The wind ran like a wounded animal along the high ridges of the Snowhorn Mountains, a long, throat‑cut howl that lifted powder and worry in equal measure. Silas Granger reined in at the timberline when a smaller sound, thin and sharp as a splinter, caught in his ear. It wasn’t the wind. It was a baby. Then another. Then, God help him, a third.

He swung down into snow that swallowed his boots to the ankle and led his mare by the reins through a stand of black spruce that shook with frost. The path had not been ridden in days; it cut the hillside like an old scar. He moved as men move when time is an enemy—sure, spare, silent—guided more by instinct than sight. The crying came again, a high keening at the edge of failing.

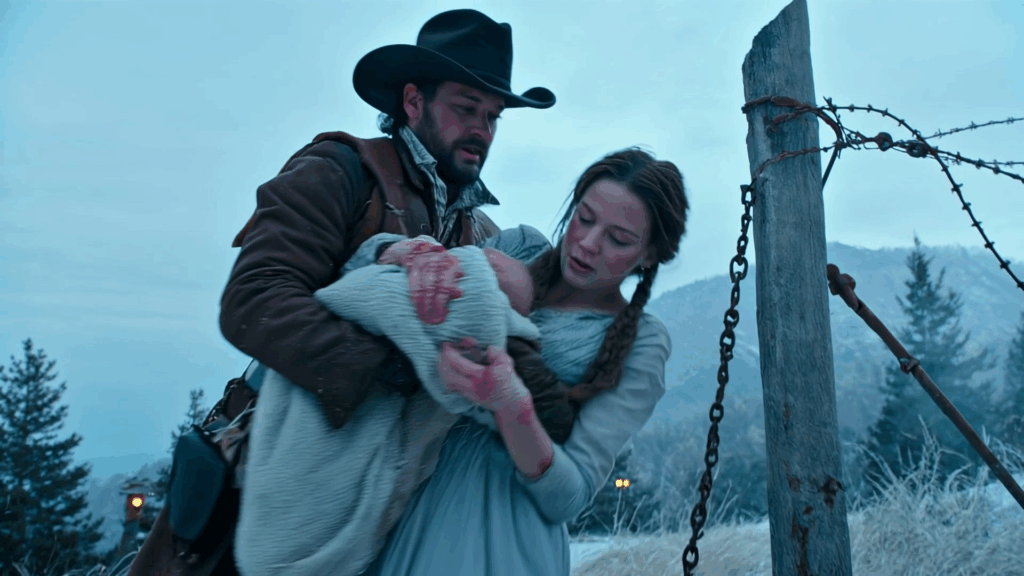

They were in a clearing near a fence post so old the grain had turned gray as bone. A woman leaned against it, half standing because the barbed wire would not let her fall. It bit her wrists and forearms, had chewed through skin and into sinew—rust dark against winter‑white flesh. Snow clung to her lashes. The ends of her hair were glassed with ice. At her feet, three small bundles lay in a huddle of torn cotton and the remnants of a nightgown, faces no bigger than his palm. One whimpered. Two were too quiet.

Silas didn’t ask who. He did not ask anything. He went to his knee in the snow and pressed two fingers to the infant’s neck. Breath. Weak but there. He checked the next. And the next. Then he worked the knife from his boot and slid steel between rusted barbs, cutting her free in three strokes. She swayed when the wire let go. He caught her under the shoulders. She weighed next to nothing.

“You’re coming with me,” he said, voice low and certain, as if assurance could be heat. The woman’s eyes found his. Cracked lips moved around a whisper. “Don’t let them take my daughters.”

He didn’t plan on it.

He lifted her—light and limp as a child—then gathered the babies, one by one, into the thick wool blanket he pulled from the saddle. He tucked the smallest inside his coat where his own body heat might try its hand at mercy. The mare stamped and tossed her head, anxious at the scent of blood and storm. “Easy,” he told her. “We’re not dying out here.” To the animal. To the woman. To himself. To anyone listening.

The climb back to the cabin was half a mile and all uphill, through drifts and wind that swung in hard from the west. He moved without stopping, breathing through clenched teeth as the cold sealed the edges of his beard. The door went in under his shoulder. He carried the woman to the bed of quilts near the hearth and laid her there with a steadiness he didn’t feel. Then the babies, tucked in a basket lined with rabbit pelts, set close enough to hear the fire talk.

The room had four walls, a slant roof, and a stove that grumbled like an old man when the first pine kindling caught. Silas stoked it to a proper blaze and set an iron pot to warm. Behind split wood he kept a jug of goat’s milk against a hard day; he had not expected the day would be this hard. He carved a sliver‑spoon from pine months back for no reason he could ever name. Now it had a reason.

