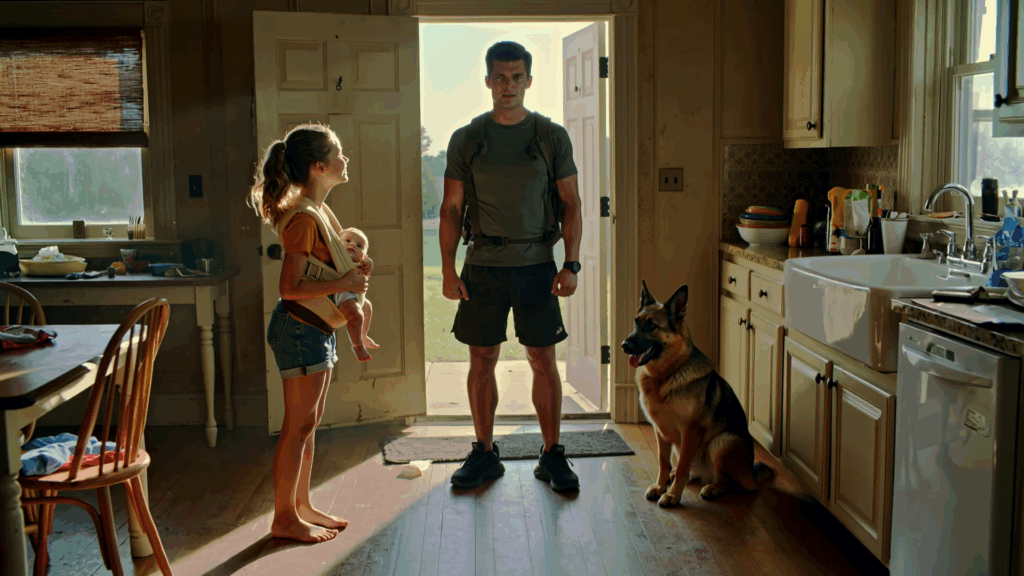

The autumn air in Virginia carried the scent of burning leaves when Staff Sergeant Daniel Hayes finally stepped off the bus. His uniform was pressed but faded, his boots worn from the desert sands of Afghanistan. He had been gone for nearly two years, counting the days until he could see his family again. Yet when he reached the small house on Oakwood Street, what greeted him was not the warm embrace he had built in his head during long nights on a cot, but something that made his stomach twist.

The front yard was unkempt, grass grown too high, the mailbox stuffed with old flyers and a rain-warped church bulletin. On the porch sat his nine-year-old daughter, Emily, with her arms wrapped around her younger brother, four-year-old Joshua. Beside them, a broad-chested German Shepherd—Max—stood with ears canted forward, head high, the way a sentry in a strange land keeps watch when tired men sleep.

“Daddy?” Emily’s voice cracked as she leapt up, tears rushing down her cheeks. Joshua followed on small, determined legs and collided with him, a soft thump of child against canvas. Daniel dropped his duffel and wrapped them in his arms. Sand and Virginia soil, cedar aftershave he guessed he no longer owned, their shampoo that smelled like apples, all of it turned into a single breath he wanted to hold forever.

He looked past their shoulders toward the screen door and felt the ghost of a life he’d planned press against the glass. “Where’s Rachel?” he asked. He already knew his question was a mistake; the air changed around it. A bird hopped along the porch rail and flew off as if it understood.

Emily lowered her gaze. “She’s gone, Daddy. She left… a long time ago.”

The words hit with the same silent force as the blast that had once thrown him into a ditch outside a walled compound. Rachel had promised she would hold the home together—pack lunches, braid hair, read bedtime stories—while he finished his last deployment. They had married too fast after grief and loneliness met at a crossroads. Kate, the children’s mother, had died from an aneurysm the summer Emily turned seven. The house had grown quiet in a way he still didn’t know how to describe, and the silence had frightened him as much as any night patrol. Rachel brought laughter at first. Or maybe she filled a shape he needed filled.

