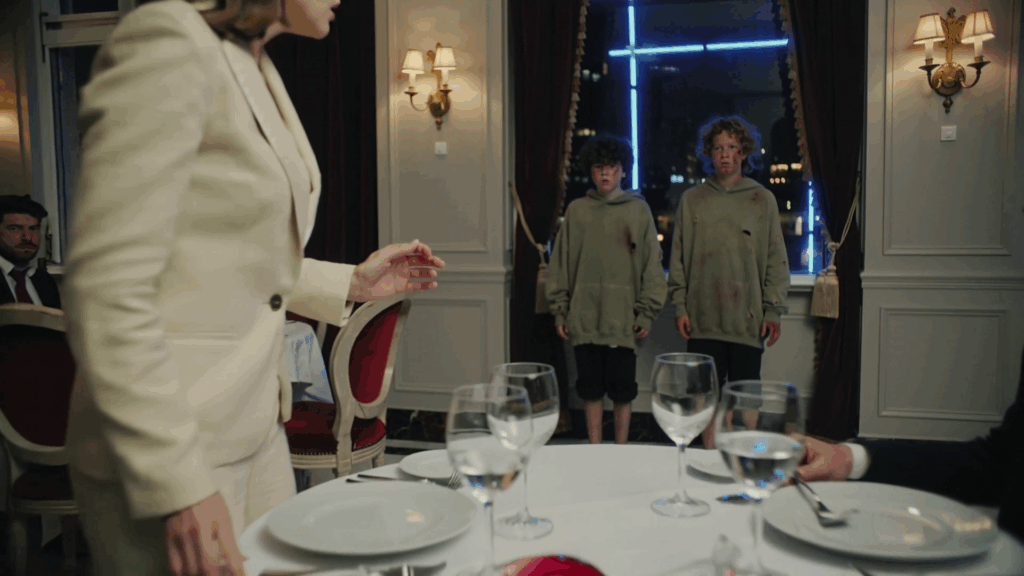

It began with a teardrop sliding over diamonds. Eleanor Moore’s bracelet—a neat lattice of baguette stones fastened by a platinum kiss—lost its clasp and slipped along her wrist as if pulled by an unseen tide. The murmur of Le Rivage quieted to a clink of glass and a violinist’s sigh as two boys hovered in the restaurant’s gilded doorway, hollow-eyed and shivering in their threadbare hoodies.

“Ma’am,” the older one said, voice careful, as if sound alone might shatter the crystal and spill them both back onto the sidewalk. “Could we have some of your leftovers?”

Eleanor’s partners—Richard Van Dorn with his cuff links and opinions; Gloria Chen with her careful, blade-sharp smile; and Lionel Kincaid, who never stopped calculating—turned as one. A flurry of judgment gusted across the linen. The maître d’ began moving, hand lifted to intercept. The waiter hovered with a silver tray. The violin strained to hold its note.

Eleanor rose a fraction from her chair. The cream wool of her suit whispered. Her mind did not so much think as flood. Because the boy’s eyes—hazel with a flake of green like an old bottle pulled from river silt—were her own. The slope of his cheek, the notch in his left eyebrow, the way he stood slightly forward on the ball of one foot, ready either to run or to leap—these were the private mappings of her life.

“James?” Her voice was a leaf shaken loose.

The older boy blinked. A heartbeat. Two. The name trembled in the space between them like something fragile and radioactive.

“How do you know my name?” he asked. The younger boy—wiry, dark-haired, ten at most—gripped the sleeve of the older one’s hoodie. Street-scratched knuckles. Blueed lips. A hunger like winter.

Eight years vanished and returned in a single breath. Night. Rain. Headlights blooming like white flowers on wet pavement. A scream of metal and then nothing. When Eleanor woke, the hospital air tasted like coins and antiseptic. They said her child—her only boy—had been in the back seat. They said the search teams combed the embankment until sunrise. They said the river was merciless.