He cleaned her wounds with warm water, hands rough but careful—ankles and shins bruised a jealous purple, knees scraped, lips split. Whoever did this had done it like work. She didn’t wake, only breathed in the shallow rhythm of people not yet invited back from the edge.

When the milk was blood‑warm he fed the babies, touching the spoon to the corner of a mouth and waiting for the reflex to take hold. The smallest cried—thin and angry at living—and that sound reached into him and scraped something soft. He didn’t let it show. He fed them all in turn and tucked the blanket beneath their chins. The howling outside fell off to a growl.

Her eyes opened sometime near midnight. They were the blue of high country in late summer, when the sky turns so clear you can see the work of God in it. She looked at the ceiling first, as if surprised it was there, then at him, then at the basket.

“My name’s Marabel,” she said, voice raw. “Marabel Quinn.”

“Silas Granger.” He put another split on the fire. Sparks lifted and died in the smoke‑stained rafters.

She wet her lips and tried to sit. Pain showed in the pinch of her mouth. He helped her prop with folded blankets. Her gaze clung to the babies—three small punctuation marks in a sentence that had nearly been ended.

“Who did it?” he asked at last.

“Joseph Quinn.” The name landed heavy. “My husband.”

The word husband did not sit right beside the wire wounds on her wrists. Silas’s jaw tightened. “Why?”

“I gave him daughters.” Her eyes flicked to the basket. “Three. He says a son’s the only proof a man is blessed.”

Silas looked at the stove door where the orange glow was steady and mean. “He’s wrong.”

“He has brothers,” she said. “Money. Men who ride when he whistles.”

“Let him whistle.”

The wind clawed at the eaves. Inside, heat began the slow work of pushing winter into the corners.

Hattie Cole rode up the ridge at dawn, shawl pulled to her chin, breath fogging in the cold. She didn’t bother with hello. “Word in Pine Hollow is Joseph Quinn’s telling folks you ran mad and stole his girls,” she told Marabel, then cut her eyes to Silas. “He’s put coin on finding you. Four men rode out of his yard at first light.”

Silas didn’t say a thing. He set his mug down and started for the door.

Hattie grabbed his arm. “You can’t square four with one.”

“I don’t have to square them. I have to slow them.”

She reached into her coat and pressed a small leather pouch into his hand. Dried lentils. A flask. A small roll of linen. “If you’re gonna be stupid,” she said, “be stocked.”

He nodded and left.

That day he worked in ways the mountain would understand. He set a false camp down by the south trail—coat on a fence post, a lamp hid behind a log to throw a man‑shaped shadow, a small fire fed with green pine so it would smoke more than warm. He rode his mare out half a mile and tied her where a hurried fool might. Then he circled on foot through spruce and aspen, making a noise where he wanted a noise, and none where it mattered.

They came in the first spit of snow at dusk—four men hunched in their saddles, hat brims pulled to their collars. The one in front had a scar that split his cheek like a river. He wore his mean like a medal.

“Granger,” he called, drawing up short of the porch. “We come with claim.”

“No,” Silas said.

“The woman inside is Joseph Quinn’s wife. That makes her his property. We’re here to return what’s his.”

“She’s not property,” Silas said. “She’s a person. And she’s not going anywhere with you.”

Silence. Then a sneer. “You reckon you can stop four of us?”

“Reckon you can ride into a blizzard and find out.”

They did not test him that day. The mountain had its teeth out and their horses were already blowing hard. The scarred man tipped two fingers off his hat. “Another time,” he promised, and wheeled away. Snow took their tracks as soon as they made them.

Marabel watched from the small back window, babies tucked against her. She let out the breath she’d been holding for hours. Silas came in, shook the cold from his coat, and hung it by the hearth. He warmed his hands, then turned and looked at her as if measuring whether she would run. She didn’t. She didn’t have anywhere left to go.

Days began to string together like beads. She moved without the flinch now, tending the girls, learning the inventory of Silas Granger’s small kingdom: the shelves of dried roots, the neat stack of pelts, the barrel of nails he’d scavenged and sorted, the single book on the shelf—the Good Book—thin at the Psalms because those were the pages thumbed most. He spoke little, which she found restful. When he did speak, he said only what was necessary, and all of it mattered.

One afternoon she found him at the bench outside, sleeves rolled, working a piece of cedar with a knife so sharp it whispered. That night, above the basket, there were three small plaques hung from leather thong. He had carved the names carefully and oiled the wood so the letters caught firelight: ELOISE. RUTH. JUNE.

