New York had been swallowed by rain the night Alexander Wright stepped from a black limousine on Fifth Avenue and saw the past staring back at him from a piece of cardboard. The sign was wilted, the ink bleeding: PLEASE HELP US. HUNGRY. HOMELESS. The woman holding it was soaked through, hair plastered to her cheeks, arms wrapped around two children who looked nine—maybe ten—shivering beneath a too‑thin hoodie. Neon broke into pieces on the wet sidewalk. Taxis hissed by like yellow fish. The doorman of the glass‑walled hotel lifted an eyebrow at the trio on the curb and then at the man in the tailored coat, the one they called a rainproof billionaire on magazine covers.

Alexander’s stride faltered. He knew that face under the rain and shock and exhaustion. Dark brown eyes with a steady light he had not managed to forget. Isabella Rivera. Ten years earlier, back when he was still sleeping four hours and chasing something he could not name, she’d been a maid at a mid‑tier hotel in Chicago where he’d holed up between deals. One night—one charged, unguarded night—had carved itself into memory like a scratch under varnish. He boarded his plane before sunrise and never saw her again. Life had rushed in with its cranes and closings and glass towers. The empire rose. The scratch stayed.

Now the scratch had become a mirror. The boy’s jawline was his. The girl’s eyes were the same clear blue that showed up in old family photographs. He felt something catch in his chest, like a lift that had glided smoothly a thousand times and suddenly stopped between floors.

“Mr. Wright?” his assistant, Grace, said from behind him, voice gentle but urgent. “Our investors are already upstairs.”

He took off his coat and draped it over the shivering kids before anyone could stop him. The fabric swallowed them like a small tent. Isabella looked up, saw him, and froze. For a beat the thunder of Midtown rain filled the space where words should have gone.

“Isabella,” he said, and the city dropped out of his voice. “What happened?”

Her lips parted. No sound. Then his name, soft as if breathing it hurt. “Alexander.”

By the time they reached the elevator, the doorman was holding the door with both hands and trying not to stare. The twins moved like deer who had learned to run first and trust second. In the suite upstairs, hot air and light and bowls of soup made the night tilt toward human again. Steam fogged the windows. Jacob and Emily—she finally said their names—ate with the reverence of hunger. Alexander stood by the glass, the city blurring into rain and red brake lights, and tried to catch up to a reality that had lapped him twice.

He turned. “Are they mine?” It came out low, unarmored. He had argued billion‑dollar projects with less fear.

Isabella held herself with the stubborn grace he remembered. Her damp hair curled at her temples. “Yes.” She didn’t let her eyes flinch away. “I wanted to tell you. I didn’t know how. Then I lost the hotel job. Then I moved. Then the rent went up. Then the landlord refused to fix the heat. Then the restaurant closed. Then…” Her hands spread a little, as if a life could be a ledger of losses. “I didn’t want to be the woman who derailed the man building skyscrapers.”

He had left without a number the morning after that night, because he had told himself that was cleaner—easier for both of them. Because he was twenty‑nine and ambition sounded like a virtue and distance like discipline. He felt the truth land in his throat and sit there.

“You should have found me,” he said, and hated the past tense the second it left his mouth.

“Would you have listened?” she asked, not unkindly. “Back then?”

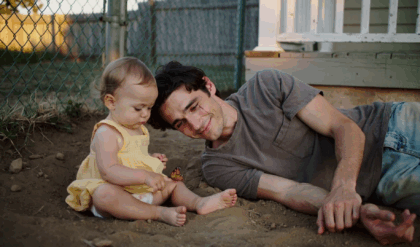

He watched Jacob slide his bowl toward Emily so she could dip another piece of bread. He watched the girl split it in half before she touched it to her lips. Something in his chest that had hardened into a habit began to soften.

“I can’t change ten years,” he said. “But I can change tomorrow.”

By morning the storm had thinned into a cold, clean drizzle. Alexander arranged for a doctor to see the kids—not as a headline, not as pity, but because Jacob had a cough that would not quit and Emily was so thin her wrists looked like question marks. He paid for a suite on the quiet side of the hotel for a week and told Grace to cancel his lunches and the cocktail reception and to book a meeting with the company’s general counsel.

“It’s going to be messy,” Grace said, in that way of hers that meant she’d already mapped out the mess on a mental whiteboard and labeled the axes.

“I know.”

“Messy doesn’t scare me,” she said. “But lies do. Tell the truth early.”

