On the Wedding Night, When I Pulled Up the Blanket, the Truth Made Me Tremble: The Reason My Husband’s Family Gave Me a $2 Million Mansion Was to Marry a Poor Maid Like Me

My name is Anna Brooks, and the first time I realized a life could turn on the soft lift of a blanket was the night I married Ethan Harrison. We were strangers in silk and vows, there because his mother had pressed a neat marriage certificate on a coffee table that shone like lakewater under a noon sun. We were there because there are storms you see coming across the flats and storms that sneak up from behind your shoulder and change everything you know about yourself.

I was twenty‑six and had never owned more than what fit in a thrift‑store duffel. I grew up in a dry Texas town west of Abilene where the wind tasted like dust and copper. The year my father died in a truck accident, the grasses went brittle and rattled like bones. Mom’s lungs gave up slowly after that. Bills stacked like mail nobody wanted to claim. I left school at sixteen to clean other people’s floors in Houston. I learned how to move quietly through rooms big enough to swallow my hometown—rooms with grand pianos nobody played and marble counters that never seemed to stain.

The Harrisons lived in a gated pocket of River Oaks where the streets had names that sounded like old money and live oaks cast shade the size of small counties. They ran a real‑estate empire that built glass towers in downtown Houston and lakeside mansions in Austin, the kind of houses where time itself looked richer. Mrs. Caroline Harrison—always Caroline, never Carrie—wore pearls that seemed less an accessory than a birthright. She let me call her ma’am and asked after my mother when I brought in tea.

Their son, Ethan, was thirty‑one when I first met him. Handsome in that Houston-Old‑Guard way, a dark suit you notice after the man’s already halfway down the hall, shoulders straight, jaw calm, eyes that looked past the world like he was squinting into a far horizon. He moved with a careful grace and, sometimes, a faint, uneven hitch—as if he was gauging the ground before trusting it. He kept his distance from everyone, not out of rudeness but like a person who had learned that closeness sometimes comes with a bill.

For almost three years I cleaned their home, polished the banister that curved like a river down to a foyer of black-and-white tile, and cooked when the cook was out. I made breakfast tacos on Saturday mornings the way my dad showed me—eggs soft, tortillas warm, jalapeños diced tiny, a squeeze of lime. Ethan would pass through the kitchen on his way to somewhere else. He’d say, “Good morning, Anna,” without looking up from his phone and pocket a taco like it was contraband. It was a small thing, but small things are how poor girls clock kindness.

The morning Caroline called me into the living room, the curtains were open to a blue Houston sky that looked innocent enough to make a fool of you. She sat upright, two porcelain cups on the low table, a folder placed precisely between them. The file was thick and clean, names typed in a font you see on serious documents and fortune‑telling.

“Anna,” she said, with that precise kindness, “I’m going to be very direct.”

I stood with my hands clasped and my chin tucked like a girl in church.

She slid the folder closer. “My son needs a wife. A good wife. A steady one. I’m offering you marriage to Ethan. If you agree, the lakeside villa we built on Lake Austin—two million dollars at appraisal—will be placed in your name as a wedding gift.”

The air went thin around me. “Ma’am?”

Her eyes didn’t waver. “You would not be a servant in our home. You would be family. And independent. That’s why the title would be yours.”

I thought of my mother, of the invoices from Memorial Hermann with numbers that made my stomach flip. I thought of my rented room off Westheimer—how the window rattled when a bus passed, how the Sunday preacher down the block promised heaven and extra blessings if you gave early and often. I thought of Ethan saying good morning without looking up, and how he always took only one taco.

“I… Why me?” I asked.

“Because you are kind,” she said, as if reciting a diagnosis. “Because you do not gossip. Because you have stayed through difficult weeks without error or complaint. Because you keep your word. My son requires that.”

Requires. The word lodged somewhere between my ribs.

I should have asked other things. I should have asked everything. Instead I nodded like my body knew before my mind could catch up. “I’ll do it,” I said, and it sounded like a prayer and a sentence at once.

