The boy insisted that his father dig his mother’s grave, and the moment the coffin lid was opened left everyone breathless.

“Dad, you have to open Mom’s coffin. Please. Something isn’t right.”

Twelve-year-old Ethan Miller stood trembling in the living room of their modest ranch in Worthington, Ohio, knuckles white against the seams of his jeans, voice shaking but stubborn as oak. Daniel Miller—forty-two, construction foreman, hands like split pine, eyes rubbed raw from weeks of lost sleep—could not bear the words. Grief had turned his chest into a cupboard full of rattling jars; every step set something breaking loose. Sarah had been gone six weeks, taken by what the doctors called cardiac arrest. The funeral had been quick because everything felt quick when your heart was a runaway train.

“Ethan, enough,” Daniel said, rubbing the pads of his fingers against his temples. “Your mom’s gone. Let her rest.”

But the boy didn’t move. He stared at the calendar on the kitchen wall—the one with the Buckeyes schedule and a photograph of a barn in winter—and then back at his father. “Dad, I saw her hand move. In the coffin. Before they closed it.”

The words moved through the room like cold air, snuffing out the soft lamplight. Daniel felt the floor tilt. There had been a tug at his sleeve at the graveside, a small desperate pull he’d shaken off because grief made you cruel, because the world muffled itself and you learned to breathe through cotton. He had chosen, then, to trust the people in white coats who said what they said with quiet certainty.

“You were scared,” Daniel said, hearing the apology in his own voice. “We both were.”

“I know what I saw.” Ethan’s lashes glistened. “Please.”

In the end it wasn’t logic that broke Daniel’s resistance; it was the sound of Ethan’s voice. That quaver lived in the shared Dobell’s Hardware tape measure of their home, in the identical left-handed cowlick that always refused a comb, in the bucket of baseballs in the garage labeled “Dad & E.” He made the appointment at the county office because he had to sleep again. He completed an affidavit because he couldn’t keep walking past Sarah’s coffee mug—the chipped blue one that said ST. CLAIR LAKE—without hearing the question ring.

The once-unthinkable began to wade into the realm of possible. The assistant county prosecutor leaned back in his chair, silver-framed diploma glinting, and said the word no one wants linked to the dead: exhumation. There were protocols, forms, a judge’s signature. The funeral director’s dry voice over the phone. The hospital compliance officer’s clipped email. A deputy’s suggestion that the family consider a counselor. In the end, the order was signed with ink so blue it looked like a bruise.

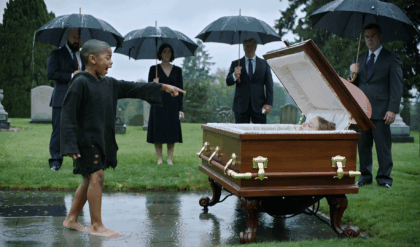

They gathered at Maple Grove Cemetery on a skyless morning in late October when the oaks were freckled rust and the ground had that stiff, crusted feel that told you winter was waiting behind the barn. Daniel wore his work boots and the only black coat he owned. Ethan stood with both hands jammed into the pockets of a jacket Sarah had knit with orange piping he’d never liked until it became the last thing his mother made.

Cemetery workers laid down plywood sheets. A backhoe groaned. Neighbors averted their eyes or stared too openly from the edge of the gravel lane. The deputy coroner, Dr. Anika Sharma, kept her face neutral, a measured kindness in the way she spoke to Ethan:

“We’ll proceed carefully. You don’t have to watch.”

“I want to,” Ethan said. His voice carried into the cold like a vow.

The coffin rose, heavy with earth, pale wood smeared the color of tea. Daniel’s throat closed. He reached for Ethan’s hand and felt a small, fierce squeeze—how strange that the hand that once fit inside his palm now steadied him. When the coffin settled on the boards, the coroner gave a quiet nod to the cemetery crew.

The pry bar kissed the seam. Screws loosened with tiny metallic cries. The lid creaked, every inch a corridor of dread, until it finally came open.

Daniel didn’t breathe. He didn’t hear the murmurs around him. He saw only his wife—what time had done to her—and then the thing that cut through his ribs like a thrown nail.

Sarah’s hands were lifted toward the lid, fingers bent into clawed parentheses. Her nails were split and ragged, crescent moons caked with blood. The underside of the lid was scored with frantic scratches, a desperate grammar written in wood. Her mouth was open in a shape Daniel had never seen on her—a silent sob that would never reach air.

