It was one of those gray afternoons when the Boston sky looked heavy enough to fall. Salt air drifted in from the harbor, and the maples along Commonwealth Avenue rattled like thin china. Claire Bennett stood at the top of the marble steps of the Harrington estate, broom in hand, when she saw him—small as a shadow, toes curling against the cold flagstones, arms crossed hard over a ribcage that had learned the shape of hunger.

A boy. Barefoot. Dirt on his cheekbone like a thumbprint. His eyes fixed on the front door as if the gleam of brass might be a door into warmth.

Claire glanced over her shoulder at the empty drive. The household was pared down for the afternoon—Arthur the butler out fetching wine for a dinner, Chef Rosa at the market, the driver taking a mechanic to check the Bentley’s brakes. Mr. Harrington was meant to be in Back Bay, a run of meetings that always crowded his posture and sharpened his voice. There was nobody to stop her from breaking a rule that had kept her employed and quiet for three steady years.

She descended the steps. “Are you lost, sweetheart?”

The boy shook his head, lips blue with cold. He looked at the iron gate and then back at her, as if any movement might scare the possibility of help away.

“Come with me,” Claire whispered. “Just for a moment.”

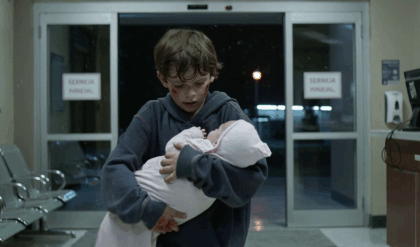

She keyed the side entrance and guided him through the service hall, past a row of starched aprons and the emergency exit map everyone ignored. The kitchen waited like a cathedral—copper pots shining in their ranks, sunlight falling in clean squares across the butcher-block island. Claire sat him at the small wooden table where staff took their breaks and set a steaming bowl of beef stew in front of him, the proper family porcelain be damned.

“Eat,” she said softly.

The boy’s hands trembled around the spoon. His first swallow was too fast; he gagged, then steadied, and the second spoonful went down like a promise. Claire stood at the stove with her palms pressed to the counter, watching him as if watching alone could keep him safe. One of the reasons she’d taken the job at the Harringtons’ wasn’t the money, not really, but the quiet—the sense that in a world that came apart easily, someone here had chosen to nail the floorboards down.

The front door slammed.

The sound ran through the house like a struck bell. Footsteps followed—polished soles on marble, the faint scrape of a briefcase—the music of authority. Claire’s breath stalled. A hundred small, safe decisions evaporated in the heat of one dangerous one.

William Harrington entered the kitchen expecting silence and efficiency. He found a boy in rags hunched over a porcelain bowl and a maid standing beside the stove with the guilty posture of a soul mid-prayer.

His briefcase slipped an inch. “What’s this?”

“Mr. Harrington, I—” Claire’s voice misfired and came out as air. “He was at the gate. He was freezing. I thought—”

William lifted a hand. The gesture cut the room cleanly into before and after. His eyes—blue like glare on an icy river—moved from Claire to the boy and stayed there. Something in his face went older by a decade in a blink.

“What’s your name, son?”

The spoon clicked against the bowl. The boy looked up. “Eli.”

Silence collected itself in the corners as if even the house wanted to hear the answer to questions not yet asked. William took off his coat and settled it around Eli’s shoulders with a care that made Claire’s throat ache.

“Finish your meal, Eli,” he said. “No one in my house goes hungry.”

It was not the reaction Claire had braced herself to survive. She felt weak with it—this mercy, sudden as summer rain. She waited for the scolding to come late and surgical, for a lecture about lines and the wages of crossing them, but it didn’t. Instead, William crossed to the sink, washed his hands as if to steady them, and leaned against the counter as Eli ate. Every so often, his gaze slid to Claire with an expression she’d never been inside before—gratitude threaded with grief.

By the time the bowl was empty, Claire had managed to reassemble herself enough to pour a glass of milk and set a warm roll within reach. William crouched to the boy’s level and spoke in a voice that had negotiated contracts and compromised senators: gentle and precise.

“Where did you sleep last night?”

Eli’s eyes dropped. “Behind a store. With a box.” He thought about it, then added, “It smelled like bread. Not the good kind.”