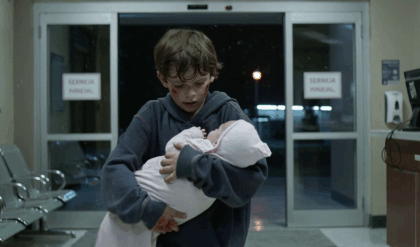

“She went away with some man,” Emily said, and the steadiness in her voice frightened him more than the words. “She didn’t come back. I had to take care of Joshua. Max helped me.”

Max pressed his flank against Joshua’s knee as if to sign the statement. The dog’s coat was darker than Daniel remembered. Or perhaps Daniel remembered wrong—war recolors everything. He nodded once, not trusting his throat, and ushered the children inside.

The refrigerator hummed with the kind of effort that suggests it intends to fail soon. Inside: milk, three eggs, a bottle of ketchup, half a jar of grape jelly, and a shapeless bag of lettuce browning at the edges. The sink held a pile of dishes washed by small hands. The soap scum and the way the plates leaned made a catalog of effort. On the counter: past-due envelopes, a pink slip from the power company with red letters marching across it, a foreclosure warning in an officious font he had seen before in the hands of other soldiers too proud to ask for help.

He set his palm on the stack to still the panic it tried to feed. Then he turned and knelt so his eyes were level with Emily’s. “Did you tell anyone?”

“I told Mrs. Whitaker next door. She brought us food sometimes. But I didn’t want anyone to take Joshua.” Emily’s chin trembled, and her hands twisted the hem of her too-small T-shirt into a rope. “I’m sorry I didn’t tell you. I didn’t know how.”

“There’s nothing to be sorry for,” he said, and he meant it with a ferocity that startled them both. “You did more than anyone could ask. I’m here now.” He looked at Joshua. “Buddy, you okay?”

Joshua put two fingers in his mouth and nodded, then leaned into Max, who tolerated the weight with patient dignity.

That first night, after he made scrambled eggs and jelly toast and found a clean pair of pajamas for Joshua and one of Kate’s old, soft T-shirts for Emily, after he read two stories with a voice that felt new in his own mouth, after he stood in the hallway and listened to them breathe, Daniel sat at the kitchen table and stared at the peeling paint near the window. His hands were shaking. Not the tremor he had willed into stillness in the field when he needed to steady a rifle; this shake came from a different place. The dog lay across his boots as if they were twins set down in a cradle.

He wanted to believe anger would carry him far. Anger is a fuel in the short run. But the long road always demands something less dramatic and more difficult. He reached out and scratched Max behind the ear, the way Kate used to, and the dog’s eyes softened with an old familiarity.

In the weeks that followed, he built a life the way you build a fire when everything is wet: slowly, with patience, coaxing whatever will burn into a flame. He called his old first sergeant, who put him in touch with a reintegration officer. There was a small stipend he could apply for, a contact at the VA hospital in Richmond, a group therapy schedule taped to the fridge with a magnet from a Myrtle Beach souvenir shop. He drove his children to school in the old Ford, a truck Kate had bought used and called “Betty.” He sat down with the principal, Mrs. Feldman, who had a tight bun and a kinder heart than her appearance suggested. “Emily is exceptional,” she said, and the word exceptional hurt. “She reads at a high school level. She’s… she’s had to be strong.”

He clenched his jaw. “She won’t have to be the parent anymore.” He said it as an order to the universe.

The night shift at a shipping warehouse off Route 1 came with a neon vest and the relief of honest fatigue. The foreman’s name was George Pickett—people called him Picket Fence—and he had a generous laugh that rang off loading docks. “You military?” George asked on the first night, glancing at Daniel’s boots and the way he folded his lunch bag into a neat square. When Daniel nodded, George shrugged as if that solved several problems. “Good. I like men who know how to show up.”

