On the kind of December morning when Boston’s low sky pressed down like a lid, Robert Hale walked with his collar up against the Atlantic damp and pretended not to notice the ache that woke with him every day at five. The ache had a name—Lydia—and three winters had not dulled it so much as taught him to arrange his hours in obedient rows: reports at dawn, a breakfast he did not taste, a phalanx of meetings that marched from quarter-hour to quarter-hour across a calendar no one else controlled, then the long, dark glide back to an empty Beacon Hill townhouse where silence waited with its lights off.

He had an umbrella tucked under his arm though the rain did not quite fall—only hung, the air granular with it. He cut through Downtown Crossing toward a meeting with a sovereign wealth fund whose representatives had flown in on a jet that would depart within the hour. They wanted to buy a platform in Hale Foundry Systems—not the furnaces of another century, but the cloud architecture that ran heat, airflow, and predictive maintenance for the concrete skeletons of modern cities. He knew the number they would say before they said it. He knew the counter. He knew, already, that he would say yes.

Knowing made no difference. The city’s pulse did not quicken; the carved cornices above Winter Street did not look up from their century of weather to applaud. He walked past the shoe-repair kiosk where a red sign promised while-you-wait miracles, past the steamed windows of a bakery where someone laughed, past a saxophonist tonguing a minor blues under a scaffold. He was two blocks from the Federal Street tower when he heard it. Not the sax, not the hiss of traffic. Crying.

It threaded the noise without asking permission, a small, tight sound as if a throat were trying not to make it. He stopped. Robert had long ago learned the city’s policy toward other people’s trouble: keep moving. He had honored the policy. He had walked past men arguing on curbs, past lost tourists spinning a map like a broken wheel, past the woman who slept every October in a cardboard house outside the Tremont Street church and folded it up like an altar every morning. There were, one told oneself, systems.

But this sound—this held-back, never-learned-how-to-cry-right sound—got under the bone.

He followed it into a narrow service lane that ran between two brick buildings. Trash barrels. A fire escape rungs-slick with mist. The lane held its own light, the gray kind that makes color look like a rumor. At the end of that short, echoing world sat a girl on the wet concrete. Eight, maybe nine. Brown hair in ropes, cheeks streaked, jeans greased with street. In her arms lay a smaller child—a baby just past the age when the word baby seems too small to hold the person—limp as a doll that has lost its mind.

The older girl looked up because she felt him looking. Her eyes were brown, raw, the kind of brown that once had shone. She spoke with the ceremony of someone who had rehearsed words in terror. “Sir,” she said, “can you—can you bury my sister?”

Robert did not kneel yet, did not move; there is a kind of stillness that arrives before action, the body’s last check before it spends itself. The girl went on, as if silence were a thing that could be paid down with words. “She didn’t wake up today. She’s cold. I don’t got money for, like, a nice… for anything. I can work. I’ll pay you when I’m big.”

He had walked through rooms where a billion dollars changed hands and called those rooms ordinary. This request, made in a lane that smelled of damp cardboard and sugar, knocked his breath out. The mind does what it can when it cannot understand; it looks for forms. He looked for an adult—someone who belonged to the girls—someone to whom he could turn and hand back the fact—someone who could tell him what to do. There was no one.

He placed his umbrella on the ground like a white flag and went to one knee. The baby’s face was too still. Her lips were a pale, dry seam. He touched two fingers to the soft notch of her neck with the reverence of a man reaching for a live wire. Long seconds. Nothing. Then—a quiver under the skin, the faintest beat, a thread that might be life.

“She’s alive,” he said, and his voice came out like a thing that had been kept too long in a drawer. The older girl’s hands tightened; her whole body seemed to lean toward hope as if it were a fire. “Are you sure?” she whispered. “She got so quiet. She never does. I tried—” She swallowed. “I feed her first. I do.”

Robert was already pulling his phone one-handed from the inside pocket of his coat, fingers clumsy on glass. He didn’t think; he dialed Mass General because that was where he had written checks with Lydia’s name on them after Lydia could not be saved. The operator put him through to the pediatric ER, and he did not bother to say who he was. He said, “I’m two blocks away with a child in respiratory distress—two years old—hypothermic, likely pneumonia, possible severe malnutrition. I’m bringing her now. You’re going to meet me at the circle.”

