When Emily Parker married Daniel Whitaker on a blue‑sky Saturday in late June, the whole town of Fenton Hollow, Vermont seemed to shimmer with permission. Sunlight scattered across the church’s stained glass like confetti. The maple trees along Willow Street stood heavy with leaves, their shadows flickering across the old white clapboards of St. Luke’s. Emily wore her mother’s veil, a delicate web that tickled her shoulders when she laughed, and Daniel—quiet, steady Daniel—held her hands like a man who knew how to tend to small, important things.

They were twenty‑nine and thirty‑two, old enough to have regrets, young enough to call that feeling hope. Daniel had an engineer’s mind and a carpenter’s hands; he could picture a thing before it existed and make it true—a shelf that never sagged, a frame that wouldn’t warp in the winter. Emily was a school counselor at Fenton Hollow Elementary, the one kids trusted when secrets got too heavy. She had a way of sitting that meant I can hold this. She had a way of seeing that made children believe blue could be a verb.

The reception was behind the Grange Hall with checked tablecloths and jars of daisies and a rented dance floor that clicked underfoot. Margaret—Daniel’s mother, Margaret Whitaker—wore navy chiffon and sensible shoes and cried into a handkerchief that had belonged to her own mother. She had lost her husband, Henry, a year earlier to a quiet heart that had simply decided it had loved enough. Since then, Margaret had become the sort of widow everyone asked after at the grocery store and during the offertory at church; the kind of woman whose porch light burned like a star other widows set their clocks by.

It wasn’t a secret that Emily and Daniel would be moving into the Whitaker house on Birch Lane. The house had good bones and bad wiring, and the property taxes made everyone in town shake their heads and say, Lord help us all. But the plan was temporary. Just until they saved for their own place, Emily would explain, smiling, the way you smile when you want someone to believe you. Margaret would stay where her memories already knew the floor plan. The guest room—future child’s room, Emily whispered to herself sometimes—would become theirs. Daniel would fix the sagging porch; he’d rewire the kitchen; he’d install a rail along the back steps where the ice gathered in January. They would be a family, the three of them. There was no shame in that. It was Vermont. People stacked wood, shared driveways, tuned one another’s snowblowers.

On their wedding night, after the sparkler send‑off and the hugs that lasted three beats too long, Emily leaned her head against Daniel’s shoulder in the back seat of the borrowed Crown Vic and watched as Birch Lane rose to meet them like a familiar hymn. The house waited beneath an open sky, its windows soft with lamplight. Margaret had left the porch light on and a note on the kitchen counter: Welcome home, my kids. There was chicken salad and lemonade in the fridge and a lemon cake under a glass dome on the table because joy is nothing if you can’t slice it and hand it to someone you love.

For the first few weeks, the house learned the new rhythm of three. In the mornings, Emily would hear Margaret’s kettle click to life and the faint scrape of toast. Daniel’s boots would thump the mudroom tiles. Emily would pull on a sweater and pad down to the kitchen where Margaret would hold out a mug. Olivia Benson, Margaret would say, by way of explaining her love for strong coffee and righteous outcomes on TV. Emily would talk about a boy who couldn’t sit still until they put comic books under his chair legs, or a girl who drew rain with a ruler because disorder scared her. Daniel would circle a line item on a hardware store receipt or sketch a load‑bearing beam on the back of the envelope from the electric bill. It felt like a beginning you could plant your hands in, like loam.

Then night came.

It started the second Tuesday after their honeymoon—subtle as breath. Emily woke to the shape of Daniel getting out of bed, the mattress returning to itself without complaint. The digital clock said 12:17. His feet found the floor with the caution of a man sneaking out of a narrative he wasn’t sure belonged to him. Emily watched his shadow cross the room. The door latch whispered. She could hear the soft cadence of steps down the hallway, then nothing, then the quieter nothing of someone easing a door shut a few rooms away.

At six he was back beside her, smelling faintly of antiseptic and the peppermint lotion Margaret kept by her sink. When the alarm sang, he kissed her shoulder. Morning, M, he said, and it was as easy as breath to pretend the night hadn’t happened.

She didn’t ask the first time. It is a courtesy newlyweds extend to one another, this permission to keep small mysteries. There are drawers you do not open yet, scars you do not trace. Emily gave him that, and then gave him the next night, and the one after, because love is generous and also because she did not have language for the disappointment that nibbled at her ribs like field mice.