Somebody gasped. Someone else swore. The deputy coroner’s breath shortened, then steadied. Ethan’s knees hit wood and Daniel hauled him close, pressing the boy’s face into his chest as if a father’s body could be weather.

“She didn’t die in peace,” Ethan choked. “They put her there while she was still—”

“I’m here,” Daniel said, useless words against an unforgivable fact. The ground swayed. The world narrowed to the scent of wet pine and dirt and the chemical sweetness of embalming that hadn’t done its job fast enough to outrun terror.

Dr. Sharma’s voice came clipped, professional, quickly layered with instructions—photograph everything, preserve the lid, minimize air exposure, secure the coffin for transport. A deputy read from a checklist. A flurry of hands and brown evidence bags. Someone took Daniel’s elbow, a soft pressure back toward the path, and he realized he’d been saying Sarah’s name out loud like a person lost in a warehouse calling for the lights.

News moved faster than decency. By the time the hearse doors shut, a man with a camera from Channel 6 stood behind the metal fence, overcoat collar turned up against the wind, speaking into a microphone with his polite I’m-so-sorry eyes. The phrase spread in murmurs and in headlines: buried alive. The words felt like a wrong thought that couldn’t be unthought.

That afternoon in a small conference room at the Franklin County Coroner’s Office, Daniel and Ethan sat with Styrofoam cups of coffee that tasted like hot paper while Dr. Sharma explained what she could without breaking the case, her voice the kind of steady that makes you trust the speaker even when your insides are rope.

“There are rare presentations,” she said, “that can mimic death—cataleptic states, profound hypothermia, certain neurologic phenomena. I can’t make determinations yet, but given the evidence at the gravesite, we have to consider the possibility that Sarah regained consciousness after interment.”

“Possibility?” Daniel asked, the word splintering.

“I have to speak in possibility until the autopsy is complete,” Dr. Sharma said. “But I will tell you—what we observed is consistent with a struggle inside the coffin.”

“Jesus,” Daniel whispered. He pressed his palms to his eyes until sparks moved across the black.

Ethan sat up straighter, the cup in his two hands like a small prayer he didn’t believe in. “So I wasn’t crazy,” he said, looking not at Dr. Sharma but at his father. “I saw her hand. That day. I told you.”

Daniel felt the sentence land like a nail he had driven crooked, now prying loose with the claw of memory. “I’m sorry,” he said. It sounded too simple to live next to that much pain. “I should have—”

“You believed me in the end,” Ethan said. He was trying to save his father from drowning and it made Daniel love him so hard he felt bruised by it.

The following week turned their house into a train station with no timetable. The doorbell rang in expectant trios. Reporters waited on the curb behind orange leaves and black tripods. A woman from church brought a casserole and didn’t make it past the porch because Daniel could not let anyone cross the threshold with hands that didn’t know the feel of Sarah’s coffee mug. A lawyer’s card appeared in the mail slot in a stiff white envelope. Strangers sent letters in careful block print that said things like my aunt once and there’s this thing called the Lazarus phenomenon and I am praying for you.

At night Daniel lay awake and replayed the days around Sarah’s death, rerunning the edges, looking for the snag that had pulled the whole sweater out of shape. He saw the day she collapsed in the kitchen, her left hand dropping the bag of groceries, onions rolling like little moons. He saw the paramedics moving with practiced speed, the hospital hallway with the scuffed baseboards, the doctor with the clipped beard saying, “I’m sorry. We did everything.” He had accepted the statement because accepting meant he could walk from the room without falling down.

Now he replayed the doctor’s eyes. Had they looked away? He remembered a nurse who had said, “Sir?” as if she wanted to say something else and then didn’t. He remembered signing something he didn’t read.

On a damp Tuesday, Daniel took the lawyer’s card to a brick building near the courthouse with a brass plate that said WHITAKER & LOWE. He chose that card because the partner’s first name—Ava—was the name Sarah had wanted if they’d ever had a second kid, and because superstition becomes reasonable when your wife has scratched at the roof of a coffin.

Ava Whitaker was mid-thirties with a knot of dark hair at the back of her head and a way of testing silence before she spoke into it. Her office had no diplomas on the wall, just a framed black-and-white photograph of a narrow bridge over a river in winter.

“I don’t bring cases I can’t carry the distance,” she said when Daniel finished halting his way through the story. “And I don’t take cases to the press. If we do this, we’ll do it for Sarah and for every patient who will come after.”

