The night was warm in Los Angeles, and the pool at the Langston estate glittered beneath strings of fairy lights that trembled in the faint breath of a hillside breeze. A jazz quartet skimmed notes across the water. Laughter dripped like honey from marble steps. Jewel-toned gowns caught camera flashes and tossed them back at the century-old sycamores that stood guard at the edge of the property as if they’d seen everything human beings could do to each other and still kept their leaves.

Claire Mitchell held her tray in both hands, fingers stinging where condensation had slicked the metal. She was twenty-two and too tired to be twenty-two, the kind of tired that sits behind your eyes and makes every step a calculation. Twelve hours at the diner, four hours on this catering shift, a bus ride home to a studio in Van Nuys where the box fan rattled and the rent devoured half her pay, and somewhere in that math there was her mother, Evelyn, whose breath hiccuped when the night got cold. Medication helped. Insurance didn’t. Numbers never worked the way stories promised; you had to muscle them into place.

From the moment Claire stepped onto the flagstones, she was invisible. That used to bother her. Lately, it was a relief. Invisible meant nobody asked questions that required the truth. Invisible meant nobody noticed if your shoes were a half-size too big because the store had been out of your size. Invisible meant you could watch and learn and collect tiny maps of how power walked through the world.

She learned that evening that power laughed without looking first.

Claire edged past a ring of women in sequins, the kind of sequins that turned every move into a small electric storm. One of them pivoted with a smile too white to be real and caught the lip of Claire’s tray with an elbow. Champagne glasses hiccuped and clinked. Claire saved them all. She smiled with her eyes the way Tasha—shift lead and saint—had taught her. The woman didn’t notice. Or if she did, her attention wasn’t interested in mercy.

“Watch where you’re going, servant,” someone sang over a flute of rosé.

Madison Langston glowed like the party was hers to inhale. She had the kind of face that knew it would be photographed. She had the kind of friends who watched her mouth so they could laugh a half-second after it moved. She had a satin dress in a color that could stop traffic, and she tilted her head in a way that said the world should tilt with it.

Claire kept moving. “Sorry,” she murmured, though the apology wasn’t for Madison. It was for the tray. It was for Tasha, who had begged the crew to be perfect tonight because the client was “particular” and “repeat business” and “we need this.”

By the pool’s edge, a banker type gestured for a refill without looking away from his own reflection in the water. Claire poured. She recalculated her route—half step left, quarter turn, shoulder to shoulder with the current of jewel colors drifting toward the dessert bar. She could feel the smile, could feel it like a mask gently attached with two pins, one at each cheek. She could keep it on forever if she had to.

She didn’t see Madison approach. She felt the air change. Heard a half-giggle, like the compressed sound of a balloon between fingers. The shove came light and quick, the kind of touch you’d use to move a door aside where a person ought to be.

Time split. The tray lifted from her hands like it knew a better life awaited it. Glass went airborne in a constellation she would see again behind her eyelids for months. Cold hit her like an answer nobody asked for. The water swallowed sound. When she came up, mascara carved warm roads down her cheeks and her hair stuck to her head like a confession.

The party roared. Phones rose. Somebody yelled, “That’s the entertainment!” and an eddy of laughter pulled the remark away. Claire found the lip of the pool with her palms and pressed. Her shoes were slick bricks. She slid, knee barking the tile, a sting that would find a purple bloom tomorrow if tomorrow included a moment for looking.

A small, shaking part of her considered vanishing. Walk off the job, take the bus as she was, soaked and shivering, let the night have the money. But another part—the part that counted pills into a day-of-the-week organizer and learned which grocery stores set out the good bruised bananas on Tuesdays—refused to be poor and humiliated. If she had to choose, she could only afford one.

She got herself out. She stood with the water running off her uniform in quiet sheets. She pressed her hands flat against her sides so she wouldn’t wring the hem like a child. She lifted her chin just enough to keep tears from tipping.

That was when the music thinned to a wire and a voice—low, steady—cut the laugh track. “What the hell is going on here?”

Daniel Hayes did not arrive so much as appear, the way certain kinds of gravity make themselves known without force. He moved like someone who had learned to fit his shoulders through doorways narrower than his ambition and had never quite unlearned it. The tuxedo looked expensive on him, but not like a costume. He carried a tiredness that had been earned the long way.