The fourth night she listened. She heard the faucet run down the hall. She heard a low voice, then Daniel’s, then silence. In the morning, while Margaret watered the geraniums on the windowsill, Emily said, Dan, are you—

He didn’t let her finish. Mom gets anxious at night, he said. It’s been worse since Dad died. I sit with her until she falls asleep. He wore the expression men in New England deploy when the weather is the weather: resigned and practical and not especially interested in discussing it. I’ll be back sooner, he added, as if punctuality were the shape of comfort she needed.

But sooner had a way of becoming sunrise. Weeks gathered. Then months. The bed was bigger without Daniel, which is to say it was lonelier. Emily learned the shape of the ceiling in the dark, where the plaster had cracked into a map of rivers, where a spider had taken up a careful life in the southwest corner. She learned that the coyotes called to one another across the fields like teenagers on a party line. She learned that there were a hundred ways to lie still and none of them felt like her.

People in town noticed, because of course they did. Fenton Hollow noticed everything, stored it, and returned it to you in jars labeled with the very best intentions. At the farmers’ market, women with hands that had kneaded dough their entire lives would touch Emily’s wrist and say, Isn’t it wonderful? A man who loves his mother like that? At church, Mrs. Shipley would squeeze Emily’s knuckles during the Passing of the Peace and whisper, You will be blessed for your patience, dear. Emily smiled her polite smile and began to hate Sundays a little bit.

Margaret never said a word about Daniel’s nightly departures. She was kind to Emily in the way of women who have survived: more casserole than conversation, more doing than dwelling. She stocked Emily’s favorite chamomile tea in a jar with a label maker’s neat font. She left coupons on the counter for things Emily might like if she had space to like them. And sometimes, when the porch light drew a teardrop of moths and the evening smelled like rain warming a road, Margaret would look toward her bedroom and her mouth would tighten, as if bracing against a pain no one else could see.

By their first anniversary Emily had made a truce with it all. She told herself stories about duty and grief, about a woman who had slept beside a husband for forty years and now lay in a bed big enough to drown in. She told herself she was decent for understanding. She told herself the word season a lot, the way devout people do when they need time to be obedient to a hope that doesn’t yet look like itself. And in the quiet of those dulled narratives, Emily stopped telling herself other things: that she wanted a child, that she wanted a house with a front door they both unlocked at the same time, that she wanted to be the place Daniel went at the end of a day. She tucked those wants into the pocket of a coat she rarely wore. She told herself she’d know when to put the coat back on.

By their second anniversary, the truce felt more like a stalemate. The school year had sharpened into winter. The kids came to Emily with cheeks chapped and words that arrived in jagged pieces. She wrote copious notes. She drove home along roads now narrowed by snow, thinking of a boy who had learned to name the panic in his chest after an animal he could draw on paper and then crumple into a quieter shape. She imagined the way healing sometimes looks like attention. She parked beneath the maple and carried the day into the house, set it down, picked it up again.

That night, when Daniel rose from the bed at 12:11, Emily felt something in her go with him. It wasn’t rage; rage is an instrument you can hear. This was the soft failure of a bridge left unriveted.

She followed.

She learned early in her life not to betray the floorboards. Her father had been a sheriff’s deputy, the kind of man who loved Emily with both hands. He taught her how to move across a room without announcing it, how to notice the shape of a shadow, how to set down a glass without the table arguing back. She stepped into the hallway, the grain of the wood cool underfoot, the house full of sounds it made only at night—the pulse of the refrigerator, the radiators sighing like old men content with their memories.

Daniel’s shadow slid beneath the door to Margaret’s room. Emily pressed her palm to the paint. She heard Margaret’s voice, small and apologetic as a hymn: Danny? It’s started again. I’m sorry, love. The word sorry fell three times, like a habit Margaret couldn’t break.

Emily waited for a larger betrayal, for a sound to prove what fear wanted to prove. Instead there was the scratch of a drawer, the flick of a lamp, the uncap of a tube. Daniel’s voice, low and certain: You don’t have to be sorry, Mom. We’re okay. Then the hushed sound of gloved fingers and cotton, the ritual of care.

Emily pressed her ear to the frame and looked through the sliver the latch left. In the lamp glow she saw Daniel kneeling at the side of his mother’s bed, latex gloves pale on his hands, his face serious in the way of men measuring lumber. Margaret lay on her side, the back of her nightgown lifted to expose skin that had bloomed into a rash of furious constellations—angry red patches stippled with cracks, the kind that made a body flinch from its own surface. Daniel moved with the focus of someone building a thing no one would ever see and that mattered anyway. He dabbed and smoothed, waited, dabbed again. Margaret winced, and then breathed into the wince, and then let her shoulders fall.