Daniel’s jaw worked. “They put her in the ground alive,” he said. “I can still hear the sound of—” He shut his eyes. “I want someone to answer for that.”

Ava nodded. “I’m going to request Sarah’s complete medical record—EMS run sheets, ED notes, nursing flowsheets, vitals, medication administration records, ECG strips, code logs, time-of-death pronouncement checklist. The hospital will fight me. We’ll get a protective order. We’ll depose everyone who touched your wife or a pen that day.” She leaned forward, clasped her hands. “I’m also going to tell you something you won’t like: it’s possible this is not a single person’s fault. It is often a cascade—a system that allows tired, overworked humans to make terrible mistakes. We’re going to find out which mistakes were made.”

Daniel swallowed. “Okay.”

“I need you steady,” Ava said. She turned to Ethan, who sat beside Daniel in a chair too big for him. “And I need you brave, Ethan. I’m sorry you have to be.”

“I already am,” Ethan said. He looked like he didn’t believe it until the words left his mouth, and then his shoulders settled, as if saying them turned them true.

The investigation widened. The hospital hired a downtown firm with glass conference tables and dark suits and a reputation for making bad facts smaller. The funeral home produced records that read like a grocery list: receipt of remains, transfer to prep room, embalming incomplete at the family’s request, sealing of casket. In that stack, they also found something Daniel would replay as often as the tug at the graveside: a notation by an apprentice embalmer that said in halting script, “Appearance of breath or movement?” with a question mark and then a line drawn through the entry in darker ink. When asked, the apprentice said he had been scolded for using imprecise language; what he meant was a “postmortem reflex,” a phenomenon he had learned to call it because saying it out loud was easier than believing what he thought he saw.

Ava subpoenaed the hospital’s “pronouncement checklist.” What came back was a single sheet with boxes marked asystole, unresponsive to painful stimuli, pupils fixed and dilated, no spontaneous respiration. The time was recorded as 3:49 p.m. There were initials next to each box. The attending physician, Dr. Leonard Price, had signed the bottom.

In deposition, Dr. Price sat with the composed unhappiness of a person trapped between truth and job. Ava’s questions landed with the relentless kindness of a metronome.

“Doctor, at 3:40 p.m., Sarah Miller had what signs?”

“She had no palpable pulse,” he said. “No respiratory effort. No corneal reflex.”

“Was a Doppler used to confirm pulse absence?”

“No.”

“Capnography?”

“At that time, it was not our standard to maintain capnography after cessation of resuscitation.”

“And how long did you observe before pronouncement?”

“Ten minutes.”

“Did anyone check again at 3:49 p.m.?”

He exhaled. “No. The family was present. I believed it would be cruel to place hands on her again.”

“You checked the boxes.”

“Yes.”

“The ECG strip printed asystole at 3:44 p.m., correct?”

“Yes.”

Ava held up a cropped photocopy of a strip. “Doctor, what do you call this artifact?”

“Baseline wander.”

“And what causes baseline wander?”

“Loose electrodes. Motion. Patient respiration.”

She let that sit. “Motion,” she repeated quietly. “Patient respiration.”

A tremor went through Daniel that he could not blame on coffee. The hospital’s attorney objected to form. The court reporter’s hands danced over the keys like a piano that had learned to translate pain into transcript.

“Doctor Price,” Ava said, “has your hospital ever implemented a two-physician pronouncement policy in ambiguous cases?”

“No.”

“Does your hospital require a post-pronouncement monitoring period?”

“No.”

“Did anyone consider the possibility of catalepsy?”

“No.” A pause. “The presentation was consistent with cardiac arrest.” He stared at the table. “It… appeared to be.”

Afterward in the hallway, Ava put a hand on Daniel’s forearm exactly once, like a pledge rather than a comfort. “We’re going to need a whistleblower,” she said. “There’s something we aren’t seeing.”

They didn’t have to wait long. A woman in navy scrubs approached Daniel in the grocery store parking lot one gray afternoon while Ethan was inside choosing cereal like it mattered what your breakfast was when your mother had died twice.

“Mr. Miller?” she said, voice low. “I was on your wife’s code team.”

Her name was Lily Rojas. She was in her twenties, hair tucked under a knit cap, eyes moving like a person who’d gone on record in her head and was only now stepping into the ink.