“Who did this?” he asked, and a bubble of silence formed around his words, pushing the party outward. Nobody spoke. Then Madison drifted forward in a cloud of perfume and performance. Her smile had an alibi built in.

“It was a joke,” she said, light as foam. “She slipped.”

Daniel’s eyes—gray like smoke stretching thin at dawn—did not leave Claire. Then they went to Madison and did not blink. “A joke is forgetting the punchline. A joke is telling it badly. What you did is bullying.”

The word landed. It always does, even when nobody wants to be the kind of person who recognizes it. Someone coughed. Someone else found sudden interest in a garnish.

Madison’s laugh curdled. “She’s just staff.”

The smallest wince crossed Daniel’s mouth, like a memory had stepped on a nail. “There is no ‘just’ in front of a human being,” he said. He shrugged off his jacket and walked to Claire. The heat of it startled her when he settled it over her shoulders, the same way kindness always startles when you expect the opposite. “Are you hurt?” he asked, quieter now.

“I’m fine,” Claire said, and surprised herself by almost believing it because he sounded like someone who would believe her.

“Good,” he said. “Then I’m going to be un-fine on your behalf for a minute.” He turned back to the party with an ease that suggested he had done harder things than confront a roomful of money. “If you ever want to know what kind of person you are,” he told them, “watch yourself around people who can’t do anything for you.”

Richard Langston—host, real estate patriarch, a jawline paid for in gym hours—made his move then, threading through guests with the smile of a man who had learned to smother fires with charm. “Daniel,” he said, hand extended. “I think there’s been a misunderstanding. It’s a party. Things happen.”

“Things don’t just happen, Richard,” Daniel said, not taking the hand. “People happen. Choices happen.”

Behind Richard, Madison’s mouth flattened the way privilege flattens when it collides with an object it didn’t expect to be there. She rolled her eyes toward the house, as if better company resided inside walls, as if dignity were just a service they’d forgotten to tip for.

Tasha reached Claire’s side with a towel that had lost most of its warmth to the night. “You don’t have to stay,” she whispered. “I’ll mark you paid.”

Claire’s throat hurt with the effort it took to nod. “Thanks,” she managed.

Daniel watched the exchange, then to Richard: “Your guests laughed at someone doing her job. I’ll remember that next time you ask me to walk your investors through a build-out.”

Several heads swiveled. In certain climates, money is the only weather report anyone cares to check.

Richard’s smile held. “Let me speak with my daughter.”

“You do that,” Daniel said, and the old trees along the fence line seemed to lean a fraction closer, as if even they wanted to hear what accountability sounds like.

He walked Claire away from the pool, from the phones that tried to drink her. At a quiet corner of the yard near a stone bench, he crouched a little to be at her level and asked again, “You sure you’re okay?”

She nodded. Shame throttled the room where words usually stayed. Then a few made it out. “Thank you,” she said. “You didn’t have to.”

“Somebody did,” he said simply. “I’m glad it was me.”

He flagged the catering manager—mustache trembling like it wanted to apologize before its owner did. “She gets paid in full,” Daniel said, “and she goes home now.” There was a tone he used for certain sentences, a register that made disagreement look like poor form.

On her way out, Claire caught one last sight of the pool. Its surface had smoothed over as if nothing ugly had ever broken it. She held Daniel’s jacket closed with one hand, the other cupped around the memory of the tray flyspecked with stars.

He walked her to the driveway where a black sedan waited, sleek as a thought you can’t shake. “I’ll get you home,” he said. “No argument.”

In the car, the city unscrolled—switchback streets pouring down from the hills, the red pulse of brake lights on the 405 like a vein under skin. Daniel didn’t fill the air with questions. When she finally spoke, he listened with his whole face. She told him about the twelve-hour shifts that stacked like boxes. She told him about Evelyn’s oxygen machine and the way their apartment windows floated back the noise from the alley like a broken radio. She told him about community college brochures she kept in a drawer like postcards from a country she couldn’t afford to visit.

“I want to be a nurse,” she said, the words almost embarrassing because they felt fragile when said out loud.

“Of course you do,” he said. He said it the way you say of course when a person tells you they want to breathe. “You’ve got the gear for it.”