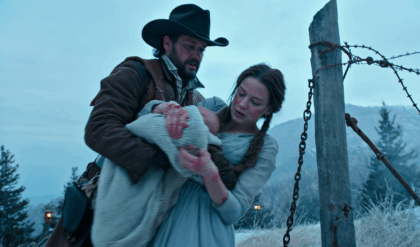

The wedding was in a downtown hotel ballroom with ceilings so high the chandeliers looked like stars scooped in handfuls. People whose pictures you see under “Society” smiled at me like I was a novelty they were politely trying not to stare at. I wore a white dress Caroline chose—the silk cool against my collarbones, the hem whispering at my ankles. Ethan stood at the end of the aisle, straight in a black tuxedo, his face thoughtful enough to look almost stern. He took my hand like it was a fragile document. When the officiant pronounced us, he leaned in, brushed his lips against my temple, and said, “Thank you,” so quietly I nearly missed it.

He didn’t look at me again until the door of the town car thumped closed and the driver slid into traffic on I‑10. City lights rose in hard angles, streets emptying toward the dark ribbon of the highway. Ethan’s jaw worked once like he was choosing a word from a difficult shelf.

“I know this is strange,” he said, still not meeting my eyes. “I’ll keep my promises.”

“What promises?” I asked.

“That the house will be in your name. That your mother’s medical bills will be covered. That you won’t be hurt.”

He said the last part like someone who had made exactly that promise before and failed it.

We drove north to Austin, up 290 past the long, flat outskirts where Buc‑ee’s signs shout like carnival barkers and then the land begins to ripple into Hill Country. The villa on Lake Austin sat above the water with a long, low grace, glass and limestone and cedar, its decks stepping down toward a private dock. The lake was inky that night, the surface broken by a breeze that pushed a cove’s worth of starlight into waves.

Inside, everything smelled new—paint and wood and twenty kinds of money. In the primary bedroom, a soft lamp burned. Ethan showed me where the extra blankets were, where the thermostat was, how the doors slid closed with a whisper you felt more than heard. He moved carefully, like a man walking among glass.

He poured water into a glass and handed it to me. “You look like you need this,” he said.

I drank and set it down, my fingers trembling against the nightstand. My skin felt too new for the room. He dimmed the light. Outside, a soft rain had begun. Austin’s kind of rain—not the mean sheets that barrel through Houston, but a hush, as if the lake itself was breathing.

I lay down on the bed, pulling the blanket up like a shield. He stayed standing a moment, looking unconvinced by the bed’s invitation. Then he eased onto the far edge, careful not to jostle the mattress. He turned on his side, away from me, leaving inches and then miles.

Something about the distance made a braver thing in me sit up. I turned and reached across that space and gently tugged the blanket higher over his shoulder—one of those little domestic gestures that says I see you even when we haven’t learned each other’s faces yet.

That’s when I felt it: a terrain under cotton where a body should be simple. Ridges where skin should be smooth, a line of healed flesh that traced from hip toward lower belly, another that crossed it. The geometry of old scars.

He flinched, just once, and swallowed. “Anna,” he said into the dark, voice a single thread, “you can sleep, okay? I won’t touch you. Not until you’re ready. Not—” He breathed. “Not until it’s right.”

I lay back down, heart pounding. I stared at the ceiling as the rain brightened and dimmed. I wasn’t a fool. I knew what a man’s body should feel like. I knew what those lines might mean. I also knew that my hands had found tenderness before they found fear. I pulled the blanket to my collarbones and told my racing mind to hush.

When I woke, pale light sifted through the curtains. On the table was a breakfast tray: a glass of warm milk, an egg sandwich wrapped in parchment, a small dish of grapefruit sprinkled with sugar like snow. Beside them, a note in careful handwriting: Went to the office. Don’t go out if it rains. —E.

I held the paper, the letters pressed deep into it. I had been crying for men since I was old enough to be lied to. This time the tears surprised me. There’s a grief to being taken care of when you’ve trained yourself to live on scraps.

We learned each other as if we were learning a city by walking it, block by block. Ethan worked three days a week teaching an art studio course at UT and the rest freelancing as a landscape painter, the kind of painter who doesn’t gild sunsets but sits still long enough to see how dusk first cools the tops of the hills and then the low grasses. Caroline came up from Houston every other weekend with casseroles you could slice clean and flowers you didn’t have to water. I planted chrysanthemums along the porch. The lake slid by like time made liquid.

