At midnight, my phone rang—my son’s nurse whispered, “Please… come alone.” I slipped through the hospital’s back door, where officers lined the hallway. One gestured for silence. When I finally looked at his bed, the sight nearly stopped my heart.

All the ordinary days that should have protected us—pancake mornings, weekend soccer scrimmages, the soft clatter of cleats in the dryer—collapsed into a single narrow corridor lit in the color of worry. People say disaster announces itself with crashes, with sirens. In my life, it came soft. A whisper. Blue uniforms like parentheses around a door. And a woman’s back in a lab coat, a hand tipping a syringe toward what every chart in this hospital knew would end my son’s life.

But that was the middle, not the beginning.

The beginning was an October morning outside Boston where the maples went loud as brass, where the light fell so clean you could almost hear it. I flipped pancakes while my nine-year-old son, Ethan, rehearsed his goal celebration at the kitchen table, elbows tucked, grin askew. His soccer jersey—blue with a stitched lightning bolt—lay folded on the chair back like a promise.

“Mom, is Dad coming to the game?” he asked, slipping into the practiced innocence of hope.

“Dad has a big meeting, sweetheart,” I said, plating a stack and buttering the top until the pat melted into a glossy lake. “He promised he’ll rush over if he can.”

Michael Bennett—my husband then—sold medical devices for a company that liked its conferences in cities with tall hotels and glass lobbies. He knew how to move in those places, chest forward, fist closed around a phone that answered to him the way we no longer did. He had been promoted that summer, a title with a sharper edge, a salary with commas, and a sheen of absence that seemed, at first, like ambition.

Ethan cut into the first pancake, steam curling up. “I’m going to score one for him anyway,” he decided, as if love were a math problem he could solve with effort.

That afternoon, my parents came to the field with their folding chairs and their thermos of hot chocolate. The air smelled like cut grass and someone’s dad’s aftershave. When Ethan caught a pass, stutter-stepped, and chipped the ball over the keeper, I stood so fast my chair rattled. He sprinted toward the sideline, two fingers raised in a V that meant victory or maybe it meant view me, Dad.

By the time Michael jogged up, tie loosened, the game’s clock had already blinked 00:00. “I made it,” he panted, tipping my forehead with a kiss, aiming another at Ethan’s hair. “How’d my champ do?”

“He scored,” I said. “You missed it by about thirty seconds.”

Michael winced, laughed, promised French fries. That night, with the television low and Ethan asleep, he made a grand announcement from the sofa: “Europe next summer. We’ll do it right—London, Paris, Rome. I want our son to stand under old sky and feel like everything is possible.”

The thing about declarations is that they draw a border around a life and say, Stay inside this. I didn’t know we were already wandering.

The dizziness came small at first. One day, Ethan slumped on the couch after school, paled, pressed the heel of his hand between his eyes. “I feel floaty,” he said, as if describing a balloon.

“Did you drink water?” I asked. “Eat your snack?”

He nodded. It passed.

Then another week, another episode. Again, and again. Soccer didn’t look like effort anymore; it looked like the world tilting under him. “I think we should get him checked,” I told Michael one Wednesday, standing at the sink while the last light went thin over the maple beyond our window.

“You’re right,” he said, to his credit, phone face-down. “Boston General’s got a good pediatric neurology unit. I’ll make a call.”

Boston General wasn’t a place I knew, not with the intimacy you earn in long nights and florescent mornings. The pediatric ward tried its best at softening: murals of whales and foxes, an aquarium with a fish that followed fingers along the glass. A therapy dog—a graying yellow Lab named Huck—made rounds twice a week with a volunteer in a red vest. Ethan met Huck in the playroom the first afternoon, a game of cautious petting turning quickly into fondness. “He understands me,” Ethan whispered into Huck’s ear, and the dog thumped the floor with his tail as if in agreement.

Dr. Johnson, the attending, had a sandy part in his hair and a way of listening that made you want to hand him your fear. He ordered an EEG, an MRI, and a full panel of labs. “We’ll keep him two nights,” he said. “It’s probably nothing serious, but let’s be sure.”

Ethan’s nurse was Mary—thirties, steady hands, a braid she wore looped like a question mark. “You ring, I run,” she told Ethan. “It’s our deal.” He laughed, reassured by arrangements that sounded like a game.

