They had polished the mahogany to a mirror and set lilies on either side like sentries, white petals reflecting the nave lights of St. Bartholomew’s on Park Avenue. The organist played something somber and clean, the kind of music that sounded like winter sunlight through old glass. The press had been kept on the steps, drones grounded, cameras turned back by men in dark suits with coiled earpieces, because Richard Hamilton had paid for privacy the way wealthy men paid for everything—quietly, completely.

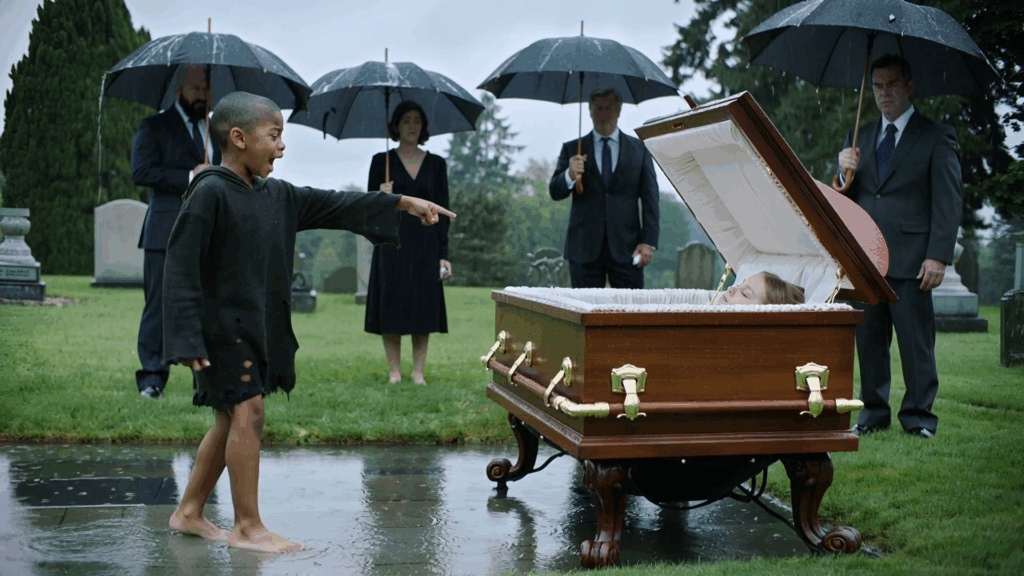

He stood three feet from his daughter’s coffin, hands folded against ribs he couldn’t quite get air into, and studied the carved arc of the lid as if it could tell him what to do next. Twenty-three. That number had no edges to grip, nothing to bargain with. The last message she’d sent him, two days earlier, was a photo of coffee in a paper cup with Columbia’s crown pressed into the cardboard sleeve. His answer had been a thumbs-up. He would grow old and die with that small blue thumb in his mind.

The pastor began. Words like comfort, eternal, rest tilted and fell. Richard barely heard them. He watched his wife, Catherine, seated in the front pew, knuckles white around a damp handkerchief, gaze fixed on the aisle as if Emily might still walk down it and sit beside her, cheeks wind-flushed from the storm, apologizing for being late to her own funeral.

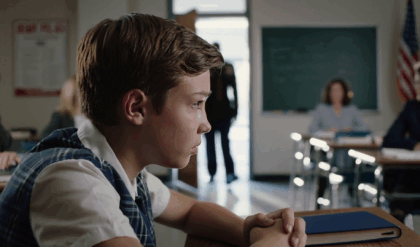

Footsteps broke the liturgy. Quick, uneven, a cadence that carried its own weather. A boy pushed through the gate at the back of the nave, slipping a hand through before the usher could close it. He was thin and taut with motion, hoodie dark with old rain, shoes splayed at the toes like tired birds. The suits moved. The boy saw them and didn’t stop.

“Your daughter is still alive!” he shouted. His voice struck the vaulted stone and rang. “She’s alive!”

Silence is a creature that can rear up when it’s startled. It threw the entire church backward. Catherine’s hand covered her mouth. The pastor’s Bible lowered by an inch. Richard turned.

He had made a billion dollars on decisions that looked reckless from the cheap seats. He was not a man who shared control. Yet some primitive jury inside him stood and said, Wait. The child’s eyes were not wild the way he’d seen wild eyes. They were fixed, urgent, and horribly sincere.

“Let him speak,” Richard said, his own voice unused, rusted.

The suits looked at one another, then eased back a step, but only a step. The boy stopped at the aisle, hands open, breathing quick.