“I charted that your wife had no response to painful stimuli,” she said. “The doctor called time. Families often want to be alone and we try to give that. But Sarah’s hand—” Lily stopped. “Sometimes there are movements. Agonal reflexes, nerves firing. We’re taught not to confuse families.”

“What did you see?” Daniel asked.

“Her fingers flexed.” Lily’s face had the misery of a person who had loved the wrong person once and now loved correctness too much. “The lead on the ECG had loosened earlier—she was sweaty, we’d suctioned, her skin was damp. I tightened it. We were supposed to call engineering to fix the monitor mount. We hadn’t. We were short-staffed. I should have said something else out loud.”

“You came to me now,” Daniel said. He thought of how Sarah would have hugged this young nurse the way she folded in people who didn’t get hugged enough. “That counts.”

Lily nodded like it didn’t but she wanted to believe it might. “There’s a nurse manager who told us never to use the word movement in the family’s hearing. We call everything artifact. Because it’s safer.” She looked at him. “I’m sorry.”

Ava moved quickly. She filed a motion to compel the hospital to produce incident reports and internal emails. The judge—a woman with tired eyes and a white streak in her hair that made her look fierce even when she wasn’t speaking—read the hospital’s arguments and then granted most of Ava’s requests with a phrase Daniel came to love: narrowly tailored but sufficient.

What arrived was a stack that smelled like copier heat. There were emails about staffing. A maintenance ticket for a monitor mount. And in the middle, a short message from a compliance officer to the attending physician time-stamped two days after Sarah’s death:

“Please ensure future pronouncements follow checklist. Consider second physician signature in complex presentations. Recent family interaction indicates confusion about status at time of pronouncement.”

“Confusion,” Daniel said in Ava’s office, the word tasting like dry bread. “They called it confusion.”

“They often will,” Ava said. “Because the alternative has too much gravity.”

The press did what the press does when a story has a sentence that fits under a photograph. The Columbus Dispatch ran a front-page above the fold with a picture of Daniel and Ethan walking between rows of headstones under the bland sky of a late November that wanted to be snow. A national cable show invited Daniel to sit in a studio under lights and say words like accountability and standards of care. He did it because each time he said Sarah’s name into a microphone, a corner of the world learned to say it back.

Within a month, an Ohio state representative from Toledo named Ruth Blakely introduced a bill. Everyone called it Sarah Miller’s Law because saying “House Bill 314” felt like misplacing a person. The proposed statute required two independent clinicians to pronounce death in the emergency department for non-traumatic arrests, mandatory ten-minute capnography post-resuscitation to verify apnea, and a thirty-minute observation window in ambiguous cases before the body could be released. It also offered grants to rural hospitals to purchase portable ultrasound machines and capnographs and required documented confirmation of electrode integrity on ECG monitors during pronouncement.

Hospital associations hated it for all the reasons you think—cost, workflow, the implication of guilt. Families loved it for all the reasons you hope—because laws are sometimes fences you put up around the place where something awful happened so it doesn’t happen again.

Daniel had never been inside the Statehouse. He stood under the rotunda, the dome like a white rib cage above him, and waited to speak into a microphone with a blinking red light. Ethan wore a suit that made him look like a boy dressed as a man for Halloween, and stood with his hands clasped because adults told him to when they didn’t know what else to ask of a child in a hard place.

“Sarah was my wife,” Daniel said. “Ethan’s mom. She taught piano lessons on Saturdays and would leave a note on the counter that said ‘call me if you remember where the tuner went.’” He smiled without joy. “She was buried alive. I need you to hear that sentence as if it had your last name in it.”

He paused. The committee room was too cold; why were government rooms always too cold? He found the eyes of one representative who had the expression of a man remembering his grandmother’s hands. “This bill is about time,” Daniel said. “Time to be sure. Time to say hold on, what if. If these steps had been in place, a second physician would have stood next to Dr. Price. A capnograph would have traced on paper for ten extra minutes. A nurse wouldn’t have had to decide whether to say the word movement out loud. We might have bought enough minutes for Sarah to breathe.”

Outside, in the bright iron clang of TV rigs and microphones, a reporter asked Ethan, “What do you miss most about your mom?”

“Her voice,” Ethan said. He didn’t elaborate. The world filled in the rest and for once it did it right.