He scooped the little one from the girl’s arms. The weight startled him. Too light, he thought, and a static came into his ears. The older girl stood with him fast, as if fear were gravity and he were the heavy thing. “Come,” he said, and the word came out rough and more command than invitation. “You’re with me.”

He hustled back through the lane into the busier light. A bus honked. A cyclist swore. The world had opinions about right-of-way and none about this. He got them into his black SUV, fastened the older girl’s seat belt with hands that remembered other small adjustments—mittens slid over small hands, a hair elastic twisted twice and not too tight—and eased the baby across his lap to keep her upright while he drove.

“Talk to me,” he said to the girl. “What’s your name?”

“Leah.” The syllable was soft, a leaf that had fallen through air for a long time.

“Leah, I’m Robert. Tell me your sister’s name.”

“Julia. But mostly I call her Jewel.”

He let that sharpen him. You do not name something Jewel unless you mean to keep it. The lights were with him and the traffic parted as if the city secretly admired emergencies performed with competence. They came up Cambridge Street in a wash of gray and arrived at the ER circle to find a nurse with a warming blanket and a respiratory therapist with a bag-valve mask. Robert handed Julia over, and the therapist’s big gentle hands made her look even smaller. Leah did not let go of the cuff of Robert’s sleeve.

Inside, time changed shape. There are places where the minutes act like soldiers, and places where they act like animals. In the pediatric bay, minutes snorted and bucked and then lay down for long stretches while machines breathed and numbers climbed by half-points. A doctor introduced herself as Dr. Joshi and did not waste sympathy on preliminaries. She said pneumonia out loud. She said refeeding syndrome as if explaining the ocean. She said IV antibiotics and warmed saline and oxygen and monitoring and “We will do everything.”

Leah sat on a plastic chair with her knees together and her fists on her thighs like someone expecting a test she could not study for. A social worker with a square badge that read MARTA TORRES approached and asked Robert, “Are you the guardian?” Protocol was a room with its own doors.

“No,” he said, too dry. “No, I’m the man who found them.”

“Then we’ll need your information. And hers.” Marta’s voice had two layers: official and tired. “Child Protective Services will be contacted. We have to. There are… processes.”

Leah’s head flicked between them. Robert felt her fingers notch deeper into his sleeve. He gave his name and number and the Beacon Street address he had said out loud a thousand times to food delivery apps and never to a child who might need it. He did not sit. He asked for coffee and did not drink it. He read the whiteboard where someone’s green handwriting made a tiny sky of plan: ABG, CXR, 38.1°, 4 liters O2 via NC. He said nothing about the numbers. He stayed.

Night fell while some other part of the hospital watched the Patriots lose. The ER ceiling glowed steadily, a pale noon. Robert stood at the foot of Julia’s bed and listened to air move. He did not pray; the last time he had prayed it had been for Lydia’s fever to break, and instead of breaking it had grown a crown. He did what he could: he made the doctors’ work simpler by not interrupting it. He took Leah to the vending machines for graham crackers and a bottle of apple juice, then returned them both to the noise and light.

“How long,” he asked, “have you been… where you were?” He would not say homeless; the word did not feel like a thing to put onto a child without asking permission.

Leah picked at the plastic label of the juice. “Since my grandma… before Thanksgiving. She was good. She had a couch. And she made eggs at night, like breakfast but at night. And she said I had to read out loud, even if it’s dumb stuff like old mail.” Leah’s mouth pulled in briefly, the way a lip pulls when you are trying not to wobble. “The lady took her away in a truck that makes noise. Then the apartment was not ours anymore.”

“Your mother?” Robert asked, and she shook her head a short, hard no. “Was with some guy. I don’t… it wasn’t good.”

“And your father?” He knew, hearing himself, that he was filling a form.

“Don’t know.” She held up the juice bottle with both hands and took a careful sip as if the bottle were a chalice. “But I can do stuff. Like I watch the little one. And I found the good corner by the bakery because the air’s warm there and there’s little sugar in it.”