“My name is Marcus,” he said, chest heaving. “Marcus Reed. I live … out there.” He jerked his chin toward the street as if pointing at the entire city. “I know what happened. Emily Hamilton isn’t dead. They forced her off the road. I tried—” His throat closed with a sound like a swallowed sob. “I tried to stop them. She was breathing when they took her. Please, sir, don’t put her in the ground.”

If a man is drowning and someone throws him a rope, he does not ask for its provenance. Richard didn’t realize he had moved until his hand was on the coffin. He looked at the pastor. The pastor looked at a physician seated two pews back, a friend of the family who had offered to attend. The doctor, a compact man with gray at his temples and steady hands that had spent three decades practicing stillness inside living bodies, rose.

“Open it,” Richard said.

Someone gasped. Someone else whispered, Don’t. The lid whispered on its brass hinges. Emily lay as the funeral home had prepared her, lashes a soft line against pale skin, mouth closed like a hesitant thought. Richard had held her on the day she was born and had never imagined he would see her not moving ever again. He had braced for the sour finality of death. What he saw instead cut him through with a merciless, impossible hope.

The doctor leaned in, fingers steady at her throat, then at the delicate hollow where collarbone met neck. Seconds turned physical in the air. The doctor’s eyes lifted and found Richard’s.

“There’s a pulse,” he said softly, almost to himself. “Faint, but present.”

The church made a sound, a single living organism drawing breath. Catherine folded at the waist with a noise that broke his heart all over again, a keening that had been waiting for permission to be joy.

“Call EMS—now,” Richard said. The suits were already moving, radios at their sleeves chattering like insects. The pastor crossed himself, lips moving in quick prayer. Richard slid his hand under the pillow, lifting Emily’s head, and felt heat against his palm that he had thought he would never feel again. He looked at Marcus.

“How do you know this?”

Marcus didn’t flinch. “Because I saw the other car. Black SUV, no plates on the front. Pushed her off the FDR near the Seventy-Third exit—there’s construction there, the barrels were set out. I was sheltering under the overpass. They pulled her out while the hood was still smoking, and one of them said, Make sure. The other one had a syringe. I yelled. They ran. I dragged her to the open, waved down a guy with a phone, and we called. Then at the hospital they said she was gone.” His voice thinned. “But I saw her chest move, sir. I know what I saw.”

Richard’s life had been a walled city with high gates and a guard at every post. It had protected him and imprisoned him. Now a boy who had nothing had reached over the wall and pulled his heart out with two hands. Richard looked at his daughter—alive—and then at the boy—alive in a way money couldn’t buy.

“Stay with me,” he said to Marcus. “Whatever this is, you’re part of it.”

The sirens smudged the block with their color. EMS took Emily within nine minutes of the first call, an eternity and the beat of an eye. In the ambulance, the paramedic with steady shoulders and a Queens accent said, “Pulse is weak—BP low—pupils reactive,” words that made a scaffolding where Richard placed his faith. Catherine rode with their daughter. Richard stood on the steps and watched the ambulance disappear into midtown traffic. When he turned, Marcus was where he had said he would be: still at the bottom of the church steps, hands jammed into pockets, head down like he was bracing for a blow he’d learned always arrives.

“Come with me,” Richard said.

“People don’t like me near their cars,” Marcus said without bitterness, only as a recitation of a fact.

“Then we’ll test the limits of what people like.”

Richard’s driver, a former Army MP named Gabe Rourke who had been with the family for eight years, opened the rear door of the black S-Class. Marcus hesitated. The leather looked too clean even to touch. Then he climbed in and sat on the edge of the seat as if ready to leap out the second he was told to. He did not ask for food or water. He asked, “Which hospital?”

“Presbyterian.”

Marcus nodded as if he had been keeping a map in his head for years.

On the drive up Park and across to Madison, Richard tried on the word gratitude and found it too small. He had spent a career building a portfolio of leverage. It had never once occurred to him that the most valuable thing a stranger could hand him would be the truth.

At NewYork–Presbyterian they took Emily directly to a private suite in the neuro-ICU where glass walls made families feel included in their own helplessness. A team assembled with the brisk choreography of those who practiced hope for a living. They spoke in a language Catherine and Richard pretended they understood. Toxicology. Bradycardia. Paralytic agent. They used the phrase “coma-like state” and “non-fatal dosages.” They said there would be scans and quiet, both of which were hard work for the living.

When the nurses had positioned Emily and taped down new lines with care that had the weight of prayer, when Catherine’s sobs had become shivers and she had drifted to a chair in the corner with a warmed blanket and a cup of tea she would not drink, when the glass door had been pulled nearly closed, Richard looked at the boy sitting cross-legged in the corner of the waiting area like a pilgrim who had finally made it to a holy place and wasn’t sure what to do now that he had arrived.