Show up. Two words that separated him from the version of himself who had let grief and fear steer him into a marriage he did not understand. He showed up at home before dawn with donuts once a week. He showed up at school events. He taped Emily’s science fair flyer to the fridge. He learned the names of Joshua’s stuffed animals without correcting their grammar. He learned that Max slept lightly and positioned himself between the children and the door as if he’d read a manual on house defense.

At night, though, when the house was quiet, the war returned in images that had lost their edges but not their power. There was the alley in Khost where a boy sold oranges from a blanket. There was the bright pre-dawn when distant thunder wasn’t thunder. There was a bracelet made of colored thread that a girl had slipped over his wrist in a village that had no name he recognized. He caught himself reaching for it when the fear rose, but Kate had taken it off the day Emily was born because it snagged on the receiving blanket, and he’d put it in a drawer to keep it safe. He found it there now, tucked under a roll of tape, and tied it around a pipe under the kitchen sink. He didn’t tell anyone why.

The neighbors filled gaps in ways that felt like kindness and, once in a while, pity. He took the kindness and gave back where he could, cutting a fallen limb for Mrs. Whitaker and fixing a loose shutter for a young couple who both worked at the hospital. The church down on Miller’s Road sent a casserole and then, when he returned the dish, a bag of hand-me-down clothes that smelled like detergent and someone else’s childhood. A woman named Lila from the clinic down by the Kroger stopped by with pamphlets about nutrition and local resources and spoke to Emily like a person, not a problem to be solved. When she left, Emily said, “I like her,” in the voice she used for books she read twice.

Emily asked him one evening while he was mending the front fence with a hammer that had belonged to his father, “Are you going to leave again?” She said it like a scholar posing a question about stars but with fear that belonged to a different age.

He dropped the hammer and took her shoulders in his hands. “No. I will not leave you.” Then, because promises sometimes need more than words, he said, “I can’t promise the world won’t try to take me away. But I can promise it will have to kill me first.” He smiled when she made a face at the dramatic part. “I’ll be right here.”

She nodded and looked past him, past the fence, toward the neighbor’s yard where Max had decided a squirrel needed formal surveillance. “I kept the house together,” she whispered suddenly. “I made lists. I did laundry on Saturdays. I learned how to make pancakes that didn’t look like comets crashing.”

He pulled her in. “You saved us,” he said. “But you don’t have to save us anymore.”

They developed a rhythm that felt like a song played by someone who had learned only three chords but meant every note. Morning: cereal, coffee, the hiss of the shower when the water heater tried to keep up. Noon: school, preschool, the sound his truck made when the muffler sighed at stoplights. Night: dinner at the small kitchen table that had a notch from when Joshua had banged a spoon too hard as a toddler, homework with Emily while Joshua colored, bedtime, a walk in the dark with Max at his heel.

He found Kate everywhere in the house: the curve of a ceramic bowl; a small handprint in pale paint on the wall behind the laundry room door; the box of Christmas ornaments labeled in her neat schoolteacher handwriting; a recipe card for blueberry muffins in the drawer with the aluminum foil. He spoke her name aloud one night when the children were asleep. It didn’t break him. It stitched a seam that had been open too long.

Rachel returned on a Wednesday when the air had begun to smell like rain. Emily had made a collage for school of “things that hold us up”—a photo of a bridge, a feather, a chair, Max. She was gluing a picture of their house onto poster board when a black sedan pulled to the curb with the nervous energy of something that belonged more to a strip mall than a neighborhood. The door opened and Rachel stepped out in a jacket that tried too hard.

Max stood. The sound he made was low and intimate, the way an engine makes a promise no one wants fulfilled.

Rachel lifted a hand like a flag of truce. “Danny,” she called, using a name he’d abandoned years before, the way someone might stand on the wrong side of a river and pretend they were always on the right one. “Kids.” She smiled the way people smile at babies in grocery stores. “I came back.”

Joshua went to Emily so quickly his shoes squeaked. Emily held her brother and didn’t move. Daniel stepped onto the porch and set his palm against the door as if it were a person. He didn’t look at Rachel’s face first; he looked at her hands. No ring. A new manicure and the kind of tremor that means too much caffeine or too much fear. Or both. The man she had left with wasn’t there.

