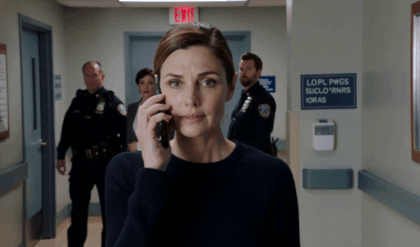

Caroline froze. Dr. Pierce exchanged a grave look with the security guard. Without another word, he called for the on-duty social worker and the police. Outside, the storm raged, snow piling on the hospital steps. Inside, the small boy who had risked everything sat trembling, clutching his sister close, unaware that his words had just set in motion a chain of events that would change both their lives forever.

Detective Mark Holloway arrived within the hour, his face grim beneath the hospital’s sterile lights. He had handled dozens of child abuse cases—but few began with a seven-year-old who had the courage to walk through a blizzard for help. Ethan sat quietly in the consultation room, Lily now asleep in a blanket the nurses had given her. The boy’s small hands trembled as he answered the detective’s questions. “What’s your stepfather’s name, Ethan?” “Rick Mason.” “Do you know where he is right now?” “At home… he was drinking when we left.”

Detective Holloway nodded to Officer Tanya West, who immediately began coordinating with local units. “Get a team over to that address now. Quiet entry, possible child endangerment suspect.” Dr. Pierce treated Ethan’s injuries—old bruises, cracked ribs, and marks consistent with repeated abuse. Meanwhile, social worker Dana Collins comforted him. “You did the right thing by coming here,” she told him. “You’re very brave.”

At 3:00 a.m., police arrived at the Walkers’ small house on Elmwood Avenue. The lights were still on. Through the frosted windows, officers could see a man pacing, shouting into the void. The floor was littered with beer cans. As soon as they knocked, the yelling stopped. “Rick Mason!” an officer shouted. “Police department—open up!” No response. Seconds later, the door burst open. Rick lunged at the officers with a broken bottle, screaming. Within moments, he was restrained and cuffed. The living room told its own story—holes punched in the walls, a broken crib, a bloodstained belt draped across a chair. When Holloway got the call confirming the arrest, he exhaled for the first time that night. “We got him,” he told Dana. “He won’t hurt anyone again.”

Ethan was sitting quietly, holding Lily, when they told him. He didn’t smile—just looked relieved. “Can we stay here tonight?” he asked softly. “It’s warm here.” “You can stay as long as you need,” Dana promised. That night, as snow fell outside, the hospital room became a refuge—one where the world finally began to feel safe again.

Weeks later, the initial hearing began. The evidence was overwhelming—Ethan’s testimony, medical reports, and the physical proof from the house. Rick Mason pled not guilty at first, then folded when the photographs and the EMT reports hit the record; his public defender advised him to take responsibility. Ethan and Lily were temporarily placed in the care of a foster family, Michael and Sarah Jennings, who lived just a few miles from the hospital. For the first time, Ethan slept through the night without fear of footsteps in the hallway. Sarah enrolled him in a nearby elementary school, while Lily started daycare. Slowly, Ethan began to rediscover what it meant to be a child—riding a bike, laughing at cartoons, learning to trust again. But he never let Lily out of his sight for long.

The Jennings house sat on a quiet cul-de-sac where mailboxes wore winter hats knitted by a neighbor everyone called Grandma Iris. Michael was a high school history teacher who made grilled cheese exactly the same way every Saturday—heavy on the butter, crispy at the edges—and he liked to tell Ethan useless facts at the kitchen island. “You know, buddy,” he’d say, flipping a sandwich, “the first traffic light in America was installed in Cleveland, 1914.” Ethan would nod like a polite adult and spoon applesauce into Lily’s mouth. Sarah, who ran a home bakery out of the detached garage, always smelled faintly of cinnamon and soap. She kept Lily on her hip like she’d been born doing it and learned the way Ethan liked his hot chocolate—two marshmallows, not three, because three felt like showing off.

