The air in Elm Ridge State Penitentiary had a way of flattening everything it touched. Fluorescents pressed a blue glaze over concrete and faces, over the catwalks and razor wire and the sheet-metal doors that swallowed men whole. Keys chimed from ring to ring. Radios clicked and hushed. Somewhere, unseen, a ventilation fan worked like a dry ocean, steady and indifferent. On execution mornings, even breath sounded rehearsed. The walls were good at keeping time.

Daniel Cole sat on the edge of the narrow cot and let his hands hang between his knees. He’d cut his own hair with a borrowed trimmer the night before, staring into a bolted mirror with a warped middle that made his face look like it was trying to escape itself. He had the calm of a man who’d been emptied out slowly over seven years. What was left no longer splashed when you shook it. He had learned to keep his voice low and his body still, to ride out tides until they forgot about him. A man could survive that way. A man could disappear that way too.

Footsteps paused outside his door. The rectangular slot slid open and a pair of eyes considered him. “Cole,” a voice said. The officer was Ramirez—broad-shouldered, a soft rasp that made everything sound like it had been lived through. “You ready for Warden?”

Daniel rose. “As I’ll ever be.”

The door’s hydraulics exhaled. Ramirez stepped aside, and Daniel stepped into the corridor as if it were a colder kind of room. He always looked down first, at the painted yellow line that guided your feet toward the places you didn’t want to go. The line had chips where boots had fretted. You could read a hundred small rebellions in it if you had time.

Warden Evelyn Hart’s office had a window someone had decided to keep clean. It framed a square of gray morning where crows slipped like signatures across the sky. Hart stood behind the desk, fingers steepled, the posture of a woman who had learned to ask for nothing and accept responsibility for everything. She had forty-nine years on her bones and most of them were organized.

“You have the right to make a final request,” Hart said, her voice level. “Within policy.”

Ramirez took a step back into his usual shadow, where he could watch and not interrupt. Another officer—Jenkins—leaned against the wall with a casualness that felt practiced, the kind some men wore like armor.

Daniel didn’t sit. He kept his palms open where everyone could see them. “I want to see my dog,” he said. “Max. Just once.”

Jenkins tilted his head, a quick flicker of mouth like he’d tasted something bitter. Hart didn’t move. “Your file says you owned a German Shepherd, confiscated at time of arrest.”

“He’s ten now, maybe,” Daniel said. “He was two when I found him tearing up a roll of insulation in a supplier’s yard. He slept under my workbench. He’d nudge my boots when I forgot to eat.” He found himself wanting to explain more than he had words for, and that was dangerous. “He’s not a pet. He’s…he’s the last thing that remembers me right.”

“You have no family requesting a visit,” Hart said. Not a question. Files had a way of making conclusions.

“No family that stayed,” Daniel said. “Max stayed.”

Ramirez looked at Hart, just once, a small muscle in his jaw clicking. Hart was a woman who believed in systems because human beings were worse. But she also believed in audacity when it served the truth. She’d seen men ask for guitars and clowns and a priest who never came. She had never seen a man ask to meet a dog in the yard, under the eyes of the towers, with a clock running like a stenographer.

“Ten minutes,” she said at last. “In the yard. Supervised. Any misstep, it ends. Understood?”

Daniel’s throat tightened without his permission. “Understood.”

Paper traveled. Phones clicked. The request, once granted, became a choreography. Somewhere beyond the concrete, a former animal-control officer answered a number she hadn’t seen used in years, and said she still knew the address where Max was living. Somewhere else, a man who’d taken the dog “temporarily” wiped his hands on his jeans and looked at a leash hanging by the door and thought about loyalty like it was a tool you had to oil. The world moved around the small idea of a reunion and pretended not to care.

They walked Daniel along the catwalk to the yard. Boots echoed. Jenkins led. Ramirez flanked. Daniel had learned to memorize. He knew which grate whistled in winter, which railing would rattle if you leaned on it wrong. He knew the yard always smelled faintly of pine cleaner and fear. Today there was something else too—a light dampness on the concrete, as if the morning had tried to wash itself but ran out of water.

The gate at the far end of the yard creaked open. Men on towers leaned forward like parentheses. Daniel could feel every muscle in his shoulders fail at pretending not to be eager. He didn’t blink for fear of missing the first second of Max that was not a memory.

He saw the ears first, the black triangles cupping the air. Then the tan blaze of a face he’d sketched in his mind a thousand times. Max trotted in with the steady confidence of a dog who had never once believed the world had greater authority than the man he loved. Two officers walked him on a leash that looked decorative against the reality of him. Max’s tail began a slow wag, then found the old rhythm like a song remembered at a stoplight. Four steps from Daniel, his body trembled; three steps, his head dipped and his eyes brightened; two steps, the leash slackened; one step, and the dog closed the space like a door.

Daniel dropped to his knees. The concrete was a rough reminder. Max hit his chest with a pressure that felt like the opposite of regret. There were sounds—whines braided with little low barks—as if the dog was both apologizing for and accusing the years. Daniel put his face into the ruff of Max’s neck and inhaled the map of a life: old leather from a collar he remembered, dust, a hint of the field behind the first apartment he could afford, the faint antiseptic of a groomer who meant well. Time was a different species when you were breathing it.