Grief is not a straight road but a room you keep re-entering through different doors. It smelled like sawdust for Daniel, like the inside of a pickup in winter, like the breath of his boy when he fell asleep on the couch under the flannel blanket Sarah had insisted he keep even when the dog chewed the corner. He went back to work because bills didn’t cancel themselves; he poured concrete and framed walls and listened to men talk about basketball games and aches that had first names. They watched him for the first week like he might drop a hammer on his foot, and then they stopped watching because men didn’t know what to do with watching, and maybe because Daniel started showing up with a steady enough hand.

At night, he and Ethan made dinner with a precision that would have made Sarah laugh. They measured out salt like it mattered, folded napkins even when paper would have done, placed the fork on the left and knife on the right because Sarah had always said ritual wasn’t just for churches. They hung her scarf over the back of her chair. They didn’t move it for a long time.

Ethan started therapy on Thursdays in a building with a waiting room that had a fish tank he pretended not to care about. His therapist was a man named Renner who wore socks with tiny guitars on them and never wrote anything down when Ethan talked. They talked about nightmares where dirt pressed like a mattress on his chest, and about how telling the truth is not a magic spell but it can be a door.

On a day when snow threatened and then changed its mind, Renner said, “Your mom’s story got bigger than your mom.”

“I didn’t want that,” Ethan said.

“I know,” Renner said. “And also—look what it might change.”

“Dad says the bill might save someone.” Ethan twisted the drawstring of his hoodie. “Then maybe the bad thing isn’t only bad.” He frowned. “Is that stupid?”

“It’s brave,” Renner said.

The bill crawled like bills do. Hearings, markups, compromises that tasted like diluted soup. The hospital association shaved off the observation window from thirty minutes to twenty. The second-signature requirement became a “second-clinician confirmation” that could be a nurse practitioner in rural hospitals. Capnography stayed. There were grants for equipment that everyone knew would run out by the time the ribbon was cut on the press conference. The version that emerged was smaller, but it was not nothing.

In the middle of winter, a judge set a trial date in the civil case. The hospital’s attorneys tried to postpone. Ava didn’t let them. She walked into court like someone who kept her promises the way other people kept family recipes.

The courtroom smelled like polish and old paper. A portrait of a dead judge frowned down on everything. The jurors looked like Ohio—wool coats and church clothes and one guy in a Bengals tie who wasn’t going to take it off for anyone. Opening statements were the soft core of a hard fruit; they offered sweetness while the knife did its work.

Ava told the story without adjectives. “At 3:49 p.m., Dr. Leonard Price pronounced Sarah Miller dead. He did so without capnography, without Doppler confirmation, with one set of eyes and a checklist designed for convenience, not safety. Sarah was then placed in a coffin. When her casket was opened six weeks later, her hands showed signs of struggle. This case is about a system that created the conditions for that outcome.”

The hospital’s lawyer, a tall man who wore his hair as if he expected strong wind inside, said words like “rare,” “unprecedented,” “tragic,” and “not negligence.” He used the phrase “unfortunate ambiguity.”

Witnesses came like pieces of the same shattered bowl. Lily Rojas testified with her hands in her lap and a tremor that went away when she started describing the monitor. The apprentice embalmer cried once and then kept going. Dr. Price sat with his integrity bleeding in public and told the truth the way people do when they have stopped protecting themselves and started protecting whatever’s left of the profession they went into to keep people alive.

Under cross, Ava asked the questions she had asked before, sharper this time. “Doctor, is there any reason capnography would be harmful?”

“No.”

“Any reason a second set of eyes would be harmful?”

“No.”

“Any reason the phrase ‘patient movement’ should be erased from the language?”

He looked at the jury. “No,” he said, and Daniel understood in that moment that this man had been drowning too.

When it was Daniel’s turn, he walked to the witness box as if it were a high roof and speaking were a line he had to cross. Ava asked him to tell the jury about Sarah. He did—her laugh that started big and then got quiet, the way she put her hand on the back of Ethan’s neck at the baseball field when she wanted him to focus, her meticulous grocery lists that always included the phrase “nice bread” because she believed good bread made bad days hospitable.

“And what did you see when the coffin was opened?” Ava asked.

Daniel told them. He said the sentence he had never wanted to learn to say. He kept his voice even because he saw Ethan in the second row between two women who could have been his teachers, and he wanted his boy to learn that a man can hold the walls up even when the house is made of pain.

In cross, the hospital lawyer asked if Daniel had considered that he might be projecting, that grief could make a person see what he feared. Daniel didn’t flinch. “You weren’t there,” he said. “If you had been, you wouldn’t ask that question.”

