The Hilton Manhattan Midtown had the kind of light that made everything look expensive—votive candles flickering in glass cylinders, roses opening like whispers along a white‑runnered aisle, and chandeliers that turned the room into a field of captive stars. I stood at the center of it in a tuxedo that fit like an apology I wasn’t ready to make, a flute of Veuve in my hand, my new wife’s fingers tucked like a ribbon between mine.

Emily smiled at me with her photogenic dimples and the practiced softness of someone who had been told she was perfect since the fourth grade. She had a way of tilting her chin that made her diamond earrings catch the light, and when she did it tonight—our re‑wedding, as my best man kept calling it, as if the second time around needed a different word altogether—the cameras in our friends’ hands rose like a tide.

“David,” she whispered, leaning in so her perfume—orange blossom, something French and expensive—touched the rim of my glass, “you’re doing that thing with your jaw.”

I unclenched. I smiled the way men smile when the world is going their way. “This is the right thing,” I said, and I believed it just enough to hear it as truth.

Jazz slid through the hall, a brushed snare and lazy trumpet. White roses climbed the pillars, and the Hilton staff moved as if choreographed—black shirts, polished shoes, trays balanced like promises. I lifted my glass to the tables of clients and colleagues, to the uncles who’d flown in from Ohio and the cousins who’d come from Fort Lauderdale, to a scattering of venture capitalists who’d once told me I didn’t think big enough and had since learned to like my calls.

“Mr. Harris,” someone said over my shoulder, and I turned into the handshake of a Junior Partner who had been campaigning for Senior since April. Compliments, laughter, a joke about second chances, a tasteful toast about how love is better when you know how it can fail. I wore it all like a tailored coat.

Then I saw her.

She was in the shadowed angle between two ballroom doors, where the staff slipped in and out like ink lines, where the votives didn’t quite reach. Black shirt, sleeves to the wrist, hair twisted into the kind of knot you make with a pencil when you’re late for work. She held a tray of wineglasses, three lipstick stains already ghosting the rims.

My heartbeat stumbled, then pretended it hadn’t.

Anna.

My ex‑wife looked exactly like you don’t want an ex‑anything to look: composed without defiance, tired without surrender, beautiful in a way that has nothing to do with lip color or angles, and everything to do with the way a person stands when she’s carrying something invisible and heavy and insists on holding it herself.

For a breath, I was a man at a red light, watching the past cross the street. Then I laughed—a short, bright sound that didn’t belong to me.

“Hey,” someone at my table nudged me, the edge of his cufflink catching my sleeve. “Isn’t that your ex?”

“Life has a sense of humor,” another said.

“Fair, if you think about it,” a third added, the way men add things when they want to be on the winning side of a moment. “One person lands the deal, one person ends up pouring the drinks.”

I lifted my glass. “She never could hold on to things,” I said, and I felt the sentence land in the space between my ribs before it landed anywhere else.

Emily followed my gaze and then, in the way of those who know which stories belong to public rooms and which belong to the kitchen, squeezed my hand and looked away. “The band’s starting the Sinatra medley,” she said. “Smile.”

I smiled. And the night kept moving.

Thirty minutes later—maybe twenty‑seven, maybe thirty‑four; there’s the truth of a clock and the truth of a body, and they don’t always agree—the ballroom reached that warm pitch where every conversation is three conversations, where the server’s path becomes a narrow river and the dance floor seems to lean toward the feet that want it. Somewhere behind me a cork popped; somewhere to the left, a woman’s laugh bright as a fork against glass. I was pouring charm like bourbon when Robert Anderson—a man whose last name weighed as much as small banks—stepped to our table.

Robert had the kind of face you don’t forget even if you want to: slope of cheeks that made you think of wind, eyes that did not perform. He had shaken the hands of presidents, forgotten more balance sheets than I’d read, and in my industry, his approval opened doors that otherwise masqueraded as walls.