The tests went the way tests go: stickers on a scalp, the thunk of magnets, the pinch of blood. Ethan did what brave looks like at nine: he asked questions and then pretended not to care about the answers. Michael came the first night straight from a dinner with clients and kissed Ethan’s forehead with due ceremony. The second night he called at eight-fifteen, voice hushed, hotel-room quiet behind him.

“Emergency trip,” he said. “New York. I’m sorry.”

“The results are tomorrow,” I reminded him, anger cracking at its edges. “You promised.”

“I’ll try to get back by afternoon. Kate, I swear I will.”

I spent the evening playing Uno with Ethan and a boy from the room next door who wore a hoodie with dinosaurs and hooked his IV pole with the nonchalance of a cowboy roping a calf. At ten, I watched my son sleep—the way kids only do in cartoons, loose-limbed and honest. I went home to shower and collect his favorite hoodie, the one with the lightning bolt to match the jersey. When my phone rang at two-fifteen in the morning, every sound in the world went far away but that.

“Mrs. Bennett?” Mary’s voice was not its usual lake. It was a river after rain. “Please come to the hospital. Alone. Don’t call your husband.”

“Is Ethan—”

“He’s okay. Please hurry. Back entrance.”

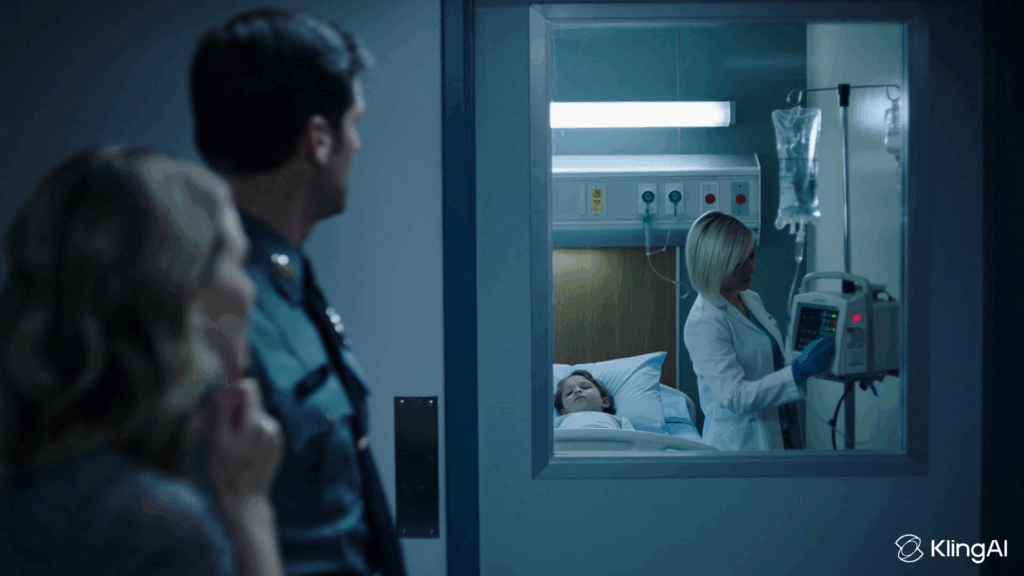

I broke the speed limit and my own rule about praying when you don’t mean it. Mary waited in the service hallway’s sodium light, eyes swollen, fingers clutching her badge as if it were a talisman. She pressed an elevator button with her knuckle and said, “Keep your voice at a whisper when the doors open.”

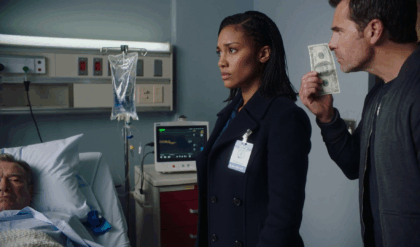

When they did, two uniformed officers and a plainclothes detective looked up from the pediatric corridor, from the strange stillness that occurs before a thing happens in earnest. The detective introduced himself without sound: a card, a nod, the kind of measured gaze that says he’s seen things get bad and knows the exact sequence of steps to prevent worse.

He led me to a window. “Look,” he mouthed.

Through the glass, Ethan slept, his mouth open a fraction, one hand in command of a corner of blanket. A woman in a white coat stood at the IV pole. She had the neatness of someone who gets what she wants because she has rehearsed wanting. Her dark hair was twisted into a low bun; a clip held the stray bits hostage. The hand holding the syringe moved with precision, a pianist’s confidence in a dangerous key.