Claire’s fingers found the small silver cross she wore and pressed the cool metal into her palm until it stung. She’d grown up with a younger brother who was always hungry—Caleb, who’d figured out how to fall asleep fast to skip part of the ache—and the sight of this child at her kitchen table rearranged old scars.

William stood, decision making his posture. “We’ll make sure you’re safe tonight.” He glanced toward Claire. “We’ll start by warming him up. Hot bath. Real clothes. Then we call the right people.”

“Sir?” she asked, because there was risk in mercy and someone had to name it.

“If there are consequences,” he said dryly, “they’ll invoice me.”

In the guest bath, steam bloomed against the glass. Claire tested the water with her wrist the way her mother had taught her and set clean towels on the counter. Eli stared at the jets as if the tub might be tricked into becoming an ocean. “It’s just water,” Claire assured him. “It’s yours for as long as you like.”

When he was clean and swaddled in a robe the color of summer sky, William appeared with a shopping bag heavy with new clothes, a baseball cap with a block-letter B, socks that promised never to stop being warm. He had moved with the quiet efficiency of a storm warning—one call to his driver, one to the house manager, one to someone in the city whose number most people didn’t know. Power settled on him like a coat he’d worn long enough to forget its weight.

“Put on what you like,” William told Eli, and then to Claire, lower, “Call the Department of Children and Families. Ask for a social worker named Lisa McKenna. Tell her it’s William Harrington. She’ll come right away.”

“Do you… know her?” Claire asked.

“I know everyone,” he said. The way he said it sounded less like pride and more like confession.

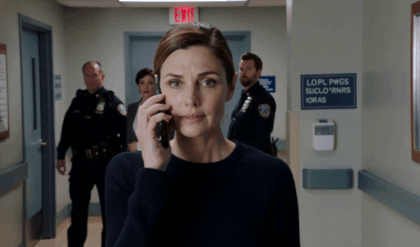

Lisa arrived in a navy parka that still smelled like the snowstorm forecast for Wednesday. She took in the picture with a glance: the boy with the fresh haircut and the socks too new to trust, the billionaire whose kitchen looked like a magazine and whose eyes looked like he hadn’t slept in a month, the maid with worry braided into her shoulders.

“Eli,” she said, crouching. “I’m Lisa. I’m here to make sure you’re okay.”

He nodded as if agreeing that okay was a place he could reach if an adult pointed long enough. When she asked his last name, he shrugged. When she asked where his parents were, he said, “I don’t have them.”

“No birth certificate, no medical records,” Lisa said to William in the study later, voice low. “He’s a little ghost. We’ll call hospitals and shelters; sometimes there’s a trail if you know where to look.”

William’s jaw tightened. “He’s not a ghost in my house.”

“Temporarily,” Lisa said. “If you’re willing, he can stay here as a kinship placement while we locate family or foster options.” She paused. “You understand there will be scrutiny. People will say you’re doing this for the press or to soothe a wound money can’t reach.”

William’s laugh was without humor. “People always say something.” He glanced at Claire. “Whatever they say, they won’t say it about her. If anyone so much as implies she acted improperly, I’ll correct the record myself.”

Claire blinked. Gratitude was a shy animal in her chest. It shifted and warmed and made her braver.

The house learned a new rhythm as if it had been waiting for one all along. Breakfast meant two bowls of cereal instead of one, and the clatter of a spoon that hadn’t learned to be quiet yet. Between meetings, William wandered into the library to read aloud—Dr. Seuss, a dog-eared copy of Goodnight Moon that had belonged to a daughter he’d never had, and then, when Eli’s questions expanded, a glossy book on constellations.

“Do you want to draw the stars tonight?” William asked once, as if the invitation meant more than paper and ink.

Eli’s yes sounded like relief. They lay on the carpet under a navy blanket and traced the sweep of Orion with a flashlight against the ceiling. The city hummed beyond the windows. Claire watched from the doorway, a dish towel in her hands she forgot to use. She had never seen William laugh before—not the polite sound he made at fund-raisers, but the unarmored kind that tipped his head back a fraction and put years on his face in the right direction.

Arthur returned from his errands and disapproved with the particular dignity of an old-school butler. “The optics,” he murmured, lips barely moving.

“The boy’s cold,” William said. “That’s the optic.”