He nodded. The paternity test was a formality, an answer to a question his bones had already answered, but the test was done. Isabella watched the nurse swab Jacob’s cheek and then Emily’s, her hand resting on each head like a benediction. When it was over, she stepped into the hall with Alexander.

“I don’t want your money,” she said.

“You’re getting my time,” he said. “Starting now.”

And then he did something that surprised even himself: he left a board call five minutes before it ended and took the twins to a thrift store in Park Slope where the owner called everyone sweetheart and had a rack of children’s rain boots in the back. He bought toothbrushes and socks and a ridiculous umbrella with sharks on it because Jacob smiled for the first time that day when he opened it and made the Jaws theme with his mouth. He bought groceries that filled a cart for the first time in months, if Isabella’s startled look in the dairy aisle meant what he suspected it did.

On the third day, when the doctor said Jacob’s lungs were fine and Emily’s bloodwork looked good but both could use steadier meals, Alexander took Isabella to see a narrow, sun‑bright townhouse he kept in Cobble Hill for out‑of‑town staff. It had a small brick patio and a maple tree that would burn red in the fall. The place smelled faintly like cedar and fresh paint.

“It’s yours,” he said. “For as long as you want.”

Isabella stood in the front room, her hands pushed into the pockets of a borrowed cardigan. “I don’t want to live on your charity.”

“I don’t want you to live on my street, in the rain.” He met her eyes. “Call it a debt. I owe you a decade.”

Her mouth quirked. “That’s not how debt works.”

“It’s how this one does.”

She didn’t answer for a long moment. The house was quiet around them, the way a new place is before a family’s sounds teach it who it belongs to. He expected refusal. He had underestimated hunger, and not just the kind the twins had answered with soup. “We’ll stay,” she said. “For now.”

He bought beds. The delivery guys wrestled the frames up the narrow stairs while Jacob measured everything with a tape measure and announced numbers like a town crier. Emily placed her new books on her new shelf one at a time, the way a person sets down treasures in a temple. When they realized there was a small patch of soil off the kitchen where something could be planted, the girl pressed her hand to the dirt and whispered something Alexander did not hear.

He stood at the sink with a sponge and realized he had no idea how to assemble a drying rack. He, who could assemble a financing stack in his sleep. He laughed once under his breath, and when Isabella came in carrying a folded stack of towels the laugh caught her ears. She stopped, watched him for a second, and tilted her head as if seeing the contrast did something novel and private inside her.

The tabloids found them in ten days.

BILLIONAIRE’S SECRET FAMILY SPLASHES DOWN IN BROOKLYN. The article used a photograph of Alexander in jeans and an old Columbia sweatshirt—the sort you wear only when you forget who you are for a minute—carrying two bags of groceries in the rain. Another photo caught Isabella through the townhouse window, head bowed over a roll of parchment paper as Emily sprinkled flour like confetti. A third image, grainier, caught Jacob’s face. Alexander called the paper. Grace called the lawyer. The paper did not apologize. He bought blackout curtains and then better ones.

The board called an emergency session.

Victor Ames, a man whose hairline had fled the scene years ago with his sense of proportion, cleared his throat and leaned into the first sentence like a man about to be brave at great inconvenience to himself. “Alexander, I’ll be direct. We support your… personal situation. But perception is tied to valuation, and valuation is our duty to shareholders.”

“Perception has a way of catching up to reality,” Alexander said. “I’m not ashamed of reality.”

“We’re about to bring a three‑billion‑dollar waterfront project out of escrow,” Victor said. “There’s a world in which your… revelations… complicate approvals.”

“Then let’s live in a better world,” Grace said from the back of the room, not bothering to hide that she hadn’t been asked to speak.

Celeste Hemmings, the CFO, sat with her pencil balanced horizontally across both index fingers. “It’s about volatility,” she said quietly, not unsympathetic. “Investors fear what they can’t model.”

“I’m not a black swan,” Alexander said. “I’m a father.” He let the word settle on the table between all their clipped syllables and line‑item nerves. “We build towers that touch light. If the foundation of my own life is cracked, what are we even doing?”

The room did not applaud. But something in the angle of Celeste’s shoulders changed. Victor studied his notes as if they might learn to say something easier if he stared long enough.

After, on the sidewalk outside the glass box where they planned a city like a puzzle, and sometimes remembered the city was full of people who weren’t pieces, Grace walked with Alexander toward the corner. “You always said you’d never apologize for wanting more,” she said. “Maybe it’s time to change what more means.”