When she turned, it took a second for recognition to outpace denial. Dr. Monica Chen. I had met her at Michael’s company holiday party three months prior. He’d said, “Old friend,” with his arm easy around my shoulders, with a smile that ran warm. She had laughed, eyes light, and I had thought: she is the kind of woman my husband is proud to know.

“Don’t move,” the detective whispered. He signaled. Doors flew open. The room that had been only ours became crowded with shouting—controlled, practiced—hands on forearms, a syringe clattering to linoleum, the liquid inside shattering into a galaxy of drops. Mary clutched my elbow. “She didn’t inject it,” she whispered fiercely. “I pulled the line and called the police the second I saw the order.”

Monica did not fight. She did not try to explain. When her eyes found mine as the officers cuffed her, something like a bottomless well looked back. Not hatred. Not surprise. Not even sorry. Just an absence where a person had been.

I wanted to lunge for my son. I wanted to take the entire hospital out of the equation and substitute my arms for every machine. But there were procedures. There was chain of custody. There was a detective with a voice low as gravel asking, “Mrs. Bennett, will you come with me?”

In the interview room, a clock ticked politely. Detective Aaron Wilson opened a folder and set its contents on the table as if they might bite. “I’m going to walk you through this once,” he said. “You can stop me when you need to.”

He began with the simplest knife. “We have reason to believe your husband, Michael Bennett, has been in a relationship with Dr. Chen for several years.” He didn’t say affair, as if a different word could make the blood look less like blood.

“No,” I said. It came out smaller than I intended. There is a split second where your life reaches for its old shape like a hand groping for the familiar switch in the dark. Then the lights come on and you see the furniture is already rearranged.

Photographs. Hotel lobbies I had never seen but recognized. A wine bar near South Station with a leather banquette. Two heads bent close. A hand in a back pocket. Dates in the corners, winter into spring into a summer I thought we had spent together at the Cape, while apparently there had been rooftops in cities where my name never crossed a reservation list.

Mary knocked and entered with a printout. “The order Monica placed was for piperacillin-tazobactam,” she said, voice steadying. “Ethan’s chart flags a severe penicillin allergy in six places.” She looked at me. “When he was six months old?”

“Anaphylaxis,” I said, remembering the tiny body that mottled red, the scream that didn’t sound like any sound I had learned to associate with him, the ER doctor who jabbed epinephrine into his thigh while I begged whatever ghosts occupy emergency rooms to take me instead.

“If that medication had run, your son would have gone into anaphylactic shock within minutes,” Detective Wilson said.

The rest of the night arranged itself without my permission: messages retrieved from Monica’s phone with a warrant obtained so fast you’d think it had been preprinted. Words from Michael to Monica that parsed my son like a problem to be solved. Details of his allergy typed out as if they were helpful trivia; then the pivot—Monica’s response about making it look like a rare but documented medical reaction, how they’d be grief-struck, how no one could blame anyone when medicine is imperfect. Michael’s reply: I trust you.

By the time a separate team knocked on Monica’s apartment door, Michael answered in a T-shirt and jeans, his voice calibrated to sleepy. He said he’d flown to New York. He had no boarding passes. He said his battery had died. His phone showed sixty-two percent. He said he’d been alone. A neighbor halfway down the hall described hearing laughter from Monica’s place an hour before.

When they walked him into the room where I was sitting, I felt something in me close like a door. He looked smaller in handcuffs, which is a trick of perspective, not redemption. “Kate,” he said, and my name snapped in half.

“You were going to kill our son,” I said. No one corrected my grammar to “arrange for his death.” Detective Wilson let the sentence stand. It had earned its lack of nuance.

“Kate, I—” Michael began, and then something in him gave way. He sat, slumped, and did not reach for me, which was the kindest thing he had managed in months.

At dawn I stood at the window of a different hospital room across town—we moved Ethan to a children’s hospital where Mary had connections and ethics—and watched the city wake. Traffic on Storrow came to as much of a halt as you can call rush hour merciful. In Ethan’s new room the walls were painted a mollifying ocean blue. Huck the therapy Lab made his rounds there too, an inter-hospital celebrity whose picture hung alongside Red Sox posters and paper cranes. Huck pressed his chin on Ethan’s bed and sigh-huffed like an old uncle settling into a story. Ethan, not fully understanding the edges of what had happened, combed his fingers through Huck’s ears and said, “He’s warm.”

“Warm is good,” I said, and meant it more broadly than I could say.