“David,” he said, and the way he said my name put a bit of winter in the August of my spine. He clasped my shoulder, lifted his glass. “You look happy. That’s rarer than money.”

“Tonight, sir,” I said, because men like him enjoy formality when everyone else has chosen familiarity, “I am both fortunate and grateful.”

He smiled in that thin way of men who know what they have and what it has cost. Then his gaze, unhurried as snow, drifted past me and puckered. There was a shift in the set of his mouth. He put his glass on the table without drinking.

“Excuse me,” he said, and the word wasn’t to me.

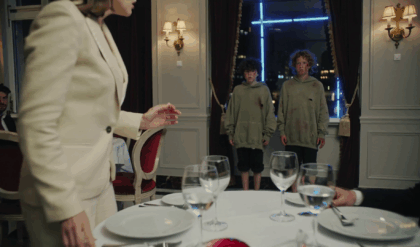

The band seemed to hesitate. The hiss of the HVAC cropped short, as if the room wanted to hear itself. Robert stepped into the aisle between tables, his voice lifting in a timbre that had surely steadied boardrooms and funerals.

“Ladies and gentlemen,” he said. “Forgive the intrusion, but there’s someone here who deserves—tonight of all nights—to be seen.”

Every head turned with the reflex of a school of fish. The room, which had been arranged around me, pivoted around the man who could buy my company three times over and still sleep. He pointed to the edge of the staff corridor, to the woman with the tray whose hair had come loose in two quiet strands.

“That woman,” he said, “saved my life.”

The sentence didn’t echo; it struck and sank. For a moment no one clapped because applause is something you do when you’re sure of your role in a moment, and this made no one sure of anything.

“It was three years ago,” Robert continued. “You’ll remember the storm that took out the lights from Yonkers to Montauk. My driver hit standing water on the Saw Mill, the car fishtailed, and we took the guardrail at fifty. We were in the river before I understood we had left the road.” His voice didn’t flinch. “By the time EMS arrived, I was hypothermic. I would not be in this room if a stranger had not waded in first.”

He looked at Anna as if she were an answer to a question no one had the right to ask. “She broke the back window with a tire iron. The driver got out by his own strength; I did not. She stayed under long enough that two bystanders thought she’d drowned. When she came back, she refused to leave me.”

Then he did what frightened me more than any of it: he bowed his head.

“Thank you,” he said to Anna. “I never found you. I did not know your name.”

In the space that followed, six things happened and I remember all of them in a way that feels like remembering a crash frame by frame: the bandleader lowered his trumpet; Emily’s fingers left mine; somewhere a waiter stopped with a tray of mini crab cakes and one slid, surrendered, onto the carpet; the room wobbled; I placed my glass on the table and it tipped without falling; and Anna—who had been a woman holding a tray in a ballroom—became the point of gravity.

She didn’t move. She didn’t forgive. She held the tray as if it could save her from a tide.

Robert turned once, slowly, toward me. “You must be very proud,” he said.

The line was open enough to walk in any direction: proud of the woman who had once been my wife, proud of the accident’s outcome, proud of being in the room where this was being said. Every direction led to a version of me I did not want.

“I—” I began, and the truth stumbled over every lie I had ever told about why we divorced.

“Mr. Anderson,” a voice near the bandstand called, breathless. It belonged to a man in a slim navy suit—the CFO of his philanthropic arm. He held an iPad to his chest like a missal. “There’s more.” He glanced at me, not unkindly. “Regarding the Riverside Fund.”

The Riverside Fund. The charity that had helped retrofit two clinics in the Bronx, that had funded mobile mammograms in Newark, that had, in a way that made donors feel good about themselves, translated money into the illusion of innocence.

Anna’s eyes flicked once—one flick—as if she’d heard a door open down a hallway.

“Three years ago,” the CFO said, “our records list an anonymous co‑founder who declined recognition in favor of… her spouse. It appears the anonymous co‑founder is—” He swallowed. He had the decency to be nervous. “Ms. Parker.”