Weeks later, returning from the H‑E‑B on Exposition, I heard voices through the half‑open door of the study. Caroline’s, controlled, with a thin thread of exhaustion through it; and Dr. Cole’s—Brandon Cole, Ethan’s longtime physician and friend, a compact man whose eyes missed very little.

“…surgical repair wasn’t an option back then,” Dr. Cole was saying. “We managed the pain. We kept infection at bay. He lived, Caroline. But the nerve damage—” He stopped, as if the shape of the sentence hurt to pick up.

Caroline’s reply was a whisper. “I can see he’s happier. But is she…?”

“She’s steady,” Dr. Cole said. “She doesn’t pity him. That’s important.” A pause. “How are you?”

Caroline exhaled. “My cardiologist says my heart’s like a house in July—foundation shifts when you don’t want it to. I just want to leave the right people in the right rooms.”

The right people in the right rooms. The phrasing was pure Caroline. The meaning was something warmer and heavier. I gripped the doorframe until the wood pressed crescents in my palm. I wasn’t a consolation prize. I wasn’t a footnote to someone’s legacy. But I also understood, suddenly and completely, that Ethan’s distance wasn’t pride or cruelty. It was the architecture of surviving a body that had been made to make room for pain.

That night, rain came again, this time meaner, a hill country storm that starts nice and turns nasty. Ethan went pale after dinner, a sheen of sweat on his upper lip. He gripped the counter and closed his eyes. “Sit,” I said, already reaching for my phone.

“Don’t,” he said through his teeth. “It’ll pass.”

It didn’t. He slid toward the floor and I caught his shoulder enough to slow the fall. I called 911, my voice surprisingly calm while my hands shook. In the ambulance he clutched my fingers like a drowning man grabs a rope.

“If you get tired,” he whispered, eyes unfocused, “you can leave. The house… it’s yours. Don’t let this be your sentence.”

“I’m not leaving,” I said. “You’re my husband, Ethan. This is not a bargain I made with your mother. It’s the one I made with you.”

In the ER the lights were too bright and the cold too cold and the waiting room chairs engineered to remind you how little control you have over who lives and who doesn’t. When they finally wheeled him out, braced and stable, he looked at me and tried a smile that actually reached one eye. It was the first real smile since our wedding. I felt something unclench in my chest that I didn’t know I’d been holding.

He recovered. Caroline recovered as much as a heart like that will let you. She came up to Austin with sheets of lemon squares and instructions printed in a font that brooked no argument. We sat on the back steps and watched the lake and she told me about coming up in Houston when deals were done over steak and cigarettes and how she’d learned to stand at the head of a table even when men half her age and twice her volume wanted to explain things she already owned.

“Why me?” I asked once, when the cicadas were loud and honest. “Really.”

Caroline studied me. “Because you say what you mean and you mean what you say. Because my son has been looked at his whole life—by doctors, by tabloids, by women who wanted to be seen more than they wanted to see him. Because I’m dying, Anna.”

I flinched. She smiled like a woman making peace with a truth by holding it in both hands. “The cardiologists won’t say the word, but I hear the gaps between their words. I wanted him to have someone who wasn’t impressed by the house. So I gave you the house to make sure you never had to be.”

The sentence took a long time to settle. The reason for the gift wasn’t a price tag on my dignity. It was a shield. It was leverage. In a world where money speaks louder than character, Caroline had wanted to make sure I could speak back.

Caroline’s last summer came too soon. She refused hospice at first—“Hospice is for people who have time to be delicate,” she said—but when the July heat pressed even the shade flat and her breath shortened, she agreed. In her final week, she asked to be brought up to the lake. We settled her in the bedroom that faced east, so morning hit first thing, the water going silver then gold. She asked me for tea in a porcelain cup she preferred because the rim was thin and the warmth moved to her mouth before the taste did. On her last good afternoon, she took my hand.

“Anna,” she said. “There’s a letter in my desk for you. Don’t read it until after.”

“After?”

She squeezed once and let go.

She died in the night with the kind of quiet you don’t understand unless you’ve sat with the living at the moment they’re not anymore. Ethan leaned over and pressed his forehead to hers and stayed that way until dawn decided for us that time moves whether or not we say it can.