“You made a choice,” he said. He heard a steadiness in his voice that surprised him. “You left children alone. Emily raised Joshua while you were gone.”

“I wasn’t happy,” she said in the tone people use when they think unhappiness is an argument that erases harm. “I made a mistake.”

Emily stood there, Emily who had made pancakes and had learned to count bills at the Kroger checkout and had cried quietly in the pantry when Max had been sick once and she’d thought he might die. “We don’t need you anymore,” she said. The words came out gentle, which made them heavier.

Rachel’s chin trembled. “I’m their mother.”

“No,” Daniel said, and he didn’t raise his voice. “You married me two years after my wife died because I was a man drowning who thought a boat was a boat.” He shook his head. “You left. Stepmother is a job you quit.”

She looked at the papers tacked to the cork board inside the entryway as if they were an exam she had to pass to be allowed back in: the children’s school calendar, his schedule, the therapy group flyer with a simple list of times and a phone number. “I can help now,” she said.

He closed the door gently. He made sure his hand didn’t shake until it met the doorknob on the inside.

The knock that followed had the rhythm of someone who believes persistence is a personality. He didn’t open it.

Rachel called three days later. He answered because sometimes mercy is making a thing said instead of letting it live in the brain as speculation. She wanted money. Not much, she said, just a “little help.” The man she left with—Evan—had left her. The world had been unkind. She had debts she framed as weather. “You owe me,” she said finally, and he could hear the naked hunger under the pretty words.

“I owe my kids,” he said, and ended the call.

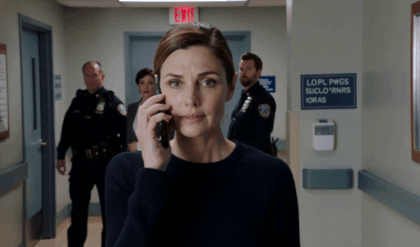

What followed was the kind of petty war that people wage when they are losing bigger ones. Rachel called Child Protective Services and said the children had been left alone. She framed herself as a whistleblower. A social worker named Yvonne Carter came by in a gray sedan with a clipboard and a face that had seen everything and forgotten none of it. Daniel invited her in and introduced her to Emily and Joshua as if this were a dinner guest. He made coffee and put plates on the table for the peanut butter cookies Mrs. Whitaker had sent over. Yvonne sat and asked questions in a calm, low voice. Emily answered with respect and the kind of crisp detail that comes from telling the truth.

“Did you ever leave your brother alone, Emily?”

“For like five minutes once when the smoke alarm went off because the oven got smoky and I had to open the door,” Emily said. “But I could see him from the front door.” She lifted her chin. “I made a list called ‘fire plan’ after that.”

Yvonne glanced at Daniel. “And did you inform the school when you returned, Mr. Hayes?”

“I met with the principal the next day,” he said. “I also called you.” He nodded at the card she had given him when he’d walked into the CPS office and asked how to make sure no one thought he was hiding anything. It had startled the young receptionist. It had disarmed Yvonne.

Yvonne walked through the house, touched the refrigerator and took note of the food inside, looked into the bedrooms, met Max in the hallway and said “Hey, handsome” in a voice that suggested she’d known a few dogs who had kept children alive in bad times. At the door, she turned to Daniel. “If anyone calls you again,” she said, “ask for me by name.” She paused and added, “You did right, coming to us first.”

The foreclosure notice didn’t care about truth, only math. He sat at the kitchen table with a stack of bills that felt like a biography written by a stranger pretending to be him. There was a program for veterans that might pause the march of numbers; there was a woman at the bank named Trish with a drawl that turned hard when she spoke about policy and soft again when she spoke about her father who had been Navy back when ships had names that sounded like promises. “Make three consecutive payments,” she said, “and we can talk about a modification.”

