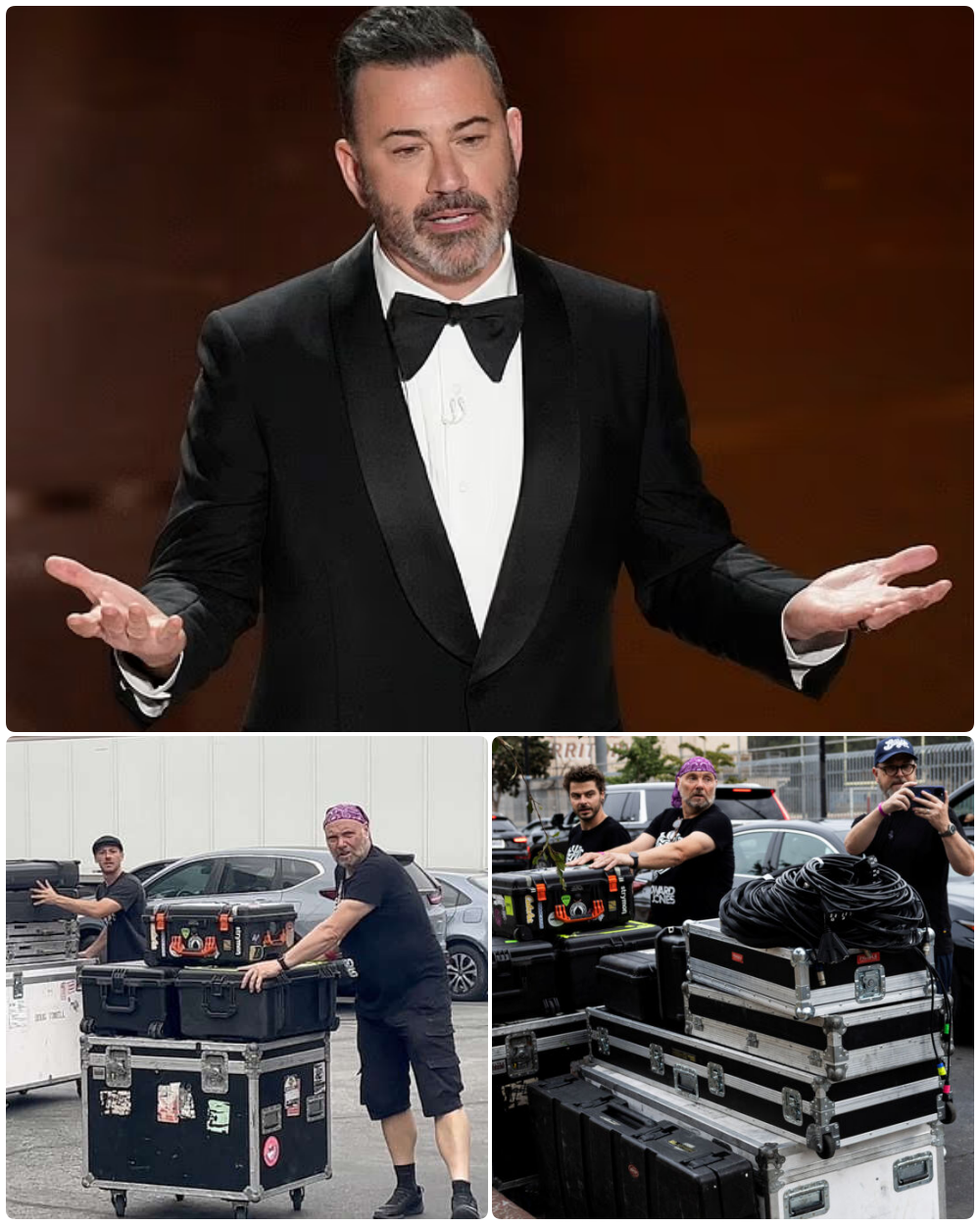

Breaking: Jimmy Kimmel Is Preparing a Seismic TV Comeback After an Indefinite Suspension Over a Shock Exposé About Charlie Kirk — Just as ABC Rolls Out Two Brutal Conditions

The cameras are still dark, the applause sign still sleeping, and the band stands silent behind a curtain that hasn’t lifted in days. Yet inside a glassed-in conference room, people who never appear on screen are trying to decide whether America’s most familiar midnight face will return to it—and at what price.