The letter was on cream paper with her maiden monogram at the top. Caroline was the sort of woman who kept her past on good stationery. I opened it at the kitchen table, the house too still.

Anna,

If this is in your hands, I am where I’ve been headed awhile. You should know a few things clearly and in one place. The Austin property is titled in your name, free and clear. I made that choice for a reason that has nothing to do with buying you and everything to do with freeing you. This family can be generous and it can be cruel. Money in a Harrison house is both a roof and a weapon. I put the deed in your name so you could never be threatened with it.

You will hear from cousins and board members and men who think I left a soft spot to poke. Tell them this was my decision. Tell them, if needed, that the terms of the trust are met and Ethan remains controlling on the foundation’s charter. Marrying you satisfied the clause that prevented a transfer to the Caldwell cousins when he turned thirty‑two. That clause was mine. This is me keeping the right people in the right rooms.

My son needs an equal who will not borrow his dignity for herself. He needs someone whose poverty taught her to see clearly but did not teach her to stay small. I’ve watched you. You are that person.

Take care of my boy. Let him take care of you—not just with money. Neither of you were raised to receive gently. Learn that together.

—Caroline

I smoothed the page and read it again, my eyes catching on words like roof and weapon and equal. The truth slid into place. The two‑million‑dollar house wasn’t bait. It was ballast. It was Caroline’s way of making sure I could walk into any room with my back straight, even the rooms where the family pretended merit and money had been introduced earlier than they had.

The tabloids got wind of our marriage two weeks after the funeral, because that’s the kind of math grief makes possible. A headline on a site that spells “exclusive” with a dozen ads around it read: MAID TO MRS.: HOUSTON HEIR’S SECRET WEDDING—AND A $2M “GIFT.” Someone had found a blurry photo of me loading groceries into the back of Ethan’s truck and zoomed in until the pixels complained.

The first time a reporter approached me outside the flower market in Austin, he looked apologetic about it, like being rude was a job he wore reluctantly. “Mrs. Harrison,” he said, “did you marry for money?”

I wiped my hands on my apron and looked him in the eye. “No, sir,” I said. “I married a man who eats breakfast tacos one at a time and paints light like it’s a person. The house has my name on it because his mother was smarter than the world gave her credit for.”

The boardroom battle Caroline predicted arrived right on time. The Caldwell cousins—Tanner and Blake, nephews by marriage and by ambition—scheduled a “discussion” at the Harrison Foundation headquarters in downtown Houston, a building of frosted glass and steel where the elevators moved faster than the language in the minutes. They couched their issue in concern for optics and fiduciary duty. They were worried, they said, that a “domestic employee” owning a Harrison property created “confusion” among donors and partners.

I wore a navy dress that cost less than the latte Tanner spilled when he saw me. Ethan sat beside me, silent, the way a thunderhead sits when it is calculating where to let go. I placed Caroline’s letter on the table like a royal flush and slid copies across the polished wood.

“Per Caroline’s explicit instruction,” I said, summoning the part of me that learned to speak up in rooms that wanted me quiet, “the villa remains in my name. Per the trust language under Section 6.2, Ethan’s marriage before thirty‑two maintains his position as the controlling signatory on foundation charter. Caroline’s letter clarifies her intent, which aligns with the trust. Any attempt to litigate would fail, and the legal fees would be an embarrassing line item you’d have to explain to people who can read.”

Silence. Someone coughed the way people cough when they meant to laugh and thought better of it.

Tanner smiled without his eyes. “We’re all family here.”

“Indeed,” I said. “And the best families follow their matriarch’s wishes.”

We walked out into the Houston humidity that hits you like a wet towel. Ethan’s hand found mine in the parking garage. “How did you do that?” he asked softly.

“I’ve spent my whole life in rooms where I needed permission to stand,” I said. “Turns out, the deed to a house is very good posture.”

We drove back to Austin with the kind of silence that isn’t awkward, the road unspooling in front of us, the sun lowering itself into the hills. We stopped in Bastrop for barbecue and ate standing up at a high table, sauce on our wrists, as if we were just two people on our way home to nowhere anyone would ever write about.

