The wrought‑iron gates looked like they had been welded together to keep the world out and the silence in. Behind them, a Belle Haven mansion sat inside its perfectly trimmed hedges in Greenwich, Connecticut—stone bright as a museum, windows tall enough to make a boy feel small. But in the room at the end of the north hallway, where the air conditioner thrummed and the winter draft snuck through a warped sash, an eight‑year‑old woke up curled around a soft, matted teddy bear as if the thing had a heartbeat.

His name was Lucas Ellison. His left leg trembled when he put weight on it, an old injury that made stairs feel like cliffs and hallways like miles. He had been four when a viral inflammation grazed his nerves and left its fingerprint in him. Doctors said children were resilient. Lucas believed them because believing was easier than the other thing.

On mornings when the house smelled like butter and money, he listened to the rhythm of the place to decide who he was allowed to be. Downstairs, a coffee machine started its low rumble, and soon the click‑clack of heels cut through the quiet like a gavel hitting marble. Bianca Ellison—his stepmother since the spring—moved like she owned the earth the house stood on. Beside her, a glossier, smaller echo trailed along in pink slippers: Lara, Bianca’s ten‑year‑old daughter who had inherited her mother’s smirk and the talent for making a room feel like a mirror you did not want to stand in front of.

Lucas lay still and watched sunlight crawl across the wall like a slow spill. He told himself to try the stairs carefully today. He told himself he would ask politely for breakfast, and that the asking mattered. He rolled to sit, set his blue forearm crutch against the mattress, and pulled the teddy—Scout—into the crook of his arm the way he had the night his father left for New York three days ago. Mark Ellison had knelt in that doorway then and pressed a note into Lucas’s palm. Be brave for me, champ. Back before you miss me. Mark had kissed his hair and promised the trip would be quick.

Quick, Lucas had learned, was a word adults used the way weather used clouds—sometimes they stayed longer than anyone wanted.

The kitchen glowed like a magazine spread, gold light splashed across a waterfall island, croissants lacquered to perfection on a white tray next to a glass dome of strawberries. Bianca checked her lipstick in the reflection of the stainless fridge. Lara flipped a glossy lifestyle magazine with a finger that had never scrubbed a pan.

Lucas came down slow, crutch clicking against oak. He kept his eyes on the floor because looking up was sometimes taken as audacity. “Good morning,” he said, because habits were little prayers. “Could I have some coffee? Or maybe a croissant?”

Bianca turned as if she had been waiting to turn. She had the kind of beauty that made strangers lean in and family lean out. “Do you think bread grows in refrigerators?” she asked, laughter already climbing into her throat, eyes not quite finding him. “Didn’t I tell you not to bother me in the mornings?”

Lara didn’t look up. “Mom, he wants our bread,” she said, the our doing the work of three sentences.

“Of course he does.” Bianca brushed a perfect curl behind her ear and touched her daughter’s shoulder with a softness that belonged to someone else. “Boys like that need to learn their place.”

Lucas nodded as if something had been explained. He turned back toward the stairs, Scout tucked under his elbow. The coffee smell followed him the way a song follows you out of a store. He didn’t cry because crying suggested a world where someone would notice the crying. He saved his tears for the dark.

It should have been an ordinary, ignorable morning, the kind you stack and call a childhood. But just before noon, a plate shattered in the kitchen, and silence yanked tight around the sound like a noose.

Lucas, halfway down the hall with his crutch and a book he wasn’t supposed to read at the table, winced. He knew the script before he saw the scene. Bianca stood with her arms crossed, the marble counter sweating a slip of orange juice that spread like a small sun. Lara leaned against the island, eyes bright with a kind of attention Lucas never wanted.

“It was you,” Bianca said, each word placed like a heel on a stair.

“I haven’t even—” The words left his throat strangled. He glanced at the plate shards, at the juice, at his own shoes. He wanted to explain how wanting breakfast did not equal breaking it.

“I saw him, Mom,” Lara said, and the lie slid through the room as easy as breath on glass. “He knocked it over and ran.”