He did the math. It was not beautiful, but it was possible.

George shifted his schedule to give him overtime. “Don’t make me regret this,” he said, but his grin said he already knew he wouldn’t. Daniel took the Sunday shifts that other men with small children avoided. He slept in the truck on his break and woke with his neck cramped but a sense that each ache meant an inch won.

Emily’s science fair project transformed the kitchen into a lab. She built a model of a bridge out of craft sticks and string and wrote a paper about tension and compression that made Daniel want to call Kate’s old teacher friends and read it aloud. One night Emily asked if bridges were built more by math or by belief. He laughed and said, “Yes,” and she rolled her eyes and called him unhelpful—and then sat up half the night and wrote a paragraph that made a case for both. Joshua made a bridge of crayons on the floor for his cars and called it “the most important road.” Max honored it by stepping over.

The Saturday before the fair, Evan Crane showed up. He wore a shirt that believed it was more expensive than it was and a beard that was supposed to make him look older and steadier than his eyes allowed. He stood on the sidewalk with a casualness that rang false, a hand in his pocket and his weight tipped just so. “You Daniel?” he called. He said the name like a dare.

Daniel felt that old calculation turn on in his brain, the one that measured distance and light and the angle of a thing thrown. “You’re on my curb,” he said.

Evan smiled without moving any muscles that matter. “Rachel says those are her kids, too.”

“Rachel says many things,” Daniel replied. “Do any of them end with her doing dishes?”

Evan laughed like a man who wanted credit for having a sense of humor about the harm he carried. “She needs a little help,” he said, and the cantor of his voice suggested he’d defaulted on a lot of ‘little helps’ and had learned to make the ask anyway. “She told me you’ve got a house equity situation. Might be smart to sell before the bank—”

Max walked between them and sat. He didn’t growl. He just looked up at Evan the way a judge looks over reading glasses.

“Leave,” Daniel said. “You’re scaring my dog.” He smiled when Evan glanced down, unsure which of them the joke belonged to. Evan left with the swagger of a man who didn’t know he had already given away the one card in his deck.

A week later, a rock came through the front window at midnight. It didn’t hit anyone. It hit the wall and knocked a picture off, a photo of Kate in a field with Emily on her shoulders and Joshua inside her belly like a secret not yet told. Max hit the door before the sound of the glass had finished. Daniel was behind him.

He didn’t chase. He didn’t run. He stood on the porch in his T-shirt and bare feet and listened. Night bugs chattered. A car engine coughed to life around the corner and revved too loud. He memorized the sound the way men memorized the faces of those they’d owe or those who’d come to collect.

The police came and took notes and wrote things down and nodded at the dog and at the soldier’s steady breath. An officer with a young face said, “You’re Hayes? You’re the one who got the city to fix the stop sign on Oakwood.” Daniel nodded. The young officer glanced at Max. “Good dog,” he said, and then to Daniel, “Get a camera.”

He did, the next day at Walmart, and he set it up with a YouTube video and the kind of stubborn patience war had taught him. He also called Yvonne and told her what had happened, and she said, “Thank you,” as if he were helping her, too.

The call from the bank came on a Tuesday afternoon when the light through the kitchen window had the thinness of late autumn. “Mr. Hayes, this is Trish,” the voice said, and he could tell from her tone that whatever followed would contain both bad and good. “You made the payments. I pulled a few strings. We can pause the foreclosure process. Keep doing what you’re doing.”

He hung up and held the counter with both hands, his head bowed. Emily came in and asked if he was praying. “Sort of,” he said. “Tell Mrs. Whitaker I’ll fix her porch step on Saturday.”

The therapy group mattered in ways he didn’t expect. He sat on a metal chair in a church basement next to men who looked like garbage men and bankers and a woman who ran a landscaping business and had two tattoos of birds barely visible under her sleeves. They all had their own deserts. They said small, difficult things. He said, “I was afraid I’d be useless at home,” and a man named Sykes, who had a voice like a shovel, said, “You are not a weapon. You’re a tool. Tools build things.”