Chef Rosa made grilled cheese with the kind of reverence usually reserved for wedding cakes. Eli ate until his eyes went round with the possibility of being full. The staff adjusted around him, a small planet with a new moon. When spring nudged winter off the stoop, Rosa taught Eli how to plant herbs in terracotta pots and told him basil tasted like summer.

At night, when Eli’s breath wheezed a little from allergies nobody had diagnosed because nobody had ever taken him to a doctor, William sat on the edge of the bed and learned lullabies off YouTube with the volume all the way down. Claire stood in the hall and translated the part of the language you can’t Google—the cadence, the patience, when to speak and when to guard the quiet like a candle.

“Why are you helping me?” Eli asked once, when the dark made truth easier to carry.

William searched for an answer that didn’t sound like a press release or a prayer. “Because someone should have helped me, once,” he said finally. “And didn’t.”

The newspapers found out anyway. They always did. A photo made the Globe: William crossing the mansion’s front walk with a small boy in a Red Sox cap, the child’s hand folded into the crook of his elbow. The headline taxed the supply of words that could insult and flatter simultaneously. Social media did what it did—praise like confetti, suspicion like rain.

Vivian Chen, Harrington Capital’s CFO, asked him dryly over a boardroom table, “Is this philanthropic impulse going to cost the firm money?”

William poured coffee with a hand that didn’t shake. “Probably.”

“Then let’s call it an investment,” Vivian said. “We’re overdue for a way to be human that isn’t a press kit.”

He created a new arm of his foundation within a week—Harrington House, a pilot program to connect kids who fall between systems with emergency shelter, doctors who don’t ask for insurance first, tutors who know how to hear a fear hiding in math. When the first check cleared, protests softened at the edges. They didn’t vanish; nothing real ever does, but the noise lowered enough for good work to be audible.

Claire learned to live in a house that kept surprising her. Once, William passed her in the hall and hesitated. “About that day,” he said, meaning the boy at the gate and the rule she’d broken. “Most people follow rules because they’re afraid. You broke one because you’re not.”

“I was terrified,” Claire said, honesty blurring her politeness.

He smiled. “Fear doesn’t get a veto.” He paused. “There will be a raise. And a title change. Housekeeper, if you want it. The staff already follows your lead.”

“I don’t do this for titles,” she said, because pride is a muscle that atrophies when you need it most.

“I know,” he said. “That’s why you deserve one.”

Some Sundays, William took Eli down to the Esplanade and showed him the river, wide and stern and honest—the way the light gathered over the Mass Ave Bridge in the late afternoon, the slow miracle of a swan boat’s wake. They found the bronze ducklings in the Public Garden and pronounced each one’s name, old-fashioned and perfect: Jack, Kack, Lack, Mack, Nack, Ouack, Pack, Quack. Eli’s laugh bounced off the water.

Lisa McKenna returned with updates that were most remarkable for their absence. “No records,” she said after a month. “No school enrollment. No medical visits. If there was a mother, she moved often and didn’t share. If there was a father, he left before leaving could be called that.”

“What does that mean for us?” William asked.

“It means, if you’re serious, we start the process.” She lifted a folder thick with procedures. “Temporary custody first. Then, if no relatives come forward, you petition to adopt.” She looked past William to where Eli was using a whisk like a magic wand. “It means you prepare him for walls that shift when we test them.”

“Prepare us, too,” Claire said quietly.

“You’re already ready,” Lisa said, and the certainty in her voice cut through a fog none of them had named. “That helps more than any form we’ll fill out.”

The first threat didn’t arrive as a man in a doorway. It arrived in a letter—scrawled, angry, a claim in bad grammar and worse intent. A man named Gus wrote that Eli was his. He wanted cash to go away. Security traced the envelope to a shelter in Southie, where half a dozen men knew the value of a headline. William sent DeShawn, his head of security, with calm instructions: protect the boy’s privacy; protect the shelter, too. DeShawn set a quiet watch on the house and taught Claire how to read the street through the windows.

“What if someone gets in?” Eli asked, small at the top of the stairs.

“Then we stand together,” Claire said. “And we don’t scare until we’re done being brave.”