“What gear?” she asked, wary of being flattered.

“Steady hands,” he said. “High threshold for nonsense. The ability to make a room forget itself.” He smiled brief as a match. “Call me tomorrow.” He handed her a card—white, heavy, the letters deep enough to run a fingertip along. “If you want a better job while you get to the job you want, I’ve got one. No strings, no savior complex. Admin at my foundation. Decent pay. Real hours.”

“Why me?” The doubt was just honest.

“Because somebody reached back for me once,” he said. “Turns out you can build a life out of those moments.”

He dropped her at the curb. The building wore its 1970s sadness without apology. A neighbor’s television leaked laughter. Claire stood there a second longer than she needed to, the jacket warm on her shoulders, the card cool in her pocket. She looked up. A rectangle of light in her window was Evelyn’s world tonight.

Inside, the apartment smelled faintly of chicken soup and the lemon cleaner Claire used in amounts that made the label unnecessary. Evelyn sat on the couch beneath an afghan Claire remembered from every sick day of second grade. Two oxygen tanks leaned against the wall like quiet bodyguards.

“You’re late,” Evelyn said, but the words were wrapped in that worried humor older mothers keep for daughters who come home past midnight.

“I fell in a pool,” Claire said, and for the first time since the water she laughed a little at the absurdity of saying it.

Evelyn’s eyes sharpened the way hawks do when a mouse makes a sound far away. “What?”

“It’s fine.” Claire knelt, undoing shoes that squelched. “It was a whole scene. A man—Daniel Hayes—gave me his jacket. I’ll wash it tomorrow.” She didn’t realize she was crying until the words blurred. “He stuck up for me, Mom.”

Evelyn’s hand found her scalp, the old comfort that still worked. “Good,” she whispered, and her voice had iron Claire had never had to manufacture herself. “Good. People forget, but there are still men like that.”

Claire slept like a person pulled up out of something that had wanted to keep her.

She called the next afternoon. The receptionist at Hayes Properties and Philanthropy sounded exactly like somebody who could run a city if asked. “He’s expecting your call,” the woman said. There are sentences that want to turn your knees to water. This was one.

Daniel’s office looked out over the part of downtown that had tried to get respectable and almost had. Concrete skeletons were being filled in with glass. Cranes held their breath. Inside, the floors were more oak than you could afford to look at for long, and the art on the walls was new in a way that meant someone young had convinced someone rich to take a chance.

He came around the desk instead of calling her to it. “Claire,” he said as if they were old acquaintances at a grocery store in a smaller life. “Thanks for coming.”

“I wasn’t sure I would.” That was the most honest sentence she had said in days.

“Me neither, twenty-two-year-old me would’ve told forty-five-year-old me to get lost.” He shrugged. “Here’s the offer. Part-time or full-time admin for the Hayes Foundation—phone work, event logistics, vendor wrangling, the kind of stuff invisible people do so visible people think evenings go smoothly under fairy lights. Health insurance after ninety days. Tuition support if you enroll in prerequisites at LACC or Pierce. You don’t owe me anything. You owe yourself something.”

“Why are you doing this?” Her voice was smaller than she wanted it to be.

“I grew up in a double-wide outside Bakersfield,” he said, like he was handing her the only proof she would ever need. “My mom cleaned motels off Route 58. I swung a hammer until my shoulders forgot how to sleep. A foreman once pushed me off scaffolding, called it a joke. The crew laughed. A site manager dragged me to the clinic, paid the bill, told me I wasn’t crazy. People remember the ones who pay the bill.”

She took the job. She told herself it was temporary, a stepping stone, a then I’ll figure it out. That’s how people like her had to make plans—like hopscotch patterns you drew in chalk and prayed wouldn’t wash away before you got to the last square.

The first week, she learned the phone system the way a musician learns scales—finger by finger until the sound became something like competence. She learned Daniel took his coffee black and his mornings uninterruptible. She learned the rhythm of a man who built things in his head before he allowed them to exist in the world.

The second week, the internet did what it does. Someone’s video of the pool incident found a vein. It circulated with captions that punished and defended everyone at once. COMMENTS DISABLED lived beneath news segments when the segments figured out rage wasn’t a renewable resource.