The first nightmare came in February, a month after the hospital. Sarah woke to the sound of Ethan whispering at the foot of her bed. “I can’t find Lily,” he said, but Lily was asleep in the nursery down the hall, nightlight glowing. Sarah walked him there and let him sit on the rug, listening to his sister breathe. When he finally crawled into bed, he did it at the foot of her bed like a cat, hands under his chin. In the morning he apologized for the trouble. “Not trouble,” Sarah said, and meant it.

At school, Mrs. Dalton—the sort of second-grade teacher who wore themed earrings and carried glue sticks like a gunslinger—gave Ethan a classroom job: tending the class plant, a droopy pothos that perked up under his care. The first time he brought home a spelling test with a gold star, he tucked it under the sugar jar in the kitchen and didn’t tell anyone. Michael found it when he reached for his coffee. “This yours?” he asked, and Ethan nodded, bracing for the way pride sometimes turned into anger in his old life. Michael only grinned. “Looks like we’ve got a botanist and a word wrangler,” he said, then taped the paper to the fridge with a magnet shaped like the state of Indiana.

Detective Holloway kept in touch. He’d stop by on Saturday afternoons in his Notre Dame hoodie, carrying a bag of donuts and updates that were careful but honest. “He’s not coming back,” he said, meaning Rick. “We’ve got your statements on the record, and the DA is pushing for the maximum.” Ethan didn’t ask the question Holloway could feel vibrating in the air: What about Mom?

Rachel Walker had been beautiful in a way that made small-town cashiers forgive her late fees. She worked part-time at a salon on Highway 31 and full-time at trying to outrun the truth. When she came to the first hearing, she wore a coat that didn’t fit and a lipstick that did. She sat on the wrong side of the courtroom, behind the defense table, as if love were magnetic and she couldn’t help where she stuck. When the judge asked if she had anything to say about the petition to remove Ethan and Lily from her custody pending trial, Rachel looked down and said, “I want them safe,” as if safety were something that happened to other people.

Afterward, in the corridor polished to a shine by too many tired feet, Rachel approached Dana Collins. “Can I see them?” she asked. Dana considered the court order and the schedule. “We can arrange a supervised visit,” she said. Rachel nodded, then shook her head. “Not yet,” she whispered. “I don’t want them to see me like this.”

The first supervised visit finally happened in March in a room at the county building that tried too hard, a space painted lemon with a plastic play kitchen and a stuffed giraffe missing an ear. Ethan arrived holding Lily’s hand. Sarah carried the diaper bag and the quiet hope that the day would be gentle. Rachel was already there, twisting a napkin into a rope. When Ethan saw her, he froze. Rachel stood. “Hey, bug,” she said, voice shaking. She didn’t reach for him. It was something. “I brought you something.” She offered a book with a bent corner—“Charlotte’s Web,” the same edition Rachel had read at eight, her name penciled on the inside cover in a child’s careful print. Ethan took it, touched the corner, and nodded. Lily reached for Rachel’s necklace; Rachel let her grab it and didn’t flinch when it snapped. “It’s okay,” she said, half-laughing, half-crying. “It was from the store at the mall. Two for ten.”

Dana watched the way Ethan kept half an eye on the door. She watched the way Rachel kept glancing at the window as if someone were coming. She made notes a judge would read, then set the clipboard down and became a person again. “You want to hold your daughter?” she asked. Rachel nodded and sat with Lily asleep against her chest, the weight of consequence heavier than the baby.

In April, the DA took a plea. Rick Mason, facing a stack of charges and not a lot of charm, agreed to fifteen years. It was a number that made some people nod and others grind their teeth. For Ethan, it was an end date that lived far away, behind so many birthdays it became a number that meant “not today.” When Dana told him, he didn’t celebrate. He asked if the judge could make it so Rick didn’t know where they lived. “He won’t,” Dana promised. “He doesn’t get to know anything about your life anymore.”