“You did good,” he said. The words cost him pride. He had once believed that praise should be rationed, that the world paid you when you earned it. He looked at Leah and understood that certain economies were a sin. “You did good, Leah.”

In the small hours, Dr. Joshi came with the first decent news: a temperature down, oxygenation up, the word stable written on a face that had not planned to offer it. “It is still acute,” she said. “But the antibiotics are taking hold. She needs calories. She needs time. She needs someone to sign consent forms.” The last sentence was for someone like Robert. Or for a system that had not yet noticed the girls when they were freezing, but would notice now that care cost money and signatures.

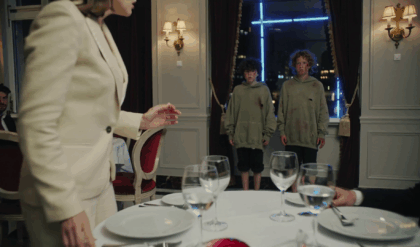

By morning, CPS had noticed. A caseworker younger than some trailers Robert owned arrived with a manilla folder and a vocabulary of statutory phrases. “Temporary protective custody,” she said. “Placement preference with licensed foster families,” she said. “Home study,” she said. Marta Torres, who turned out to be Marsha in conversation despite the badge, stood with her arms crossed and watched Robert as if he were a suspect who had returned to the scene.

Leah had not slept. Robert had slept in the chair with his chin on his chest and woke with guilt that felt like something left on a stove too long. He stood now and spoke with the restraint of a man who had argued Supreme Court cases in conference rooms without judges. “There are families waiting,” Marsha told him. “Years. We can’t create shortcuts.”

“Then don’t,” Robert said. “Create a door.”

“A door?”

“Into which I can walk.” He did not raise his voice. “Do your checks. Interview me. Turn my life inside out. I’ll sign whatever you put in front of me. But don’t take that child somewhere she doesn’t know and call it safety. She had safety last night because she slept while I watched.”

Marsha’s face shifted a degree toward human. “It’s not personal,” she said, and he saw that of course it was personal. Every failure of the system sat on some particular pair of shoulders at three a.m. “We can file for kinship-exception placement under exigent circumstances if the judge—”

“Then ask the judge,” he said.

She looked at Leah, who looked at Robert. “Do you want to be with Mr. Hale?” Marsha asked, and Robert saw how much weight adults like to place on a child’s small back. Leah could have answered anything and he would have made it true. She said, simply, “Yes.”

Paper created a temporary kind of time—a legal air bubble in which a life could travel from one room to another. By afternoon, a hearing was set in Suffolk County Juvenile Court. Robert put on the same suit he wore to funerals and quarterly calls. He took Leah’s hand and they rode in a city car that smelled of winter coats to a building that wore justice like a sour perfume.

In the courtroom, the judge looked over reading glasses with the fatigue of someone who had seen children used as leverage and someone else’s money used as absolution. The CPS attorney recited the phrase families-waiting-years as if it were a ward to keep the rich from doing what the rich do. Robert stood when told, said his name, his address, his business. The attorney said, “The department does not object to emergency temporary placement with Mr. Hale provided conditions are met.” Conditions were recited, written, initialed.

Then the judge looked at Leah. “What do you want, Miss…?”

“Leah,” she whispered.

“What do you want, Leah?”

Leah’s fingers tightened on Robert’s. She lifted her chin with a courage that made the court reporter pause. “To not be alone,” she said. “He didn’t let my sister be alone.”

The judge’s mouth softened into something that might once have been a smile. “Emergency temporary custody to Mr. Hale,” he said. “Review in thirty days.” The gavel did not bang. It was too early for punctuation.

On the sidewalk outside, Boston was still winter-throated. Leah’s plastic backpack thumped against her shoulder. They walked to Robert’s SUV as if leaving a church, quiet, sober with the relief of having survived another hour. In the car, Leah stared straight ahead, then said without looking at him, “If you get tired of me, you can tell me. I’ll go quiet.”