The coroner, Dr. Sharma, explained the science and the limits of it. Time had blurred some signs but not all. The scratches were there. The blood under Sarah’s nails contained her DNA and wood fibers. There were small abrasions on her fingertips consistent with attempts to pry or dig. The precise time of that struggle could not be known. Science had words for many things; it did not have a precise word for terror inside a small dark space.

Ava ended with the chart.

“Is it more likely than not,” she asked Dr. Sharma, “that Sarah Miller was alive when she was placed in that coffin?”

“Yes,” Dr. Sharma said.

The jury went out. Daniel sat with his hands flat on his thighs, feeling the warmth of his own muscles and the way adrenaline makes you cold. Ethan held his breath the way kids do when they go under in a pool. Time unspooled. The second hand on the courtroom clock was too loud.

When the jury came back, the foreperson read a number. It didn’t make Sarah breathe again. It made other things possible—the scholarship Ava had suggested they create in Sarah’s name for nursing students who promised, in writing, never to call movement artifact when their gut clenched; the fund to help rural ERs buy capnographs; the bench outside the hospital with a small plaque that said SARAH’S BENCH—STOP, LISTEN, CONFIRM.

Money couldn’t hold a hand in the middle of the night; it could hold a door open.

After the verdict, Dr. Price approached Daniel in the hallway where everything important seems to happen. He didn’t offer his hand. He looked like a man who’d gone outside without a coat. “I’m sorry,” he said. “There’s not a word big enough.”

“There isn’t,” Daniel agreed. He found he didn’t want to push the man off the metaphorical roof. “I hope you don’t ever do it that way again.”

“I won’t,” Dr. Price said. He looked at Ethan and said, “I am sorry,” and Ethan nodded once like a judge accepting a plea.

In March, Sarah Miller’s Law passed with bipartisan support because grief doesn’t have a party. The governor signed it at a table in a room with flags and bad coffee. Daniel stood behind him, hand on Ethan’s shoulder. The pen was cheap and the cameras were many. It felt like not enough and also like something, the way a fence is something even if the field is already cut.

Spring came stubbornly. Lilacs took their time. Daniel and Ethan dug a hole in their postage-stamp backyard and planted a dogwood tree because Sarah had once pointed at one in a nursery and said, “If we ever get a tree, it should blush in April.” They tamped the dirt with care, as if they were tucking in a child. They tied the trunk to a stake with a piece of soft cloth cut from one of Sarah’s old T-shirts.

Life, like a stubborn engine, turned over. Ethan hit a double in Little League that made the coach shout like a man who had just saved a life, and afterward, Ethan sat on the tailgate and ate a cold slice of pizza and said, “Mom would have told me to keep my elbow up,” and Daniel laughed for the first time in a long time in a way that wasn’t a cough.

One evening in late May, Daniel cleaned the garage because grief sometimes needs things sorted. He found a dusty banker’s box labeled “Sarah—piano stuff” and inside, under sheet music for Debussy that had notes in Sarah’s looping hand (circle this, emphasize left), he found a notebook. The first page held a list of students and times and the scribbled note “ask Mrs. Holland about recital space.” The second page was a recipe for bread with the words “nice bread matters” underlined twice. And in the middle, halfway back, folded like a letter to the future, was a page that said, in Sarah’s voice that Daniel heard by reading it:

If something happens to me, make sure Ethan knows how to tune middle C with a tuning fork. It will sound wrong at first and then it will sound like a room you remember. Daniel, please don’t let the house get too quiet. Tell jokes in the kitchen even if nobody laughs. Plant a tree that blushes. Don’t forget nice bread. If I’m gone, I am not gone. You know what I mean.

Daniel sat on the concrete floor with the notebook in his lap and breathed in sawdust and old baseballs and the memory of her hair when she leaned over the sink to laugh. He took the page inside and read it to Ethan, and Ethan said, “She knew we’d need directions,” and Daniel said, “She always did.”

Summer wrapped the town in green and thunderheads. The bench outside the hospital gathered names like a quiet church. People sat and cried and didn’t. Parents told children to please not jump on the plaque and then took a photograph because that’s what you do when you want to remember the fact of a place even more than the place. Nurses ate lunches there, pale-green scrubs bright in the sun. One afternoon, Lily Rojas sat on the bench and sent Daniel a text with a picture of her name badge next to the plaque. The message said: Started capnography training for new hires today. We say the word movement out loud.