Spring rolled across Indiana like a soft-serve cone, messy and sweet. The Jennings took the kids to the park near the high school where the running track wrapped around a patch of grass full of dandelions. Michael taught Ethan to throw a baseball, not with the bored half attention of a man who’d rather be on his phone, but with the kind of focus that says, I will be exactly where you need me to be. “Don’t aim your arm,” he said. “Aim your eyes.” Ethan threw, missed, threw again. Lily toddled after the ball, hair fluffing in the wind like a baby chick.

On Memorial Day, the town lined Main Street with folding chairs and kids on scooters, waiting for the parade. The high school band marched past, a little off-key, and the VFW guys tossed butterscotch candies that skittered underfoot. Caroline Reyes waved from the hospital float, a banner that said THANK YOU, NIGHT SHIFT! flapping in the sun. When she saw Ethan on the curb, she hopped off and hugged him, whispered, “You look taller,” as if being taller were a plan come true. Ethan introduced her to Michael and Sarah. “This is my friend Caroline,” he said, choosing the word carefully. Lily grabbed Caroline’s badge and tried to chew it. “Occupational hazard,” Caroline said, laughing.

That evening, after the kids were asleep, Michael and Sarah sat at the dining room table with Dana Collins, forms spread like a paper garden. “We’d like to be considered for adoption,” Michael said, feeling like the words were both too big and not enough. “If that becomes part of the plan.” Dana nodded. “We’ll begin the concurrent planning paperwork,” she said. “Ethan’s mother has a case plan—sobriety, counseling, stable housing, domestic violence classes. If she works it, we support reunification. If she doesn’t, we plan for permanency with you.” Sarah folded her hands. “We’ll keep cheering for her,” she said, and meant it, even though the thought of letting go made her throat ache.

Rachel tried. For two months she tried hard enough to make her knuckles go white. She moved into a women’s shelter that smelled like powdered eggs and hope. She went to meetings in a church basement where the coffee was terrible and the chairs were metal, and she told the truth out loud—the way Rick’s anger had shrunk her world, the way she’d traded the voice inside her head for the one that said, “Don’t make him mad.” She got a job at a diner off the highway and learned how to hold three plates in one hand. She sat in group therapy and said her name when it was her turn. “I’m Rachel,” she whispered, and the circle answered, “Hi, Rachel,” like a benediction.

Then July arrived with heat that glued clothes to skin, and Rachel missed two visits. The third week she didn’t call at all. Dana drove to the shelter; Rachel’s bed was empty. A staffer with kind eyes said, “She left with a man.” Dana closed her eyes for a moment and pressed her fingers to her temple. The judge issued a bench order for a protective review and, quietly, a warrant on an old failure-to-appear charge related to a traffic ticket that no one had the bandwidth to care about until now. It wasn’t the kind of warrant that made headlines. It was the kind that made social workers rework plans on a Friday afternoon.

Ethan didn’t ask where Rachel was. He learned how not to ask in the years when asking made everything worse. But he carried the book everywhere, “Charlotte’s Web,” like proof that some part of his mother was real and gentle and wanted him to have something that lasted. One night in August, he placed it in Sarah’s lap. “Will you read it to me?” he asked. Sarah turned to the first page and did the voices, even Templeton the rat. When she got to the part where Charlotte’s babies drifted away, her voice snagged. Ethan didn’t notice. He was watching the way the words built a world where a pig could be saved by a spider and a friend.

School started again, and with it came the small rituals of normal life that feel like miracles when you haven’t had them. Back-to-school night, where Michael stood by the classroom hamster cage and introduced himself to Mrs. Dalton as “Ethan’s person for now.” He didn’t say father. He let the word hover like a bird that might land if everyone stayed very still. The first soccer game on a field that tilted a little to the left; Sarah clapped for both teams and packed orange slices in a cooler with a squeaky handle. Lily learned the word “more” and used it for everything—the swing at the park, blueberries, hugs.