“Easy,” Ramirez said softly, to whom it wasn’t clear. The towers did their measured swivel. Hart, watching from a window above the yard, let one hand close into a fist against her thigh and then forced it open again.

Max quieted. Dogs know how to measure joy so it doesn’t spill on the floor. He pulled back enough to press his forehead to Daniel’s cheek and hold. Daniel lifted his hand to find the spot behind the ear where the coat trained itself into a cowlick. Max leaned into it with a groan. Seven years collapsed into the space between a hand and a skull.

A sound changed. Subtle, but dogs have a different dictionary. Max went still. His tail stilled mid-swing. His body slowly angled away from Daniel, toward the gate they’d entered through, toward a shape anyone else would have missed as just a man in a uniform standing correctly. The growl began down low, like anger learning to speak. Max’s lips did not lift. His body merely filled with a warning.

“Control your dog,” Jenkins said, stepping forward, the casual tone too quick to be casual. He kept his hands behind his back—regulation, yes, but the posture looked like a habit he needed.

Daniel put a hand along Max’s spine, felt the live wire hum. “Easy, boy,” he murmured, smoothing the fur backward. “It’s okay.” It was not okay. Max had growled at thunder, at a raccoon inside a trash can, at a small plastic Santa in a neighbor’s yard that played Jingle Bells on repeat. He had not growled like this—honed, weighted—at a human behind a threshold he could not cross.

Max’s eyes did not leave Jenkins. The dog’s ears tracked with tiny adjustments, mapping a man’s breathing. Jenkins’s jaw ticked once, and he looked away the way some men look away from mirrors. Ramirez watched everybody. He was good at watching life where paperwork would later insist it hadn’t happened.

After a minute that felt like a ten-digit code entered as slowly as possible, Jenkins turned and left the yard by the same gate, signaling to the tower for an open. Max’s growl bled into the air like heat, then collapsed, but he stayed standing, angled toward the absence. Dogs don’t forget doors.

“Your dog’s got a nose,” Ramirez said under his breath. “Any reason he’d know Jenkins?”

“No,” Daniel said, eyes still on Max. “He knows me. He knows wrong. That’s it.”

Hart called the yard from her office. The radio on Ramirez’s vest crackled. “Status?”

“All quiet,” Ramirez said. “Mostly.” He glanced at Daniel. “Dog gave Jenkins the business. Nothing else.”

Hart let the silence answer for her. She knew the inventory of quiet could sometimes be the loudest thing in a place like this.

They gave Daniel his ten minutes, then eleven when Hart didn’t speak into the radio again. Daniel whispered stories into Max’s collar bone about the time he’d burned a pan trying to make pancakes and Max had eaten the mistake off the floor with the solemnity of a priest. He apologized for the seven winters he hadn’t seen Max roll in snow. He promised nothing he had the right to promise and everything he needed to say out loud to someone who wouldn’t punish him for hope.

When they led Max out, the dog resisted only once, a small lean against the leash, as if to etch a dent in the morning. Then he went with the calm of a creature who trusted the next moment was not an enemy. Daniel watched until ears became less than geometry.

That should have been the end of a kindness offered and accepted. It should have been the beginning of the end of a day that had a signature and a time on it. Instead, it was a hinge.

Hart did not like hinges. Hinges meant parts moving that shouldn’t.

She called for Daniel to be brought to an interview room. “Bring the dog,” she added without looking at anyone. “If animal control is still inside.”

Ramirez raised his eyebrows. Jenkins’s mouth flexed again like a man chewing a memory he didn’t want. The interview room was a box with one arterial table in the middle and two chairs and a camera dome that blinked red when it wanted to be seen. Hart stood behind the glass for a moment and watched them assemble like pieces dragged back to a scene.

Max lay on the floor to Daniel’s right, body toward the door. Not sleeping. Dogs don’t sleep when the air has questions.

“Officer Jenkins,” Hart said, entering. “Your presence at the institution on the night of Cole’s arrest?”

Jenkins blinked like a man irritated by dust. “Off shift, briefly on grounds. I was dropping off paperwork.”

“Why is that not in any log?” Hart asked. Her voice didn’t change when she moved from interest to interrogation. It just stopped asking for permission.

“Because it wasn’t relevant,” Jenkins said. “I wasn’t on duty.”

Max’s growl returned, compact; you could have put it in your pocket and it still would have been heavy. Daniel put his palm on Max again, felt the muscles read the room in a language he understood better than any he’d heard in court. Hart looked from dog to man to Jenkins, and something in her face—not sympathy, not quite—shifted toward attention.

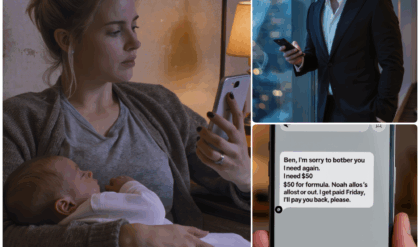

Ramirez spoke. “We’ve got a call, Warden. From a neighbor of Cole’s. Claims she saw a man in a dark uniform leaving Cole’s porch the night of the murder. Didn’t report it then because she was scared. Says she finally put the face to the uniform—saw Officer Jenkins at the grocery two days ago.”