Ava came by the house on a Saturday with a loaf of something her partner had baked and a folder with the scholarship paperwork. They signed things. They ate the bread. It was, as Sarah would have insisted, nice bread. They told stories about the strange club you join when you’ve taken the worst thing a system can do and turned it into a lever.

“Do you think it’s enough?” Daniel asked Ava as the sun went copper over the dogwood.

“Enough is a moving target,” she said. “But it’s further than we were.” She looked at Ethan flipping a baseball up and down like a metronome for courage. “He’s further than he was.”

On a warm night in August, Daniel and Ethan drove out to Maple Grove with a bouquet of grocery-store flowers because grief doesn’t always require roses. The cemetery was almost empty except for a couple walking a slow white dog and a teenage girl stretched on the grass next to a headstone, earphones in, a living person finding a way to be in a room with the dead.

They stood in front of Sarah’s stone. The ground above it had settled, the harsh rectangle softened by clover. The little metal vase the cemetery provided was slightly bent where the mower had nudged it. Daniel straightened it with two firm hands and didn’t curse because you can curse at a mower or you can straighten the vase; you can’t do both.

“Hi, Mom,” Ethan said. He cleared his throat. “I read The Giver for school. I thought it would be boring and then it wasn’t. I think you would have liked that ending and also maybe hated it? Renner says I can think both at the same time.”

Daniel looked at the words on the stone: SARAH ANN MILLER. WIFE. MOTHER. MUSIC TEACHER. BELOVED. He wanted to add: LAW. BENCH. BREAD. He settled for touching the top of the stone like a person checking the hood of a car to see if it’s still warm.

“I keep thinking about time,” he said, not sure if he was talking to Ethan or the stone or the sky with the one visible planet that wasn’t a plane. “How much difference ten minutes can make. Twenty.”

Ethan nodded. “Renner says the ten minutes after something bad are like a second chance wrapped in paper you don’t want to open.”

Daniel smiled. “He’s a therapist, all right.”

They left the flowers, slightly lopsided in the wind. They walked back to the truck through the aisles of names, past a pair of boys in team shirts placing a wreath at a stone that had the word COACH carved on it. Life is the long walk you take back to the car after you’ve said something to someone who can’t answer.

In September, the scholarship fund gave its first award. The recipient was a nursing student at Ohio State named Maya Kline who wrote an essay that made Daniel cry on the porch and then laugh because the last line quoted Sarah without meaning to: “In the emergency department,” she wrote, “nice bread matters—it’s what we call the little things we do that make hard days human. I promise to be the kind of nurse who says movement out loud.”

Maya came to the house with her parents to say thank you and did the thing midwesterners do where they bring something to thank you for the thing you did to thank them for something. It was a blueberry pie in a tin plate that dented when you looked at it. They ate it at the kitchen table with paper plates and used forks and everybody agreed the crust was worthy, and Daniel found that the room didn’t feel as quiet as it once had. He said the word future and didn’t feel like a thief.

The dogwood blushed. The bench gathered more names. Sarah’s law reduced the number of pronouncements made by a single physician in EDs across the state by numbers that made a difference. A rural hospital in Vinton County used the grant to buy a capnograph that beeped at the right moment one night when a man who looked like everybody’s uncle wasn’t done breathing yet.

Once, in a grocery line, a woman behind Daniel tapped his shoulder and said, “Are you—”

“Yes,” he said, not because he loved the recognition but because the rest of the sentence mattered.

“My sister,” the woman said, blinking quickly, “had a thing with her heart, and they kept her a little longer because of the new rule. She woke up.” The woman’s breath hitched. “So.”

Daniel reached for his wallet and then didn’t because money wasn’t the thank-you here. “I’m glad you have her,” he said. And later, when he told Ethan, the boy listened with his head tipped, and then went out to the dogwood and stood there a long time like a kid listening for something in the leaves.

On the first anniversary of the exhumation, Daniel woke before dawn because grief is muscle memory. He and Ethan drove to Maple Grove with travel mugs of coffee and hot chocolate. They stood by Sarah’s stone in the bluish morning and waited for the first sound of day—the bird that goes before the others like a good foreman who shows up early to unlock the gate. A breeze moved over the ground and the grass topped with dew made the sound of a word you could almost hear if you tilted your head the right way.

“What did you dream last night?” Daniel asked.