He went home and burned pancakes and lied to the kids about it. Emily ate her charcoal crescent and solemnly declared it “camp style.” Jacob asked if camp was where food went to die. Isabella stood at the stove, nudged him aside with her hip, and taught him about medium heat and patience.

Two weeks later the test results came back with a bureaucratic font that undersold their impact. Probability of paternity: > 99.99%. Alexander stared at the number until it blurred and the punctuation looked like constellations. He forwarded the PDF to himself, printed one copy for a folder in his office safe, and then tucked a second copy into an envelope and slid it into the junk drawer in the Cobble Hill kitchen because he knew, with a certainty that surprised him, that he would read it again some night when Jacob and Emily were asleep and doubt came like weather.

Isabella started school at night at CUNY. She picked up a part‑time job at a small property management company in Carroll Gardens after politely but firmly declining Alexander’s offer to set up anything within his web of businesses. “If I earn it standing up, I’ll never have to wonder what I owe,” she said. He hated how much sense that made, and loved her more for saying it.

On Tuesdays, he took Jacob to soccer at Pier 5 in Brooklyn Bridge Park, where the East River looked like steel and the ball skittered toward the water like it had its own opinions. On Wednesdays, Emily had a music club at school, and Alexander sat on a small chair in a big room and forgot there was ever a world where the volume of his presence was measured in square footage.

He learned the names of teachers. He learned that Jacob hated gym but loved taking things apart to see the bone of them. He learned that Emily laughed with her whole face. He learned the schedule of alternate‑side parking on their block, and that if you double‑park on the left on Thursdays your neighbors will try to squeeze by with a hand up in that half‑apology New Yorkers wear like a uniform. He learned the exact angle the afternoon sun fell onto the kitchen table around three, turning the maple leaf outside the window into stained glass.

On a Thursday morning in April, a woman from Child Protective Services came because someone had called. Isabella chilled in the way you chill when a uniformed stranger is asking about your kids and you know how fast strangers can make your life into a file.

“We heard there was a transient living situation,” the woman said, not unkindly, frowning at a clipboard that did not smell like maple leaves. “Change can be hard on children. Can we do a quick home assessment?”

Alexander could feel Isabella’s spine go rigid beside him. “Is this because a billionaire put two kids in a townhouse?” he asked, and instantly regretted the edge in his tone.

“It’s because someone called,” the woman said. “I’m someone.”

They walked through the house. The twins showed her their beds, made with the concentration of people who hope neat corners can solve everything. Emily displayed a neat row of paperbacks. Jacob demonstrated the drawer in which he was engineering something that might one day remember it was a robot. In the kitchen, the caseworker paused at the envelope in the junk drawer that had gotten mixed with pencils and rubber bands. She didn’t open it. She looked at the return address—lab in Midtown—and then at Alexander.

“Do you love them?” she asked quietly.

“Yes,” he said.

“Okay,” she said, and left.

They didn’t talk for a long while after the door clicked shut. Isabella washed a plate that was already clean. Finally she said, “I’ve been watched my whole life.”

“I’m sorry,” he said. “I brought the cameras.”

“You brought the curtains,” she said, glancing at the windows with their blackout panels. “Which is something.”

Summer arrived like a freight train. The waterfront project that Victor cared for like a bonsai made it through the city council by a one‑vote margin after Alexander took a microphone in a public hearing and said words people like him don’t often say into microphones. He talked about inclusionary zoning without euphemisms. He talked about tax abatements that shouldn’t be forever. He talked about setting aside an entire building for workforce housing owned not by his company but by a new nonprofit he would fund and then step away from—the Home Together Initiative. He said affordability shouldn’t be a slogan you paste on a rendering; it should be a floor you build.

When he stepped outside into the heat and noise, a tabloid photographer shouted, “Do your street kids get a unit?” It was meant to draw blood. Alexander turned. “My kids have a home,” he said. “We’re building homes for other people’s kids.”

He took more heat in the boardroom for that than he had for being photographed in a sweatshirt. Celeste wanted numbers. He gave her conservative ones. Victor wanted guarantees. He refused to give them guarantees on things that required faith. Grace wanted him to keep going. He did.

At night, when Jacob snored softly and Emily sprawled half off the bed like a starfish about to make a decision, Alexander lay awake and pictured the lobby of an apartment building he hadn’t yet built, with a row of mailboxes no one would ever have to pry open with a butter knife. He could see the elevator. He could see the bulletin board with flyers for a tutoring program. He could see a plant that kept being watered.