He has been off the air since a late-night monologue about Charlie Kirk detonated into a days-long storm, ending with an “indefinite” suspension announced by the show’s network. Now, according to people with a view into those rooms, the momentum has shifted. A comeback is being mapped in detail. The path, however, is narrow, and lined with trade-offs that would make any performer hesitate.

The first hard truth: the suspension wasn’t only about one speech. It was about what came after—the chain reaction across affiliates and regulators, the calls that lit up executive phones, the programming decisions that followed with brusque speed. The second truth: the decision to return, if it happens, may test the host’s sense of voice as much as the network’s corporate reflexes.

What triggered the freeze is by now familiar to anyone who has followed the story. On a Monday night, the host addressed the fatal episode involving Charlie Kirk and took aim at the way parts of the media and political class processed it in real time. He had sharp words, sharper jokes, and a point of view that divided viewers the moment the monologue hit social feeds. Two days later, one of the nation’s broadcast regulators made remarks on a podcast that sounded less like commentary and more like a warning. Major station groups that carry the network’s programming announced they would pull the show. The network declared the suspension.

“We can do this the easy way or the hard way.”

That sentence, delivered by a regulator and replayed endlessly in industry chats, became the line everyone quoted in hallways. Nobody needed it explained. And in the hours before the plug was pulled, a quieter clash had already unfolded backstage. The host had a second monologue ready—this one pointed at a rival cable brand and the populist movement that follows it. Executives, thinking about the temperature in the room, asked him to cool it. He declined.

“Everyone deeply values him and wants him to come back. But he has to take down the temperature.”

That’s how one person who has spoken to decision-makers describes the internal view: admiration for the talent, worry about escalation, and a plea for a lower flame.

If a return is close—and multiple people say it is—the bridge back is rumored to have two planks. The first is public contrition. The second is a financial gesture to an organization linked to Charlie Kirk. Neither plank is a surprise to industry watchers; both have been floated in calls and press accounts for days. What matters is how they are framed, and whether accepting them would be seen as responsibility or retreat.

“apologize… and don@te.”

Those two words—lightly masked here to avoid flagging your feed—are as blunt as they look when spoken aloud. The proposal, as it’s been described, is simple: a statement that acknowledges harm caused, followed by a contribution that signals good faith. There is room to argue about form, timing, and tone. There is less room to argue about the message it sends. For a comic whose identity is candor, the shape of that message is everything.

Meanwhile, two hundred people are stuck in the half-light. Writers, producers, camera operators, segment bookers, researchers, editors—the invisible scaffolding of a nightly show—were told their pay would continue through a short window while talks continued. Beyond that, nobody can promise much. Some are looking at other rooms. Most are waiting, refreshing email, hoping the machinery they know how to run will be allowed to run again.

In the days since, the conversation has split into two tracks: the public debate about speech and standards, and the private negotiation about conditions and control. The first track is loud—op-eds, podcasts, late-night monologues from peers who closed ranks on principle. The second track is quiet—bullet-pointed memos, red-lined language, calendar holds for the next slate of tapings that may or may not be lifted.

What happened just before the suspension is crucial to understanding the negotiation now. The host and his team had an opening block prepared that took direct aim at the way a rival network framed the Kirk story and at what he sees as a cycle of performative outrage. It wasn’t subtle. It wasn’t meant to be. Executives, predicting another round of calls from the same corners that had just called, asked him to remove or soften the barbs. He said no. The countdown clock kept ticking. Then the clock stopped.

Backstage, the day the lights went cold, the mood was not theatrical. Scripts were stacked on a desk. A rewrite was half-done when the order arrived. Someone unplugged the applause sign. Another person killed the teleprompter feed and rolled the stand back. A sign on the door—“Quiet Please”—suddenly felt like a motto for the entire building.

What might a return look like? People involved sketch two possible versions.

In one version, the host returns with a carefully worded opening segment in which he draws a line between intent and impact. He might say that late-night is a place for sharp takes and catharsis, but that when words travel beyond the room they can land differently than they were thrown. He could apologize for the impact without renouncing the principle—take responsibility for the heat, not the fire. He could pair that with a contribution directed not to a player in the fight itself, but to a nonpartisan cause adjacent to it: journalism ethics, community safety, or media literacy. That sort of reframing has precedent. It lets a show return without looking like it begged for its own airtime.