A week later, someone did try. The attempt was sloppy and born more of desperation than strategy—a man at the garden gate with a borrowed tie and a forged social-work badge. He used Eli’s first name like a weapon and slid a hand toward the latch. DeShawn moved with the speed of a decision made a long time ago. The man left in a cruiser, his lie folding up like paper under rain.

After, in the calm that follows a small storm, William found Claire in the pantry staring at a row of neatly labeled flour bins as if order could be absorbed through the eyes. “I keep thinking about the first day,” she said. “How easy it would have been to keep sweeping.”

He leaned in the doorway. “And how much smaller the world would be if you had.”

They didn’t talk about being grateful for danger. They talked about the chores of safety—new cameras, a quiet meeting with a judge, an emergency plan that included passwords and rendezvous points. Claire wrote them on an index card and tucked it into the cookbook with the banana bread recipe Eli loved.

Spring took its time. Boston is like that—stingy with warmth until it isn’t, then shameless in its generosity. On Easter, the Harringtons’ gardener scattered eggs across the lawn even though Eli swore he was too old to care, then sprinted like he’d been born to chase color.

In April, a woman appeared at the front gate with a face like a map of places she’d never been allowed to rest. She asked for Eli in a voice that knew him. Her name was Tessa O’Rourke, and she had a frayed photo of a girl who might have been Eli’s mother if you squinted grief into focus. She explained in halting sentences that her sister, Maeve, had lived hard and loved fiercely and died in a shelter in Worcester. Maeve had a boy. A social worker once wrote a first name on a crumpled intake form, and Tessa had been walking toward that name ever since.

“Why didn’t you come sooner?” William asked, because questions like that come out colder than intended when fear is at the wheel.

“I didn’t know where to,” Tessa replied. “You ever tried to find a child who disappears every time the world blinks?” She lifted the photo. “I’m not here to take him away. I’m here to tell you his blood isn’t a rumor.”

Lisa verified what could be verified: Maeve existed; she died; there were no clean lines connecting then to now. Tessa had enough proof to braid a story, not enough to claim a life. They sat at the kitchen table—the same one where Eli’s spoon first clattered—and decided to risk kindness again.

“Eli,” William said, kneeling so he could look up into the boy’s face instead of down. “This is Tessa. She’s your aunt.”

The word hung in the kitchen, tender and dangerous. Eli’s eyes searched Tessa’s for the kind of recognition that children learn to stop asking for when it’s denied too many times. Tessa’s hands shook. “You look like your mama when she was too stubborn to be sad,” she said, and the truth in it made the room breathe easier.

They moved carefully. Tessa came twice a week, then three times, and learned how Eli took his tea (two sugars, nobody’s business). She brought stories of Maeve that weren’t only about her leaving: the way she danced to the radio even when the song was static; the bracelets she made out of red thread and hope. She brought a small box with Maeve’s handwriting on the lid—a recipe for soda bread, a Polaroid of a woman with a grin like she’d never learned the word almost, and a bus ticket stub that said ALBANY—BOSTON in black ink, the date half torn.

In May, the court set a date. The hearing would be at the Edward W. Brooke Courthouse, a building of glass and intention. Adoption, if the judge agreed, would make permanent what they’d already been practicing.

The night before, the house was quiet the way a chapel is quiet—the kind that asks you to be brave and promises to help. William ironed Eli’s small jacket with more reverence than he’d ever pressed into a contract. Claire baked a loaf of Maeve’s soda bread, her hands following the faded instructions like prayer. Tessa sat at the table with her chin in her palms and cried into a paper napkin the way women do when they’ve finally found a safe place to break.

“Will it change how you feel about me?” Eli asked William, eyes bright with a fear he didn’t have words for.

“Paper changes how the world treats us,” William said. “It won’t change anything I’d fight for.” He touched the boy’s shoulder, then, self-conscious about tenderness, cleared his throat. “It will make me your dad, officially. But you made me that already.”

The judge was a woman named Ruth Callahan who had hair like steel wool and a smile that didn’t bother with small talk. She read the file, asked the necessary questions, and studied the faces before her: the man who’d built more than buildings, the woman who had broken a rule and found herself in a family, the aunt holding her sister’s ghost by the hand.

“Do you understand,” she asked William, “that you are adopting not a headline, not an idea of yourself, but a boy who will push every button you have and some you don’t yet know exist?”