Robert put the car in park again. He could feel his own heart the way you feel a bruise. He turned to her. “Leah,” he said, and he heard Lydia in his mouth—Lydia who had spoken like this when she wanted him to understand something once and for all—“I will not get tired of you.” He waited until she looked at him. “Not ever.”

The Beacon Hill townhouse had been staged for magazine spreads and left like that, a model home into which no actual life had moved. Robert had liked it that way after Lydia—everything clean, as if grief were sticky and could be defeated by Windex. The front hall’s black-and-white marble caught the afternoon light. The living room’s built-ins held books curated by someone in the staging company who believed billionaires read the Stoics.

Leah did not move past the threshold until he said, “This is your house.” Even then, she sidled like a cat and stood in the doorway of each room as if rooms were oceans and doorways were docks. He showed her the bedroom that looked over the garden. Someone had made it guest-neutral with white linens and a vase of fake peonies. He said, “We’ll change it,” and realized the we was what mattered.

There are quiet domestic miracles when a new life enters a space. They are not cinematic. They look like a toothbrush in a glass with another. They look like sneakers by the mudroom bench. They look like drawings magneted to a refrigerator that once held donation receipts with dates. The first miracle in Robert’s house was a crooked crayon picture left on the kitchen island the next morning: three figures holding hands under a lopsided sun. He kept that paper like a contract.

Julia’s improvement was neither straight nor guaranteed. Some days the numbers rose and stayed. Other days they fell without explanation as if they had their own weather. Robert made a schedule nobody asked him to make: morning at the hospital; midday at work where his CFO learned to bring only decisions that could not wait; evening back in the pediatric ward where he learned the names of all the nurses on the night shift and how to silence the IV pump when it beeped mid-bag. He discovered he could sign consent forms without reading them because he trusted Dr. Joshi more than he trusted the part of his brain that insisted on control.

Leah discovered the library on Charles Street where the children’s librarian treated her as if she had always belonged to books. She discovered that hallways in houses echo differently when someone runs through them laughing. She discovered that the house had stairs that felt like mountains and a bathtub deep as a lake and that you can sleep without keeping one ear awake.

One night, after Julia’s blood oxygen held steady for a full day, Leah stood in the bedroom doorway with a blanket folded under her arm like an offering. “Can I ask you something?”

“You can ask me anything,” Robert said, and the surprise was how true it felt to say it.

“Do you think I make too much noise?”

He had spent three years chasing silence as if it were cash. He had measured success by the absence of interruption. The question pried up a floorboard inside him and showed him what lived beneath. He knelt to Leah’s height because knees teach mouths what to say. “This house,” he said, “used to be too quiet. You fixed that.”

She smiled like someone learning a new word she loved, then looked at the bed and back at him. “Can I sleep here? Just until my stomach stops… thinking.”

“Of course.” He had slept for months beside a bed that held no one; the shape of a small human on the other side caused his nervous system to lay down in a way he had forgotten it could. In the morning, he woke to the sound of Leah breathing. It was ordinary; therefore it was holy.

Work tried to reassert its old dominion. The UAE fund called to accelerate due diligence. A board member demanded Robert “get ahead of the narrative” as if a story like this were public relations. Robert did not become a different man overnight; he did not renounce what he had built. But when his assistant said, “They can only do noon,” he said, “Then they can do next Tuesday,” and hung up without explaining. It turned out the world could bear inconvenience.

Marsha—and she became Marsha for good now, a person not a badge—began her visits. She sat in the living room with a clipboard and asked what Leah ate and whether Robert knew the names of her teachers and whether there were firearms in the house. She opened cabinets with a practiced politeness and checked outlet covers. She looked at the refrigerator art and did not look at the whiskey bottles, though they were there: two unopened and one with a finger missing.

“You’re doing… fine,” she said once, as if fine were a surprise. “But I have to ask. Why you?”

Robert could have said what men like him say to make themselves sound good: fate, conscience, the duty of those with much to those with little. He looked at Leah tracing letters at the kitchen table and said the only truth that felt like it didn’t perform. “I was there,” he said. “And I couldn’t not be.” He looked at the drawing taped above the stove: a new one, this one with more details—the garden fence, a dog they did not have but might, Lydia’s peony bushes as Leah imagined them without ever knowing Lydia. “I think I left my life for a while,” he said. “I think maybe I came back.”