The dizziness, the new doctor said, was likely stress—nothing sinister in the imaging, labs unremarkable. Children’s bodies raise flags to warn us when the rest of our lives won’t. We were sent home with a referral for counseling, a recommendation for rest, and a schedule for follow-up. Mary stopped by off-shift with a bag of bakery muffins and a folded pamphlet about MSPCA at Nevins Farm. “They’ve got a reading-to-dogs program,” she said. “Kids practice out loud. Dogs don’t correct pronunciation.”

“What if we don’t have a dog?” Ethan asked.

“You can borrow one,” she said, and smiled, and something in me unclenched at the idea of borrowing softness.

The Commonwealth of Massachusetts moved quickly. The District Attorney’s office assigned an assistant DA who spoke with the clarity of someone who had learned early how to talk to people standing at the edge of their lives. Monica was charged with attempted murder, conspiracy, tampering with medical orders. Michael with conspiracy and solicitation. The hospital’s director, it turned out, had taken money to look the other way; he resigned so swiftly you’d think the shame had been prepackaged in a cardboard box along with his family photos.

“Do I have to testify?” I asked the ADA in a beige conference room with bad coffee and good intentions.

“Likely not,” she said. “Mary’s documentation is solid. The messages between the defendants are… persuasive. But I’ll need a victim impact statement at sentencing.”

I went home and opened a blank document and found I could not arrange anger and relief into sentences that behaved. Instead, I wrote about pancakes. About two fingers raised after a goal. About a therapy dog named Huck laying his face on my son’s thigh and asking nothing in return. When I finished, the page count surprised me. I deleted half. Left the rest like a note in a lunchbox: here is what you are taking from us, and what you cannot.

Michael’s lawyer tried something that courts used to call a defense. Monica’s lawyer did not try much at all. In a side hearing I wasn’t allowed into, Monica spoke about love as if it were an absolution. In the corridor outside, I ran into a woman in a cardigan whose hands worried each other like they were trying to get out of a difficult conversation. “I’m her mother,” she said, though she didn’t have to. “I’m sorry. I didn’t raise her to—” She couldn’t finish. I told her that I believed her on the first point and that apologies don’t build bridges across certain rivers. We stood together for two minutes that lasted a week. Then I excused myself.

At sentencing, the courtroom felt colder than weather. Michael wore a suit I had bought him on a sale rack in Copley years ago; that detail infuriated me more than anything else. When the judge asked if I wanted to speak, I said no and allowed the ADA to read my statement. It mentioned a boy who practices with a wall when no one is available to pass him the ball. It mentioned how quiet our house had become around eleven o’clock at night as if it were embarrassed to have believed in anything so loudly in the first place. It mentioned how love, improperly tended, can border on negligence.

The judge spoke in the past tense about people who were still alive. The numbers came down like weather we couldn’t influence. Fifteen years for Michael. Twelve for Monica. The director would not see the inside of a prison but paid enough money to fill a news cycle that wasn’t about us. Reporters texted; I didn’t answer. I took Ethan to the ocean instead, where the Atlantic threw itself at the shore until it tired and tried again, which is one way to survive.

We moved. Not far—the same school district, a different street—but far enough that Ethan’s bedroom didn’t hold the echoes of what I had mistaken for our life. I went back to work at the accounting firm and discovered that my brain liked balancing columns again, found comfort in work that returned answers that were right or wrong and never asked what to do with the space in between.

On Thursdays, Ethan and I drove to MSPCA at Nevins Farm. To the cats whose blinking consent made him feel trustworthy. To the dogs whose lives had been shuffled like cards and then re-dealt with a mercy we could participate in. He practiced reading The Phantom Tollbooth to a beagle named Comet who suffered a tragic case of only sitting for second graders wielding graham crackers. On the third week, a kennel attendant asked if we wanted to meet a mixed-breed with a caramel coat whose paperwork simply said: Maple. The dog leaned into Ethan the way weary people lean into truth when they finally hear it. “She picked us,” he said, and I said yes because sometimes you accept the verbs that children offer.

Maple came home and made us part of a pack. She learned the sound of Ethan’s laugh so well that she would trot into the room where it originated like she’d been summoned. She slept half on a bed she was too dignified to fully occupy and half on a braided rug my mother liked because it reminded her of kitchens from before. On bad nights, when memory took the shape of a hospital room door and my pulse went loud, Maple put her head across my shins, an animal’s benediction.