The old story—the one where I am the architect of my triumph—lost a floor all at once, and then another. You could hear the rebar give.

Whispers aren’t a single sound; they’re a soft nation. They moved through the room like weather. Emily put a hand to her throat as if a necklace had tightened.

I felt something ancient shift in my chest, the way timber shifts before it cracks. “We built that together,” I said, to no one and everyone. “I put in the seed donation. I—”

“Mr. Harris,” the CFO said, and I hated the evenness of his tone, the courtesy of it. “The seed gift that initiated the Fund came from a private brokerage account in the name of Anna M. Parker. The larger public gift that followed was yours.”

The difference between first and larger is the difference between spark and gasoline. It is not nothing.

Robert didn’t look at me. Men like him don’t look at a man unraveling; they look at what deserves to remain.

I could have walked across the room then. I could have taken the tray from Anna’s hands and said a complicated sentence made of apology and history, something that began with I was wrong and ended with I am still learning how to be a man. I could have done a hundred variations of the only thing that might have made this evening less about one truth and more about two.

Instead, I stood in a suit that fit, among people who knew exactly which fork to use and when to use it, and I learned what a body means when it says: I trembled.

It wasn’t visible. My face did what faces do when they have been trained. But my hands, then my ribs, then the space behind my knees—each took a small, private quake. The glass on the table no longer looked like it held a drink; it looked like it held a way out.

Someone began to clap. It was late and awkward and exactly what happens when a room full of people needs a script. Ten others followed, then thirty, and the sound—meant for gratitude—filled with something that tasted like salt.

Anna dipped her head once, just enough to keep the tray from tipping. Her eyes found mine the way a lighthouse finds the same rock every night. Then she turned and disappeared through the staff door, her black shirt slipping into the seam of the evening.

After that, the night became a series of things people do when they are pretending a night is not already over. The band struck up “The Way You Look Tonight.” A bridesmaid cried for a reason she would name differently in the morning. A guest told a waiter, who was not responsible for anything, that the sauvignon blanc had gone warm. I danced with Emily in a circle that felt too small and said to her, quietly, “I’m sorry.”

“For what?” she asked, soft but not gentle.

“For not telling this story right,” I said. “For not telling it at all.”

Her breath touched my collar. “Do you love me?”

I thought of the rightness of the ring on her finger, of the way we fit on paper, of the months since our engagement during which I’d been lighter as if some invisible knapsack had been moved from one shoulder to the other. The question inside her question wasn’t whether I loved her; it was whether the story of us included a ghost I hadn’t acknowledged.

“I do,” I said, and I meant it the way a man can mean two things that do not agree.

When the room finally emptied, the roses smelled like something expensive gone slightly wrong. The air was full of leftover music. Staff wheeled out shelving with lipstick‑scarred flutes. I remained, as grooms sometimes do, in the middle of a place no longer ours.

I found the kitchen corridor without asking and followed it to a metal door with no name. On the other side was a working room: fluorescent hum, steam, the hot wet smell of dishwater and lemons. A woman in clogs called, “Behind,” as she slid past with a rack of plates. Near the sink, where a gray‑haired man used a sprayer that could take paint off a car, Anna stood with her tray empty, her hair loosening further into something that made my chest hurt.

“Anna,” I said.

She turned without surprise. “David.”

“You saved Robert Anderson.”

She looked at me as if I’d said, You once bought winter boots. “It was raining,” she said. “He was drowning.”

“You started Riverside.”

She shook her head a fraction. “I wrote an email to a friend who knew a lawyer who knew how to make a 501(c)(3). You wrote the check that made the brochure.” She pulled the elastic from her hair, retied it. “We started it the night your father called to say your mother’s biopsy was clean. Remember? You said, ‘Let’s do one good thing with our luck.’”

I did remember, and the memory was not an indictment. It was proof that I had once been a man who could locate goodness in ordinary rooms.