Bianca came closer, each step a metronome. She did not raise her voice. She didn’t have to. “Enough, Lucas. You will not stay in this house and drag our name through pity. Your father has more important things to do than babysit an ungrateful—” She left the last word hanging like something heavy swung from a rope.

Lucas held the crutch tight. “I don’t have anywhere to—”

“Go,” she said, and the syllable snapped.

He tried to stand straighter, to make his spine say what his mouth couldn’t. Bianca’s hand landed on his shoulder, not hard but sure, and when she pushed, the crutch skidded and clanged against the tile. Pain sparked up his leg, bright and stupid. He bit it back because pain had never helped him convince anyone of anything.

“Take your things,” Bianca said. “If you’re not gone in ten minutes, I will call someone who will see you out.”

Lara’s smile tensed. This was the part of the show she liked least—the part where something real nudged the script—but she said nothing. Real had a smell you couldn’t shake once it touched you.

In his room, Lucas slid his small backpack across the bedspread and folded his father’s note like it was currency. He put in a T‑shirt and socks, the notebook where he drew maps of places he had never been, and Scout, who had a scar across his stitched stomach where a seam had split and been mended with blue thread.

At the front door, the light off the foyer chandelier made the floor too polished to trust. He looked back once because boys look back even when they’ve been told not to, and he whispered, “Bye, Dad,” and it came out like the last breath of a balloon.

The gates sighed open at the touch of a button, and the December air washed the warmth off him. The road ran past lawns so clean they looked like photographs, past hedges cut square as a banker’s jaw. He kept to the sidewalk because the curb made a shelf for his fear. The houses wore their lights the way people wear smiles in photographs—confident, practiced, not always attached to anything underneath.

Across the street, a woman paused on her porch with a shawl drawn close around her shoulders. Celia Hart had been a widow for eight years and in this neighborhood for forty. She knew the sound of a gate that meant trouble. She watched the boy with the blue crutch and the too‑thin jacket and felt something ancient in her chest reach forward.

She wanted to call out to him. Instead she watched, because sometimes calling out scares people further away and sometimes watching is how you find the courage to move. By the time she stepped off her porch, the boy had rounded the corner toward town.

The cold had edge to it in the late afternoon, and by early evening it had teeth. Lucas walked until his breath burned and the rhythm of his crutch on pavement felt like a heartbeat he could at least control. Downtown Greenwich held its holiday lights, strings of white draped on bare branches and looped across storefronts. People hurried with bags that looked heavier than they were. A boy with a skateboard laughed into the night and the laugh clipped right through Lucas.

When you are small and alone, the world arranges itself into obstacles. A bench is a throne if you’re brave and a cliff if you’re not. Lucas made a throne out of a bus stop overhang, knees pulled to his chest, Scout pressed to his ribs. Hunger wove its way through him like ivy. Time blurred until it felt like a window that did not open.

A group of older kids clattered by, voices big because group voices can afford to be. One boy slowed and looked at the teddy bear. “You carrying your doll to college, little man?” he said, and the others laughed because laughs rush to fill the space where meanness invites them.

Lucas kept his eyes on the ground. When the boy’s hand darted toward Scout, Lucas’s body moved faster than it had a right to. “It’s mine,” he snapped, voice too loud for his chest. Something in his face—his readiness to lose and fight anyway—made the boy step back. The group moved on, their laughter unfastened now from anything that mattered.

A yellow cone of light jittered across the sidewalk. “Lucas,” a careful voice said. “Sweetheart?”

He tensed, then recognized the silhouette behind the flashlight beam—the shawl, the sensible shoes. “Are you going to hit me?” It surprised him that the question came out of him. He had not meant to say it out loud where it could do damage.

“No one is going to touch you while I’m standing here,” Celia Hart said. She knelt, ignoring cold soaking through her stockings. She slipped the shawl off her shoulders and wrapped it around him. “You’re freezing. Come on now. Let’s get you warm.”