“Why did you help her?” Richard asked.

Marcus studied his own hands, palms mapped with scars that were not old. “Because there was a time somebody could have helped my sister and didn’t.” He said the next part as if he were laying something down that was heavy and he had carried a long way. “Her name was Maya. She was nineteen. She got sick. We lived with our aunt then, and when our aunt’s boyfriend decided we were too much trouble, we lived wherever there was a roof. One night Maya passed out behind the Port Authority. People walked by.” His mouth twitched. “People always walk by. I shook her. She woke up. She said she was okay because that’s what you say when you can’t afford to be anything else. A week later she wasn’t.”

A memory crossed Marcus’s face like cloud shadow. “I’m not leaving somebody if I can help it. That’s all.”

Richard thought of the insulation he had mistaken for virtue. He had not walked by, because he had arranged his life so the places you walk by were not on his route. “Your sister,” he said carefully. “She died?”

Marcus nodded without looking at him.

“What happened to you after?”

“Same thing that happened before. I got good at hiding.”

Richard had spent years mastering the art of eye contact that could end negotiations. Now he learned a softer discipline: he looked and did not look away. “You did a very brave thing today,” he said.

Marcus shrugged, uneasy, a boy unused to receiving any sentence that had the word brave in it that wasn’t followed by a laugh.

Richard’s head of security arrived inside the hour, salt-and-iron serious, clipboard tucked under one arm like an oath. Gabe stood at his shoulder, their shorthand as fluid as a language. They had worked collectively through bomb threats and blackmail, the leak of a merger that had made and unmade fortunes in a day. A daughter in a hospital was a different battlefield.

“Find who touched the chain of custody,” Richard said. “Ambulance, ER intake, anyone who signed a chart or whispered an order. If an intern’s roommate says she saw something on Insta, I want to see it.”

“You think what the kid said about orders is real?” Gabe asked, not looking at Marcus but not not looking either.

“I think my daughter is alive because he told me the truth. That makes him the most credible witness in the room.”

By dusk, a nurse in triage had admitted to being told to list “no resuscitative efforts indicated” by a supervisor whose supervisor answered to a medical director with unusual friends in finance. She had not asked questions because questions slow your life down in ways that a person with two jobs cannot afford. She cried when she finished talking and kept repeating I’m sorry, which was both true and insufficient. Names surfaced. Numbers were checked against numbers. Backgrounds that had looked boring in the morning had holes in the afternoon.

Richard made three calls. One to the district attorney whose campaigns had once benefitted from Hamilton checks. One to an acquaintance at the Bureau who owed him a favor that was not actually a favor but a shared understanding of leverage. One to Naomi Bennett.

Naomi had retired from the FBI at forty-seven because she had gotten tired of pretending the ocean of paperwork translated to safety. She had a quiet office in a third-floor walk-up on West 20th and a reputation for being where you looked when you wanted the truth with edges. She arrived in a black field jacket with a notebook and the kind of calm that reads as power.

“This is Marcus,” Richard said. “He saw what happened.”

Naomi asked Marcus to walk her through it. He did, carefully, twice, the way you talk when you know your words might be used later against men who make worlds bend. She asked him, “What did the syringe look like?” and “Did you see a tattoo on anyone?” and “Which side of the SUV hit her rear quarter?” as if she had been on the road with him under the overpass.

“Injection in the field would explain the bradycardia without trauma,” she told the toxicologist. “Look for alpha-2 agonists, anything that suppresses without anesthetic gestalt. And paralytics that clear fast.”

Marcus watched these people move around him as if he had wandered into a movie where the characters knew their lines. When Naomi finished with him, she surprised him by saying, “You did good.”

He didn’t know what to do with that sentence. He put it in the pocket of his hoodie like a lucky coin.

Catherine woke at midnight with a start and a raw throat. Richard was still by the bed, his body curved like a question toward their daughter. In thirty years of marriage, she had never seen him smaller than his suits until now.

“She used to fall asleep in the car,” Catherine murmured, staring at Emily’s hand with the pulse oximeter like a tiny red star. “My mother said I let her nap too long. She said I was spoiling her. I told her my job was to spoil her with safety and then let the world take what it wanted.” Tears slipped and disappeared into the warmed blanket. “I didn’t think the world would be so greedy.”

Richard took her hand and didn’t let go.

Emily dreamed of rain on the windshield and a voice that said, Make sure. In the dream she had been angry at something and wasn’t sure what. The anger turned into a cold so deep she thought of ice fishermen in another country. She heard someone call her name and thought it was her father when she was eight and they raced in Central Park to the playground at Heckscher. She turned toward the voice and saw a boy with a hoodie like a flag of a country that had not yet been created.