No one had ever made their names a permanent thing. She pressed her fingers to her mouth so the gratitude would not jump out too loud.

The storm that brought them trouble rode in fast from the west, blew white so hard the windows rattled in their frames. The sky broke out of its banks and ripped at the ridge. The girls slept—by some mercy babies always find the opposite of noise—and Silas checked the shutters again, then stood a long time with his hand on the latch.

“Men,” he said finally, not bothering to look. He had felt them before he saw them—the way a hunter feels something turn the air. “Three.”

Her mouth went dry. He turned, slid the elk hide around her shoulders, and put a small knife in her palm. “Follow the creek,” he told her. “Keep low. If they catch you—” He didn’t finish. He didn’t need to.

She gathered two of the girls into the shawl and tied the third against her back. The knife was warm from his hand. “What about you?”

“I’ll be loud.”

He kissed each baby once. It was the smallest, most careful thing she’d ever seen him do. Then he opened the back door to a sheet of snow and pushed her into it with a gentleness that broke her heart more than any cruelty Joseph had practiced.

The knock on the front door came a minute later—hard and high with authority no man had given them. Silas opened to find Joseph Quinn himself, handsome in the way granite can be handsome, cold and polished and without mercy. Two riders flanked him.

“You took what’s mine,” Joseph said. “The girls bear my name.”

“They bear their own,” Silas said.

Joseph lifted his gun. “Move aside.”

A voice cut the storm. “You’ll lower that pistol, Joseph.” Sheriff Asa Mather rode out of the treeline with two deputies and Hattie Cole beside him, cloak snapping. Mather was a wide man gone to muscle and middle age, hat brim snowed over, eyes that saw the part of a story most men tried to hide.

Hattie pointed at Joseph. “You left your wife wired to a fence like she was a coyote. I reckon that’ll play poorly with the judge.”

Joseph’s mouth curled. “She’s hysterical. She ran.”

Mather’s jaw worked. “You can tell it under oath.” He nodded to his deputies. “Take their irons.”

One of Joseph’s men lunged. The butt of his rifle cut Silas at the shoulder and drove him back into the doorframe. Pain went white. Snow went red where it soaked the seam of his shirt. Silas didn’t fall. He came forward off the pain like men who have done hard winters do, and he would have put the man down hard if the deputy hadn’t been faster with the barrel of a Colt.

“Enough,” Mather snapped. “Joseph Quinn, you’ll come with us.”

Marabel stepped from the trees then, cloak crusted with snow, knife still in her fist, girls in the shawl. She looked like something the mountain had made. “Tell them,” she said to Joseph. “Tell them what you did.”

For a heartbeat, even the wind listened.

They took Joseph to Cheyenne for arraignment two days later, trussed like a steer and mad enough to chew nails. Hattie went along to swear what she’d seen and heard in town, and Silas rode because Marabel asked him to and because he wanted to, two reasons that felt like one.

Wyoming Territory had changed the way women stood in the world—gave them the vote in sixty‑nine and dared anyone to take it back. The judge in Cheyenne wore that history like a vest. He listened long to Sheriff Mather and longer to the midwife who’d delivered the girls and could recite, word for word, the curses Joseph had spilled when the third daughter cried.

Joseph’s attorney—thin, gray, mean in the middle—argued in a voice that oiled itself as it went. “A husband has rights,” he said. “A father doubly so.”

The judge took his spectacles off and polished them slow. “A husband has duties, Counselor. So does a father.” He looked at Marabel. “Mrs. Quinn, do you want a divorce?”

Her hands were steady where they wrapped the shawl. “I want my daughters safe.”

“You’ll have both,” the judge said, and struck the desk with his gavel.

It did not end the thing. It only changed its shape. Men like Joseph did not believe loss applied to them. He posted bail no sooner than he could and hired a pair of riders with eyes like spilled whiskey. Hattie heard their names in Pine Hollow and brought the news up the mountain in the dark like a lantern.

Silas didn’t sleep much those nights. He mended his traplines and moved his stock and taught Marabel to shoot because she asked and because it made his heart stop hurting when she hit what she aimed at. He fitted the east wall of the cabin with a second crossbar and set bells on the back trail that would sing if a hoof brushed them. He wasn’t waiting for trouble. He was preparing to end it.