He didn’t answer because he had run out of answers. He let her help him up. Her hand was soft but not weak, the way old oak is. He leaned into it a little and then more.

Celia’s house sat back from the street, a square of light inside a frame of dark. The living room had freshwater‑pearl paint that had seen too many winters, and books stacked into small towers near the heater. The place smelled like coffee even when no coffee was brewing. Celia set him at her kitchen table and slid a plate with half a cinnamon‑raisin bagel toward him, butter glistening like a small apology.

He ate a bite, then another, and then he cried before he knew he was crying. Celia stood by without making the moment smaller with words. When he finished, she wrapped his hands around a warm mug. “When was the last time you ate?”

He squinted as if the answer might be written on the far wall. “Before my dad left,” he said.

Celia put a hand over her heart. “All right. Well, we’re going to fix that. And then we’re going to call your father.”

He looked at the floor. “Please don’t call her.”

“I’m not calling her,” Celia said. “I’m calling him.”

In the great bright house with the iron gates, Mark Ellison let himself in just after nine. The car service had dropped him at the curb because the driver knew better than to crunch over Bianca’s immaculate gravel. The foyer smelled faintly of limes and lemon cleaner, like a restaurant caught between seatings. “Bianca? Lucas?” he called, and the house handed him his voice back, empty.

Halfway up the stairs, a flash of blue stopped him—Lucas’s crutch, splayed across the landing like a fallen flag. Mark lifted it, the aluminum cold and accusatory.

Bianca appeared at the top of the staircase in a silk robe, wine glass catching light like a prism. “You’re early,” she said, smiling in a way that didn’t involve her eyes. “I wasn’t expecting—”

“Where is he?” Mark held up the crutch like evidence.

Bianca set the glass on the banister and folded her arms. “He ran away,” she said, and the words sounded well rehearsed, warmed in her mouth before he even came home. “I couldn’t stop him.”

“Ran,” Mark repeated. “My kid who needs a ten‑minute head start for three flights of stairs? He ran?” He moved past her into the hallway as if maybe the boy were an optical trick that would appear if Mark could just find the right angle.

“Don’t be dramatic,” Bianca said. “You’ve always been too protective of that boy. He made a mess in the kitchen and when I asked him to clean it, he—”

“Stop,” Mark said, his voice suddenly too large for the hallway. The past three days telescoped into a single point: the note he’d written in a hotel room, the calls Bianca didn’t answer, the way a father learns to feel his child across distance like weather. “If something happened to my son—”

Bianca’s expression hardened, her beauty turning to glass. “I am not a babysitter for sick children,” she said. “I am a wife. You said you wanted a life that looked like something. Well, this is what it looks like. Not—” She flicked her hand toward the stair, toward the crutch, toward everything that did not fit a photograph.

Mark’s breath left him, and when it came back, it carried a lifetime’s worth of words he had not said. “That boy is my life,” he said. “Where is he?”

Her silence landed like a verdict. She turned away first. The wineglass, knocked by her elbow, tipped and fell, a comet of red shattering against the floor.

Mark left her with the mess. He carried the blue crutch to the car and drove without remembering the road. He scanned sidewalks and bus stops, his chest tight enough to cut his breath into pieces. He called numbers he had never saved, old coaches and neighbors, the front desk at the pediatrician where a receptionist who had never met him said, “Sir, are you all right?” He did not answer because he wasn’t.

Celia Hart answered on the second ring. “He’s here,” she said, voice steady over the crackle of age and worry. “He’s safe.”

The breath Mark took then shook the car. “Text me your address,” he said, and the words stained themselves with tears he didn’t have time to be embarrassed about.

Fifteen minutes later, he stepped into Celia’s living room and became a different man. The one who had been haggling with suppliers in midtown that afternoon, who had made his case to a boardroom where a view of the city was supposed to substitute for conscience—that man went out the door and didn’t come back.