There are rituals that make a family visible to itself. The first Saturday they kept Julia home overnight, they made pancakes though neither Robert nor Leah had ever made pancakes; the pan smoked and the first attempt looked like a topographical map of sorrow, but by the third batter the kitchen smelled like something grandmothers would recognize. Leah insisted that the first good pancake go to Julia in small pieces because “she gets the best parts ‘cause she’s little.”

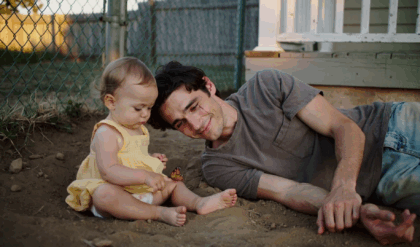

In March, snowfall came soft as a memory and then stopped. Julia learned to point with a small decisive finger at everything she wanted: light, cat (a neighbor’s), up, Leah. Robert learned to lift her without thinking, learned the weight of her asleep face pressed into his shoulder. He learned to drive without thinking to the cemetery on his way home. He drove instead to the playground near the river where the wind smelled like thawing iron.

At work, something else thawed. His engineers—grim with the burden of being the smartest ones—came into meetings less armed. A junior project manager named Cleo put up her hand to say, “If we’re serious about hospital infrastructure, we could do something at cost for MGH’s pediatrics. It would pay us back in ten press releases.” She said it smiling, daring them to accuse her of sentiment. Robert said, “Make it not a PR stunt. Make it a line item that survives the next quarter.” Cleo blinked and then looked down fast as if she had been seen and did not know what to do with it.

A month brought the thirty-day review, which stretched to sixty because courts move like rivers—slow in the shallows, violent in the narrows. The day of the decision, the courtroom had the same gray carpet, the same clock slow by two minutes. The judge asked questions meant to make liars trip. Robert did not trip. Leah wore a yellow dress Marsha had dropped off—“Don’t fight me,” she’d said, “let me do one nice thing”—and held Julia on her hip like a small queen.

“Mr. Hale,” the judge said at last, “do you understand the permanence of this request?”

“I do,” Robert said. The words assembled as if they had been waiting on the other side of grief for years and were glad to be used. “I also understand that permanence is a myth. But I will be permanent in the ways I can.”

The judge did not smile. “Adoption is granted.”

Leah’s hand found his without looking for it. The clerk brought papers like a stack of doorways. Robert signed his name where the arrows told him. He had signed mergers and debt offerings and an op-ed ghostwritten by a crisis communications firm. He had never signed anything that altered the physics of a house like this.

News gets out in ways the news-hungry prefer to call sleuthing. A columnist with a taste for gotcha wrote that a tech billionaire had bought himself a narrative. He wrote it tidy, in a column that sat between a restaurant review and an op-ed about parking meters. Robert read it in the kitchen and tore the page not because of anger but because his hands were not calibrated for what he felt. He discovered he could not be wounded by strangers who had not knelt in a wet alley. He discovered he could be wounded only by Leah losing her courage when she read a headline; so he kept the paper away and told the women at the library to make sure Leah never had to see herself turned into a story that forgot to be careful.

On a warm April night when the city pretended it would never be cold again, Robert took the girls to Fenway because Lydia had loved baseball for reasons that had nothing to do with baseball, and grief’s kindest gift is that it can be smuggled into joy if you’re gentle. They ate hot dogs with too much mustard and Leah learned how to keep score in the old-school way on a program with a tiny pencil. In the seventh, a pop fly arced so high it looked like something reconsidering heaven. Leah looked up with her mouth open, then clapped both hands to her cheeks when a man three rows down caught it one-handed while holding a beer in the other. Julia shrieked at the idea of this magic and the whole section turned to look; strangers smiled like family.