“I shouldn’t have laughed,” I said, and I learned then how small an apology can feel when it is true but late. “When I saw you. I—”

“You were happy,” she said. “Happiness makes people brave or careless. Usually both.”

The dishwasher hissed; a tray clanged; the hotel moved around us like a large animal in its sleep.

“Why are you doing this?” I asked, and I hated the way the question sounded, as if I wanted her to justify living.

She understood anyway. “Working?” She wiped a ring of water from the counter with the side of her hand. “Because the rent is due on the first. Because I like the rhythm of service—the way it’s busy and then it’s done. Because I spent a year sending résumés and another year learning that some people will always add the word divorced to your name even after they stop using the hyphen. Because I’m good at it.”

“You’re good at everything,” I said, which was less compliment than confession.

Anna’s smile was a corner thing that didn’t disturb the rest of her face. “Not at staying,” she said. “Neither of us was.”

“May I—” I started, and stopped. What? May I undo time? May I tell you I see it now? May I give you back your name on the brochure and ask you to accept it as if the ink were still wet? “I wanted to say congratulations.”

“For what?” She lifted her brows just enough to keep the question from being cruel.

“For surviving me.”

The elastic on her wrist snapped softly as she adjusted it. “We survive the stories we tell,” she said. “Toward the end we were telling the wrong one.” She glanced toward the swinging door, the one that kept the ballroom out of the kitchen and the kitchen out of the ballroom. “You should go. They’ll need you for pictures.”

“Robert—” I began.

“Will call you next week and say words like unfortunate and narrative,” she said. “He will still do business with you if his analysts say so. This isn’t a morality play; it’s New York.”

“Is there anything—” The sentence embarrassed me as soon as I made it: a man with the resources of a small country asking a woman washing glasses if there was anything he could do.

“Yes,” she said. “Stop making me your lesson.”

The flush in my face felt like heat coming off a car hood. “I’m sorry.”

“Be happy,” she said, but not as a benediction. “You picked it.”

I left the kitchen and found the place where the hotel becomes a hotel again. In the elevator mirror, the groom in the glass looked like a man who had been told a thing that would take a long time to finish telling him.

After the honeymoon—a tasteful four days in Cabo in which I learned that the ocean can look like an apology, too—life did what life does: pretended to go on. Emily moved through our apartment in that purposeful way she had, simultaneously making the bed and a case for a new portfolio company; I returned to an office with glass walls that reflected me back to myself in polite, flattered squares.

On Tuesday, Robert’s office called. The scheduled Thursday meeting was postponed. Analysts, they said. Liquidity windows, they said. The words were correct and still felt like a penalty.

On Friday, my assistant forwarded an email from a journalist whose byline had a habit of appearing next to verbs like Investigates and Exposes. She wanted to discuss the Riverside Fund and the narrative around its founding. Narrative is what people call the truth when they plan to sell it.

I typed a response. I erased it. I told my PR firm to say the words we always say when we want more time: mischaracterization, context, longstanding commitment to transparency. That bought us a week.

In that week I slept badly and remembered well.

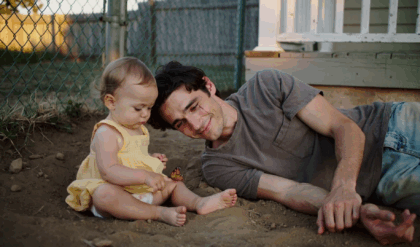

We had been young when we met—twenty‑six at a fundraiser for a bakery in Woodside that employed parolees, because that is exactly the kind of thing New York does on a Thursday. Anna had been wearing a blue dress the color of something I couldn’t afford. She’d argued with the keynote about whether the city’s idea of help ever looks like help at the kitchen table. I fell for the angle of her jaw and the way she said the word table as if it were the whole point of the world.