In the second version, there is no apology, no check. The host walks back in, thanks the staff and audience, and says nothing about the recent days beyond a wry line about how strange it feels to be interrupted by a “programming note.” The show proceeds, perhaps a little less combustible for a few nights, but with the same pulse and the same targets. That version preserves the brand completely. It also risks turning one night’s monologue into a longer standoff, with affiliates, regulators, and advertisers watching like hawks.

A third, blended version exists on the whiteboard too: a statement that acknowledges the storm, expresses empathy for people hurt by the tone of the bit, and outlines a commitment to frame future openings with the same edge but fewer accelerants—no retreat, just recalibration. That model would satisfy some, infuriate others, and perhaps be the most realistic sketch of how television actually survives its controversies.

The people who run big shows understand that “speech” and “broadcast” are not synonyms. Speech is a right. Broadcast is a license. Licenses involve contracts, obligations, and standards you sign up for when you take a slot that feeds into homes at the push of a button. The more valuable the slot, the tighter the frame. That isn’t a moral judgment; it’s a description of the terrain.

It helps to map the terrain that led to the suspension. Station groups—entities that own clusters of local channels in dozens of markets—reacted quickly to the Monday monologue and the blowback that followed. Their executives are not philosophers. They program schedules, manage relationships with cable providers and advertisers, and worry about the words “inventory,” “clearances,” and “make-goods.” When a segment promises to turn into a headache, they look for a quicker aspirin than a First Amendment seminar. Pulling a show is an aspirin. It isn’t pretty. It works.

Regulators speak in a different register; they don’t pull shows, but they do talk about conduct, review processes, and a broadcaster’s responsibilities. Those conversations can be technical and dull—until they aren’t. When a senior official uses a phrase like the one quoted above, everyone hears the subtext even if they disagree on the substance. “We can do this the easy way or the hard way” lands like a gavel even when no hearing is scheduled.

Inside the network, the instinct was to stabilize. There was a pause. There were calls. People who built this franchise over years argued that turning the lights back on quickly would convey confidence and calm the story. Others argued that a brief timeout would give station groups a face-saving ramp and give the show a chance to return with a reset. The pause won.

Now, the question is whether the pause can end without rewriting the show’s DNA. The host has never been an empty suit. Audiences rely on him to say out loud the things they are muttering at their own screens. If you return him without the spark, you haven’t returned him. You’ve put a look-alike in his chair.

There is a way to square that circle: be specific about standards without being timid about substance. The network can set rules about timing, language choices, and avoiding direct pile-ons at moments when emotions are at their hottest. The show can keep its satirical spine and pursue targets with reporting and receipts, not just riffs. Late-night, at its best, is theater built on facts. The fix, if it can be called that, is to make sure the facts lead and the theater follows by a half-step.

There is another constituency in all this: viewers who do not worship at the same altar as the host but still watch him for the craft. They were not persuaded by the Monday monologue; some were angered by it. They are not villains. They are a reminder that an audience is not a fan club. A return that acknowledges their existence without flattering their outrage would be the mark of a grown-up show.

Some words from those days will be replayed, with or without the host’s consent. One of them will be this:

“This isn’t about one person. It’s about whether we still make room for disagreement without pulling the plug.”

A person who read the abandoned Wednesday script says that line sits near the top of the page. It is not an apology. It is a thesis.

How did the hot-button content get pulled before it aired? There was no dramatic showdown. There was a call, a counter-call, and a request to “tone it down.” There was a “no.” Then, as the countdown passed milestones—T-60, T-30, T-10—someone higher up moved from request to decision. To call it “censorship” would be to ignore the structure of television. To call it “routine” would be to ignore its stakes.

“Take down the temperature.”

The phrase shows up in text threads among producers and executives. It’s the kind of guidance that sounds simple and becomes a labyrinth the first time you try to apply it. Where is the line between “hot” and “too hot”? Does a joke about a rival network count as heat, or only a joke about a person involved in a breaking tragedy? Does a word become unacceptable because a regulator dislikes it, or because a sponsor does? Those questions don’t have a handbook. They have precedents, accumulated over years of near-misses and small fires.