He took the words home and sanded them smooth and set them where he could see them.

Emily won second place at the science fair. She was furious, which made him proud, because her fury was about precision and not about some idea that the world owed her first place for all the ways it had taken other things. They celebrated with milkshakes at the diner off the highway that had red stools and a waitress who called everyone honey in a way that never felt lazy.

Winter came with a clarity that sharpened the sound of everything. The camera on the porch caught Evan twice in the same week driving by at odd hours. Daniel brought the footage to the police, and the young officer, whose name turned out to be Delgado, said, “We’ll swing by more often.”

Rachel filed for visitation. Trish from the bank told him in a voice that meant kindness dressed up as business, and Yvonne called, and then a volunteer lawyer from the veterans legal clinic at the university sat with him under fluorescent lights and explained words he thought he understood—custody, guardianship, abandonment—and what they meant when translated into paper. “The judge will want to know what stability looks like,” the lawyer said. “So show them.”

The day of the hearing, he woke before dawn and ironed his shirt. Emily stood in the doorway and watched him work the board like a man building a small house. “Do I have to talk?” she asked.

“Yes,” he said, and the yes hurt him. “But only what you want to say.” He tied a tie and noticed his hands were steady. Joshua wore a small blazer that had once been part of an Easter outfit. Max did not go to court. He watched them leave with the offended dignity of a king not invited to his own counsel.

The courtroom smelled like old books and new coffee. Rachel sat at the far table with a lawyer in a suit so shiny it seemed to hum. She wore a blouse that shouted and a face that tried to whisper regret. Evan was not there. Daniel sat with his lawyer, who had a hairline in retreat and a smile like a welcome mat that said “Wipe Your Feet.”

When the judge asked questions, Daniel answered like a man describing a bridge he had built with his own hands: this plank, this nail, this rope. He told the court about school drop-offs and the science fair and Joshua’s fear of the dark and the list Emily had made called “fire plan.” He did not talk about war. He talked about pancakes. He talked about shoes sorted by the door. He said Kate’s name once and Rachel flinched as if someone had thrown a rock from very far away and somehow still hit the window she lived behind.

Emily spoke. Her voice shook and then didn’t. She talked about the morning she had realized the milk was gone and the time Mrs. Whitaker had taken them to the dentist and the night she had moved a chair under the door because she didn’t trust the lock. “Max slept there,” she said, “and he only growls when he has to. I counted twice.”

Rachel said she had been overwhelmed. She cried at the right times. She said she had seen a therapist, which might have been true. She said she loved the children. The judge’s face did not change.

In the end, the court granted Daniel full legal and physical custody. Supervised visitation was offered to Rachel provided she enrolled in counseling and paid child support—numbers that made Rachel blanch and then look over at Daniel as if he could save her from arithmetic. He did not meet her eyes.

Outside the courthouse, Emily stood under a patch of winter sun and let it warm her cheeks. “Can we get hot chocolate?” she asked, like a child who had done something brave and was willing to be a child again if the grown-ups would do their part. They did. Joshua spilled his on his sleeve and laughed, and Daniel didn’t tell him to be careful. He handed over napkins and said, “Good thing sleeves have ends.”

A week later, Evan broke into the house at two in the morning.

He chose the back door and a screwdriver, which told Daniel things about what Evan knew and didn’t. The camera caught the first shadow. Max heard the second. The sound he made brought Daniel fully awake from a dream in which he had been walking a road that never stopped turning.

Daniel moved like a man whose body had rehearsed. He took the baseball bat from the closet—no guns in the house, that had been a promise to himself since Afghanistan—and stepped into the hallway. Emily stood in her doorway, eyes wide, her hand on Joshua’s shoulder, both children quiet because they had been taught something you can only teach by living it: the difference between panic and a plan.

The kitchen door opened. Evan’s breath came in hard, eager pulls. He was not a man who understood silence. Max stood between the intruder and the hallway, hackles raised, not barking now. Daniel said, “You need to leave,” and the strange thing was how calm he sounded.