In October, Detective Holloway called with an invitation. “We’re doing a family day at the precinct,” he said. “Games, hot dogs, that sort of thing. You want to bring the kids? Lots of officers who’ve been following the case would like to meet the hero.” Ethan flushed when Sarah told him. “I didn’t do anything,” he said. “I just walked.”

At the precinct, Officer Tanya West set up a little obstacle course with cones and a plastic tunnel. “You think you can beat my time?” she asked, dropping to one knee to look Ethan in the eye. Ethan considered the tunnel, the way dark spaces still pulled at old panic, and lifted his chin. “I think I can beat my time,” he said. He crawled through, heart thumping, and came out the other side to the sound of strangers cheering his name like he’d scored a goal in a stadium.

By Thanksgiving, the Jennings had a photo on the mantle of four people and a dog they’d started fostering the same week they started thinking about forever. The dog was a senior mutt named Rufus with eyebrows so expressive he looked like someone’s fussy uncle. Rufus adored Lily and tolerated everybody else. When the turkey came out of the oven, Rufus positioned himself like security. “He’s our quality control,” Michael said. They went around the table and said what they were grateful for. Ethan said, “Lily’s laugh.” Sarah said, “Found family.” Michael said, “Second chances.” Lily said, “Dog.” Everyone agreed it covered it.

In December, a year after the night of the blizzard, the adoption petition landed in a stack on Judge Karen McPhee’s desk. The judge read every word. She’d been a public defender once, then a prosecutor, and she didn’t trust easy. She called Dana to chambers. “Tell me why this is right,” she said, not because she didn’t see it, but because gravity requires words. Dana talked about bedtime and soccer fields and hot chocolate math. She talked about nightmares and the slow return of sleep. She talked about Rachel, too, and the empty space where a mother should be. “We will keep the door open for contact,” Dana said. “If it’s safe. If she shows up. But Ethan needs permanence.” Judge McPhee nodded. She set a date in January. In the Jennings kitchen, Michael circled it on the calendar in blue pen and drew a star. Ethan watched him and asked, careful as ever, “Does the judge know I still want to see my mom if it’s not scary?” Michael put the cap back on the pen. “She knows,” he said. “Because you told her with your whole life.”

The night before the hearing, a storm rolled in. Indiana loves its symmetry. The wind tossed ice like rice at a wedding, and the world went quiet under white. Sarah laid out Ethan’s shirt and little tie, and a dress with a hem Lily would step on. Michael polished his shoes and realized halfway through that he was crying. He left one shoe shined and the other still scuffed and sat on the edge of the tub until the wave passed. Sarah found him there and leaned her head on his shoulder. “Me too,” she said.

They arrived at the courthouse early. The hall smelled faintly of lemon cleaner and coffee. Caroline was there, having taken the morning off, her scrubs under a wool coat, a thermos in her hand like she arrived for rounds. Dr. Pierce came, too, with a knit scarf that made him look like someone who owned a cabin and wrote letters. Holloway and Tanya posted up by the elevator like polite bodyguards, though there was no one to guard against. Dana checked the file for the fifth time and handed Ethan a pen. “You’ll sign with this,” she said, and Ethan held it as if it could weigh a hundred pounds or nothing at all.

The hearing was not cinematic. There were no violins, no gasps, just the small strange holiness of bureaucratic mercy. The judge asked Ethan if he understood, in a seven-year-old way, what it meant to be adopted. Ethan said it meant he would live where Lily lived. The courtroom laughed, softly. The judge asked if anyone objected. No one did. She signed her name in a sweep that turned ink into future. “Congratulations,” she said, and banged the gavel not because she had to but because joy deserves a sound.

Afterward, in the hallway, they took a photograph. It caught Ethan mid-blink and Lily mid-squirm and Sarah mid-tear and Michael mid-laugh. Rufus wasn’t allowed in the courthouse but somehow he ended up in the picture anyway when Michael later taped a snapshot of the dog to the corner of the frame. “Family,” he wrote in blue pen.