We loved like people who believed time was a partner. We made a home in a one‑bedroom on 83rd where the tub was too short but the light was generous. We learned the routes of each other’s hands. I learned the way she read—humming a little when she was happy with a sentence—and the way she put her hair up when she wrote emails that mattered. She learned my father’s laugh and my mother’s habit of apologizing to furniture when she bumped into it. We learned, toward the end, the way two people can be right about very different things and wrong about the same one: that love does not forgive neglect just because neglect apologizes after.

There had been a Thursday night, late, in that last year, when I’d come home carrying a laptop, a phone that would not stop buzzing, and the ruddy headache you get from flu‑light and adrenaline. Anna had set two plates on the table—soup and buttered bread—and I had eaten standing up while reading an email about a potential Series B that could change the way people thought of me. She had said, “Will you sit?” I had said, “I can’t.” She had said, “You keep saying that,” and I had asked her how long the soup had been on the stove, and she had said, “Long enough,” and that had been the whole problem.

It was easier to be right about time than to be right about love. We became very good at the first thing.

A month after the wedding, the Riverside Fund story ran anyway because stories like that always find the air. The headline was the kind that puts two truths next to each other and makes them fight: Anonymous Co‑Founder Was Ex‑Wife; Husband Took Public Credit. It wasn’t wrong; it wasn’t right. It was a mirror you don’t want to walk past because it might suddenly be clean.

We issued statements. We made quiet calls. The internet did what it does when given both goodness and blood.

“Tell me if you need me to say something,” Emily said one night, sitting cross‑legged on our sofa with a legal pad and a glass of Sancerre, her bare feet tapping the cushion. She was built for weather. She did not flinch. “I can write something from the position of the wife: we celebrate the work, etcetera.”

“I don’t want you to be in it,” I said. “I put you in enough already.”

“David,” she said, and there is a voice women use when they are practicing mercy. “I chose you.”

I kissed her. I climbed into bed. I dreamed in water.

In October, during a week when the sky sat closer to the buildings than usual, I took a walk along the Hudson without meaning to. I told my assistant I had a dentist appointment because that is what you tell people when you are going to do something that will not help the company but might help the part of you that keeps wearing your clothes.

I turned into a café I didn’t recognize, small, with the kind of chalkboard that makes you like the handwriting. The bell on the door was quiet as if it were recently taught manners.

Anna was behind the counter wearing an apron with the café’s name stitched into it in thread the color of toast. Her hair was in a knot again, but this one looked like it had been tied in a mirror. Beside the pastry case, a girl of maybe six or seven sat on a stool swinging her feet, a pencil tucked above her ear, drawing circles that grew into planets.

“Hi,” I said, because New York is small enough that this can happen, and because we had already met in the worst place to meet.

“Hi,” Anna said. She did not look surprised. “Tea?”

“Please.”

The girl looked up as if a street had told a joke. “Can I take his order?” she asked.

“You can write it down for practice,” Anna said. “But I’m still the one who makes the tea.”

The girl slid a piece of paper toward me with solemnity. “Name?”

“David.”

She printed it block by block, a builder of letters. “Order?”

“Green tea.”

“Okay.” She looked at Anna for the spelling of green. Anna mouthed it. The girl wrote GREN and then added an E that looked like it was leaning against the letter beside it. “I’m practicing taking orders. I’m going to be a person who owns a place,” she said. “Or a vet.”

“High chance of crossover,” I said. “A lot of pastry owners have dog customers.”

She considered that. “That’s true.” She tucked the pencil behind her ear again like a woman half her size who knew which tools belonged where. “Do you work?”

“Yes,” I said. “I build companies.”

“What do they do?”

“Try to make something useful.”

She nodded as if that passed. “I’m Ruby,” she said. “I’m here on Tuesdays and Thursdays after school and Saturdays until noon.”

“Hi, Ruby.”

She went back to her circles. “My mom says people should say thank you more,” she added without looking up.

“She’s right,” I said. “She usually is.”