Claire turned her phone facedown at her desk. She stuck to the tasks. She built a spreadsheet for grant cycles that had previously lived in three brains and two notebooks. She said please and thank you to vendors who were shocked by the novelty of hearing both from someone with a Hayes email address.

On a Tuesday, the receptionist—Mara, who’d been running the place ten years and always told the truth even when it ordered the room to rearrange itself—leaned on Claire’s desk. “PR wants to know if you’ll speak. Not long. A statement. You don’t owe them, or us, or anyone.”

Claire pictured her mother’s face when strangers online called her names. She pictured Madison’s hand mid-shove. “What would I even say?”

“That it hurt,” Mara said. “That you’re not a symbol. That you’re a person who went to work and got wet.”

They wrote it together in the little kitchen where nonprofits stored their hope between granola bars and microwave hummus. Claire read it once into a camera that blinked the way nerves do.

“I’m a worker,” she said. “I’m also a daughter and a future nurse and a person in this city. I went to do my job and someone decided to make a story out of me without my permission. I’d like to take my story back. Here it is: I’ve got rent due. I’ve got a mom whose lungs behave when the air does. I’ve got morning classes starting at LACC in the fall, and I’m going to finish what I start.”

Maybe it was because she didn’t ask anyone to cancel anyone. Maybe it was because she made it small enough to hold. The thing didn’t explode. It just moved. People wrote in saying they had been the one who got pushed, the one who laughed, the one who stood there and wished they had said something. The flood never reached her apartment door. It felt almost like a tide that rose and receded without dragging her chairs into the street.

Madison wrote an apology on a notes app and put it online. It had all the right words, arranged as if for display. Claire read it, felt nothing, and went back to entering receipts.

Classes started. Biology felt like an answer sheet written on the body. Anatomy was a map that made everything she had felt while holding her mother’s hand make sense in new, gentler ways. At the back of the community college auditorium, a Dodger cap hid a head that could recite every cranial nerve in order and had already named two after actors. “I’m Jay,” he said. “If you want a study partner who makes terrible flashcards but brings snacks.”

She did. They met in the library where the air conditioning pretended LA wasn’t a town built on sun-baked optimism. They quizzed each other until the Part of Her That Panicked at Tests realized they were just questions dressed like monsters.

Meanwhile, the foundation’s fall gala inched closer. It would raise money for a program Daniel had dreamed up that summer and called Dignity First—a training pipeline for hospitality and service workers that taught not just plate-carrying and wine-pouring but also how to navigate people’s worst selves without absorbing them. He wanted stipends, childcare, placement guarantees, a small thing large enough to change a street’s worth of lives over time.

“Where do you want the gala?” Mara asked in a planning meeting where post-its bloomed on the wall like migrating birds.

“Anywhere but a place with a pool,” Daniel said dryly, and the room laughed in a way that felt like group therapy. Then he added, “Actually, scratch that. Book the Langston.”

Heads snapped. Even his.

“You serious?” Mara asked, pen paused.

“Richard wants back in my orbit,” Daniel said. “He’s sent three golf invitations and a case of wine my neighbor’s probably enjoying. He’ll rent us the place. He’ll get to make a donation that looks like grace. We’ll get to build something bigger out of something small and mean.” He looked at Claire. “But not if you don’t want it.”

It is a specific kind of power to be asked instead of told, and it is hard for people who haven’t had much of it to hold it without shaking. Claire swallowed. “Do it,” she said. “Let’s put something better there.”

They planned the logistics as if planning could protect everyone from weather and behavior. Security would be visible and bored-looking. The pool would be covered by a clear platform strong enough for a marching band. Staff spaces would be clearly marked as off-limits to anyone whose shoes cost more than some people’s cars.

On a Thursday afternoon, Madison arrived at the Hayes office without an appointment and with sunglasses that could have shielded a national park. Mara called Claire. “It’s up to you,” she said. “I can tell her to leave.”

“Send her in,” Claire said, because she had learned that sometimes the worst thing that can happen is you have to endure the thing you’ve already endured.

Madison perched on the edge of a chair like it might retaliate. She removed the sunglasses the way magicians remove tablecloths—quickly, with assurance that nothing beneath will spill. Her eyes were tired in a human way that didn’t match the persona Claire recognized from glossy feeds.