Morning came as it always does in hospitals, with lights raised and tasks recited. Marcus fell asleep in a chair and woke with a nurse putting a cup of orange juice on the table beside him. “You staying?” she asked without judgment.

“As long as I’m allowed.”

“You hungry?”

He said no because no had better consequences than yes. She put a muffin wrapped in cellophane on the table anyway and said, “That’s for whoever sits in that chair.”

By noon, Naomi had security camera footage from the Department of Transportation showing a black Tahoe without front plates riding Emily’s rear quarter panel like a shepherd guiding a sheep toward a break in the fence. A mile earlier, the Tahoe had been parked on the shoulder with its hazards on. Two men had stood at the guardrail watching traffic the way fishermen watch a river. When Emily’s sedan passed, they moved.

“Plate on the back is a fake,” Naomi said. “Letters correspond to a series stolen last summer from a dealership in Jersey. The SUV is likely a rental paid in cash or with a fraudulent identity. But this isn’t amateur. This is planned. The syringe in the field, the order to list her as non-viable—someone with both reach and resources.”

“Who hates me enough to do this?” Richard asked softly.

Naomi did not say the truth: power is not a pie; it is gravity, and everyone believes they deserve more of it until they can’t breathe. Instead she said, “Let’s build a list. Competitors. Enemies. Friends you trust too much.”

Richard gave her names. Victor Armitage at VantagePoint Global, a man who turned corporate raiding into a gentleman’s sport. Serena Cole at Talus Capital, who smiled with all her teeth. Two board members with long knives for votes. A CFO named Marlowe Trent, whose spreadsheets were perfect and whose eyes never seemed to be.

Naomi wrote each name down and added three of her own. People whose names did not cross the front page but should have. A doctor called Silas Bloom who consulted at three hospitals and had been sued by a family upstate for a wrongful DNR that had vanished from the docket. A fixer sometimes known as Calder, sometimes as nothing, who moved men from one side of bad decisions to the other.

“What was Emily working on?” Naomi asked, turning to Catherine. “Was she involved in any … projects?”

“She volunteered at a drop-in center on the Lower East Side,” Catherine said. “On Saturdays. She didn’t tell her father because she thought he’d send guards and ruin the trust.”

Richard closed his eyes. He wanted to argue. He couldn’t find a place to stand.

“She cared,” Catherine said simply. “It made her feel like she had hands that could touch the world and not just point at it.”

“Did she mention anyone there? A boy, a woman—names?” Naomi asked.

Catherine shook her head. “She kept the stories and left the names.”

Marcus shifted. “I saw her there,” he said, voice careful, like he was stepping on stones across a river. “Twice, maybe three times. Didn’t know her name, just that she looked like someone who knew where the exits were. She served chili and didn’t flinch if you asked for seconds.” His mouth lifted at one corner. “She talked to people like they weren’t problems.”

Richard looked at him. “You knew her.”

“Not like that,” Marcus said, and for the first time there was heat in his voice, a flare that defended her dignity and his. “I knew her like you know a person who doesn’t step back.”

Naomi wrote one more note. “If Emily was volunteering at the drop-in center, she may have seen something that doesn’t love light. The timing of the crash could be coincidence. But I don’t like coincidence. I like cause.”

At twilight, the hospital dimmed its lights to pretend at evening. The city outside glowed at the edges. Naomi stepped into the hall to take a call. When she stepped back in, her face was a shade tighter.

“Two men tried to get access through the freight entrance twenty minutes ago with badges that looked real enough to trick a night tech,” she said. “They were denied because the night tech has an ex who works at Bellevue and knows a sloppy badge when he sees one. They ran.”

Richard’s chest burned. “They’re still trying.”

Naomi nodded. “We move to a more secure floor. Now.”

The transfer happened like a trick: lights, wheels, a route mapped by two security officers in front and two behind, Naomi moving like a metronome at the head of the bed. Marcus stayed right where he had been asked to stay until he saw a janitor’s cart parked in an odd place at the turn near the north elevator. He had learned to read rooms the way other people read books. He didn’t touch the cart. He didn’t need to. He changed his position by two steps so his body was between the cart and the IV pole.

The man who stepped from behind the cart would have been a question mark to anyone else. To Marcus, he was an answer: wrong shoes for a janitor, too heavy, ankles bulging the way they do when a holster sits on top of a sock. Marcus moved without ceremony, slipping the brake on the cart with one foot while shoving it forward with both hands. The cart, weighted with cleaning supplies and a spare box of floor wax, hit the man’s shin at the exact moment Naomi’s voice cracked in the air—“Down!”—and Gabe came up from behind with a tackle he hadn’t used since Fort Bragg.