The interview room arranged itself into a different shape.

Hart’s eyes flicked to the camera dome. “This is an internal inquiry, pending verification,” she said for the record. “Ramirez, pull every log we have from that night. Jenkins, you don’t leave the building.”

“This is ridiculous,” Jenkins said, but his voice had a new weight in it, like he was learning gravity all over again.

The order to prepare a stay of execution was a sentence Hart had heard in training but never said. She said it now without raising her voice. “Call the Attorney General’s office. Put the prosecutor’s number on the line. Bring Maya Whitaker in if she can be reached.”

“Whitaker?” Jenkins’s head jerked. “Public defender hound?”

“Independent counsel,” Hart said. “On retainer for last-minute reviews. Something every warden with sense ought to have.”

The building shifted its breathing. Words like “stay,” “hold,” “outside counsel,” “chain-of-custody audit” moved through halls that usually carried predictability. A man in a suit appeared in the doorway of a room where coffee had gone cold hours ago. A printer produced more paper in forty minutes than it usually saw in two days. Ramirez pulled a box from archives that had the dust of insults on it and brought it to a table where Hart would not sit until she knew what it refused to say.

Daniel was led back to his cell while the machine woke. They let Max spend twenty minutes in a small locker room with him, door closed, Ramirez standing guard with his back to them as if decency were a thing with a posture. Daniel put his forehead to Max’s again and exhaled. He did not ask for anything. He had already used up his request.

“You remember the night,” Daniel whispered. Max’s eyes were steady, dark coins. “You remember the knock. I know you do. I should’ve let you bark. I should’ve let you take the door off its hinges.”

He looked at his hands—the nails clipped short, the cut along the side of the left thumb from a week ago when a stapled legal packet had decided it was a weapon—and thought about the life those hands had built before they were disassembled by a verdict. He thought about his old garage, about the habit he’d had of labeling little plastic drawers with a label-maker he’d bought used, the plastic warming in his hand as if names could produce electricity. He thought about the night the police had come, about the confusion that had felt staged, about the bag of fentanyl found in a vent he’d never opened, about the neighbor found at the bottom of the back stairs with a head wound that had been translated into intent.

The first law of captivity is that if enough people say a thing about you, the thing becomes heavy enough to wear down your legs. The second law is that if you hold onto a single small truth—the way a dog smells when he’s damp, the sound he makes when he dreams—you can sometimes still stand.

Max lifted a paw and put it on Daniel’s knee. The paw had gray hairs around the toes that hadn’t been there seven years ago. Time had been busy when Daniel wasn’t looking.

“Time,” he murmured. “You thief.”

They took Max back out with a promise that felt accidental. “He’s not leaving the grounds yet,” Ramirez said. “Warden wants him close.”

Close was a word with elasticity. It could mean mercy. It could mean evidence.

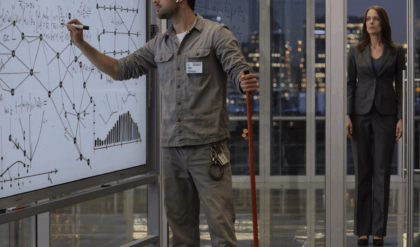

By midmorning, the warden’s conference room looked like a courtroom that had lost its sense of theater. Hart stood over a table covered in files, photos, and a chain of custody envelope that had a nick along the edge of the flap, barely a wrinkle but in the right light it looked like a lie. Maya Whitaker arrived in a navy suit that had been pressed by purpose, hair pulled back, eyes that moved fast without being careless.

“Tell me why I’m here,” Maya said, setting down a leather folio and flipping it open without looking.

“Because a dog growled,” Hart said. She didn’t apologize for the sentence.

Maya looked at the warden for a full beat. “I’ll take a dog over a jailhouse confession any day.” She snapped latex gloves on without ceremony and reached for the envelope. “Chain intact?”

“Allegedly,” Hart said.

Maya held it up to the light. “Who signed this in the second hand?”

Ramirez checked the log. “Primary evidence clerk was out sick. Substitute initialed. That’s…Jenkins.”

Maya’s eyebrows made a careful climb. “Of course it is.”

“Watch it,” Jenkins said from the door. He had been told to sit. He stood instead.

Maya turned to him with a smile that had the opposite of warmth in it. “Officer, if you’re going to threaten me, let’s do it on the record.”

Hart looked at Jenkins the way a metronome looks at a drummer who keeps rushing. “Sit down.”

He did. Eventually. The chair made a noise like a bad excuse.

They spread photographs: the neighbor’s back stairs, the broken railing, the party store bag with a receipt inside it time-stamped at 8:14 p.m., the receipt paid in cash with a serial number that could have been anyone’s. A photo of Daniel’s vent cover with its screws marred by a driver that was not his. A photo of Max caught mid-bark at the end of a leash that a friend had been holding that first night he was taken.

“Who took this?” Maya asked, tapping the Max photo.