“I’m here to apologize,” Madison said. The notes-app speech was probably in her pocket again. She didn’t reach for it. “Not on the internet. Here. To you.”

Claire waited. Silence can be a kind of honesty too.

“My dad said hosting your gala was good PR,” Madison went on. “And he’s right. But I also want the embarrassment to stop living in my chest like a small animal. I don’t know how to do that except to tell you I’m sorry to your face. I was drunk. I was cruel. I thought being funny would make people look at me in a way that felt like love.” She exhaled, a sound that fogged her own reflection in the office window. “You don’t owe me forgiveness. I’m just… trying not to be the person who would do that again.”

Claire felt the room widen, the way rooms do when people finally tell the exact truth. “Thank you for saying it,” she said. “I accept the apology. That doesn’t undo it.”

“I know,” Madison said quickly. “If you want me out of sight at the gala—”

“I want you to work,” Claire said, surprising herself. “You’re going to train with our staff for a week. You’re going to run plates, refill coffee, buss tables, memorize the floor plan, know where the burn cream is. You want that animal out of your chest? Give it a job.”

Madison blinked. “Okay,” she said after a beat. “Okay.”

The week before the gala, Madison showed up in black slacks and flat shoes, hair pinned back in the functional way the job requires. She learned to carry a tray with a hand that didn’t wobble. She learned to anticipate the reach of strangers. She learned to say Ma’am and Sir without letting them hollow her out. When she cut her finger on an oyster shell, she didn’t cry. She washed the cut, bandaged it under Tasha’s supervision, and polished twelve dozen glasses as if the water in them might someday reflect something she could like about herself.

“Not bad,” Tasha told her grudgingly at the end of a shift. “Don’t make me regret saying that.”

“I won’t,” Madison said, and sounded like a person who had just discovered that there are better drugs than attention.

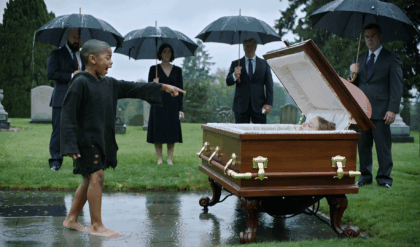

The night of the gala, the Langston estate looked like someone had forgiven it. The clear platform over the pool made the water an ornament instead of a trap, and the lights above found their own faces there and smiled back. Servers—paid well, briefed thoroughly—moved like a school of fish that had a destination in mind. Daniel wore a suit the color of storms at a distance. Claire wore a black dress that didn’t apologize for being simple.

At seven twenty-three, a woman at table eight—late fifties, diamonds like a constellation, posture like a ruler—collapsed forward into her soup.

The first sound was her husband’s wordless Oh. The second was the almost-music of chairs being shoved back at once. Claire was moving before she knew she was moving, the way a body names what it is when called. “Call 911,” she said to no one and everyone. “Tell them possible cardiac. Table eight, Langston estate, access through the west gate.”

She reached the woman—later she would learn the name: Diana Hargrove, beneficiary of an oil fortune she believed had insulated her from biology. “Mrs. Hargrove,” Claire said, even though the woman couldn’t answer, because names bring people back to rooms faster than anything. She checked for pulse, breath. There was one and then not. “I’m starting compressions,” she told the husband because people like to be told. “Sir, I need you to move.”

He moved.

Claire’s shoulders found a rhythm they had practiced on a dummy that smelled like disinfectant and old panic. Thirty compressions, two breaths with a mask someone shoved into her hand because Mara had insisted on the kit and Tasha had insisted on stationing it fifteen feet from anywhere that mattered. Someone—Madison, it turned out—counted out loud because counting is a spell.

“EMS is two minutes out,” Daniel said, voice steady, a metronome in a room that had tipped sideways.

“Stay with me,” Claire said to the woman and to herself and to the part of the night that always wants to become a different story.

A cough. A sound. A body being dragged back to shore. When the EMTs arrived, the woman had a pulse that didn’t look like drowning anymore. They took her and the night took a breath and the room learned to resume being a room without pretending nothing had happened.

Later, in the kitchen where joy and disaster both get plated, Madison sat on a crate, trembling with adrenaline. “You didn’t even think,” she said to Claire, admiration and awe making a blank page of her face.

“I had to think,” Claire said. “I had to decide not to be scared for ten seconds at a time.”