They said there was no body.

Eleanor stood now, her chair legs whispering back across the floor. “James,” she said again, and the name was both prayer and plea. “It’s me. It’s Mom.”

He edged backward a step, jaw tight. “No. She’s dead.”

“No.” The word broke. She didn’t care that the room was watching—New York’s whispers braided with wine and butter and curiosity. She didn’t care about Richard’s contracting eyebrow or Lionel’s anxious glance at the gold watch he wore like a second pulse. She moved around the table, past the cut-glass salt cellar and the pink ruin of roast duck.

The maître d’ tried to intercede. She shook her head once, sharply. “Bring them food,” Eleanor said. “Anything. Everything.” And to James, kneeling so her eyes met his, so he could see the truth bare in them: “I never stopped looking for you.”

He did not run. That was the first miracle.

The second was small and ordinary: the younger boy’s eyes locked on a ramekin of crème brûlée and—after a quivering glance at James—his hand drifted to the spoon. The crack of caramelized sugar under the spoon’s back sounded like winter ice. He lifted a bite as if it might vanish. It did not. He took another.

“Tommy,” the older boy whispered, a warning and a mercy all at once.

“It’s okay,” Eleanor said. “Eat.”

Tommy ate. James did not. He watched Eleanor with a gaze older than his face, measuring with scales forged in alleys and laundromats and the suspicious geometry of survival.

Richard cleared his throat. “Eleanor,” he murmured, pitched for her alone. “This scene—there are reporters who dine here. Tomorrow’s headlines—”

“Let them write,” she said without turning. “They’ve written worse for less.”

“You have a closing tomorrow with the Barclay Tower group,” Lionel added quietly. “Eight hundred units. The city’s on the line.”

She looked at him. “The city will be there tomorrow. My son is here now.”

The room exhaled at her decision. It was not the decision that made them breathe, but the old hunger in them to watch a boundary—the invisible fence between money and need—move.

Her driver idled the Cadillac along West 46th under a sky flushed with a wet neon. James and Tommy followed Eleanor through the gusting door as if approaching a strange country. The leather was too soft, the scent too rich. Tommy’s fingers worried the seam of his sleeve until a thread unspooled across his lap like a tiny road out of nowhere. Eleanor wanted to take James’s hand. She did not. She let him keep the space he needed between the door and himself, between this new story and the old one he had survived by telling.

On the thirty-fourth floor, the penthouse opened like a long-held breath. Wool rugs. Quiet art. A window the size of a confession. The city yawned beyond, each rectangle of light a human proof.

“You can shower,” she said, voice gentle, careful not to pour. “There are towels in the linen closet. Robes in the guest room. I’ll—” She caught herself before she said I’ll order room service because this was no hotel, and because hunger should learn to trust a kitchen again. “I’ll make grilled cheese,” she said instead, surprising them all, herself most of all.

Tommy’s head snapped up. James’s mouth flattened, suspicious at the kindness. But the corners of his eyes—those green-flake hazel eyes—softened by one grain.

They ate at the marble island, the sandwiches crisp on the outside, soft as forgiveness within. The boys drank milk as if it were a secret. James paused midway, the glass tipping, as if his body had to remember this motion belonged to him. The city wind nosed the window. Somewhere far below, a siren stitched a red thread across the avenue.

“Where do you sleep?” Eleanor asked, and when the silence sharpened, she added, “When it’s cold.”

“By the laundromat on 10th,” Tommy said, before James could stop him. “Under the dryer vents when they’re on. It’s warmer there.”

James shot him a look. Tommy stared down at the crust on his plate as if it were a map.

“Do you have anyone?” Eleanor asked. “A caseworker, someone at a shelter who knows your names?”

James shook his head once. “Names are trouble.”