“Animal control,” Ramirez said. “Officer Keane. Brought the dog in for holding pending disposition. Notes say dog ‘exhibited distress.’”

“Dogs don’t write adjectives,” Maya said. “Humans do. I want Keane.”

“Retired,” Ramirez said. “But she answers her phone.” He looked at Hart. Hart nodded.

Within the hour, Officer Keane sat in the chair Jenkins had been forced to vacate. She had a face that had been constructed by weather and certainty, and she looked at Max in the photo like you look at someone who once told you something true when the room was full of lies.

“He wasn’t in the house when I got there,” Keane said. “He was outside. On the porch. Whoever had him knew to leash him fast. Shepherds don’t like strangers going through their kitchen.”

“Who had him?” Maya asked.

“Uniform. Not my department.” Keane’s mouth thinned. “I didn’t see a badge number. I saw a face. I don’t forget faces.” She looked at Jenkins. “That one.”

The room rearranged again.

Jenkins laughed. It was too loud to be mistaken for confidence. “This is a witch hunt,” he said. “You people hear a dog growl and suddenly we’re overturning murders?”

“We’re not overturning anything,” Hart said. “We’re checking what we should’ve checked harder then.” She looked at Maya. “What do you need?”

“Stay of execution filed and granted,” Maya said. “Independent lab on every scrap of physical. Pull the original memory cards, not copies, from the exterior camera at Cole’s and from the cruiser dash cams. I want the maintenance logs for those cameras. I want the shift log from that night and the day after. And I want—”

She stopped. Max was in the doorway. Ramirez had allowed himself discretion and used it. The dog stepped in, paused, and then, with the kind of deliberate calm that makes a statement, walked to the conference table and put his chin on the edge near the chain-of-custody envelope as if to say the thing nobody in the room could: This smells wrong.

Maya looked at Hart without smiling. “I rest my case, preliminarily.”

Hart, who did not believe in omens, believed in noses. “Granted,” she said. “On everything.”

By early afternoon, the paperwork that had felt like a monolith began to admit it had seams. The stay came through faster than anyone would have predicted three years ago. The Attorney General’s office didn’t want a newspaper headline about a dog and a timer. The prosecutor had the tone of a man who wanted to appear cautious without admitting he had ever once rushed.

“Pending review,” he said to Hart over speakerphone. “We are in favor of ensuring accuracy.”

“I’m in favor of ensuring truth,” Hart said. “Accuracy is for rulers.”

Daniel listened to nothing for a long time and then to the radio outside his door. He had learned to place voices to faces through walls. He heard Hart’s careful brevity. He heard Jenkins’s clipped anger. He heard Ramirez say, “We’ll do this right.” He did not believe in words like destiny. He believed in men like Ramirez and women like Hart and in dogs like Max who could refuse to accept the wrong air.

In the late afternoon, Maya sat across from Daniel with a recorder on the table and a legal pad that would fill itself if she let it. Ramirez stood in the corner. Max lay by the door again, eyes open, breathing a tempo you could live by.

“Walk me through the night,” Maya said. “Your version. Not the file’s.”

Daniel did, and as he spoke the narrative fought him like a thing that had learned to live in someone else’s mouth. He talked about the neighbor—Tom—Ivers—who had once borrowed his drill and returned it with a bit missing. He talked about the sound that had woken him, a dull serration like wood protesting. He talked about the back stairs, the way the bottom step always caught the heel of a boot if you weren’t careful. He talked about opening the door and seeing Max furred like a storm, and the uniforms, and the cold that rushed the room like a second crowd. He talked about a bag in a vent that wasn’t his and a face that wasn’t supposed to be there in his kitchen, leaning like he owned the place.

“I didn’t do it,” Daniel said, the way a man might repeat a grocery list to prove he still remembered how. “But if I had, I wouldn’t have done it dumb.”

Maya nodded once. “I believe you.” She said it like a piece of evidence. “The question is why someone wanted you to look like you did.”

“I was working overtime at the shop,” Daniel said. “We were behind on orders. I did some side work. People brought me engines. Some of them weren’t particular about paperwork. Tom liked to talk about who was moving what. He liked cash. He liked cash that didn’t smell like anything.” Daniel looked down at his hands again. “I minded my business until someone decided it was theirs.”

Maya looked over at Ramirez. “Jenkins’s financials?”

“Clean,” Ramirez said. “But clean like a countertop: too clean.”

“Find the crumbs in the trash,” Maya said. “There’s always crumbs.”

The independent lab called at eleven that night. The corridor lights had cycled to their version of dusk. Hart answered even though she was supposed to have gone home at eight. “You have something?” she said.

“We have two things,” the lab director said. “One: latent partials inside the vent found in Cole’s kitchen that do not match Cole. They’re smudged, but the ridge detail on the ulnar side—could be promising if we can enhance. Two: fibers from the vent’s inside edge. They’re not from a common household cloth. They’re from nitrile gloves with a roughened grip. We pulled a narrow weft impression. We can compare to known samples.”

Hart closed her eyes. Opened them. “Known samples like from a box in a state-issued supply?”

“Like that,” the voice said. “If you have a purchase order. Different batches, different microtexture.”