“You saved her.” The words had that new weight when a person has said too many empty ones.

“I was there,” Claire said. “That’s all any of us can do. Be there.” She surprised herself by reaching for Madison’s hand. “You did good. Counting matters. People come back to counts. Ask any paramedic.”

The gala raised more than the goal. It raised something else too—permission for the night to be remembered for the right part. Daniel’s speech was shorter than planned and better. He told the story of a man pushed off scaffolding. He told the story of a pool and the moment a jacket becomes a bridge. He asked for money and he asked for something you can’t write a check for. “If you want to build a city,” he said, “put your hands where your mouth is. If you want to build a life, put your feet where your principles are.”

Two weeks later, a thank-you card arrived at the foundation on thick paper with flecks in it that probably had a name. Inside, a hand that had wobbled over a hospital clipboard wrote, You held my life in your hands. When you’re ready, I’d like to give your program whatever it needs to grow. It was signed, simply, Diana.

By winter, Dignity First had classrooms in a repurposed carwash on Victory Boulevard. The smell of soap never left the walls, and that turned out to be a kind of blessing. People came in on buses and left with schedules and confidence and a small white card with their name spelled right on the first try. Industry partners called Mara and asked if they could “get in on the pipeline,” like decency were a ride you could buy a ticket for.

Claire worked her desk and her classes and her life. She mastered dosage math. She learned that some patients will laugh at you and then weep and then thank you and none of those are about you. On Saturdays, she and Jay tutored high school seniors who had decided to do something unforgivable: go further than the map their neighborhood drew for them. They ate burritos, because burritos are a love language.

If you’re looking for a moment where Claire and Daniel admitted it was love, there isn’t one. There are instead a hundred small moments that added up the way compound interest does when you thought you had nothing in the account. Daniel drove Evelyn to a pulmonology appointment when Claire’s bus didn’t come. Claire told Daniel he had spinach in his teeth before a board meeting. He laughed with his whole chest in the way men do only when they’re not in charge. She fixed the mic on his lapel before he walked onstage and he didn’t make a joke of it because he understood that letting someone help you is the other half of helping.

On a March afternoon, a man from Daniel’s board stopped by the foundation. He had a tan sweater over a collared shirt and the kind of hair that makes a barber proud of an education. “Daniel,” he said later in Daniel’s office, “some of the partners are nervous. The Dignity program, the… noise. Investors like dinners, not… movements.”

“What they like,” Daniel said, “doesn’t enter into the definition of what I can live with.”

“Just watch your back,” the man said, which is what people say when they want you to thank them for the knife already positioned.

That night, Daniel sat in the tiny kitchen of Claire’s apartment because Evelyn had insisted on cooking for him as payment for too much kindness. He ate chicken pot pie that tasted like the feeling of being told you don’t have to perform to be invited. “They might try to push me out of my own company,” he said. He tried to sound like a man who found that possibility interesting in a theoretical way.

Claire leaned against the counter, a spoon in her hand like a baton. “Let them try,” she said. “You can build things they can’t imagine. You built me a bridge out of a night I thought might end me.”

He met her eyes, and it wasn’t romantic exactly. It was a recognition ceremony. “Deal,” he said.

They planned. They moved assets like chess pieces, the way you do when you know the other side has always assumed you don’t know the rules. Daniel created a separate LLC for the foundation’s property, quietly and legally, the way people who grew up poor learn to be loud only when the law asks them to be. He groomed a lieutenant at Hayes Properties who understood the difference between extravagance and excellence. “If they want the keys to the car,” he told him, “they’re going to discover I’ve already bought a better car.”

By summer, the board did what boards do when their reflections in pool water are disturbed. They suggested a leadership transition “for optics.” Daniel stepped down from the CEO role with a smile that made the news believe it had witnessed a coronation instead of a refusal. He retained controlling interest in the projects that made the state better instead of richer. He moved his desk to the foundation full-time and felt a muscle unclench he didn’t know he had. The city noticed without making a speech of it.

On the one-year anniversary of the gala, the Langston estate hosted a graduation for the first Dignity First cohort. People wore their best shoes. Their children sat in folding chairs and clapped with popcorn hands. Madison handed out certificates with a grace that came from practice and humiliation and choosing better on purpose.