In August he took the twins to Coney Island. They loved everything they were supposed to love—Nathan’s hot dogs, the Cyclone, the boardwalk smell of salt and sugar and roofs roasting in sun. Alexander, who had done St. Barths and Santorini as if collecting experiences could make a life, realized the Cyclone did not care where he kept his money. It shook him exactly like it shook everyone else, and when he stumbled off it with Jacob’s hand in his and Emily laughing so hard she hiccuped, he loved the ride for that.

Isabella gaped at him when he bought the photo the ride snapped at its meanest drop. “That is the least dignified you have ever looked,” she said.

“Then frame it,” he said.

She did. It went on the mantel, next to a picture of the kids in the park wearing matching ridiculous shark umbrellas.

It wasn’t all sweetness. The mess came, as promised. It arrived one Tuesday when Alexander’s past knocked at Isabella’s door with lipstick and lawsuit nails.

Camilla Bennett had been a feature in the lifestyle section more than once, photographed at dinners Alexander had gone to because he’d thought that was what men like him did on Thursday nights. She was lovely and bored, a combination that can make a person dangerous if they decide to pass the time. She showed up with a voice like polished ice and an attorney who handed Isabella a cease‑and‑desist letter claiming “reputational harm via false insinuations.” The letter was nonsense. It was also a threat wrapped in grammar.

“I told nobody a thing about you,” Isabella said, standing with the door half closed, the way you position a shield when you don’t want to escalate.

Camilla flicked a glance over Isabella’s shoulder at the life behind her—the tidy living room, the plant on the sill that Emily had named, the dinosaur Jacob had glued to the lamp because “now it’s a volcano.” “I’m sure,” she said. “You’re so tidy about what you do and don’t ask for.”

Alexander arrived mid‑visit. He took in the tableau, felt his stomach turn, and told Camilla and her attorney to get off the stoop. “If you have business with me, you know where my office is,” he said. “If you have business with Isabella, you don’t.”

Camilla’s smile hardened. “Enjoy your charity. Call me when it bores you.” She went down the steps like a ballerina exiting a stage and left the letter behind, a paper snake.

Isabella watched Alexander pick it up and put it in the recycling. “You brought them here,” she said, not accusing so much as observational, like naming a weather system.

“I’ll keep them there,” he said, meaning away, meaning outside, meaning wherever former lives belong when the current one matters more.

“But you can’t,” she said softly. “Not always. That’s the truth about storms.”

He wanted to tell her he could build a levee tall enough for anything. He wanted to tell her that because when you are used to cranes and cashflow you think you can out‑engineer grief. He didn’t say it. He stood in the doorway and felt the rain he had already invited.

They argued that night for the first time. About loud things that were secretly quiet things. About money, which was never just money. About privacy. About the day Isabella had seen a photo of Alexander on some yacht three years back and turned off the TV and gone to work the lunch shift and told no one that the shot had felt like a door closing on a hallway in her own head.

He slept on the couch. In the morning Emily brought him a blanket and a drawing of a house with four stick figures under a big square of blue.

Fall came. Maple leaves turned flame and then rust. School recommenced its daily march. Isabella took a class in project management and found, to no one’s surprise but her own, that her brain took to Gantt charts like a bird to wind. She started as an assistant at her small firm. By December she was running three small buildings with a firmness that made plumbers call her back and tenants call her kind.

At Thanksgiving, Alexander roasted a turkey that looked like a magazine cover and tasted like a polite handshake. Isabella laughed into her hand over the sink while she rescued the gravy. Jacob engineered a support system out of Lincoln Logs for a pie that had collapsed. Emily made place cards with everyone’s names and a tiny drawing of something the person loved. Isabella’s had a small building on it with a tree out front. Alexander’s had a tower with a kite string coming off the roof, a tiny Emily on the other end, hair flying.

In the lull after pie, when the kids were on the floor making a fort out of chairs and blankets and huge plans, Isabella told Alexander the part she had never told. About the night in that Chicago hotel when she put her hand on his chest and felt how fast his heart went and thought that maybe that was what ambition sounded like inside a person. About learning she was pregnant and thinking it was a blessing and a sentence and sometimes the two were twins. About the manager who told her it was “unprofessional” to come back once she started to show. About the apartment with mice, and the landlord who charged an extra fifty if she wanted the heat turned up past sixty‑two. About the second job. Then the third. About learning which shelters were safer. About how once, in a laundromat in the Bronx, a woman she did not know held Emily so Isabella could take a shower and wept with her afterward without asking a single question, which is a form of respect she had not known she was permitted.