That night, Leah fell asleep in the car seat, and Robert carried her into the house the way he had once carried Lydia’s flowers, careful not to drop a petal. He paused in the hallway, Leah’s breath warm in his neck. The townhouse did not feel staged now. It felt like a place that would be embarrassed to be photographed. There was laundry on a chair and a rubber duck under a lamp and a pair of tiny sneakers on the doormat daring anyone to complain. He wanted to freeze-frame it, not to keep it forever—the trick of grief is wanting stasis—but to thank it properly.

Summer found them. Julia’s chest scarred over where pneumonia had tried to write its name; she learned the exact sequence of buttons to make the musical cow play the song. Leah learned to swim at the YMCA because Robert had grown up on a council estate in Lowell memorizing the price of things and had never learned to push water out of his way like joy. He sat on a metal bench and watched her move through blue like a creature that belonged there. He stayed late and later, saying yes to “Again?” until the lifeguard announced closing with a whistle tuned to regret.

In August, the corporate jet took off without him for a deal he had decided someone else could close. He took Leah school shopping instead. “You don’t have to buy the expensive ones,” she told him shyly, holding a pack of ten-dollar pencils as if they were too much. He had learned not to say, I can. He said, “We’ll get the ones that don’t snap when you sharpen them,” and let the budget land where it needed to.

There were bad days. A fever for Julia that made the past arrive in the room and stand with its arms folded. A nightmare for Leah that made her wake under the bed. The sudden return of a birth mother’s name on a form, a mother who might call and say I am ready now. Robert had hired a lawyer not because he wanted to fight but because he did not want to be naive. He sat with Leah on the back steps and told her, “Your mother will always be your mother. And I will always be your Robert. If both things are true at once, we will live with it.”

“Do I have to call you Dad?” she asked, eyes cautious over the word.

“No,” he said at once. “You have to call me what feels true in your mouth.”

She tried out Robert again as if confirming it still fit. Then, very small: “Sometimes I want to call you Dad.”

“Then do it the days you want to. And the days you don’t, don’t.”

She nodded, relieved to be relieved of the burden of consistency adults place on children as if they were mortgages.

In October, on the anniversary that Robert did not put on a calendar, they drove to the water where Lydia had liked to walk the Harborwalk and throw crusts to gulls who were rude and magnificent. They sat on a bench. Leah did not ask him to talk about Lydia, but she watched his face with a viability he had not offered anyone else since Lydia died. He said, “She laughed at bad jokes and cried at commercials. She believed kindness could be engineered into things if you paid attention to the first ten minutes of a process.” Leah listened as if this were a class she had secretly longed to take.

“What do you believe?” she asked.

“I believe,” he said, and he heard how the verb steadied him, “that sometimes the only thing we control is whether we stay.”

“Like you did in the hospital,” she said.

“Like you did in the alley.”

She shook her head. “I wanted to run,” she said. “But I couldn’t, ‘cause I had to hold the little one.”

He looked out at the water. “Sometimes wanting to run is proof you’re human. Staying is proof you’re brave.”

They went home and made Lydia’s favorite pasta with too much garlic, and the house smelled like someone else’s memory and then became theirs.

The winter that followed was kinder. The rains came as rain, not knives. Leah brought home a science fair flyer and a face that said she was about to ask for the moon. “I want to build something,” she said. “But not one of those volcanoes everyone makes that’s just pretend. I want to build a warm box for people who don’t got houses. And I want to make it cheap so other people can make it too.”

Robert had raised venture rounds on flimsier pitches. He knelt beside the table where she had spread her drawings—ducting, insulation, a battery scavenged from a busted scooter. “We can do better than cheap,” he said. “We can do replicable. And we can write instructions that assume the builder is smart. Because they are.”

They worked evenings with cardboard and foil and the kind of tape hospitals use on the living. He brought home a small fan with a brushless motor and taught Leah the word laminar. She taught him the word cozy as an engineering requirement. They set the finished box in the garden with a thermometer inside and watched the numbers hold. Leah wrote a poster that never once used the word charity and got disqualified from nothing.