Richard hovered at the edges like a man who wanted credit for a weather pattern. He made a grand donation onstage and mispronounced the program’s name by accident, then corrected himself because he had learned the hard way you can’t throw money at people and call it intimacy.

After the ceremony, Diana Hargrove found Claire near the roses. “You never came by for that lunch I promised,” Diana said. “I’ve been doing cardiac rehab. My trainer is thirty and looks like a boy band, and I keep asking him if he’s old enough to have seen a landline.” Her laugh had earned its way back. “I mean it, dear. The fund is set up. Use it. Grow your program. Put my name on a plaque small enough you have to bend to read it, so even the rich have to bow to get what they want.”

“Deal,” Claire said, because she had learned that word from a man who only used it when he meant it.

Life didn’t become a movie after that. It became a life. Evelyn had good months and hard ones. Bills still arrived like postcards from places you never wanted to visit. The bus still didn’t come some days because LA is a place built for cars and patience. Some donors made faces when they learned stipends included childcare because people love to support the idea of a worker until the worker looks like a mother. But the program graduated its second class. Claire passed Pharmacology with an A minus that felt like a trophy.

One evening, as twilight painted the city in that specific color LA invented for itself—somewhere between peach and forgiveness—Claire and Daniel stood outside the carwash-turned-campus. The Dignity First sign hummed softly. Inside, Madison was leading a workshop on microaggressions for new trainees and saying the word out loud without flinching.

“You’re doing it,” Daniel said softly. “You wanted to be a nurse. You’re almost there.”

“I wanted to be a nurse,” Claire said. “I still do. But I also want to be the person who makes the room safer for the next me.”

Daniel nodded. “We contain multitudes, Miss Mitchell.”

She looked at him and saw a man who had refused to harden where most men would have calcified. She reached out, took his hand. The gesture surprised both of them with how unsurprising it felt. When he leaned to kiss her, it was brief and certain and conducted like a business transaction in a language only the two of them spoke. She laughed, and he laughed, and it felt like two gears finally acknowledging the teeth between them were meant to meet.

They didn’t announce anything. They didn’t not. People can be happy without putting a ribbon around it for others to open.

The second year’s gala was at a union hall in Boyle Heights with a view of a freeway and a mural of Our Lady of Guadalupe that watched over the parking lot like a patient aunt. The food was better than at any mansion, because it was cooked by women who had made arroz con pollo for people they loved more than they loved applause. The mayor said words into a microphone that sounded almost like gratitude in a man who had been elected twice.

When Daniel spoke, he told a story he hadn’t told before. “The first time I ever saw someone throw a tray at a worker,” he said, “I was sixteen. It was a diner off Highway 99. The man did it because his eggs were over instead of easy. I watched a busboy mop up yolk and shame. I didn’t say anything. I thought about that boy for a month. I swore if I ever had money or power, I would never let a room forget itself like that again.” He let the silence fill in the edges of what didn’t need to be explained. “It took me a while to keep that promise. Then one summer night, I got the chance.”

He looked at Claire without looking at her, the way people in love are careful not to use a room the way teenagers use a mirror.

After the applause, Richard Langston came up as if drawn by the magnetic field around relevance. “Daniel,” he said, “we should talk about the Santa Monica project.”

“We’re full up this year,” Daniel said pleasantly. “But send your folks by the training center. If you’re going to open anything in my city, your staff is going to know how to be the kind of people rooms remember for the right reasons.”

Richard’s smile thinned like it had been rolled out too often. “Of course.” He looked at Claire as if seeing her for the first time as anything other than a utility or a threat. “You did well here.”

“She did,” Daniel said, and if protection could be a tone, it would have been that.

In the middle of August, a heat wave pressed its thumb on the Valley. Evelyn had a scare and a hospital stay. Claire slept in a chair with her head against a window that looked out over the loading dock where trucks brought in supplies that kept people alive in ways that were too boring to be in a movie. When the discharge papers were signed, Evelyn made a joke about ordering a cheeseburger on the way home because hospital Jell-O had convinced her she had been too virtuous. “Get two,” Claire said, and they did, and they ate them in the car with the AC on and the radio playing a song that had charted before Claire was born.