“I do,” he said, voice steady.

“Do you understand,” she asked Eli solemnly, “that this man will make you do homework and eat vegetables and go to bed when you’re sure the world is most interesting?”

“I do,” Eli said, the corner of his mouth tilting.

Judge Callahan signed with a flourish as if drawing a line between past and present. “Then by the authority vested in me by the Commonwealth of Massachusetts, I make official what has been obvious since the first page of this file: you are a family.”

Applause spilled into the courtroom because sometimes even the law wants to stand up and cheer. Tessa hugged Eli and whispered something that made him nod like a soldier receiving orders he wants to obey. Claire exhaled a breath she’d been saving for months and held the back of a chair because joy has a way of making the room tilt.

Outside, on the courthouse steps, cameras waited at a polite distance. William took Eli’s hand and prepared himself to be articulate. But when a reporter called his name, he shook his head and drew the boy closer. “Not today,” he said, and the firmness in it suggested there might be other days, but they’d be on the family’s terms.

Back at the house, balloons waited on the newel post, unwilling to be dignified. Chef Rosa had declared war on restraint and made a cake that could have fed the entire block. The staff gathered with the easy affection of people who had learned each other’s soft spots and chosen to guard them.

“Dad,” Eli said later, when the mess had settled and the house had resumed its evening heartbeat.

It was still a new word. It would be new for a long time. William had thought, before this, that the title would clink when spoken, metallic with effort. Instead, it fit like a shirt that had been waiting in the back of the closet for years.

“Yes, son?” he answered, and the word snapped into place.

“Thank you,” Eli whispered. “For everything.”

William smiled the kind of smile Claire had learned to recognize as rare and therefore precious. “No,” he said softly. “Thank you. You made this house a home.”

After the guests left, after the dishwasher hummed with the contentment of a job worth doing, Claire found herself alone in the kitchen with the quiet. She washed the porcelain bowl—the same one that had once held stew like a promise—and set it carefully on the rack. Her reflection in the window over the sink looked not younger or older but true.

She thought of all the moments that had known how to masquerade as small: a boy at a gate; a rule bent in the service of a larger one; a man who had learned that power is only useful when you set it down and lift someone with both hands. She thought of her brother, Caleb, who would have liked Eli and the way he’d learned to laugh with his whole body. She thought of her mother’s cross, cool against her skin, and of the way faith sometimes travels in the ordinary, wearing an apron and carrying a dish towel.

The front hall clock chimed ten. Upstairs, the low murmur of a bedtime story smoothed itself into silence. Outside, the city tangled with its own restless sleep—the MBTA sighing somewhere underground, a siren far enough away to be somebody else’s story. The house held them all, a roof and four walls and a promise—and a new name under that roof that had changed the air.

In the days that followed, normal reinvented itself. Eli’s sneaker scuffs on the stairs refused to be buffed out, and no one tried very hard. There were soccer practices where William learned sideline etiquette from parents who had never cared who he was at work. There were parent-teacher conferences where Claire sat beside him with a folder of Eli’s drawings and asked questions that made the teacher’s mouth lift at the corners. There were nights when the three of them ate takeout on the floor because the table felt too formal for the way happiness had decided to arrive—greasy cartons, chopsticks that gave up and became forks, laughter that knocked into the baseboards and came back around for seconds.

On a July evening that arrived hot and humming, they went to the Esplanade for the Fourth of July concert. The Boston Pops made the air itself sound like confetti. Eli fell asleep against William’s side just before the fireworks. When the first bloom of color opened over the river, William looked down at the boy’s face and thought of all the times in his life he had mistaken applause for love, headlines for home. He let the realization land and then pass. The real thing was heavier. It had weight and warmth and a heartbeat that, when pressed against his ribs, asked him to keep becoming the man who could be trusted with it.

“Do you ever think about the first day?” Claire asked him later, walking back across the Mass Ave Bridge, city lights stitched into the black water.

“All the time,” he said. “It’s how I measure what matters now.” He looked at her. “You risked everything.”

“So did you,” she said. “Just different kinds of everything.”

They fell into a comfortable quiet. The wind tugged at Claire’s hair, and the river went on being the river—patient, insistent, carrying the city’s reflections like secrets given willingly.