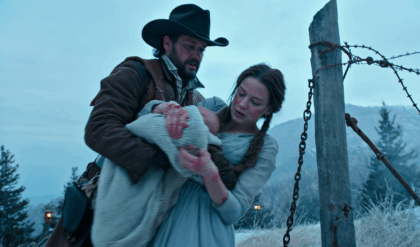

In the small bedroom off the hall, a lamp made a pool of soft light. Lucas lay there on a faded quilt with small blue flowers printed along its border, Scout wedged against his ribs, cheeks smudged with the day. Mark went to his knees the way a healthy person almost never does inside their own life.

“Hey, champ,” he said, and everything in him tore when the boy startled awake and then looked like someone who had been given water.

“Dad,” Lucas said. He pushed himself up, arms straining, and Mark was there before he could fall. The boy’s fingers locked behind his father’s neck. It wasn’t a hug so much as a climb back into a world that made sense.

“I’m here,” Mark said into his hair. “I’m here. I’m not going anywhere.” He would have promised more if promises hadn’t already been cheapened by the way he had used them.

Celia watched from the doorway until her eyes blurred. She backed away and busied herself with the kettle because an old woman’s job is sometimes to give privacy to a miracle.

“Does it hurt?” Mark asked later, eyes on the small bruises along Lucas’s upper arm.

Lucas shook his head, then nodded, then looked away. “She said you didn’t want me,” he whispered. “She said you’d be happier.”

Mark closed his eyes. Words do damage. They also try to repair it. He touched Lucas’s cheek with his thumb the way he used to when Lucas was feverish. “You are my happiness,” he said. “You are the reason any of the rest of it matters.”

Lucas fell asleep with his hand still stuck to Mark’s sleeve. Mark did not move. When he did, hours later, it was only to ease the boy’s hand back onto Scout’s soft belly and to tuck the quilt under his chin. In the kitchen, Celia poured tea into two mugs and slid one across the table. “He’ll need more than tonight,” she said quietly. “But tonight is a start.”

“I left him,” Mark said, eyes on the steam. “I told myself it was three days. That it was business. That there would be more time later.”

Celia’s voice was gentle but contained steel. “The only thing worse than a mistake is pretending you didn’t make one.”

At sunrise, Mark carried Lucas to the car, Scout under the boy’s chin, the blue crutch resting on the backseat like a second passenger. He thanked Celia with a grip that meant as much as the words. “You saved him,” he said.

“I opened my door,” Celia said. “You do the saving.”

The mansion looked different in the early light, less like a magazine and more like what it was: a building designed to impress people who didn’t live in it. Bianca waited in the kitchen with a face reset and a speech prepared. She started to say it and then saw Lucas in Mark’s arms and shut her mouth. Some truths arrive in a room and erase others entirely.

“We’re done,” Mark said. “Pack what you need and leave. If you won’t, I’ll have security help you choose.”

“This is my home,” Bianca snapped, and for the first time her voice slipped.

“This is a house,” Mark said. “Home is where my son sleeps.”

He did not argue further because argument would have honored a version of the last twenty‑four hours that did not deserve honor. He called his attorney and then Child Protective Services, his voice low and even while Lucas ate eggs at the counter and Scout watched with his permanent stitched smile. Mark told the truth. He did not sand its edges to make it friendlier.

The next days were not cinematic. No orchestra swelled to mark progress. Progress was a bowl of oatmeal with cut banana instead of a croissant photographed for other people. It was a pair of hands washing a cereal bowl in the sink and not leaving it for a housekeeper who had always quietly known more than anyone paid attention to. It was Mark buying a slow cooker and a step stool for the bathroom and a handful of stickers that said WAY TO GO because effort, not outcomes, would be the currency in this house.

Bianca moved into a condo on the river with a view designed to convince a person their life was as clean as glass. Her attorney sent letters. Mark’s attorney sent replies heavier than letters. Celia came in the afternoons with grocery bags and stories about her late husband’s impossible roses. When she laughed, Lucas felt the room change shape.

Mark sat at the table with spreadsheets he had once moved through like a knife and stared at them as if they had learned a new language while he was away. He told his partners he would not be in the office for a while. When one of them said, “Is everything okay?” he said, “It will be,” and hung up before the conversation could be about earnings.