At semester’s end, Claire walked across a stage at LACC in a cheap robe that still felt like silk because of what it meant. Evelyn cried. Daniel stood at the back because he knew what his face would look like if he tried not to. Jay whooped. Tasha held a bouquet of grocery store flowers like she was guarding state secrets.

Later that night, they went to the diner where Claire had her first job and the waitress who now ran the place comped their pie. “To nurses,” she said, raising her coffee mug like a crystal flute.

“Almost nurse,” Claire corrected. “RN in a year if the universe behaves.”

“The universe doesn’t behave,” the woman said. “But you will. That’s the trick.”

On a Tuesday in November, Claire’s phone buzzed with a text from a number she didn’t know. It was a video from a security camera at a different kind of party in a different hilltop house. A server tripped. A young man—expensive watch, cheap soul—laughed and made a pushing gesture as if teaching the room a dance. Before anyone could join in, a woman crossed the frame and put a hand on the server’s elbow, steady and unshowy. She righted the tray. She said something that made the room recalibrate. The text read: Madison. Thought you should see.

Claire watched it twice. She smiled because redemption isn’t a parade, it’s a series of parking tickets quietly paid on time. She sent no reply because sometimes the best answer is to keep building the thing you said you would build.

Years have a way of arranging themselves into stories whether you give them permission or not. Claire finished her program and pinned her badge on with hands that shook the way hands shake when they remember other nights. She took a job at County because that’s where the people who needed her would never be able to pay her back with anything but their lives. She worked nights and loved them in the way nurses love what breaks them because it leaves a better shape behind.

Dignity First opened an outpost in Long Beach, then Santa Ana. A national chain offered to buy the curriculum. They said no, then yes, then no again when the chain wanted to add a clause about image rights. The program didn’t belong to anyone who thought they could turn it into a commercial. It belonged to the city and to people who set out forks in the right order and knew which questions matter when the room goes sideways.

On a spring evening thick with jacaranda petals and car alarms, Claire and Daniel stood in line at a taco truck near MacArthur Park, their shoulders touching the way seasons do when they’re not fighting for the calendar. “Do you ever think about that night?” Daniel asked, and he didn’t need to be more specific.

“I think about all the nights before it,” Claire said. “How many quiet humiliations it takes to make a person good at pretending they weren’t just humiliated. I think about what it meant that you didn’t pretend you didn’t see it.” She looked up at him and found his mouth shaped like a Yes he hadn’t said yet. “I think about how easy it would’ve been for both of us to walk away.”

“We didn’t,” he said softly.

“We didn’t,” she echoed.

They took their tacos to a plastic table under a streetlight that hummed like it had something it wanted to confess. A kid nearby did wheelies on a bike too big for him. Someone’s radio played a love song in a language Claire didn’t speak but understood anyway because love songs always translate themselves if you let them.

Across the street, a woman in a server’s uniform waited for the bus, spine straight, eyes scanning for a thing that kept not arriving. Claire watched her and felt the old ache and the new pride braided together in a rope strong enough to pull something. She stood, walked across, and handed the woman a card that said Dignity First on one side and Claire Mitchell, RN on the other.

“It’s not charity,” Claire said when the woman hesitated. “It’s an option. If you want it, there’s a class starting Monday. If you don’t, there will be another. We’ll still be here.”

The woman read the card like it might change shape in her fingers. “Thank you,” she said. “People don’t usually see us.”

“I used to be you,” Claire said. “I never stopped being you.”

Back at the table, Daniel watched her with that expression he wore when a blueprint in his head matched a building in the world. He reached for her hand again and found it. The city breathed around them like a giant animal settling into sleep.

And somewhere, a pool at the top of a hill lay still and blank, a mirror that had once carried a memory it didn’t deserve. The trees above it kept their leaves. The parties kept their music. But the rooms learned, a little, to recognize themselves. Not because a millionaire walked in and made a speech, though that had its place, but because a woman walked out of a pool, dried off, went to work, and built a door where there had been a wall.

The laughter that had once cut her now lived in a different register in Claire’s memory, softer, like a warning on a weather report for a storm that might come back but would never again catch the city unroofed. People still did what people do. But now there were others who did what people could do. They stepped forward. They said the names. They counted. Thirty compressions, two breaths, again and again, until the heart of a room started beating in rhythm with decency, and stayed.