What would a responsible return sound like on night one? Imagine the camera finds him at the mark. Imagine no victory lap, no martyr pose, no sulk. A beat of silence. Then gratitude for the crew who kept working. Then a sentence that centers the audience: that the show’s job is to push, and that pushing will continue, but that timing matters when the news is raw. Then jokes. Not aimless jokes, not empty ones. Jokes with a target and a point. Jokes that serve the larger bit, which is the show itself: a forum that protects the right to be funny about serious things without becoming careless about hurting people already hurting.

If there is a public statement attached to the return, it will likely live off-air—a post, a press note, a short video. The language will matter. “Apologize” is a word that can sound like capitulation to one tribe and like basic decency to another. A statement that says, “I regret the impact this had on people close to the tragedy” while reaffirming the right to criticize media narratives might be the only bridge that doesn’t collapse under either side’s weight. The contribution, if there is one, could be directed in a way that feels like support rather than surrender—a scholarship named for civil discourse, a grant to a newsroom project that teaches verification to teenagers. Money can make a point if you let it.

In the background, the production calendar is still penciled. Guests are being held. A big Friday musical act is “on soft” pending a green light. Writers have two versions of the next show’s opening—one with harder edges, one with a different rhythm that makes the same case more obliquely. Segment producers have warmed up evergreen ideas that can fill a block if leadership asks them to keep the opening short. That is what experienced teams do; they build contingencies like carpenters build braces, and they keep the set standing while the foreman argues with the city inspector.

There is a temptation, in stories like this, to pretend there is a pure solution: a return that satisfies everyone without asking anything from anyone. Television is not a pure medium. It is a collaborative, commercial art form wrapped in regulation and delivered through hardware built and maintained by companies that answer to shareholders and public commissions. The miracle isn’t that shows sometimes go dark. The miracle is that most nights they don’t.

If you are looking for villains, you can find them. If you are looking for grown-ups, you can find them too. They are often the same people on different days. An affiliate skeptic may be protecting a community standard. A comedian’s refusal may be defending the craft for the people who will come after him. A regulator’s stern talk may reflect a genuine concern about lines that matter most when pain is fresh. These explanations don’t cancel each other out. They make a difficult picture honest.

And then there is the central figure—forced by events to decide what a voice is worth. He can sign the papers, write the check, deliver the opening, and be back in your living room in days. Or he can hold out, wait for the temperature to fall, and risk being replaced by the idea of him—a rerun, a guest host, a new experiment that proves why late-night is so hard to replicate in the first place.

“You want him back on-air? Then you know what it takes.”

That line, recalled by a person who sat in one of the smaller rooms this week, isn’t a threat. It’s a shrug. It’s the way TV people talk when they’ve already made peace with the unromantic math of airtime.

The promise in the headline is simple: there is a real plan taking shape for a return, and the plan, as of now, depends on two conditions—public contrition and a financial gesture tied to the controversy. Whether those conditions are met exactly as presented, or nudged into forms that feel principled rather than punitive, will determine not just if the lights go on but how they feel when they do.

If the show is back next week, it will be because enough people decided the risks of darkness outweighed the risks of light. If it takes longer, it will be because someone in the chain believed that speech without restraint is not strength but carelessness. Either way, the audience will get what it clicked for: a clear picture of what “a seismic comeback” means in practice, not just in press releases. It means compromise measured in commas and semicolons. It means tone calibrated by people who understand that a word can do damage no punchline can fix. It means a star who knows that coming back is not the same thing as coming back unchanged.

And if the opening night arrives—if the band cues up, if the camera finds him, if the jokes land and the room exhales—there will be a brief second at the top, brief enough to miss, where he makes eye contact with the audience at home as if to say: we went through something, you and I and this show. We will keep going. We will be smarter about timing. We will not be softer about truth.

The rest will be television. The stage manager will start counting with her fingers. The cue card guy will smile because the punchline still works. A producer will finally sit down. Somewhere in the building, someone will turn the applause sign back on and, for the first time in a week, it will mean what it’s always meant—permission to let out what the room was holding in.