Eleanor breathed against the ache of that truth. “Here,” she said quietly, and slid a folded, time-creased photograph across the counter. A boy grinning at the edge of a summer lake, hair shock-lit by July, a missing baby tooth flashing like a wink. “I kept it with me,” she said. “Every day.”

James did not touch the image. He looked at it as if it might burn him. Then he leaned in, closer, and a breath he did not want to give escaped him. “I used to hate that shirt,” he said, and his voice tried and failed to be indifferent. “It was scratchy.”

Eleanor smiled through a mist. “You refused to take it off because of the dinosaur.”

Tommy risked a point of attention. “You liked dinosaurs?”

James looked at him: a glance that said be cool, don’t look so hungry for a normal life. “I liked the big ones.”

“Of course you did,” Eleanor said softly. “You liked the T. rex because his arms were small and you thought it was funny.”

For a long time that night, after the sheets unfolded their clean rivers and the guest room door learned the weight of new breathing, Eleanor sat in the hallway on the floor. It was an old habit—how she slept beside cribs and hospital beds, how she waited outside conference rooms while deals decided their angles. She listened to the steadying of James’s breath, to the small snore that threaded through Tommy’s. When she finally slept, her cheek against the cool of the wall, her last thought was not a thought but a vow.

In the morning, she called Dr. Alana Serrano, who specialized in children who did not have the luxury of choosing their stories. Alana’s office smelled like peppermint and old books. James sat with his hands jammed under his thighs, and Tommy fixated on the fish tank, specifically on one small neon tetra who insisted on swimming against the filter’s current until its silver-blue body shimmered with a stubborn joy.

“Trauma rearranges time,” Alana said to Eleanor privately, after the boys’ first session. “Don’t rush the past to catch up. Let the present be safe long enough for the past to walk in by itself.”

So Eleanor slowed. She canceled a panel in Miami, a gala in D.C., a ribbon cutting where she would have smiled for cameras and pretended that buildings were the same thing as homes. She started waking early to cook oatmeal. She walked James to a public school, the one with a principal who looked her in the eye and said every child deserves a re-entry. She learned the delicate choreography of not touching until he leaned the smallest degree in, of letting the silence have a chair at the table until the silence had been fed enough to excuse itself.

When he spoke about the foster house, he did so at night, while the city tucked itself into its lighted boxes. “They weren’t all bad,” he said, as if that absolved him from sounding like he wanted mercy. “But the last one—he locked the pantry. If you wanted food, you had to scrub the garage floor until the water ran clear, and the water never ran clear because the concrete was old and stained, and that was the point.”

Eleanor’s hands wrapped the mug until the heat began to ache. “I am so sorry,” she said, and kept her voice even because rage would be her indulgence, but it would not be his safety.

“He taught me I could outlast the mop,” James said with a one-shouldered shrug that was not casual at all. “Tommy was smaller. I made sure he ate. We left at night. I knew how to push the window screen. We learned where the cameras were at the convenience store so we could steal without stealing too much.”

“What is stealing too much?”

“When they notice and call someone.”

He did not cry when he spoke of the river or the night of the crash. He did not speak of them at all. But once, in the middle of a Saturday, while he and Tommy studied a glossy pamphlet for the Museum of Natural History and argued as if the future were a sports team with positions to fill, Eleanor hummed without thinking. A simple thread of notes, nothing operatic—just the old lullaby she had made up about fireflies and porch light and a summer that never ended. The argument stopped mid-velocity. James’s head turned like a compass needle finding north.

“I know that,” he said quietly, almost accusing. “Why do I know that?”

Eleanor swallowed. “Because you were the only audience I ever had that clapped for me before I began.”

They went to the museum. They stood beneath the blue whale that hangs like a benevolent god from the ceiling. Tommy’s mouth fell open. James pretended not to be impressed and then betrayed himself by saying, in a careful tone as if reading a street sign, “Balaenoptera musculus.”