“I am not a tragedy,” she said, looking at him level. “I need you to know that.”

“You’re the bravest person I know,” he said.

“Bravery is what you call it after,” she said. “During, it’s just not dying.”

In January, the Home Together Initiative signed its first deed: a shuttered hotel near Laguardia that would become one hundred and twenty units of transitional family housing, with a daycare on the ground floor and a kitchen where residents could learn to cook for a crowd. Alexander signed the papers and then, hand shaking only a little, signed a separate document: he was stepping back from day‑to‑day CEO duties to become executive chairman. Celeste would be interim CEO. Grace would become COO. Victor would remain Victor.

He told the press that leadership was about knowing when to hand someone else the keys. The market, which at first had flinched like an animal, settled. In the evenings, he read to Emily from a battered copy of “From the Mixed‑Up Files of Mrs. Basil E. Frankweiler,” and Jacob asked him how many gallons of paint it would take to coat an entire building, and he did the math with him at the table, pencil scratching, numbers turning into a bridge they could both walk across.

On a Wednesday that coughed up snow and then changed its mind, Alexander took Jacob to a cardiologist because the boy had mentioned a flutter that didn’t feel like fear. The doctor listened, frowned, ordered an echo. The room went soft. The diagnosis was a minor congenital anomaly with a good prognosis. “Watchful waiting,” the doctor said, a phrase that fit Alexander’s mouth like a stone and then dissolved when Jacob made a joke about how only boring hearts behaved.

Alexander cried in the elevator, quietly, the way men who have been told stories about themselves cry when none of the stories prepare them for an elevator.

Isabella took his hand that night and didn’t let go even when the kettle screamed. “We don’t win by outrunning the bad,” she said. “We win by standing together when it shows up.”

“Where did you learn to be wise?” he asked.

“Laundry rooms,” she said.

Spring rolled in on a wave of soft light. The new building in Queens had a name now—Rivera House, because Alexander had insisted and Isabella had argued and then smiled. A plaque in the lobby read: “A home is not a favor. It is a foundation.” Alexander gave a speech that was shorter than anyone expected and better for it. He pointed to the daycare and said, “That’s hope you can schedule,” and people laughed and then clapped and then, afterward, they stayed a little while in the lobby because leaving felt like undoing something.

At the opening, a woman Alexander had never met whispered to Isabella, “I was you once.” Isabella hugged her the way you hug someone who is exactly your height and had traveled the same road.

As he watched them, Alexander understood something that should have been obvious sooner: Isabella didn’t need rescuing. She needed room. He had plenty of room. He could give it without making the gift a monument to himself.

That night, back in Cobble Hill, Emily fell asleep on the couch with her head on Isabella’s lap. Jacob sat at the table drawing a version of the Queens building where the robot he was building would operate the elevator. Alexander looked at the three of them—light on hair and paper and the corner of a blanket—and felt the particular gratitude that makes promises inside a person.

“I’ve been waiting to ask you something,” he said.

Isabella’s eyes flicked up. “Ask.”

“Move in with me,” he said, and then, because the old habits of a man who plans for contingencies die hard, “Or I move in here. Or we buy the noisy floor above us. Or we—”

She put a finger to his lips. “We don’t need more floors,” she said. “We need the same floor.”

They did not move to his Fifth Avenue penthouse with the view that made people talk about horizon lines at parties. They stayed in Cobble Hill, where the view was brick and sky and somebody’s laundry steaming on a line in winter. He traded a doorman for a neighbor who shoveled half the stoop and expected him to do the other half, and he liked the trade.

They still fought sometimes. He put too much garlic in things. She worried he gave too much of himself away for people who would never send a thank‑you note. He worried she gave too little credit to the fact that some people mailed the thanks without a stamp because they didn’t have one. They were learning each other’s holy stubbornness.

On the tenth anniversary of the night he left her sleeping in a hotel in Chicago, they stood under a cheap umbrella in a warm June rain outside the very hotel where he’d first seen her again, soaked and holding the twins. The city had rearranged the street furniture and painted a bike lane, but the rain hit the pavement with the same applause.

“Do you ever think about how close we came to never seeing each other again?” he asked.