Hart hung up and looked at Ramirez. “Jenkins’s duty locker.”

“Already on it,” Ramirez said. “With your warrant on my phone.”

Jenkins watched as two internal affairs officers opened the gray metal box that had been his companion for nine years. He watched as they pulled out a coffee mug, a replacement baton grip, a photograph of a woman who had decided to be his before she decided not to be, a box of nitrile gloves. The officers bagged the gloves like they were collecting a rare bird.

“This is harassment,” Jenkins said. “You let a dog snarl and suddenly my life’s an exhibit.”

“Your life is your life,” Hart said. “This is an exhibit.”

The cruiser dash cam footage, pulled from an archive that had mislabeled it “misc.”, offered another small mercy. There was a reflection in the window of a storefront across from Daniel’s house: the shape of a man moving, the glint of a badge chain swinging when it shouldn’t have been swinging because the man attached to it wasn’t on duty. You could deny a lot of things until you saw the way light moved around metal and knew it had a time and a place.

The story of Tom Ivers fractured. It was not just about a fall. There was an angle on the head wound that suggested he had already been compromised before he hit the bottom stair. There were bits of paint under his fingernails from a railing he had grabbed; that paint had a manufacturer’s batch that didn’t match Daniel’s latest can but matched a builder’s supply order billed to a third-party shell. The shell led to a name that led to a phone that led to a text message that said, “Night of. Make sure he’s not home long.”

Maya read the message and sat back like someone who had just confirmed gravity existed. “We don’t need to blow the whole precinct open,” she said to Hart. “We just need to blow one hole in one lie.”

Hart nodded. She didn’t need to be a hero. She needed to be right.

By dawn, the stay was public. Reporters gathered at the outer fence as if words would seep through. A woman with a red scarf and a microphone practiced her live look three times before the camera went on. Tessa Bloom, local court reporter, watched from the side and took notes in longhand because it made her remember details when her fingers moved. She wrote: dog; growl; warden with spine; Jenkins mouth; public defender in a navy that could cut.

Inside, Daniel lay awake and counted the beats in the HVAC again. He pictured Max asleep in the kennel room they’d borrowed for the night, the dog’s paws twitching while his brain chased something only he could smell. Daniel let himself imagine a door that opened and stayed open. Then he let the thought go because that was still the best way to keep breathing.

They brought Daniel to a different room in the morning, one with a table that had not yet learned anyone’s secrets. Maya spread out new pages. “The fibers match,” she said. “Gloves from a batch your department purchased four months before your arrest, two batches after Jenkins’s promotion to evidence transfer.”

Jenkins said nothing. Silence can be a tactic until it becomes a confession.

Ramirez slid a photograph across the table. “Photo of your truck, Jenkins. Night of the arrest. Parked two blocks up from Cole’s. Plate caught by a parking meter camera that doesn’t know how to lie.”

“You going to take down a man’s life over a parking ticket?” Jenkins said, but the fight had a hole in the middle.

“Over a dead neighbor,” Maya said. “And a bag in a vent.” She leaned forward. “Why him? Why Daniel?”

Jenkins stared at a point past everyone. “Because he was there,” he said finally. “Because he was simple. Because sometimes you need a story to end and he looked like an ending.”

It wasn’t a confession. It was a taxonomy.

“Who paid you?” Hart asked. “Don’t insult us by saying you did it for the hobby.”

Jenkins’s face did something small and complicated. “Nobody paid me,” he said. “I paid me. I like the feeling of edges lining up. I like closing drawers.”

“You planted a felony to feel tidy,” Maya said. “A man’s life for the sake of your desk.”

Jenkins looked at her with the eyes of someone who had been more comfortable in darkness than he’d expected to be. “People don’t miss what they never had.”

Daniel felt Max’s body surge to stand before he processed the words. The dog took a step, then another, and placed himself between Daniel and Jenkins, as if the English language had finally run out of uses and the time had come for a different grammar. Max didn’t bare his teeth. He simply stood, silent and inevitable.

Hart had heard enough. She stood. “Officer Brent Jenkins, you’re suspended pending arrest. Ramirez, call it in. Mr. Cole, you’ll remain in custody while charges are vacated. Ms. Whitaker, file your motions. I will personally escort this to the judge.”

It took three more days to do what a movie would have done in a montage. Judges sign in real ink. Clerks misplace the wrong folder at the wrong hour. A lab tech goes home sick and the backup tech needs to call a supervisor to approve the release of a file that turns out to be in a cabinet no one labeled correctly in 2018. But momentum is a real thing. It isn’t loud. It’s stubborn. It wore a suit and a badge and a leash and it kept walking one step at a time.

On the fourth morning, the gates opened for Daniel. He didn’t expect music. He expected the sound a gate makes when it discovers it can do the other thing. The world beyond the fence looked like a picture of a world: colors that weren’t institutional, edges that hadn’t been rounded for safety. The sky had stopped being a ceiling and returned to its original purpose.

Max was there, not because anyone had planned the poetry but because Ramirez had decided to make a phone call no one had asked him to make and Hart had decided to sign a permission slip no one had written. Max saw Daniel and made the sound dogs make when happiness is almost a problem. He pulled the leash out of a volunteer’s hand and ran like a definition.