At night, when he slept, he began to murmur. Names of streets, names of shadows, the sound of a dryer thudding quarters like a clock. Once: “Hold on, Mom,” breathed into the pillow as if the pillow were a raft.

The first reporter camped outside the building on a Wednesday with a coffee cup and a windbreaker. By Friday there were five more, plus a woman with a microphone the color of grapefruit who called Eleanor “the real estate queen with a missing prince.” Eleanor ignored them until one afternoon a lens skewered the space between James and the school gate.

This time she did not ignore. She walked to the cameras with a sharpness that made the air draw back. “I will not feed my son to your page views,” she said. “Back up.” The last word carried an old weight, and the men with the cameras recognized it, not because they respected her, but because they recognized the threat of someone with both money and nothing to lose.

She hired security not because of the reporters, but because of what men like the one in the foster house could become when either threatened or hungry. She had the door locks rekeyed, installed a floor safe for papers that mattered, and, one night after midnight, when the city’s lights were a little tired and honest, she drafted a trust in Tommy’s name because promises should be notarized where possible.

“Why are you doing this for him?” James asked, not looking at her.

“Because you did,” she said. “And because no one did for you when they should have.”

He chewed that like gristle and then swallowed it like bread.

By December, James had a friend named Malik who wore a backpack like he was training for a march across a state. Tommy discovered a library branch where Ms. Kelly saved comic books behind the desk because she believed in rationing joy. Eleanor discovered she could be two kinds of person at once: the woman who negotiated zoning variances with a grin and a sharpened clause, and the mother who knew which drawer had the bandages printed with dinosaurs that could turn pain into a story about teeth.

On a morning spiked with frost, James stood at the window and watched a man shovel the portico below. “People think money is a wall,” he said. “But it’s just a different weather.”

“Who told you that?”

He shrugged. “Myself.”

“You’re right,” she said. “But good walls keep the wind off while you heal.”

He nodded, then reached into the pocket of his hoodie and handed her a crumpled receipt. On it, in the shaky pen of a teller unused to kindness, was a savings account number with two small deposits beside Tommy’s name.

“I want him to have something that’s his,” James said. “From me.”

“Then you will.”

Eleanor’s work did not stop; it reoriented. She cut a deal on Ninth Avenue that required the developers to include a wing for youth transitional housing. She met with nonprofits who had learned how to stretch a dollar until it played music. She listened more than she spoke. She learned the names of the women who ran the kitchens and the names of the men who slept in the stairwells because the shelter doors were full. She learned there is a sound a child makes when a warm meal arrives that no orchestra can replicate and no donor gala can stand next to without blushing.

She bought an old brick building in Hell’s Kitchen that used to be a plumbing supply warehouse, and together with Alana and Malik’s mom, who knew how to weld, and Ms. Kelly, who could talk a city inspector into remembering his own first book, they turned it into The Firefly Home. There were lockers that locked without swallowing hands, and showers that did not go cold mid-hope, and a room with windows that looked like the idea of tomorrow. The day the inspector signed the certificate of occupancy, a dusty sunbeam split the hall like a golden highway.

At the opening, James wore a blue shirt he said was not him and then admitted it could be, in the right light. He did not want to speak. He stood to the side, watching the way kids entered rooms like questions. When someone from the city—slick hair, crisp voice—asked Eleanor to say a few words, she looked at James. He gave the briefest of nods, which was the same, in the grammar of his heart, as a standing ovation.

“Sometimes,” Eleanor said into the microphone, and her voice carried like steam off winter grates, “the world tells a kid that they are an accident to be cleaned up. Sometimes it tells a mother that grief is a private luxury. Sometimes it tells both that the door is for other people. This building is a door for the people who were told to wait in the alley.”

A hand rose at the back—one of the kids, brave enough to question in a room full of adults learning to clap for themselves. “What happens if we mess up?”

“Then we will make room for the mess,” Eleanor said. “That is what a home is.”