Winter leaned hard into Connecticut. On Tuesdays and Thursdays, Mark drove Lucas to physical therapy at a small clinic near the high school where a woman named Maya Chen taught Lucas to love muscles he had learned to mistrust. “Steady,” she would say, tapping his calf. “Let your hip do the work your knee wants to volunteer for. We’re a team. We delegate.” Lucas grinned because no one had ever talked to his body like it was made of interlocking jobs that could be learned.

At night, they read on the sofa under a navy blanket Celia had knit when the TV news made the house feel larger than it needed to be. Mark relearned the art of voices: pirate, professor, dragon. He discovered that making a boy laugh right before bed rearranges a man’s heart.

On Saturdays, they drove down to the water where gulls argued over nothing and everything. Lucas liked the pier because he could sit on the bench and feel like he was part of the river’s decision to go somewhere. Mark put a thermos of hot chocolate between them and listened to his son narrate boats as if he were announcing players before a game. There was a tug with a ribbon of rust along its flank; there was a sailboat so white it seemed to invent its own light; there was a rower in a skull cutting the river into four easy lines.

Sometimes Lucas was quiet for long stretches and then said a sentence that had been building in him for days. “Did you know Scout isn’t scared of the dark anymore?” he said once without looking over.

“That’s big for Scout,” Mark said seriously. “What changed?”

“He knows he can ask me to hold him,” Lucas said. He sipped hot chocolate and pressed the lid back into place carefully, the way he did most things now that he understood care had weight and direction.

A month after the night of the crutch on the stairs, Mark walked through the bright house with a contractor and pointed to the portraits that would come down. He did not want oil paintings of ancestors staring at Lucas as if the boy were a visitor inside his own life. He did not want the echoing dining room that made a child’s voice sound small. He wanted a home scaled to hope and to Scout and to Maya’s charts with checkmarks that looked like small victories lined up in rows.

They moved to a smaller shingled Colonial near the river, a place with floors that creaked in a friendly way and a kitchen that got evening light like a blessing. On moving day, Celia stood at the counter and cried without hiding it. “This house is going to remember you,” she said to Lucas. “Houses do that. They remember the people who teach them what they’re for.”

That first night, Mark tucked Lucas in and the boy reached out and took his father’s wrist. “Don’t go,” he said. The words didn’t accuse anymore. They asked.

“I won’t,” Mark said. He took the floor beside the bed with a pillow and a blanket and fell asleep there with the kind of fatigue that doesn’t hurt because it belongs to work that matters.

The legal parts took their time the way winter takes its time surrendering. CPS completed their investigation. Bianca’s lawyer suggested a settlement. There were hearings where Mark wore a suit and told the truth again in a room where truth had to fit into boxes built by people who had never met his son. There were signatures. There were payments. There was finally the paper that said, in jargon too careful to carry the weight of the thing, that Lucas would not be in Bianca’s care again.

Spring came, and with it a softness to the wind that made the river lean differently. Lucas tried the pool again at the Y. Water had always scared him—too much space to fall in without hitting anything—but Maya was there, and Mark was there, and Scout sat on a towel folded like a throne watching. “Let your breath be bigger than the water,” Maya said. “Bigger than your fear.” Lucas did, and the miracle was small and wet and perfect: three strokes, then five, then a laugh so sudden it surprised his mouth.

They celebrated with diner pancakes the size of a steering wheel. Lucas cut his into eighths because fractions felt like power—eight is more than one, but it is also one if you understand it correctly. Mark watched him and thought of every meeting in which he had argued for margin and realized none of it had prepared him to measure the thing he felt now. There are math problems whose answers are other people’s faces.

In May, Mark stood in the doorway of Lucas’s room and watched his son sleep without the furrow between his eyebrows that had been there all winter. Scout lay on his back like a hero after a battle. On the dresser sat a drawing of the river with a boat labeled OURS even though they did not own a boat. Owning wasn’t the point.