The man went down hard. Security dogpiled. Somewhere a nurse screamed in a way that meant she had screamed before. The second man stepped from the stairwell with a look that said he’d expected the first to do the job. Naomi put him on the ground with a joint lock precise enough to be art.

Afterwards, when the doors were sealed and the police were called and someone from the hospital apologized so many times the word became a bead of sweat, Naomi leaned on the wall for a counted breath and looked at Marcus.

“Good eyes,” she said.

He shrugged as if to shake it off. His heart felt like a classroom of kids had rushed into it shouting. He made his face still and put the feeling with the muffin in the pocket with the coin.

One of the men carried a phone that had self-destruct protocols. It didn’t self-destruct fast enough. Naomi got a number and a series of messages that were designed to mean nothing if you looked sideways. If you looked straight on, they meant see her under, see him under, see this through. A payment had been wired from a shell that traced back to an investment fund in the Caymans that handled money for men who never smiled in photographs because no one recognized them anyway.

The DA’s office moved. Search warrants gathered like weather fronts over offices where doors had always opened. A medical director resigned via email and took a flight to Mexico that didn’t land because the pilot discovered a fuel imbalance and turned back for Newark, where a marshal was waiting at the gate. Someone photographed the man looking less like a doctor and more like a person who had always wanted to be seen and then wanted very much not to be.

In the small hours of the next morning, Emily opened her eyes.

It was not cinematic. There was no sudden sound cue. It was slow—blink, breath, blink—and then the eyes that Richard knew better than his own tilted toward the ceiling, toward the light that was always too bright.

“Hey, kid,” he said, and the word kid was a prayer.

She tried to speak and couldn’t. The nurse touched her arm, and Emily looked at her and then at Catherine and then finally at Richard, and the smallest smile any of them had ever seen changed the room.

Marcus stood in the hall with his shoulders against the cool glass, letting the world narrow to what he could handle. He did not go in because he had rules for himself about the distance you keep between hope and your body. Naomi stood beside him and didn’t say anything. It was the most useful thing she had done all day.

By afternoon, Emily could whisper. She remembered the rain. She remembered the SUV in the mirror, black and too close. She remembered a horn and barrels and a feeling like the car had pivoted on an invisible hinge. She remembered hands. One of the hands had a scar near the thumb, a crescent as if someone had taken a piece of him when he was small and given it back wrong. She remembered the word make, then the word sure, then the river of silence.

Naomi wrote down “scar—right hand near thumb” and “barrels—Seventy-Third” and “make sure.” She did not write down the way Catherine looked at herself in the reflection of the glass and did not recognize the woman there.

The next day, Richard called a board meeting. He used to love board meetings the way a chess player loves the moment before the first move. Now he felt like a man having a conversation in a burning room.

“I will not discuss personal matters,” he said when someone asked if there was anything they could do. “We will discuss our exposure to shell entities that intersect with our philanthropic arm. We will discuss any contract awarded in the last six months that was not explicitly vetted by two independent compliance consultants. We will discuss names.”

Marlowe Trent adjusted his cufflink and smiled with practiced sorrow. “Of course, Richard. We’ll do everything we can.”

Naomi watched the meeting from a room down the hall through a glass panel that had been designed to make shareholders feel included. She watched Marlowe’s eyes not move the way guilty eyes do when they are being good. She wrote his name larger and then crossed it out and then wrote it again.

On the third day, Marcus walked with Naomi to the drop-in center on the Lower East Side because the guards wouldn’t let him go alone and because Naomi thought the city speaks differently to people who have lived outside in all weathers.

The director, a woman named Alma with forearms strong from lifting boxes and a voice like gravel that has learned to sing, took one look at Marcus and said, “You’re the kid who helped the Hamilton girl.”

“News travels sideways,” Naomi said.

Alma nodded. “Everything in this neighborhood does.” She led them through a back room where donated coats hung like a forest of ghosts. “She did good here,” Alma said. “Kept her head down, didn’t take pictures, didn’t use the place like a confessional. Asked questions, the right kind. Last week she was asking about a guy who’d been treated rough by some men with nice shoes. He’d told her somebody was running a hustle through the clinic next door. Prescription pads. Kickbacks. Insurance fraud. Boring crime that pays.”

“Names?” Naomi asked.

“Guy’s street name was Ducky. He’s around when it rains because the subway warms the tunnels then. Men with nice shoes?”