James took the microphone not because he wanted to but because sometimes wanting is smaller than necessary. He looked briefly at his shoes and then at the kids and then at the ceiling, where flies of dust wandered the light like it was summer. “Sometimes life takes everything from you,” he said. “So it can show you what’s left when everything is gone.” He cleared his throat. “If you’re here, it means you survived. That means you’re good at something you didn’t ask to be good at. Maybe we can find out together what you actually want to be good at.”

The applause was the right kind—not the gala kind, not long and performative, but warm enough to be a blanket and brief enough to leave room for the next thing.

That night in the penthouse, after the guests and the speeches and the way the building’s bones felt new because they had been asked to hold a different kind of weight, James stood at the glass with the city reflected faintly on his face. He hummed, barely. Eleanor hummed back without meaning to, fitting her notes to his until the small song found the place it remembered to land.

“My father?” he asked suddenly, the glass catching his breath and smearing it into a ghost. “Where is he?”

Eleanor answered the way Alana had taught her: with the truth, and with only the piece of it that would not break the hinge of the door they had built. “He left when you were small,” she said. “He didn’t know how to stay. He sent a few letters. I didn’t keep them. I thought I was protecting you. Maybe I was protecting me.”

James nodded slowly, absorbing the fact as if it were weather. He did not ask for more. He did not forgive. He did not have to. He let the knowledge find its shelf.

Winter in New York has a sound like metal choosing to be cold. The day the first snow fell, Eleanor woke before light and watched flakes powder the city into a softer version of itself. She brewed coffee and warmed milk and set out cinnamon because Tommy had announced that cinnamon made mornings “more like cartoons.” The boys shuffled in—Tommy with hair that loved its own chaos, James with that watchfulness that would, one day, become something like ease.

“School may close,” Eleanor said.

“Please say it like a wish,” Tommy said.

She laughed, and the sound felt unfamiliar, not because she didn’t laugh often, but because this one was made of three people and toast.

At noon, while the snow made the city forget its edges, a letter arrived in an envelope with a law firm’s name stamped near the corner. Lionel had sent it, with a note pinned by habit: Thought you should see this before it becomes a piece of someone else’s leverage. Inside: an affidavit, years old, from a private investigator who had once worked for a rival. The affidavit swore that, eight years ago, someone had called off a search on the river twenty-four hours early for “cost containment.” A signature no longer in office marked the bottom in ink that had not faded enough.

Eleanor read it twice. She watched the ice form around her coffee. She felt the old rage begin its long, hot sprint. For a minute, she let it run. Then she called Alana.

“He does not need a war,” Alana said. “He needs breakfast tomorrow.”

“I can do both,” Eleanor replied, calm as an oath. “And I can make sure the next boy on a riverbank gets a full day more than a budget line.”

The lawsuit did not trend so much as hum. It wasn’t the kind that made evening news; it made policy memos and winter meetings. Eleanor did not give quotes. She filed FOIA requests with the thorough impatience of a woman who had waited at the wrong doors for too long. She learned the names of the dispatchers who hadn’t slept that week, and she sent them gift cards not because it would help but because kindness is a kind of crowbar when used correctly. When the settlement came, it came with new protocols attached and a line item that would fund overtime so that searches could widen instead of thicken into excuses.

James watched without watching. He navigated his own map—the one that stretched from the laundromat to the whale’s blue belly to a boy named Malik who wanted to learn to fix things and a woman named Ms. Kelly who taught poetry that sounded like a ladder thrown from a window to a kid in a courtyard. He did his algebra. He forgot to take out the trash. He remembered to check the locks before bed and then, one night, didn’t.

Spring edged the city green. Tommy grew an inch and three opinions. Eleanor found herself arriving late to a board meeting because a sandwich needed to be cut into triangles instead of rectangles, and the geometry of love won.