Anna placed the tea on the counter, the cup clean and white and heavier than it looked. “On me,” she said.

“I can pay.”

“You can. And you can let me do this the way I want to do it.”

We stood there with the kind of silence that has to learn which path it will take: the one that kills what’s left, or the one that leaves the door unlocked.

“Ruby’s yours?” I asked, not because it mattered and not because it didn’t. Mostly to know whether the world had made a shape I should recognize.

“She’s mine,” Anna said. “She’s also her own.”

“Of course.”

“She likes stars,” Anna added. “She draws them in circles so they don’t fall.”

“That’s smart.”

“It is.” She nodded toward the table by the window. “You can sit if you want. Or you can take it to go and we can pretend this was the kind of encounter that doesn’t ask anything else of us.”

“I’ll sit.”

I took the table by the window and watched the river pretend to be a road. Ruby drew with concentration that made the rest of the café quieter, the solemn intensity of a child allowed to become herself in small, daily ways. Anna wiped a table with slow thoroughness, as if care itself were a cloth.

When they were not busy, she came to my table and stood without sitting, the apron string making a bow at her hip.

“Do you need me to sign anything?” she asked.

The question grazed my pride until I recognized it as history. After divorces, paper is the language people think they can understand. “No,” I said. “No paper.”

“Good,” she said. “I’m better at dishes.” She watched the street where a taxi seemed to be arguing with a delivery bike about ownership of a lane. “I don’t want anything from you, David.”

“I know.”

“I want you to know I’m okay.” She didn’t say it like consolation; she said it like a weather report. “You were afraid I wasn’t. That’s fair. You didn’t have any new information.”

“I had a story,” I said.

“We both did.”

Ruby came over and set a small plate near my cup. On it was a shortbread cookie with a dimple of jam that looked like a thumbprint. “It’s for free because you’re new,” she announced. Then, as if checking my credentials, “Do you know what gratitude is?”

“I’m trying to,” I said.

She approved of that. “Good.” She went back to her planets.

“I laughed,” I said to Anna. “At the wedding. It wasn’t about you. It was about an idea of you. That’s worse.”

“Yes.” She didn’t lacquer it. “It is.”

“I think I was relieved,” I said. “To be the person who had landed on the side of the story where things look shiny. I forget sometimes that shine is just light pretending to be skin.”

Anna almost smiled. “You always were good with metaphors. Remember when you said love was a houseplant and then killed mine by overwatering it?”

“I do.”

“You weren’t wrong,” she said. “It was just the wrong plant.” She lifted my empty cup. “Another?”

“Please.”

Later, when the café emptied into the long exhale between lunch and the after‑school rush, Anna sat across from me and folded her hands as if she were about to say grace. “He wrote me,” she said.

“Robert?”

“Yes. He said the thing powerful men say when they don’t want to make it worse: Tell me what you want, and I will listen. I told him what I wanted was three MRI machines in three clinics, paid for with money that doesn’t have anyone’s name on it.”

“That’s… good.”

“It’s sufficient,” she said. “Good is something else.”

“Do you need—” I caught myself. “Would you like my help?”

“I’d like you to keep doing work that, if your name were taken off it, would still be the work.”

I absorbed that. It fit like the suit had. “I can try.”

“You can,” she said. “Trying is the only thing that gets done.”

When I rose to go, Ruby came to stand by her mother, her hand finding the apron string. “Do you work far?” she asked me.

“Sometimes,” I said. “Sometimes I work inside my head.”

She considered that with suspicion. “You should have a place where you can stop and then be done.”

“I should.”

She looked up at Anna for confirmation that she had given good advice. Anna nodded. “He should.”

On the sidewalk, the air had that clean, metallic edge the city gets when the wind comes off the river. I walked six blocks without checking my phone and then realized I had been holding my hands the way you hold something fragile and invisible, and I let them fall.

At home that night, Emily watched me watch the news, then muted the television. “You look like you’re finishing a sentence,” she said.