Daniel dropped to one knee and buried his face again in fur he trusted more than oxygen. “We made it,” he said into the space where words become more than words. “We made it, boy.”

There were cameras. There were microphones. Someone asked him what he would do first. He said, “Walk,” because that was both an answer and an ambition. They walked. Past the van with the station logo. Past the fence with the sign that pretended it could explain anything. Into a parking lot where the lines were bright white and the heat coming off the asphalt made the air waver like indecision.

Maya caught up. “We’re not done,” she said, because truth has a schedule and it isn’t yours. “The charges are dismissed. But you need a life. You need papers. You need a job that won’t ask you about seven years you can’t give back.”

“I can wrench,” Daniel said. “I can build. I can make things remember what they were designed to do.” He looked at Max. “We’ll figure it out.”

Hart stood a little apart, as if too much human gratitude might be dangerous if it got on her uniform. Ramirez stood beside her. “You did the right thing,” Ramirez said.

“I did the thing I could live with,” Hart said. “That’s my threshold.”

Jenkins was arraigned two days later. The courthouse smelled like all courthouses: old paper and panic. Tessa Bloom wrote the headline she’d wanted to write for years: Stay of Execution Leads to Arrest of Officer in 2018 Murder Case. She thought about the dog, about how some stories didn’t need adjectives when you could watch a shepherd stand between a man and the world and make the world consider its behavior.

Daniel moved into a one-bedroom above a bakery that woke at three every morning. He learned the shapes of early again, the way first light moved across a wall like it was remembering choreography. He found work under the hood at a garage where the owner didn’t care about headlines and did care about his ability to listen to an engine until it told him what it wanted. He filled out forms that asked for addresses he didn’t have and he wrote “N/A” and refused to apologize to the box for its narrow imagination.

Sometimes at night he’d wake and not know where the door was. He’d sit up slow and wait. Max would come put his head on the mattress and breathe like an argument against panic. Daniel would put his hand on that skull and let the world decide to come back at its own pace. Sometimes decency is nothing more than someone willing to sit beside you until your brain stops lying.

In the spring, Maya invited him to a community forum on exonerations. He didn’t like the word. It sounded like a ceremonial thing, like they were pinning something to his shirt instead of taking something heavy out of his pockets. He went anyway because she had asked and because you don’t learn the new world by avoiding it. He said “thank you” too many times and meant all of them.

Hart didn’t attend. She’d done what needed doing, and one of the rules she lived by was that you didn’t collect receipts for morality. Ramirez went and stood in the back and left before the applause. It was how he was built. Tessa wrote another piece, quieter, about a shop above a bakery and a dog who had a bed in the corner by the toolbox and how, if you stood on the sidewalk at six a.m., you could see a man slide a door up and begin a day like it was the first one anyone had ever had.

Jenkins took a plea because control sometimes looks like surrender wearing a better suit. He admitted to evidence tampering and obstruction. The murder case against him depended on a witness who died and a text thread that was missing its other half. The law does what it can with what it has. It is better than nothing and worse than what a country deserves. He went to prison and learned how to count in a different key.

Daniel and Max drove to the river on Sundays. The old pickup he’d bought with a handshake and a price that had the kindness already factored in made a new noise at forty. He listened and decided it was a belt he could live with until he couldn’t. They parked where the grass gave up and let gravel do the job. Max chased smells in concentric circles. Sometimes they met a woman who threw a ball for her retriever with the seriousness of a professional. Sometimes they met nobody and that was perfect.

When people asked Daniel what saved him, he said, “A lot of folks doing their jobs when it would’ve been easier not to.” When they pressed, he said, “A dog who refused to be polite.” He didn’t say that some nights he stood in his kitchen and cried without sound because he had been given back something impossible and didn’t know where to put it. He didn’t say that sometimes he thought about Tom Ivers and the way a man could become a story other men used and how that was its own kind of violence.

In July, Daniel returned to the yard at Elm Ridge to speak to a group of recruits. Hart approved it because paradox is a thing you get used to if you like sleep. He stood in the same place where Max had planted himself and looked at the sky and then at the fresh faces who didn’t yet know which rules would matter when the air thickened.

“Listen to what doesn’t look like evidence,” he told them. “The thing that bothers you but you can’t name. The dog that growls at the wrong time. The envelope with the nick. The log with a coffee ring in the wrong place. You don’t have to be heroes. Just be allergic to neat lies.”

After, he found Hart near the door that had always sounded like that. “You didn’t have to let me talk,” he said.

“I didn’t,” she agreed. “But I did.” She looked at Max, who had aged another month and another inch of muzzle. “Take care of each other,” she said, and meant that more than any policy.

On a Tuesday that liked ordinary, Daniel came home to find a letter in his mailbox with a state seal and a check. It had more zeros than he had ever seen next to his name. He took Max for a walk before he opened it. He stopped at the bakery and bought two rolls, one for him, one for Max because the old dog had earned the indulgence and anyway who was keeping score. He sat at his kitchen table, the same place that once would have been evidence in a different life, and read a paragraph that called itself compensation.