One evening in May, a knock sounded on the penthouse door not like a request but like a code. Security checked the camera and looked uneasy. The man in the hallway wore a suit cut to erase the person inside it. When the door opened, he smiled—a practiced flex. “Ms. Moore,” he said. “I’m with Barclay Tower Holdings. We’re concerned your newfound philanthropy might complicate our rezoning timeline. The city listens to you. Perhaps we could discuss—”

Eleanor waited until he finished pretending to be polite. “People used to try to buy my conscience,” she said. “Now they try to rent it by the hour. Neither model scales.”

He glanced past her, into the apartment, searching for something to hold against her. His gaze snagged on a pair of sneakers by the door—small, scuffed, dinosaur laces undone. He did not understand that he had just seen the axis of her world.

“Good night,” she said, and closed the door.

On the last day of school, James stood just inside the gate, a certificate in his hand for something named not with the vocabulary of genius but with the slower, harder words—attendance, effort, citizenship. Tommy waved his own like a flag. The air smelled like sidewalks warming and cheap perfume and the kind of hope that makes teachers cry in their cars in July.

To celebrate, Eleanor suggested pizza. The boys suggested the park. They carried slices on paper plates that buckled and laughed when the grease outran the crust. A group of kids played stickball, the bat a scarred broom handle. An old man in a Yankees hat kept score without paper. Pigeons hoped for crusts and were rewarded as life permits.

“Can we go by the river?” James asked after, and the question hung between them like a bell.

They walked to the place where the water shouldered the city with its old, indifferent muscle. James stood with his hands in his jacket pockets and watched the current write its endless sentence. He did not speak. He did not need to. Eleanor stood beside him and did the rarest thing money grants—the ability to take time and stand still inside it.

“Do you want me to tell you everything I remember?” she asked at last.

“Not today.” He glanced at her. “But someday, yes.”

“Someday,” she said.

He took a breath you could have rowed a small boat across. Then he put his hand—longer now, less boy and more bridge—into hers. Not like a child, not like a drowning person, not like someone borrowing a grip. He put it there the way people put a picture on a wall and step back to see if it is level.

That night, back home, he rifled a kitchen drawer and emerged with rubber bands and a handful of paper clips. “I want to build something,” he said, unsure whether he could want such a thing. “Not big. Just… something that holds.”

She cleared space on the counter. She made a bowl of strawberries. Tommy contributed commentary worthy of a sports broadcast. They built a small bridge between two water glasses and then, because the world often rewards the humble with a nudge, the bridge held.

Summer hummed like a window unit. The Firefly Home filled and emptied with the tidal rhythm of teenagers—some staying, some circling, all of them learning the weight and lift of a key that is theirs. Eleanor sat on the floor with kids and budgets, with receipts and stories. She watched James teach Tommy how to count screws into a jar so you could find them later. She watched him laugh at something stupid on a screen and then stop laughing because he had surprised himself with how easy it came, and then start again because he could.

One night, the elevator dinged and a woman stepped out who walked like she had taught herself not to be afraid of rooms. Mid-thirties. Brown hair in a knot. A scar along her thumb like a hyphen. “I’m looking for a boy named James,” she said to security, to the floor, to the air. “I fostered him. I failed him. I… I heard about the shelter. I wanted to say sorry.”

James listened from the hall. His body knew the danger of this kind of apology, the way it can shift weight onto the person who is offered it. He did not go to her. He did not run either. Eleanor stepped into the space. “We don’t ask our kids to carry our adults,” she said gently. “If you want to help, we always need math tutors on Tuesdays.”

On Tuesday, the woman showed up with a textbook and two sharpened pencils and questions that had nothing to do with pain. James watched her teach a boy named Daniel how to find x where x didn’t want to be found. He did not forgive. He did not have to. He started to believe in Tuesdays.