Letters came from the prison in Shirley, and I recognized the handwriting before I recognized any of the person it had once belonged to. I slid them into a drawer I labeled Withheld. When Ethan is older, I will present the drawer like a choice, because that is what it will be. For now, I keep the drawer closed and the cookies open.

Mary visited once a month and then every two weeks and then on Tuesdays without knocking because that is what family does when it has earned the right. She had been promoted to head nurse at a different hospital, proof that the world does not always punish the people we need most. On her second spring visit, she watched Ethan show Maple how to wait before chasing a tennis ball. “There’s a farm up in Carlisle that lets kids groom rescue horses,” she said. “You can smell the hay for a mile. You know, if you’re the smelling-hay kind.”

We were. Saturdays became acre-wide and horse-bright. Ethan learned that patience is a halter and kindness is a brush run firm along a flank. A pony named Daisy loved him with the passion reserved for small boys who move slowly. He talked to Daisy the way he talked to Huck, the way he used to talk to his father in the spaces where we still thought that word meant something other than genetic contribution. “You’re safe,” he told Daisy, which was functionally also what he was telling himself.

Late in May, at a U-10 championship at a field behind a middle school where the scoreboard sputtered its lights like an old man trying to remember a punchline, Ethan lined up for a penalty kick. The other team’s goalie was tall for ten and had an older brother’s swagger. Maple sat beside me, ears pitched, tail performing slow arithmetic in the grass. Ethan placed the ball, took four steps back, and nodded at it like a promise. He went left-right-left and then snapped his ankle and sent it high, upper ninety, a shot that taught the air a new shape. When the net shook, the parents roared in a way that is really just a sanctioned version of we are still here.

He ran to the sideline and did not look for a man in a suit. He looked for a dog and the woman who had learned how to be both mother and witness. Maple beat me to him, because that’s her way, and Ethan dropped to his knees and buried his face in her neck. “I did it,” he said into fur. Then he looked up at me and added, “We did it.”

At home, after a dinner of celebratory takeout, we sat on the back steps while twilight arranged itself into something a city can bear. Fireflies tried out their magic without commitment. Ethan leaned on my shoulder. “Mom?”

“Hmm?”

“What is family?”

I could have said blood. I could have said marriage. Instead I said, “People who love you on purpose.”

He nodded like he already knew but needed the sentence said aloud to make it permanent. “So Mary is family,” he said. “And Maple. And Daisy.”

“And Grandma and Grandpa. And your teammates. And Huck, even though he doesn’t live here.”

“And—well—maybe Dad is not family anymore.” He said it carefully, like walking on stones across a stream. I wanted to scoop him up and carry him. But I have learned that the only way children get to the other side is by placing their own feet down. “Maybe he’s just a person who helped make me.”

“That’s allowed,” I said, the air briefly thick with the weight of saying quiet truths out loud. “You get to decide what words you use for people.”

He looked at me, relief and sorrow sharing space behind his eyes like roommates who had learned to split the rent. “Okay,” he said. “I pick what keeps me safe.”

Summer came with its generous light and its lazy math of eighty-degree days multiplied by the number of afternoons you can fit into the backyard before the mosquitoes declare their own schedule. Ethan took a job watering the community garden down the block and brought home vegetables like trophies. We grilled corn and learned the trick with the wet paper towel that chars the outside without turning dinner into a rescue mission. On Thursdays, we still drove to Nevins Farm, even after Maple, because gratitude is best when practiced, not performed.

In August, the ADA called to say that Monica had written a letter to be delivered through official channels if we consented to receive it. “She’s not requesting contact,” the ADA clarified. “Just… acknowledgment. Your choice.”

I thought about it for a day and a half. I dreamed of glass syringes and woke with my mouth dry. Then I told the ADA to send it. The envelope arrived like a small bruise. Inside: a note on plain paper with none of the curlicue of apology. “I chose what I chose,” Monica wrote. “I told myself it was love, but I think it was the desire to be the only person in a room you shouldn’t be in. There is not a morning where I do not see your son’s face under hospital light. I cannot ask you for anything. I can only tell you that I am, finally, afraid of myself.”

I read it in the kitchen. Maple watched, head tilted, trying to calibrate the air for danger. I slid the letter into the same drawer as Michael’s, a new label: Seen. Not kept. Then I took Maple for a long walk along the Minuteman Bike Path, where kids rode their first no-training-wheels wobbles and retirees performed an interpretive dance with two small hand weights and a Bluetooth speaker playing the kind of jazz that forgives you without asking what you did.