Evan lunged toward the counter where the keys often sat. They weren’t there—Emily had moved them weeks ago to a hook inside the pantry because “people in movies always look for keys on counters.” Max moved first, a blur and a sound that was all warning turned to action. Evan screamed, not high but small. He dropped the screwdriver. Daniel didn’t swing. He held the bat low and said, “Down,” and Max backed away, standing guard, a wall that breathed.

The police came fast because Delgado had put a note on the nightly patrol, and the sound of sirens was, for once, a relief. They took Evan away with a bandaged forearm and a face that had discovered a limit. Delgado stood in the kitchen and looked at the dog, then at Daniel. “Good dog,” he said again, and then to Daniel, “You should think about getting him certified. Therapy or protection, either one. He’s a pro.”

The house felt different after that night, not haunted but claimed. Daniel fixed the door and replaced the window and, because sometimes rituals matter, they ate pizza on the floor in the living room and watched an old movie Kate had loved about a man who builds a field because he believes men will come. Emily cried at the part where the dad plays catch. Joshua fell asleep with cheese on his chin. Max lay with his head on Joshua’s foot and kept one eye open as if the world might try one more time and he would be ready.

Spring snuck in with green on the trees behind the shed and a softness in the air that made the mornings smell like wet earth and possibility. Daniel started running again, slow at first, then faster, his feet learning the neighborhood like a poem. He waved to Mr. Whitaker and to Lila from the clinic and to the man who ran the pawn shop and to the teenage boy who spent long afternoons dribbling a basketball at the end of the cul-de-sac, practicing a crossover that would take him out of this block or keep him here forever, both of which could be a mercy.

At work, George’s boss noticed how Daniel handled a minor crisis when a truckload of pallets broke and the forks jammed. “You want days?” she asked, and then, because he looked surprised, “You fix things. I like men who don’t just point at fires.” Days meant dinners at home and bedtime stories without red eyes. It also meant less overtime, but by then the bank had shifted his mortgage to a manageable number, and Trish had sent a note that said “Keep going” in handwriting that could fill a recipe card.

Emily joined the robotics club. The teacher in charge, Mr. Chen, had the gentle intensity of a man who had loved Lego before it was a brand. He handed Daniel a list of parts and a calendar. Daniel learned more about stepper motors than he would ever need in any other life, and he didn’t mind. He soldered tiny joints at the kitchen table and thought about how bridges and robots and fatherhood were all the same problem in different shapes.

Joshua learned to ride a bike. He fell twice and, both times, looked up and said, “Did the ground move?” Daniel told him yes, sometimes the ground moves.

Rachel called once more. “I’m leaving town,” she said. “Evan’s got a cousin in Florida.” He waited for the ask and it didn’t come. “Tell the kids I’m sorry,” she added, and he said they knew and didn’t say what they knew. He hung up and didn’t feel the relief he had hoped for or the sadness he feared. He felt a small hole in the air close.

They painted the living room a soft gray. Emily chose it from a swatch book because it made the white trim look like a sentence that had been checked for grammar. They ate on the porch on warm nights. They planted tomatoes. They trained Max to fetch the mail from the gate and to bow on command because Joshua thought bowing was what heroes did after saving a kingdom and Max—because he was a dog—agreed readily to new definitions of honor.

On Memorial Day, they went to the park where the town had placed names on a wall. Daniel ran his finger over the letters of three men he had known and one he had only met once at a briefing, a quiet man with a scar under his eye who had told a joke about coffee that no one had understood until much later. Emily and Joshua stood still without his asking them to. On the way home, Joshua said, “Do you miss your friends?” and Daniel said yes and that he kept missing them the way you keep loving someone who won’t come back.

Yvonne came by in June to close the file. “You’re okay,” she said, and her smile had the professionalism of a note entered into a system and the warmth of someone who had allowed herself to care. “Call if you need me.” She crouched and petted Max. “You take care of them,” she told him. Max licked her hand as if signing a contract.