The shame that followed caught Emily cleanly between the ribs. It wasn’t the shame of a woman jealous for her husband; that shame was older and she had already learned its taste. This was the shame of a counselor who had missed a symptom because love prefers prettier diagnoses.

Margaret had hid the evidence in daylight with long sleeves and sweaters soft as mercy. She smiled, and people believed the smile because believing is the fastest way to keep a conversation moving. But the flare came at night, when skin remembers everything it has ever been asked to bind up. Daniel, raised by a mother who made care into a form of weather you could depend on, answered the call the way you answer a smoke alarm.

Emily eased back from the door and stood in the hallway and let this new knowledge rearrange the furniture of her marriage. She considered that love sometimes arrives disguised as duty. She considered that sometimes duty is love stripped of the need to be witnessed. She considered that she had been alone in their bed, yes, but perhaps not abandoned.

At breakfast she poured coffee into a mug that said THIS MIGHT BE WINE in gold letters that were already beginning to scratch away, and she asked, gently, as if entering a room where someone was sleeping, What does the doctor say?

Daniel glanced at Margaret, who tightened her hand around the mug’s handle. Oh, you know doctors, Margaret said with a bright laugh that belonged to a different moment. They say things. They gave me a cream. She waved vaguely, the way women wave at problems they don’t want to fully introduce to the people they love. It’s nothing worth worrying over.

Emily nodded once, then twice, then not at all. She moved through the rest of the day with a new gravity. At school she watched a little girl carefully peel a Band‑Aid from her knee to show Emily the wound beneath. Look, the girl said, proud and frightened. It’s better and worse. Emily thought, Yes. That is exactly what truth is like.

After dismissal she drove to the pharmacy on Main where Mr. Cho stocked everything from humidifiers to hope. She stood in the aisle reading labels, the kind of reading that is really prayer. The pharmacist, a woman with silver hair braided down her back like a river, listened as Emily described what she had seen and what she hadn’t asked about until now. There are autoimmune conditions that love the night, the pharmacist explained softly. There are nerves that remember grief like an itch. Sometimes the simplest thing is the kindest—lukewarm water, fragrance‑free lotion, cotton sheets, a cool room, patience.

Emily bought lotions without promises, hydrocortisone cream, oatmeal bath packets, soft towels that would not argue with skin, cotton nightgowns. She bought peppermint tea because Margaret liked it, and a pill organizer shaped like a sun because optimism is a medicine of its own. At the register she also bought a lipstick the color of ripe cherries and felt ridiculous and also like a person who might, someday soon, step into her own life again.

That night, when the house settled and the owl asked its question from the hemlock, Emily knocked on Margaret’s door. The sound was a courtesy first, a request second. Come in, dear, Margaret said, and Emily did, carrying a basin and soft cloths the way she sometimes carried books and crayons and patience to small bodies in her office at school.

May I? she asked. May I help tonight?

Margaret’s eyes filled in a way that made the vessels look like rivers on a map. I don’t want to take your husband from you, she said in a rush, the sentence that had likely built itself quietly in her chest for months. I don’t want to be the reason you’re alone.

Emily sat on the edge of the bed, the basin warm against her shins. You’re not the reason I’m alone, she said. Pain is. And we can share that.

Daniel stood in the doorway, caught between relief and guilt like a man who has just admitted the bridge is compromised. Emily looked at him and nodded, and he nodded back—an exchange of permissions that felt almost like vows.

The first time Emily cleaned Margaret’s back, Margaret apologized six times. Each sorry was a different species: the sorry of inconvenience; the sorry of age; the sorry of asking; the sorry of being a woman in a world that thanks you most when you need least; the sorry of all the apologies you learn as a girl and can’t seem to unlearn; and the last sorry for the first sorrows you ever caused anyone at all. Emily answered each sorry with a wordless small act—wringing the cloth a little drier, adjusting the lamp, smoothing the lotion with the patience of tide. The skin calmed beneath her hands like a child lulled by the simple math of touch.

Daniel slept in their bed that night. His body, heavy with the permission to rest, yielded to the mattress. Emily lay awake a while anyway, listening to the newly unfamiliar sound of someone breathing beside her. It is a tender astonishment, the return of what you had learned to live without.

The days organized themselves into a new kindness. Daniel taught Emily the exact pressure that soothed rather than startled, the order of steps that felt like ceremony rather than triage. Emily discovered that Margaret loved stories about messy people who healed each other in small rooms—the exact kind of stories the world too often calls women’s stories as if the modifier makes them less human. Emily read aloud to her from a novel where the hero was someone’s grandmother and from a book of poems that knew the word balm in its bones.