He laughed. Not because money was a joke. Because it wasn’t. Because it was heavy in a way that didn’t press down. He put the check in a drawer. “We’ll fix the truck,” he told Max. “We’ll buy you a bed that looks like a small boat. We’ll get a plant and try to keep it alive.”

Max wagged like a metronome, remembering a song.

At night, sometimes, the air would do that penitentiary thing and flatten. Daniel would turn off the lights and stand at the window anyway. He would watch the building across the street with its blue TV glow and the couple who always argued about the good knives. He would let the world be unremarkable. He would remember that the last wish he’d asked for had had nothing to do with steak dinners or phone calls. It had been for eyes that didn’t judge, for a nose that refused to accept an arranged memory.

On the anniversary of the yard, he and Max went back to the river. The belt had finally given up and he’d replaced it. The truck sounded like itself again. The day was the kind that doesn’t try to be better than it is. He threw a stick badly and Max pretended to be impressed. They sat on the tailgate and watched a boy teach himself to skip rocks one rock at a time. The boy’s father cheered even when the rock sank without ceremony.

Daniel scratched behind Max’s ear, found the cowlick, and held until the dog sighed. “You saved me,” he said, a truth big enough to be ridiculous and somehow not. “You saved me, and I’ll spend the rest of the time making it worth the trouble.”

The trouble, as it turned out, was a good life. Not simple. Not neat. No drawer ever stays closed for long. But it was his. It contained engines that needed listening to and coffee that he could make without burning and a warden who would pick up the phone when a thing smelled wrong and a lawyer who would show up in navy and say “I believe you” like it was a crowbar, and a man named Ramirez who watched the rooms where conversations forgot to be recorded, and a dog who remembered in the only language that mattered.

Sometimes the truth doesn’t come from a witness stand. Sometimes it walks into a yard with a gray muzzle and a memory and refuses to be polite. And sometimes, when the world stops shaping you into its shape for a minute, you get to see the size of your own.

That night, Daniel left the window open. The city made the soft noises cities make when they’ve put their tools down. Max lay at the foot of the bed and dreamed a deep, twitching dream of something running but not away. Outside, a train called to nobody in particular. Inside, a man took a breath that did not belong to any institution, and let it out slow, and did not count it. He just lived it.

Days passed. Fall found the edges of leaves and did its slow work. The bakery downstairs switched to cinnamon and people wore their jackets even when they pretended they weren’t cold yet. Daniel tuned an old V6 for a woman who had saved her tips for the better part of a year; when the engine caught right, she looked at him like he’d returned something she’d left in a pocket seasons ago. He shook his head when she tried to tip extra and said, “Bring the car back if it starts lying to you.”

Word spread the way useful words do. He didn’t advertise; the world that needed him knew how to find him. Some came because they liked the smell of a shop with oil that had learned to behave. Some came because they’d read Tessa’s quiet piece and wanted to pay for something in cash and decency. A kid from the high school asked if he could sweep floors after class. Daniel said yes and then said, “Also, you’ll learn how to hear.” The kid had a good ear. The kid also had a skateboard and tried to teach Max how to ride it. Max looked at the board the way he looked at all impracticalities and wagged once as if to be polite.

Every so often, Hart would send a postcard. She never signed her full name. Just “E.” and a line like, Keep your tools sharp. He’d put the postcards on the refrigerator with magnets shaped like states. He had Ohio and he had Kentucky and one day he’d have the rest if the bakery lady kept bringing them back from her sister’s road trips where she collected magnets like evidence that she hadn’t stayed put.

Maya took him to lunch once in a place with glass walls and salads with names. She talked to him about a fund she was starting for men and women who came out of wrong rooms into the right light. He didn’t like being on a brochure but he liked the idea that somebody else might not have to ask a dog to fix what a system had broken. “You can keep my name off it,” he said. “But you can keep my time on it.” She nodded, not writing anything down, which was how you knew she meant it.

The case on Jenkins receded the way even loud storms do. He became a number in a system built for numbers. He worked in a laundry where other men wore initials on their chests that did not belong to them. Sometimes he thought about the sound of a growl in a yard and the way it had cut a line across his life like chalk. He told himself he would’ve been caught anyway. He told himself lots of stories at lights-out and believed enough of them to fall asleep.

On a winter morning, Max hesitated at the stairs. His hips had started to keep track of the years. Daniel had built a ramp for him out of plywood and grip tape because love is woodworking when it’s not everything else. Max pretended the ramp was beneath his dignity and then used it like a gentleman. They adapted together because there wasn’t another plan.

At the vet, the doctor had the kind of voice you use when you’re telling a friend a hard thing you wish wasn’t true. “He’s old,” she said. “He’s earned all of this. We can make the rest easy.”

Daniel nodded because nodding was cheaper than trying to talk. He bought the expensive joint chews and the good food and the bed that did look like a small boat. Max climbed into it like a captain humoring a new ship.

They had another year. It was a year of shorter walks and longer sits. Of slow mornings with coffee and the sound of a dog’s nails on hardwood marking where he’d been. Of the river less often and the stoop more. Of the kid with the skateboard coming by after school to let Max supervise homework.