In the second September after the arrest, Ethan’s school asked if I would speak at a parent night about resilience, a noun I distrust because it often disguises the way systems fail to be gentle. “Talk about the dog,” the counselor said, smiling at Maple like people do when they know a secret and the secret is that animals lower the temperature of rooms better than any thermostat. Ethan insisted on helping. We spoke together. He stood there, nine inches taller in two years, and told a room of adults that books read aloud to a dog count as brave. After, more than one father wiped his eyes in a motion they thought no one could see. A mother hugged me long enough that we both pretended it was normal.

We developed a fundraiser called Kicks for Paws: the soccer team scrimmaged the parents and all proceeds went to therapy animal programs at hospitals in greater Boston. Huck made a celebrity appearance wearing a bandanna that read HOSPITAL HERO in block letters. Mary handed out water and told Ethan to save me from heatstroke. He rolled his eyes and I pretended to be annoyed and together we replayed the choreography of an ordinary day that had once seemed impossible.

The first snow that winter came soft, a rumor that turned true with grace. Maple reveled like the universe had been remade for her paws. Ethan built a lopsided snowman and positioned Maple’s red collar around its neck like a medal. We came inside and drank cocoa the way marketing departments wish we would—mugs warming hands, laughter turning sharp air into a humid memory. The windows fogged and we wrote our names and then erased them with our knuckles, because who doesn’t love the drama of temporary art.

That night, after Ethan fell asleep with a book open across his chest, I sat at the dining table with the drawer open. A stack of letters that didn’t get to mean anything. A single letter that meant something I hadn’t yet decided. The house hummed as houses do when they are content. Maple settled at my feet, a sigh escaping her like permission. I thought of the corridor that had begun this chapter—the late hour, Mary’s whisper, the controlled rush of officers. I thought of the way a dog’s head can anchor a body drifting toward memory’s riptide.

People expect a speech at the end, a lesson, a carve-out of meaning that can be placed on a shelf and dusted. I don’t have one. I have instead a life that continues, a boy with a dog who wakes up early on Saturdays because the horses are waiting, a friend who became a sister because she answered a night call and believed her training more than her fear.

At midnight, two years after the phone rang, it rang again. I was awake, not from worry but because insomnia is a habit you don’t drop when the threat recedes. The caller ID showed the hospital’s main line and I felt the old hand at my throat, a gentle press. “Mrs. Bennett?” A man’s voice. “This is a courtesy call from the foundation office. We wanted you to know the therapy dog program you helped fund is expanding—two more dogs, more visits. We thought you’d like to hear it from us first.”

I looked down. Maple had lifted her head, sensing an invitation. I laughed then—this delighted, astonished sound that felt like it had been waiting for years behind my teeth. “Thanks for calling,” I said. “Midnight is our magic hour.”

After I hung up, I went to Ethan’s doorway and watched him sleep, taller now, the boy-ness still visible in the mess of hair and the one sock that had migrated to the far corner of the bed. I kissed my fingers and touched them to the doorframe like a ritual. Then I walked back through a house that held us the way a hand cups water—open enough to let the light in, steady enough to keep us from spilling.

In the morning, we would take Maple to the field. Ethan would practice corner kicks. Mary would text about cinnamon rolls at a new place on Mass Ave. Daisy would wait, patient as always, for the boy who reminded her that gentleness is not a weakness but a muscle. The world would tilt toward ordinary again, which is the bravest direction I know.

We are not who we were that first October morning when the pancakes steamed and the plan to see Europe sounded like a promise. We are a different constellation now. We are a mother, a son, a dog, and a woman who chose to be family and then proved it. If anyone asks what saved us, I’ll tell them the truth: a nurse who said come alone, a detective who moved like a metronome through chaos, a judge who assigned numbers that kept time from becoming dangerous, a community that showed up with casseroles and cleats and checks, and a Lab named Huck who taught a boy how to tell a story out loud to someone who would never interrupt. And Maple—Maple who taught us that love can walk into a house and change its temperature by degrees you only measure with your ribs.

This is what I know now: Disaster can arrive as a whisper, but so can mercy. And if one midnight can unmake your life, another can help you build a better one, the kind big enough for a beagle named Comet, a pony named Daisy, a hero Lab named Huck, and a caramel-colored dog who decided we were hers the minute we met. The rest is just weather. The rest is practice. The rest is us, moving toward the light like animals who remember the way home.