That night, they celebrated with pancakes for dinner. Sarah burned the first batch because emotions aren’t a condiment you can set aside. Ethan flipped the second one perfectly and bowed like a chef on TV. Lily clapped, syrup on her cheeks. Michael put the adoption certificate on the fridge under the Indiana magnet, next to the spelling test, and thought about how paper could hold the outline of a life if everyone agreed to believe in it. He sat at the table with Ethan afterward and opened “Charlotte’s Web.” “You want to finish it?” he asked. “We can start over,” Ethan said, and Michael understood the theology of that sentence.

Spring came again, because it does. Lily learned to say “Eee-fan,” which made Ethan laugh until he fell over. Rufus forgot which stairs were hard and would stand at the top looking insulted until someone carried him down. Caroline visited on Sundays sometimes and let Ethan hold her stethoscope to hear his own heartbeat. “Sounds strong,” she’d say. He would nod like a person taking a compliment and add, “It’s faster when I run.”

One afternoon in May, Rachel appeared on the sidewalk across the street. She didn’t come closer. She wore a denim jacket and a face that had lost some of its blur. Sarah saw her through the window and went to the door alone. Rachel lifted a hand. “I’m sober,” she said, voice even. Sarah nodded. “That’s good.” Rachel swallowed. “I’m not here to take anything,” she said. “I just wanted to see if they looked happy.” Sarah could have said a hundred things—about timing, about pain, about the way healing for one person sometimes reopens a stitch for another. She said, “They’re okay.” Rachel looked down at her hands. “Tell Ethan I read the part with the web again,” she said. “It still works.” Sarah thought of a spider who saved a pig and the words that made it true. “I’ll tell him,” she said. Rachel nodded once, like payment received, and walked away.

Ethan asked that night if spiders were scary because they had to be to survive. Michael said no, that maybe the trick was learning how to be strong without becoming dangerous. Ethan considered that for a while. “Like us,” he said finally. “Like us,” Michael agreed.

On the first day of summer, the neighborhood held a block party—the kind with paper plates bending under potato salad, kids drawing with chalk, and a man in a straw hat who insisted on singing old country songs until someone bribed him to stop. Ethan joined a water balloon fight organized with military precision by Tanya West and lost on purpose twice so the little kids wouldn’t cry. Lily danced in circles until she fell over. Sarah passed around lemon bars and listened to the way people say “our” when they mean it. Caroline brought a first aid kit and never had to open it. Dana showed up late from another case, hair frizzed by the heat, and looked at Ethan with the quiet satisfaction of a person whose job sometimes gets to finish something. “You okay?” she asked. Ethan nodded. “I’m good,” he said, and Dana let the sentence stand without adding, for now.

Later, when the fireflies came out, Michael lay on the grass with Ethan and tried to catch them by pretending not to care. “They like patience,” he said. “They like gentleness.” Ethan held out his hand and one landed, a little lantern trusting a palm. “You think Lily will remember any of the old stuff?” he asked, not looking up. Michael thought about memory and mercy and the way brains protect small people. “She’ll remember what we tell her and what her body keeps,” he said. “We’ll help the story make sense.” Ethan nodded like a man who had signed a contract. “Okay,” he said. “We’ll tell her the good parts louder.”

Years later, a teacher would ask Ethan to write about a hero. He would write about a nurse who said sweetheart and a doctor who made his voice quiet. He would write about a detective who brought donuts and stayed. He would write about a woman who made cookies and a man who learned to shine shoes, and a baby who taught everyone how to laugh like a bell. He would write, in the last line, about a boy who walked through a storm because he thought he was small and discovered he was bigger than the night.

But for now there was just a backyard, and a dog with eyebrows, and a sister asleep on a blanket, and the sound of summer in a town that had made room. The world had not become perfect. It rarely does. It had become enough. And in the quiet that followed the long year, enough was everything.