“I might be starting one,” I said.

She took my hand and turned it over as if reading a map. “I knew who you were when I said yes, David.”

“I didn’t,” I said.

“We’re not in trouble,” she said, which is what you say when you can feel the air looking for a fight and you’d rather it didn’t find one. “We can be good.”

I believed her because she had that way of telling the truth that makes it sound like a plan.

Winter came. Riverside funded three MRI machines with money that arrived in envelopes with no return address. My company closed a smaller deal with Robert’s firm than we had expected, on terms that were fair and not flattering. The story about the Fund moved to page three of the internet and then to page eight. My mother called to say she liked Emily and that I had always been stubborn in ways that made prayers useful.

In February, I went back to the café. The chalkboard said: Today, Be Kind to the Person You Are On Mondays. Ruby had made a paper solar system that swung gently above the pastry case as if the whole universe had consented to baked goods.

“Hi,” Anna said. “You look less like a headline.”

“I feel less like one,” I said. “I wanted to tell you…I told the board we’re changing the press language on Riverside. We’re not going to correct the old articles, but we’ll stop telling the half of the story that made me larger.”

She nodded. “You can only edit forward.”

Ruby peered over the counter. “You came back,” she said, the way you say a fact you hope is a promise.

“I came back.”

“Good,” she said. “We have a new cookie. It’s called gratitude.”

“What’s in it?”

Anna smiled. “Butter and patience.”

I bought a dozen. I carried them home in a white box tied with red string, and Emily and I ate them at our kitchen counter, and for the first time in a long time I felt full in the place hunger usually hides from elegance.

This is not a story about redemption. Not exactly. I did not become a man who sold all his things and moved to a house with a porch and learned to fix his own roof. I did not donate the portion of my wealth that would make me brave enough to use words like vow and forever without tasting their metal.

This is a story about a room, a river, a kitchen, and a café. About a woman who saved a man because he was drowning and then saved herself because she was not. About a girl who drew circles around stars to keep them from falling. About a groom who trembled and learned how to hold his hands when he did.

Once, at a party with chandeliers, I laughed. Thirty minutes later, the truth found me with a finger on my chest and said: you are not the only protagonist here. The tremble was not punishment; it was an instrument, a tuning fork struck against the bone. It let me hear where I was out of key.

Sometimes, when the city is kind and the river looks like a road again, I stop by the café just before closing. The bell is always polite. Ruby packs me a cookie, and Anna pours me tea without asking which kind I want as if she trusts me to drink what I’m given. We talk about small things that are really big: whether to salt pasta water like the sea; whether gratitude is a practice or a weather pattern; whether the subway will ever learn to stop being late for itself. I pay. I leave tip money heavy enough to feel like respect, light enough to feel like nothing at all. I walk home holding a warm cup on a cold night.

There is a way to hold a cup that warms your hands before you drink. I have learned that way. When I lift it, I think of the invisible weight people carry and the visible ways we can help. I think of a woman in a black shirt who stepped into a river because she could. I think of a girl drawing circles around stars so they won’t fall. And I think of the version of me who finally understood that the measure of success is not what you stand in front of, but who you are when you step into the kitchen and say a person’s name without asking her to be anything other than herself.

When I finish the tea, the cup leaves a small ring on the table. I wipe it with my thumb and don’t mind the stain it makes. Some marks don’t need to be polished out. They need to be seen, and then lived with, and then used as the place where the next cup goes so you can make a kind of map of where you’ve been.

At my re‑wedding, I laughed. Thirty minutes later, I trembled. A year after that, on an ordinary Thursday, I said thank you to a woman who didn’t need it and said you’re welcome to a man who finally did. And then I went home and kissed my wife and told her the story again the right way—the whole way—so it could stop being a headline and become what it was supposed to be all along: an ordinary, human truth that fits in a cup, warms the hands that hold it, and tastes, at last, like something I will spend the rest of my life trying to deserve.