Time did what it does—passed and left us with the proof. I opened a small flower shop off South Congress called Lakeside Blooms, where tourists bought bluebonnet bouquets in April and UT freshmen bought apology roses in September. Ethan painted in a light‑blessed corner of the living room and taught his students to look at a tree for a long time before deciding what green actually was.

One May morning, a year after Caroline died, Dr. Cole sat across from us in his office, tapping the edge of a paper against the desk. He had the look he gets when he wants to pour cold water on hope but has decided to set it in a glass with ice instead.

“There’s a surgical approach we didn’t have when you were injured,” he said to Ethan. “We’ve had success with pelvic nerve grafting in cases like yours. It’s still a gamble. It’s work. But it’s no longer science fiction.”

I reached for Ethan’s hand under the table. His fingers tightened around mine once and then let go. He stared at some point over Dr. Cole’s left shoulder like he was watching a movie only he could see. “What does success mean?” he asked.

“Pain reduction,” Dr. Cole said. “Improved function. Perhaps restored function. I’m not going to promise more than I can deliver.”

We drove home without music. A cardinal hopped along the deck rail like it was trying to find the right angle on our silence.

“Do you want to try?” I asked finally.

“I don’t know,” he said. “If I try and it fails, I lose the story I’ve made of why I am how I am. If I try and it works… I lose the story in another way. Either way, I lose something.”

I took a breath. “Maybe you trade it. Maybe you choose a different story.”

He looked at me, and there was something like fear and something like a horizon in his eyes. “If I had been like other men,” he said quietly, “would you have loved me?”

My throat went tight. “I don’t love your scars or the absence of them,” I said. “I love the man who takes one taco and leaves the other for later. I love the man who held my hand in an ambulance and told me to flee and then smiled when I told him no. I love the man who paints light like it’s a person.”

He nodded once, as if something in him had been seen and found in order.

A week later, on a Wednesday that smelled like rain without delivering it, the hospital called me from a number I recognized and did not. “Mrs. Harrison,” the nurse said. “Your husband is in pre‑op for scheduled surgery. He said you would understand.”

I drove to St. David’s like the road had been cleared just for me, my heart up in my mouth, my hands steady on the wheel because panic is a luxury poor girls don’t indulge while the job needs doing. Ethan sat in a gown, his hair mussed in that way it gets when his hands have been through it too many times. He looked up and winced.

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I knew if I told you, you’d try to carry me across the threshold of the decision. I needed to step over it myself.”

I cupped his face. “I’m here,” I said. “I’ll be here whether you walk out the same or different or not at all.”

He closed his eyes and rested his forehead against my palm. “If this works,” he murmured, “I don’t know what to do with the anger I will have to put down.”

“Maybe you stack it like firewood,” I said. “For a winter that never comes.”

The surgery took seven hours. I counted three times that many breaths. Dr. Cole came out in scrubs with that particular fatigue surgeons wear when they’ve argued with the body and won. “He’s okay,” he said. “It went as well as it could.”

Recovery was not a montage. It was slow and mean and undignified in ways that take whatever pride you had left and shake it to see what rattles. Ethan relearned how to trust muscle groups he’d filed under obsolete. He cursed a lot and then felt bad about it. I told him men had been cursing around women since men learned to speak and he could spare the apology. Some days he looked ten years younger in the morning and ten years older by dinner. Some nights he turned toward me and some nights he turned toward the window like the lake had answers. There were days he hated needing me and days he hated not needing me as much as he used to. Love is a patient animal and a feral one. It sat between us and watched.

A year after the surgery, we walked the trail by the lake without stopping for him to sit down “just to look at the view.” We stopped anyway, but because the view asked for it. A kid in a Longhorns T‑shirt zipped by on a scooter. A heron pivoted in slow motion. Ethan jogged the last twenty feet to the dock and turned back, his face open like a door. I had never seen him run.

That night he laid out a blanket on the weather‑gray boards of the dock and set a cup of chamomile tea in the center like a small moon. The lake moved around us, louder than quiet and quieter than noise.

“Do you remember,” he said, voice low, “how I said I wouldn’t touch you until you were ready?”

“I do,” I said.