Isabella tilted her face to the sky. “Every day. Then I think about how we did.”

A woman with a stroller paused near them. She was young and looked older, the way too many nights do math on a face. She fished in her handbag and came up with nothing. The baby in the stroller fussed, tiny fists conducting a small orchestra of need. The woman’s eyes flickered to the hotel awning and then away, the calculation quick and brutal: where would she be welcome now?

Alexander stepped toward her and saw the way she recoiled, polite and terrified. Isabella stepped closer too, slower, hands visible.

“We don’t have much,” the woman said before they could speak, chin up in reflexive pride.

“You have enough,” Isabella said. “And you can have a little of ours.” She held out a card with the address for Rivera House and the name of a caseworker who answered her phone. “This place will help tonight. Tomorrow, if you want, I’ll help you find the next place.”

The woman took the card like it might bite. Then she looked at Isabella’s face and something inside her, something like a sigh that had been waiting months to be exhaled, let go. “Thank you,” she said, so quietly the word almost kept the rain off.

They watched her go. When the stroller’s wheels hit a seam in the sidewalk, Alexander stepped forward, lifted the front two inches, set it down gently. The woman didn’t turn. She didn’t need to. The city held the moment the way it holds everything—briefly, completely, and then forever.

“Do you want to come in?” Isabella asked, nodding toward the hotel. “For old time’s sake?”

“Only if we leave quickly,” he said. “Before the lobby tries to make me someone I’m not anymore.”

They went in and dried their faces and ordered two hot chocolates at the bar where men negotiated itches they called deals. They drank them and did not talk about money. Or they did, but in the way that matters: what it buys when you’ve learned what to buy. Time. Stability. The chance to sit together in a storm and not be afraid of getting home.

On the way out, they passed a framed photo on the wall—a charity gala from years earlier. Alexander recognized half the faces. He recognized his own with a shock. He had been smiling like someone performing contentment. Isabella squeezed his hand once, quick and firm. In the taxi, he put his head back and closed his eyes and opened them again when Emily texted a picture of the cat asleep in the salad bowl and Jacob replied with a schematic of how he planned to build a salad bowl that rejected cats.

The ending, when it came, was not a flourish. It was a Tuesday. It began with a note in a lunchbox and a traffic jam on the BQE and a call from Grace that lasted forty‑two seconds and rerouted a board vote. It included a burnt grilled cheese and a math worksheet corrected with a triumphant exclamation point. It included a FaceTime with a women’s shelter director in Newark who wanted to replicate Rivera House and a promise from Alexander to drive over on Saturday. It included an argument about nothing that was about fatigue that was resolved with a nap.

That evening, the four of them walked to the corner deli for milk and came home with milk and raspberries and a plant Emily insisted would be sad if left behind. On the stoop, a neighbor named Sal waved and asked if Alexander planned to join the block association meeting on Thursday because the compost bins were becoming a scandal. Isabella said of course he would. Alexander said of course he would. Jacob said composting was how the earth did magic with trash. Emily said she would make name tags for everyone.

Later, after dishes and a robot autopsy and a piano track that sounded like rain making a decision, they climbed the narrow stairs to the small upstairs room where the four of them fit fine. The city sighed outside their windows. The maple tree lifted its leaves to whatever wind there was. Alexander tucked the blanket around Emily’s feet and set a glass of water on Jacob’s nightstand and stood in the doorway for a moment the way fathers have always stood in doorways, astonished at the size of small lives.

He looked at Isabella. She looked back. No speech. No ceremony. A nod. A life.

The next day there would be other decisions and other storms. The day after that there would be a ribbon to cut in Newark and a third‑grade science fair and a budget meeting where Victor would sigh through his nose as if exhaling might balance a ledger. There would be letters to answer and a plant to water and a person at a bus stop who would need directions and get more than that. There would be the work of keeping what they had built together standing, not because it was fragile, but because all good things require tending.

And there would be rain. It would fall on Fifth Avenue and Cobble Hill and Queens and the roof of a building where a plaque insisted that a home was not a favor but a foundation. It would fall on the shoulders of a man who had built towers and learned to love rooms. It would fall on the face of a woman who had been watched all her life and then seen. It would fall on two children who had learned what forever sounded like when a father said it and then did it.

The ending was that there was no ending. There was dinner tomorrow, and the next day. There was a life, not untouchable to storms, but unafraid of them. There was a door that opened from the inside. There was a family walking through it together, into whatever weather came.