On a day the bakery chose to make all the blueberry muffins at once, Max woke Daniel before the alarm by putting a paw on his arm and holding it there until Daniel’s eyes opened. The dog’s breath was sweet and wrong. The body had decided something and the mind was catching up. Daniel lay on the floor with him, cheek to cheek, and breathed like a man memorizing. He told Max about the first day he’d brought him home and the hole Max had made in the insulation under the sink and how he’d pretended to be mad because pretending to be mad is easier than admitting you’re happy. He told Max about the yard and the gate and the growl and the way the world sometimes does the math right if you insist long enough.

When it was time, he took Max to the vet in the truck with the belt that now sounded better than most things. He sat on the floor again because floors are honest. The vet was kind and efficient and left enough silence for a man to say goodbye without an audience. Max put his head in Daniel’s lap and sighed the sigh of a creature that knows a job well done and doesn’t need a certificate. Daniel held him while the world shifted into a different shape one more time.

After, the house was too quiet and the bed too big and the ramp a monument he didn’t know where to put. He built a wooden box in the shop with corners that matched and sanded it until it felt like something you could trust your hands to hold. He put Max’s collar in it and the first tennis ball and a photograph a neighbor had taken of the yard that day, Hart a small figure at the window, Ramirez a shadow, Daniel on his knees and a dog like a fact.

He took the box to the river and sat on the tailgate again and told the water the same story he’d told the vet’s floor. Then he went home and fed himself and slept and got up and went to the shop because the best way to honor a thing that saved your life is to live it in a way that would make the thing wag its tail.

Months later, he met a woman at the store where the aisle of screws goes on forever. She was reading labels with a seriousness he recognized. She had a dog hair on her sleeve and didn’t apologize for it. They talked about thread count and then about coffee and then about music and then about the fact that they were both people who had learned the hard way that the good knives in other people’s kitchens don’t cut for you. She came by the shop. She met the kid with the skateboard. She stood by the ramp and said, “Leave it.” He left it.

He didn’t replace Max. That’s not how it works. But one spring a shepherd mix showed up at the garage door, ribs countable, and decided to audit the oil changes. The dog had one ear that flopped wrong and a bark that sounded like a laugh. Daniel tried to find the owner. He put up signs. He asked around. No one claimed him. The dog chose. Daniel nodded. “All right,” he said. “You can help.” He named him River because that’s what brought everything in his life to the same place.

River learned the ramp, out of respect. He learned the shop’s smells. He learned to put his head in Daniel’s hand when the day got tight. He learned the spot behind the ear where the cowlick was trying to form. Daniel learned you could love again and not be treasonous.

There were still nights when the air went penitentiary-flat and he had to move through the rooms to remind them who they belonged to. There were mornings when the news would say a name like a verdict and Maya would call, her voice clipped in the way hers got when she needed help. He’d go sit in a courtroom again and fold his hands and look like a man it was safe to tell the truth around. He’d go to the yard at Elm Ridge once a year and stand at the line where the concrete ends because rituals are a way to tell time that doesn’t make you late.

People asked him for a story. He told them the only one that mattered: A man asked for a dog and got a life. A dog smelled a lie and the lie fell down. A warden said yes to a sentence she had never said and it turned out to be the right one. An officer watched a room and then another room and carried the quiet between them like a useful thing. A lawyer wore navy and used words to open locks. A reporter wrote without adjectives. And the world, which is ordinarily terrible at apologies, offered the slightest version of one.

He’d shake his head at the end like he couldn’t quite believe his luck. He’d scratch River’s ear and the dog would wag like a metronome, like a memory rephrasing itself into something livable. And then he’d go back to work, because engines lie when you ignore them and people do too, and he had learned to listen until the truth made a sound he recognized.

When he finally sold the truck, to a kid who had saved all summer and looked like someone who would take care, he included the ramp in the price because love is transferable in pieces. He bought a used van and built shelves for tools and left one space empty because there should always be room for the thing you don’t know you’ll need.

On a morning like the first one but not, years later, Daniel stood in a yard again. The chain link was different and the tower had a bird nesting on its edge and the sky had a warmer blue stitched into it. He closed his eyes and heard keys and radios and the whole building pretending it didn’t want to know how the day would end. He opened his eyes and looked at the gate. He waited for nothing in particular. Then he turned and walked back to the van where River waited in the passenger seat, one ear doing its best to stand up straight.

“Let’s go work,” he said. “There’s a belt that’s lying to a woman and we said we’d fix it.”

River wagged. The van started. The day agreed. And Daniel drove into a version of America that was as imperfect as the first one and better in the only way that mattered: he was free in it, and he knew what it took to keep another person free when the air got heavy and the walls tried to keep time with the wrong song.

Once, years after the headlines had learned to be quiet around his name, he got a postcard from a town he’d never been to. No return address. Just a picture of a river and the words, handwritten: Sometimes the truth comes on four legs. He put it on the fridge with the others and didn’t try to guess who sent it. He didn’t need to. He fed River. He turned the sign on the shop door to OPEN. He put his hands on a job that needed them. And he kept listening for the small sounds that meant the difference between a lie and a man who got to go home.