At the science fair, a judge asked the ritual question about inspiration. Leah looked him in the face in a way she would not have months ago. “Because warmth is a right,” she said. “Because if you keep someone alive at night, they can do the rest in the morning.” The judge put down his clipboard like a man deciding to be new.

That night, when the girls were asleep, Robert stood in the doorway between kitchen and hall with the lights off and listened. The house had a sound now—the sibilant, ordinary whisper a house makes when it agrees to hold you. He remembered the December lane as if it were a room in the house, a dark pantry where something had been kept and then brought out into the light. He wanted to say thank you to the alley, to the kind of grief that lets joy in through a side door, to whichever arrangement of chance and choice had put him within earshot.

He did not become a saint. He paid the tax bill and argued with the city about a curb cut. He snapped at a board member and apologized badly. He bought a dog because Leah’s drawing had foretold it and then discovered that the dog shed hope as if hope were hair. He retired the umbrella from the day he met the girls and put it in a closet as if it were a banner. He learned the exact sound Leah’s laughter made when Julia did something bossy and small-sisterish, and he filed that sound somewhere better than a bank.

Sometimes, late, when the house had dried its dishes and the dog had decided to sleep across the door like a guard who believed in ritual more than threat, Robert stood in the window and looked at the city. The tower where he had almost said yes to the fund blinked like a lighthouse. Somewhere, some other man who had turned his grief into a measurable thing walked past some other alley and did not stop. It would have been Robert. It might have been. He did not make the city smaller with this knowledge. He did not make it bigger. He let it be what it was: a place where, if you listened, you could sometimes hear one true thing from far away.

When spring returned, they took the train to New York because Leah had never seen buildings that cut the sky open like that. In Bryant Park, they ate sandwiches sitting on cold chairs and watched a wedding party in navy suits chase a veil across the lawn. Leah asked, “If you ever marry again, does that mean Lydia goes away?” He answered the only way that did not insult the dead or the living. “No,” he said. “It means she sits in the front row and claps.” Leah nodded with the calm of someone who could imagine a world like that and decided to live in it for a while.

Julia learned a new word on that trip—“mine”—and applied it to a pigeon, a water bottle, and Leah’s braid. Leah learned the pleasure of letting something be hers while letting someone else touch it. Robert learned how to keep three breaths together when all three wanted to go their own way.

On the anniversary of the court’s adoption order, Marsha came by with a cake from a bakery that misread names in charming ways. HAPPY ADOOPTION DAY, it said, and Leah laughed until she hiccuped. Marsha stayed a while after the cake was cut and watched Leah put two pieces in a container labeled for Mrs. Aziz, the downstairs neighbor who sent up rice when she heard children cry.

“You know,” Marsha said in the hall as she left, “the thing we never ask on forms is how someone plans to stay when it gets boring.”

“We could add a checkbox,” Robert said. “I plan to stay when it gets boring.”

Marsha smiled. “Maybe we should.” She touched the doorframe. “I’ve checked a lot of boxes in houses that never knew what to do with the paper. This one… knows.”

After she was gone, Robert put the girls to bed and stood in the kitchen finishing a slice of the misspelled cake. He thought of forms, of doorways, of the word adopt which means take and also choose and also carry. He thought of the alley and how the city had not noticed their turning. He thought of the first thing he had heard that day—crying—and the last thing he heard now—Leah laughing in her sleep—and how the distance between those sounds was the measure of a life.

He washed the plate. He turned off the light. He went upstairs. The house sighed like a horse in a stall. He opened Leah’s door and saw, in the glow of the hallway lamp, the tangle of braid and blanket and child who was no longer planning to run. He went next to Julia’s room, where a stuffed cow guarded the crib like a knight. He touched two fingers to the small back that rose and fell with unimportant regularity.

“Mine,” Julia said into her dream.

“Yes,” he said softly. “Ours.”

He lay down in the dark beside the life that had unfolded without permission and decided, as if deciding were a posture that could be held like a plank, to listen hard enough that the next true thing couldn’t help but find him. The city murmured around them. The winter he had walked into at the beginning had finished its sentence. New weather was coming, complicated and plain, and he meant to be out in it, umbrella retired, pockets open, ready.