“I’m ready to ask you something else,” he said. “Different question. Same promise.” He took a breath. “Will you go with me again? Into whatever this next part is? I can’t do it without the woman who taught me that staying counts as much as fixing.”

“You’ve been going with me for years,” I said, laughing through tears. “Yes.”

He pulled a drawing from his bag—a charcoal sketch of the two of us standing on the deck, our outlines simple and sure, the lake cross‑hatched into motion, the villa behind us wearing the last light. Under it he’d written: Love doesn’t need to be perfect. It only needs to stay.

Two years later, after forms and home studies and interviews that asked us to articulate what love would look like in a house on weekdays as opposed to holidays, we adopted a five‑year‑old girl from San Antonio named Lily. She had a cowlick that refused discipline and a laugh like she had more lungs than the rest of us. The day the judge in Travis County banged the gavel and said she was ours, he let her try it herself and the sound ricocheted around the courtroom like joy had been made audible.

We turned the den into her room and she covered the walls with crayon maps of everywhere we would go—Galveston for the ocean, Big Bend for the stars, Houston for the zoo and also the best kolaches. We taught her to hold a fishing pole on mornings when the fog was low and the day felt hand‑delivered. She taught us what patience looks like when it has pigtails.

On the first night she slept in the house, she kept getting up to check that we were still there. The fifth time, I lay down beside her and pulled the blanket to her chin.

“Are we staying?” she asked, blinking up at me.

“We are,” I said. “That’s the whole point.”

Word got back to us that Tanner had sold his condo and moved to Dallas to chase a venture fund and the kind of money that requires a security detail and new friends. The foundation work kept going. Ethan found himself on the porch a lot, painting the way he always had, only now he stood up sometimes and walked backward to see what the canvas had asked for. Caroline’s pearls sat in my dresser wrapped in the tissue paper she’d left them in. I wore them once a year to the foundation gala to remind the room that legacies can be stewarded by women who understand both the cost and the worth.

In April, when the bluebonnets set the medians on fire near Marble Falls, we took Lily to see them. She lay in the flowers and stretched her arms like she was making a snow angel of spring. People pulled over and did the same. For a long minute, the highway forgot itself.

Sometimes visitors—old acquaintances of Caroline’s or donors who wanted to confirm we were not a myth—would stand on the deck and look at the water and the house and then at me and say, more or less, “It must be nice.” It was. Not because of the square footage or the appraisal or the kind of oven that preheats before you finish turning the dial, but because the house had kept its promise. It had made me independent enough to say yes to love for no other reason than love.

On the tenth anniversary of our wedding, we went back to Houston for dinner at a small restaurant off Montrose that serves deviled eggs so good they’ll silence a table. On the way out, as the heat hugged us like a relative, I caught our reflection in the window—Ethan taller by a head and a half, me at his side, our daughter between us, one of his hands on my shoulder and one of mine on Lily’s braid. We looked, for the first time in my life, like a family that didn’t feel borrowed.

Back at the lake that night, after Lily fell asleep, we went out to the dock. The breeze was soft and the bats were making their rounds like tiny, efficient shadows. I pulled the blanket over our laps and leaned into his shoulder.

“Do you ever think about that first night?” he asked.

“Every time I change the sheets,” I said, and he laughed, startled and genuine.

“I was afraid,” he said. “I thought the truth of me would make you recoil.”

“I trembled,” I said. “But not because I was scared of you. Because I realized love might ask more of me than I’d planned on giving. And I wanted to give it anyway.”

He turned and kissed my temple the way he had in the hotel ballroom before we knew how to look at each other. The lake carried on like time made liquid. Somewhere a neighbor’s wind chime made a sound so light it felt like a secret passed in daylight.

If anyone ever asks me why a family as wealthy as the Harrisons gave a poor maid a two‑million‑dollar mansion, I tell them this: Because Caroline Harrison had lived long enough to know how people use roofs as leverage. She wanted me to have a home nobody could take back, so when I chose her son, everyone would understand I chose him. Not his house. Not his name. Him.

And when I pulled the blanket up on our wedding night and felt the truth written across his body, I understood the gift for what it was—not a purchase, not a payment, but a way to begin as equals. A way to stay. A way to say, even in rooms where money is law, that love can build a house of its own and it’ll stand just fine against the wind.