In October, a year to the night since the diamonds slipped and the boys appeared and the room learned the taste of its own silence, Eleanor returned to Le Rivage. She did not reserve the private room. She chose a table near the window, where the city’s reflections could be mistaken for ghosts and then learned to be lights. James and Tommy flanked her. Richard arrived late and with a bouquet he pretended was for Tommy because admitting it was for Eleanor might make him human.

The violinist lifted his bow and paused. “Do you have a request?” he asked, and because New York, for all its cynicism, knows a story when it is living one, the room listened for the answer.

“Something small,” Eleanor said. “Something that sounds like home.”

The musician played a tune that could have been anything and therefore was everything—the kind of melody people hum without knowing it, the kind that catches on kitchen air and school hallways and stairwells and carries itself like a candle from face to face.

Tommy demolished a crème brûlée with the confidence of a boy who no longer fears abundance. James ate duck and then explained to the waiter, with an earnestness that should be bottled, that Balaenoptera musculus is the largest animal to ever live, and the waiter nodded like he had always known.

A family at the next table—tourists, possibly Ohio, hopeful—watched with the unabashed interest of people whose hearts have not been told to sit down and be quiet. Their daughter waved at Tommy. He waved back, a lord of the small empire that was his.

When the check came, Eleanor slid her card across the linen like an old ritual now made holy by new meaning. The maître d’ did not try to remove any boys from any doorways. The doorways had moved.

Outside, the October air braided itself with steam and laughter and taxi horns and the impatient ballet of crosswalks. James took Eleanor’s hand not as a test but as a habit. Tommy skipped ahead and then back. The city, which had once taken everything from them, offered itself as a map with more than one route home.

Later, in the penthouse with its window that had learned their story, Eleanor watched James stand at the glass, a tall boy with a man beginning to draw its outline. He did not flinch at sirens now. He did not keep his shoes on to sleep. He left the hall light on for Tommy, and on nights when Tommy forgot to be brave, James hummed two lines of a melody about fireflies under a summer sky that did not end.

Eleanor sat with her coffee going cold, and for once let it. Wealth had taught her too many lessons she’d had to unlearn: about speed, about scarcity disguised as abundance, about doors that open only one way. Motherhood, when it returned from the river with a boy taller than his memory, taught her this: sometimes the richest thing you can do is stay.

Before bed, she opened her laptop and typed a message that had been gathering at the edges of her mind. She did not polish it. She did not hire a strategist for it. She clicked post:

If you see a child on the street, don’t look away. That could be someone’s James. If you have a spare hour, bring it to a shelter. If you have a spare kindness, spend it like it’s going out of style.

By morning, the message had traveled like those summer fireflies, small, lit, unstoppable. Volunteers showed up with casseroles and questions and cots and the kind of clumsy, beautiful energy that makes bureaucracy crack its knuckles and get out of the way. A boy from Queens sent five dollars. A woman from Tulsa sent a quilt. A retired firefighter from Staten Island showed the kids how to check smoke alarms and then stayed for three hours to listen to a poem about a ladder.

James scrolled through the messages with a look that would never be quite trust and would always be something like wonder. “Mom,” he said slowly, the word now less an experiment and more a room with furniture. “Do you think…” He stopped, started again. “Do you think this stays?”

“Not by itself,” Eleanor said. “But we do.”

He nodded. He looked out at the city—the complicated, broken, shimmering engine of a place—and then back at her. He placed his palm against hers, fingers matching as if measuring some shared future. Outside, the lights blinked, and inside, the quiet did not mean an absence but a presence large enough to fill a home.

Sometimes wealth looks like steel and glass and zeroes. Sometimes it looks like grilled cheese at midnight and a robe that hangs too big on a boy in a room that smells like laundry and cinnamon. Sometimes it looks like a song hummed between two voices until it finds the notes of a life.

That night, the lullaby about fireflies threaded the dark again. And when it ended, the silence that followed was not empty but full—of breath, of the soft click of a lock set, of the city outside agreeing to stand guard for one more hour while the people inside learned, again and again, how to stay.