Mark went downstairs and made coffee in a machine that did not hum like a spaceship. He was learning the quiet of good machines and the racket of bad habits leaving. He sometimes wrote emails to his old life and never sent them—long drafts where he explained how he had not understood that childhood is not a season you survive but a place you build so a person can stand inside themselves later.

One morning in June, they went back to the old neighborhood to pick up a box of books Celia had kept for them. The iron gates were still there, bright and tall and ornamental like armor. The mansion glittered. Bianca’s car was gone, her name now a file in a drawer at a law office. Lucas looked at the gates and then at his father.

“We don’t live there,” he said, not as a question.

“We don’t,” Mark said. “We live where you and Scout are.”

Celia met them at the curb with a bag of chocolate chip cookies still cooling on a wire rack. She leaned down to Lucas and said, “What do we say to a house that forgot how to listen?”

“Goodbye,” Lucas said. He smiled like he was setting down a bag at the end of a long road.

They drove home with the windows down and the river moving beside them like a friendly animal. In the backseat, Lucas fell asleep with crumbs on his shirt, Scout under his chin, the blue crutch on the floor where it always rode now—present, useful, not in charge.

That evening, Mark called Maya and told her about the three strokes that had felt like a hundred. He called Celia to ask if she’d come over Sunday for spaghetti because family grows where you put chairs. He stood in the kitchen and looked at the tiny smear of red sauce on the counter and didn’t wipe it right away because mess isn’t always failure. Sometimes it’s evidence.

Before bed, Lucas asked for the story about the night with the flashlight. Mark told it again as if they were looking at the constellations of their life through a telescope that made everything both close and bearable—the gates and the cold and Celia’s shawl and the way a note in a pocket can be a bridge across a river you can’t see the other side of until you’re halfway over.

“Do you still have the note?” Lucas asked.

Mark took it from his wallet, where it had made a home, the crease wearing thin from being unfolded and refolded. He handed it to his son.

“Be brave for me, champ,” Lucas read, his voice not small anymore. “Back before you miss me.” He looked up. “You were wrong.”

“I know,” Mark said. “But we’re here.”

Lucas slid the note under Scout’s paw like a secret kept by a better guard than any gate. He lay back, and Mark sat on the floor again because habits can be prayers the second time, too. They listened to the house breathe with them, the boards settling into the idea that they would belong to someone who asked for less and meant more.

Outside, the river murmured its endless story about getting where you’re going. Inside, the light from the hall made a soft bar against the rug, and in that rectangle, a blue crutch leaned, steady, ready, not the enemy he and it had once been to each other. Lucas rolled toward the wall and slept like a boy who had learned the difference between quiet that hides you and quiet that holds you. Mark watched the slow rise and fall of his son’s shoulders and counted blessings instead of margins, and when he finally lay down, he did not dream of boardrooms studded with glass. He dreamed of water and of a small hand reaching up and finding his.

The house learned their names, and they learned its sounds—the heater’s first throat‑clearing cough in November, the way rain liked the east windows best, the neighbor’s dog that barked at everything except the new boy next door. In the yard, Lucas walked the flagstone path with his crutch and then with less crutch and then with only his hand brushing the hedge as a courtesy. He grew into a body that did not apologize for how it moved. He grew into a voice that could say, plainly, “I’m hungry,” and expect an answer that did not ask him to earn his share of the morning.

Years later, people would point to this time and say that was when everything changed. They would be wrong in the way people are when they try to make a single door out of a hallway of choices. Everything changed in hundreds of small rooms without chandeliers. It changed in the space between a boy and a bear and a father and a neighbor and a cup of coffee and a pool and a river and a room where a blue crutch leaned, harmless as the truth.

And if anyone asked Lucas when he first understood wealth, he would not point to a gate that cost more than some people’s houses. He would tell them about a night when the world had sharp edges, and a woman he barely knew put a shawl around his shoulders and called him sweetheart, and his father knelt by a bed in a room with a faded quilt and said I’m here and made it true.