“That I was underwater,” Ethan said. “But I could breathe this time.” He looked at his father. “We could both breathe.”

Daniel put his arm around his son’s shoulders. “That’s the right dream.”

They stood there until the sun came up and turned the headstones into rectangles of light and shade, and then they went home and made French toast because that’s what you do when the light gets in.

That afternoon, they tuned Sarah’s old piano. It took longer than it should have because the tuning fork did sound wrong at first, and then, gradually, it sounded like a room they remembered. Daniel sat on the bench he and Ethan had sanded and varnished together, and placed his hands on keys he had never learned to play. “Show me middle C,” he said.

Ethan tapped it gently. The sound was small and right. He looked at his father and smiled a real smile that reached his eyes.

They played with one finger each until the notes linked up into something you couldn’t call a song but might someday. The house wasn’t quiet. The house would never be quiet again in the way quiet had meant before. It was a different quiet now—the kind that holds the world the way both hands hold a cup that’s too hot and just right.

On a Tuesday a little while later, Daniel took the notebook page of Sarah’s instructions and had it framed. He hung it in the kitchen by the calendar with the barn and the Buckeyes schedule, and underneath, on a small shelf, he set the tuning fork and a wrapped loaf from the bakery with the big windows on High Street. He wrote on a scrap of paper and tucked it behind the frame where it would slip out sometimes when the door slammed: You’re not gone.

If you were to drive down their street in Worthington on a Saturday in late fall and slow at the house with the dogwood, you might see a man on the porch steps with a cup of coffee and a boy hurrying down the walk with a baseball glove, and you would think: ordinary. You would be right. It is the most sacred word anyone can earn after the worst thing. A man and his son, in Ohio, where laws change slowly and trees blush in April and the sound of middle C can still be found with a simple fork of metal and a patient ear. And if you listened very closely, the way a boy taught himself to listen because he once heard a thing no one else did, you might hear the quiet knock the wind makes under the eaves, and you might think for half a second it was coming from under the earth.

It isn’t, not anymore. It is coming from inside the house, from the kitchen where the bread is cut thick and the dogwood can be seen in the window and someone is laughing at a joke that isn’t funny because love makes jokes funny enough. It’s coming from the piano, from a note that was wrong and then became right. It’s coming from the bench outside the hospital where a nurse is on her lunch break whispering, “Say it,” to a student, and the student nods and does. It’s coming from a law with a woman’s name on it and a boy who learned to breathe underwater. It’s coming from the life that kept going.

The bench will darken with weather. The metal plaque will tarnish and then get polished and then tarnish again. The dogwood will add rings. The page in the frame will fade toward the edges, as all paper does. But the words on it—nice bread matters, tune middle C, don’t let the house get too quiet—will keep their shape, and anyone who knows how to listen will hear what we mean when we say someone is gone and also not.

On a Sunday in December, the first snow fell. It lay on the dogwood like a white shawl. Daniel and Ethan returned from church with red ears and the sense of a day that could hold something good. They kicked their boots on the mat, shook off the cold. They put a pot of chili on the stove and set out bowls. They did not say grace, exactly; they let the steam say it for them. Ethan ladled spoons and said, “Nice bread?” and Daniel smiled and cut slices. From the radio on the counter, a game announcer’s voice rose and fell under commercials for carpet cleaning and car dealerships. Ordinary. The sacred word.

When dusk came early, as it does in December, Daniel flicked on the porch light and watched the snow come down hard enough to blur the mailboxes. He heard the piano. Ethan had gone into the living room and was working a halting melody toward something like a carol. The notes were uneven, that beginner’s stutter that has its own kind of grace. Daniel stood in the doorway and didn’t interrupt.

He looked at the walls they had painted a sky color because Sarah said it made Ohio winters survivable. He looked at the T-shirt tied to the stake of the dogwood outside, now frozen into a small flag. He looked at the tuning fork on the shelf, at the framed note that held his wife’s handwriting thinner now where the ink had spread under glass, and at the space in the air that was not empty.

“Dad?” Ethan called.

“Yeah, buddy?”

“Come sing the easy part.”

Daniel stepped into the room and sat on the bench. He did not have a good voice and no one complained. They found the melody together. The house held them. Outside, snow did what snow does—covered what should not be stepped on, quieted what needed quiet. Inside, the knock that once came from the wrong place now came from the right one, a soft percussion under everything, a heartbeat, alive, alive, alive.