There were still nights when fear moved through the house like a draft. There were mornings when the light fell just so on Kate’s recipe card and Daniel had to put both hands on the counter and breathe. There were bills and the muffler still made that noise and the dryer sometimes forgot its purpose. But there were also the two notes Emily had taped to the inside of the pantry door: “Do Not Put Keys on Counter,” and underneath it, smaller, “You’re Doing Great.”

One afternoon late in summer, Daniel took the children to the Shenandoah. They hiked a short trail and sat on a rock that looked out over a valley spread like a quilt stitched from fields and roads and the river like a ribbon someone had set down carefully. Emily asked him about their mother. He told stories he hadn’t known he remembered—the way Kate laughed when she burned toast, the time she tripped over Max because he had fallen asleep in the laundry, the day she had taught Emily to whistle and the whistle had sounded like a kettle begging for mercy. He told Emily that love could end in a heartbeat and that this was not a reason not to love.

“Did you ever think you couldn’t do it?” Emily asked. Her hair had grown out and lay over her shoulders like a small promise someone had remembered to keep.

“Yes,” he said. “But then you made a list.”

She rolled her eyes and then she grinned and then she cried and they did not call it crying. Joshua threw a stick and Max brought back a different stick and somehow this resolved the moment.

School started again and the first-day photo showed Emily taller and Joshua with a missing front tooth and Max in the background pretending he didn’t know he was in the frame. Daniel stood behind the camera and thought, unreasonably, of that old roadside photographers used to put in malls, the kind where they give you a fake background of a mountain. He preferred the real sky.

In October, a letter arrived from a man Daniel hadn’t spoken to in years. It came on Army letterhead and said words like commendation and appreciation. He set it on the counter. Emily read it and said, “This is a big deal,” and he said, “Everything that matters is on this street.” She taped the letter next to the science fair ribbon and under the note about the keys. When he walked by that wall the next day on his way to work, he thought: this is a museum of a life that is not remarkable and yet is.

The first snow fell on a Thursday night and the world went quiet in that way that reminds people there are so few sounds we actually need. They woke to a yard that looked new. Daniel made pancakes. Emily poured syrup in a careful circle and then a design that turned into a heart. Joshua put his cheek against Max’s ribs and said, “Your fur is warm,” and Max looked at Daniel like: yes, I know.

Later, when the sun cut diamonds on the ice and the breath from their mouths hung briefly like the beginning of a story, Emily asked if they could make a list for the new year early. “I want to put ‘learn Spanish’ and ‘make a robot that can put away the dishes’ and ‘sleep through the night without waking up afraid,’” she said, and she didn’t look at him when she said the last part. He nodded and asked if they could put “fix the dryer” and “teach Max to bring my slippers” and “say Kate’s name at dinner once a week.” She said yes.

On New Year’s Eve, they stood on the porch and listened to fireworks in the distance and to someone’s muffler two streets over and to a train that announced itself with a low, dignified horn. They didn’t stay up late. They went to bed at ten because morning comes when morning comes, regardless of calendars.

When he tucked Joshua in, the boy asked, “Are we safe now?” Daniel looked at the outline of Max in the doorway and the shape of Emily in the next room, sitting cross-legged on her bed with a book open like a window. He thought of desert roads and courthouse benches and rocks wrapped in glass and bridges made of sticks. He thought of Kate and of Rachel and of sorrow that had shrunk but not disappeared and of joy that had learned to walk in its own shoes.

“We’re safer than we were,” he said, which was the truest thing he knew. “And we’re together.”

When Daniel lay down, the dog came and settled by the bed with a sigh that sounded like surrender and victory both. The house made its small noises. Somewhere far off, a train horn answered another. He closed his eyes, and for the first time in a long time, the desert stayed where it belonged and the road in his dream was not endless but led home, which, finally and at last, was not a place he returned to but a place he made and kept.