Weeks later, when school started and Eli came home with a permission slip crumpled in his backpack and a grin that suggested he’d learned to spell the hard words—persevere, responsibility, Harrington—Claire taped a new schedule to the fridge. Her own life had become a collage of small, necessary tasks: soccer shin guards in a basket by the back door; lunchboxes lined up like little soldiers; a standing Sunday night rule that pancakes are an acceptable dinner if you say grace twice.

One evening, Tessa came by with a stack of cheap, glossy prints. “Found some more,” she said, shuffling them like cards. “Maeve in Coney Island. Maeve pretending not to cry when she broke her ankle dancing and still kept going for two songs. Maeve on a bus to who even remembers.” She held one out to Eli. “You have her stubborn mouth.”

Eli studied the photo and touched the edge like he could smooth the years. “Does it make you sad?” he asked Tessa.

“It makes me hungry,” Tessa said, and when he looked puzzled, she laughed. “For more of this. For you. For the way being an aunt is like being given a second try at the kind of love that doesn’t have to end wrong.”

In October, the Harrington Foundation opened its first small shelter for kids who fall between systems. William gave a speech that wasn’t a speech so much as an acknowledgment, the way the tide acknowledges the shore without pretending it can keep from coming in. He thanked the city for being a place where second chances could be organized and funded. He thanked a list of people by name, saving Claire for last even though she’d told him not to. When he said her name into the microphone, she looked down at her shoes as if anyone could be expected to know what to do with that much attention.

After, a reporter asked Claire, “Do you think of yourself as a hero?”

She smiled, made of nerves and honesty. “No ma’am. I think of myself as someone who was lucky enough to be standing by the right door when it opened.”

The reporter pressed. “Would you do it again?”

Claire didn’t have to think. “Every single time.”

That night, the three of them sat on the kitchen floor with bowls of chili and cornbread and watched the local news pretend it had discovered kindness as breaking news. Eli leaned into William’s side and announced, “I think you should be President.”

“God forbid,” William said, and Claire laughed so hard she had to set her bowl down.

When winter returned—because in Boston it always does, a regular miracle with teeth—Claire pulled Eli’s coat from the hooks by the back door and checked the pockets for treasures: a marble that had somehow come home from the playground; a leaf shaped like a hand; a folded note from a classmate named Mia that said YOU ARE GOOD AT DODGEBALL in letters brave enough to be a headline.

Sometime after New Year’s, when the city had gone clean and quiet under snow and the world felt like it could be rewritten, Eli asked from the back seat, “Do people ever stop being yours?”

William met Claire’s eyes in the rearview mirror. “No,” he said carefully and completely. “Not if you don’t let them.”

Eli nodded as if filing that away under laws the world should obey. “Then I guess we’re stuck with each other,” he said, which is another way of saying saved.

On the kind of morning that begins like a sigh—coffee too hot, emails like mosquitoes—Claire opened the side door to take out the recycling and paused. A boy stood on the sidewalk, smaller than Eli by a year, in a sweatshirt that argued with the temperature. His eyes were open in the particular way of a child taking inventory of escape routes.

“Hi,” Claire said, because practices become principles if you’re patient. “You hungry?”

He nodded.

“Come on then,” she said, holding the door. “We’ve got stew.”

Behind her, in the heart of the house that had learned to be brave, a man and a boy looked up at the sound of footsteps and smiled in the way of people who remember their own first day by the same door. The kitchen smelled like garlic and good intentions. Outside, the sky was gray again, heavy with possibility. Inside, someone pulled another bowl from the shelf.

Later, when the house slept and the city went on breathing like a vast animal, Claire stood at the sink with water running warm over her fingers and thought about the math of kindness—how some sums don’t subtract when you share them. How a door can become a hinge, how a hinge can become a home.

If the world is a house with many rooms, someone still has to sweep the steps, notice the quiet shiver at the gate, and risk the order of things long enough to let grace in. She had done that once without knowing the name for it. She would do it again, and again, as long as there were bowls and spoons and hands to hold them steady.

In a city famous for its history, they were building a new one room by room—nothing grand, nothing that asked drums to accompany it, only the steady, ordinary song of a family: footsteps on the stairs, the low murmur of a bedtime story, the clink of a bowl set down for someone who needs it. It was enough. It was everything.