By spring, Margaret’s skin looked less like a map of a war and more like a landscape recovering from weather. She saw a new dermatologist in Burlington who listened as if listening were an instrument she’d studied for years. There was a diagnosis with a name that sounded more complicated than the care required of them, and a plan that felt less like surrender and more like stewardship. There were new linens and a humidifier and a conversation about how to ask for what you need without apologizing first. There were small victories—nights with only one waking; mornings when the sheets were just sheets, not evidence.

The town noticed, as it does. At the market Mrs. Shipley said, You look rested, dear, as if rest were a thing you could wear like a scarf. At church, the man who had always used too firm a handshake told Daniel, Good to see you both together, son, and Daniel smiled the smile of a man who has been forgiven for a crime he never committed but still felt guilty about. On the porch, Margaret watched the bird feeder like television and learned the names of the newcomers—red‑bellied where once there’d been downy, grosbeaks where there’d been mostly chickadees. The porch itself leaned less, as if the world had remembered its center.

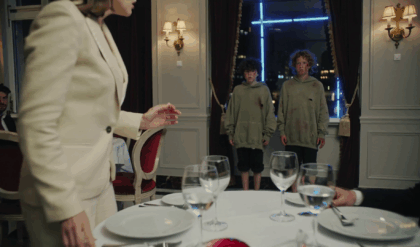

Emily and Daniel began to talk again about futures that had more than one room. They started slowly because slowly was how their trust had learned to walk. They talked about a baby in the conditional tense, the way you discuss weather in March—what if, maybe, if we’re lucky. They talked about whether the Whitaker house could hold four souls or whether it would buckle under the weight of so many histories. Daniel drew plans for an in‑law suite, a phrase Emily had once said like a joke and now pronounced like a blessing. Margaret said, I don’t want to be a burden and Emily said, You’re a person, not a bag of feed, and they laughed and cried and ordered a catalog of grab bars that were somehow beautiful.

Then life did the thing life does—it tested the new structure.

In July a thunderstorm shouldered its way over the ridge and broke open above Birch Lane. The gutters protested. The maple held the rain the way a father holds the child who ran into the street without looking—firmly, and with relief. The power blinked once and then, as if deciding to do its job after all, steadied. Daniel was out on a call for poor Mr. Perillo whose barn door had twisted itself off its hinges. Emily sat on the floor beside Margaret’s chair and painted her toenails a color called Summer Peach because small luxuries are often the only ones women will accept.

The first flash was too bright. Margaret winced, not from the light but the memory that light can be followed by pain. Then came the itch—sudden and merciless, as if rain had carried with it a message for Margaret’s skin and the message was: Remember. Emily watched the rash halo up across Margaret’s shoulders in minutes. She felt the old panic prickle the edges of her competence and she exhaled it because panic is not a tool here. She moved through the practiced steps like someone who has memorized a poem in a language she didn’t grow up speaking but now loves: cool cloths, hydrating lotion, patience. She spoke softly, told Margaret a story about a boy who had learned to breathe differently and thus learned to be himself without frightening himself. The storm kept talking. Margaret kept breathing. The body remembered how to calm down. It did.

When Daniel came home, soaked and contrite, he found his wife and mother asleep in the chair together, Emily’s head at Margaret’s shoulder, the color on Margaret’s toes shining like a small sunrise. He stood in the doorway and understood that the night had shifted from rescue to routine, from debt to devotion that moved in all directions.

Summer slid into a school year that arrived too fast, as they do, and the rhythm held. Emily discovered that she could be angry and grateful at the same time; it was not a contradiction but a chord. She was angry at the way women are asked to be endlessly accommodating, at the ways illness hides in the margins of photos and conversations, at the way her bed had been empty for so long. She was grateful for the way knowledge had made room; for the nights Daniel slept with his arm a heavy certainty across her belly; for the sound of Margaret laughing at a joke on the radio in the kitchen.

One Saturday in October they stood in a field at the apple orchard on Route 9 and watched families do the math of harvest. Emily bit into a Macintosh and the juice ran down her wrist; Daniel wiped it with his sleeve like a ceremony. Let’s try, Emily said, and Daniel’s hand trembled just enough that she felt the tremor like a benediction against her palm. They drove home with a bag of apples and a promise that felt at once fragile and inevitable.