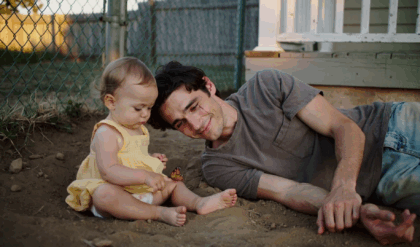

Days kept their shape anyway. The babies grew into themselves—Eloise first to smile, Ruth first to hold her head, June content to listen to the world like it meant to speak to her alone. Marabel’s color came back and with it a voice that could fill a room without raising itself. She taught letters to children from the lower creek using a slate Silas had bargained for with pelts in town. He watched her some afternoons, elbow on the porch post, knife idle in his hand, as she drew a crooked capital R and set a kid to grinning at the sound of his own success.

“Your girls will read early,” he said one evening.

“They’ll read the world first,” she said. “Then the books.”

He smiled at that. It was almost a laugh on him, though he hadn’t used one in some years.

When spring took hold proper, when the ridge went green and the creek argued with itself on the rocks, they opened their door to travelers—coal men riding between mines, teamsters belted with dust, two sisters from Illinois looking for the future they’d heard was out west, a violin man who’d played street corners in St. Louis until his bow arm shook and who could still wring a hymn out of four tired strings. Word ran fast that there was stew and kindness at Granger Ridge and a bed if you needed it.

They called the place The Hearth because that’s what it had become.

Joseph Quinn came back like a bad winter—later than you hoped, sooner than you feared, meaner than either. He brought two men and a court paper signed in Cheyenne that said, in letters large enough to make a bully happy, that he was owed a visit with his children under supervision. He wore clean clothes and a smile that had never been near a church.

Sheriff Mather met him at the Hearth’s porch and read the paper twice. “You’ll have an hour,” he said, voice flat as iron. “I’ll be right here. You touch her or those children rough, I’ll lock you in my own chicken coop and feed you scraps.”

Joseph looked past him into the room where Marabel stood, daughters perched on her skirt like small birds. “Afternoon, wife,” he said. The word made the babies go quiet. He knelt and reached for Eloise. “Let your papa see you.”

Eloise leaned back until she could feel Marabel’s legs. Ruth narrowed her eyes in a way that looked a great deal like Silas. June put her fist in her mouth and watched him like a hawk.

“You’ll talk to them kindly,” Marabel said. “Or not at all.”

Joseph’s smile frayed. “You been teaching her to sass, Granger?”

Silas didn’t answer with words. He stood easy, shoulder near the stove, hands at his sides, the promise of action in the looseness of them. Hattie sat at the table with a cup she didn’t drink from and the kind of expression that said she had seen a great many things and none of them impressed her anymore.

The hour ended as hours do. Joseph left with his jaw tight enough to crack a tooth. He returned three nights later without paper, without witnesses, without anything but his old mean and the conviction he could have what he wanted by taking it.

He came at moonset when the ridge went silver and the creek ran black. He sent one man to the rear and kept one at his shoulder and took the front himself with a crowbar. The bells on the trail sang and Silas was already up when the first blow hit the door. The crossbar held. The second blow smiled the hinges. The third found wood that had been choosing to give for a century.

Silas met him in the gap, not with a bullet but with a length of ash he’d cut for a tool handle, swung from the hip. The bar went into Joseph’s ribs with a sound like striking wet wood. Joseph folded but didn’t fall. He came up with a knife and a noise not meant for words. The man at his shoulder tried the window and met Hattie’s skillet for his trouble. The one in back found the trap Silas had dug for coyotes and learned something about humility.

It got ugly then. Real things often do. Steel scraped steel. Blood found wood. Marabel fired once into the porch post to remind the night whose house this was. The shot froze the room for just long enough for Mather’s voice to barrel up the yard.

“Hands where I can count ’em!”

Joseph went still. The men with him went stiller. Hattie exhaled like a prayer that hadn’t asked permission. Silas dropped the ash handle and stepped back. He realized he was bleeding at the forearm and the shoulder in twin bright lines and felt nothing of it beyond the fact of it.

Mather put irons on Joseph himself and took a long time doing it. “You mistook mercy for permission,” he said. “That’s where a lot of men like you go wrong.”

Joseph laughed. It had hate in it. “You think this ends me?”

“No,” Mather said. “I think it starts you ending.”

He wasn’t wrong. Joseph went from bad to worse to gone. He found a cell in Cheyenne and a judge who had less patience than the last. He found a lawyer who could no longer find the words. He found that money cannot always buy back the part of a man he throws away.

Marabel woke the next morning to the sound of her daughters giggling at the creek and Hattie in the yard cussing at a dent she’d put in her skillet. Silas slept for the first time in two days, one arm flung over his eyes to keep dreams from finding him. She stood a long time and watched him sleep. The mountain breathed around the cabin like it had chosen, finally, to be kind.

That afternoon she made bread and in the evening she took out a length of wool she’d been working and finished the last rows. It was a shawl deep as wine with small stitches in the corner—E • R • J—and beneath them a single word she’d built from patience and thread: WORTHY. She wrapped it around her shoulders and went to the porch where the light made the ridge gold.

Silas sat on the step with a basket of green beans and a look on his face she had learned meant thinking. She sat beside him and rested her hand on his. His fingers, big as they were, turned under her palm to hold without crushing.

“Thank you,” she said.

“For what?”

“For choosing us when you didn’t have to.”

He looked at the sky. “I didn’t have to keep breathing either,” he said, “but I’m partial to what comes after choosing.” A corner of his mouth moved. It might have been a smile.

They married two weeks later because it felt like the right next quiet thing. No preacher. No papers beyond what the judge had already given. Hattie put wildflowers in a cup and set it on the table. Mather stood by the stove with his hat off and his hair trying to remember what a comb was for. Silas put a string of carved beads on the girls’ small wrists, one for each, smooth with oil and patience. For Marabel he had nothing but his hand. She took it and, in doing so, had everything.

Life did what life does when people let it. It stretched. It softened. It got loud with little feet and quiet with the sort of peace that sneaks up on you when work is honest and days are full. Travelers came and ate stew and slept on quilts and left with bread in their pockets they pretended not to find until the first hill. The violin man came back and taught Ruth the bones of a hymn. Eloise learned to track. June sang all the time because songs kept finding her whether she meant to or not. When the first snow of the next winter came it felt like a visitor, not a threat.

Sometimes at night, when the fire signed its last few notes and the ridge went black enough to show every star there was, Silas lay awake and listened to the four breaths he could hear and the thousand he could not. He thought about the fence post and the wire and the part of himself that had woken when a stranger’s baby cried on his land. He did not have words big enough to name that part and would not have used them if he did. He knew this: the mountains had kept him alive. The woman and her girls had given him a reason.

Years went and took their tax and paid their wages. Joseph Quinn’s name stopped meaning a shape in the doorway and started meaning a warning parents used on boys who thought cruelty made them men. The Hearth grew until it was drawn on trail maps in pencil and then in ink. Folks said if you got lost on the Snowhorn, follow the smell of bread and smoke and the sound of a woman humming a tune that knew your heart before you did.

When the territory finally turned state and the railroad sent its iron thread a little nearer, people came with stories to trade for supper. A schoolteacher from Illinois stayed a season and taught not just letters but the notion that a woman’s mind could light a room. A veteran nobody knew what to do with found reasons to wake in the morning that had nothing to do with the past. A widow with a son learned you can start over at any month of any year and that sometimes a ridge will take you in like a relative.

On a summer evening years after the fight on the porch, a rider came up the switchback slow, hands raised before anyone needed to ask. He was young and scared enough to admit it. “I need help,” he said.

Silas stepped out and nodded like he’d been expecting the words his whole life. “We got help,” he said. “We got stew.”

Marabel came to the door with flour on her hands and the shawl at her shoulders and three girls behind her, no longer babies, all angles and light and the beginning of opinions. The ridge held its breath like it liked the look of them. The wind came through the spruce soft as a blessing. Somewhere down in Pine Hollow, Hattie Cole was telling a story at the mercantile and leaving out the parts that made her look like a saint and putting in the parts that made other people look exactly as brave as they had been.

There are places in this world that fix what’s broken not by pretending it never happened but by building something stronger over the break. Granger Ridge was one. The Hearth was another. And the four people who made them—five if you count the mountain, and you should—kept on choosing each other, day after workday, night after storm, until the choosing itself became a kind of law. A law older than paper. A law colder than wire and warmer than fire. A law that says: here, on this ground, you are not what was done to you. You are what you make next.

The wind still howled some nights. That was its nature. But in a room with four walls and a stove that grumbled and a table nicked by knives and elbows and time, the sound of it could not get in. It pressed its old face against the windows and then went on down the ridge to bother some other place where people hadn’t yet learned how to hold fast. Inside, a woman hummed and a man cleaned a gun he prayed he’d never need again and three girls argued about the ending of a story that had not ended at all.

And far off, past the last switchback, a fence post leaned and fell at last, the wire sloughing to the ground with a sound like the loosening of a grief. Snow would cover it come winter. Grass would take it come spring. No one would remember where it stood. That was fine. There were better things to remember.