The months that followed were not a montage—life does not respect the economy of storytelling—but they were kind. There were doctor appointments and numbers to watch and a small heartbeat on a screen that Daniel couldn’t look at directly because the glory of it made his eyes salt. There were nights when Margaret’s flare returned and Emily tended her and then padded back to bed where Daniel gathered her against him and the three of them—two skins, one heart—that night made a braid of endurance.

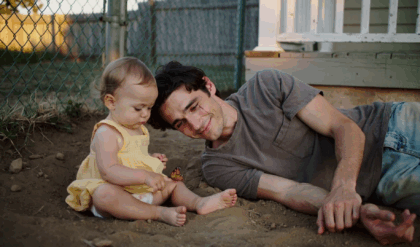

When their daughter was born in late June, a year to the week after their wedding anniversary, the hospital room held three generations of women who had learned the serious joys of care. They named her June because names are spells and sometimes you ask the calendar to bless you every year. Margaret held the baby like a secret you cannot believe you’re allowed to speak aloud. She touched June’s back with the tips of her fingers and whispered, Smooth as new paper, and Emily thought, Yes, and also: nothing stays smooth forever, and we will love her through the roughening.

The house on Birch Lane stretched somehow to hold it all. The in‑law suite took shape beneath Daniel’s measured hands and the laughter of his crew who said things like, You sure you want your mother‑in‑law this close? and then admired the way he braced a beam. Margaret moved her things into the new space with the ritual of a woman writing her life in a slightly different tense. The old master bedroom was painted a color the catalog called Quiet Lake and became a nursery where light pooled in the afternoons like a forgiving gospel.

One night, when June was four months old and the maples had begun to take the fire for themselves, Emily woke to a sound that had once meant loss and now meant family: Daniel’s feet on the floor. She glanced at the monitor; June slept with one arm thrown above her head as if answering a question in sleep. Emily listened. The steps did not go down the hall toward their old violence. They went toward the bassinet. She heard Daniel whisper the kind of words men give to tiny people when they still believe language might be a kind of magic: Hey, Junebug. You’re okay. Daddy’s here. The bed sighed when he returned and Emily exhaled a laugh she had not known she’d been holding for years.

Later that week, Margaret knocked at their door in the late evening. She had a shoebox in her hands and the face of someone about to commit a sacrament. I was going through old things, she said. I’m trying to throw away something every day. It’s a discipline. Your father never threw anything away, Daniel, remember? Receipts from 1983.

She set the box on the bed and opened it. Inside were photographs curled at the edges and a ring of keys that no longer opened anything and a slip of paper with a recipe for a lemon cake in her mother’s looping script. Margaret took a breath. I want to say something without apologizing first, she said, and Emily felt the entire house lean forward to listen. Thank you. Thank you for loving my son when he was pulled between past and present. Thank you for loving me when I was a map you had to learn to read at night. Thank you for letting this house be a place where all our odd storms could blow through without blowing us over.

Emily swallowed. She thought of how, three years ago, she had lain in a bed that felt like a field after harvest: everything gathered elsewhere. She thought of following Daniel down the hall not because she mistrusted him but because she had finally decided to trust herself. She thought of the hard grace of discovering that love doesn’t always look like you rehearsed and that sometimes what looks like betrayal is a kind of prayer.

She took Margaret’s hands and said, You’re welcome. And then, because this is what healing sounds like when it belongs to women who have done the work, she added, We did that together.

Winter returned, as it promises to in Vermont, and brought with it the quiet that makes a house creak its opinions. Daniel taught June to slap puddles in her snowsuit and to point at the moon and say the word with the roundness it deserves. Margaret’s flares came less often and with less fury; when they did, she managed them with the calm of a woman who has become an expert in herself. Emily went back to work in January and found her desk full of hand‑drawn cards from children with more empathy than grammar: We mis you Ms. Packer. Come bak to help us with our Feels.

Sometimes Emily would wake at night anyway, the old worry returning like a song stuck in the head. She would put her hand on Daniel’s chest and feel the steady beat of a man asleep in their bed. She would listen for Margaret’s soft snores through the vent, the way older houses gossip so easily. She would look at the monitor and see June, mouth open, full of the kind of trust that sleeps without bargaining. She would close her eyes and think how whole didn’t mean there were no missing pieces. It meant you loved each other across the gaps.

The shock she once feared she would one day discover turned out to be something else entirely, the sort of truth that remakes a woman quietly. It was not a betrayal. It was devotion she had not yet trained her eyes to see. It was a son doing what sons of good mothers do when grief breaks open the body in strange places. It was a mother allowing herself to be tended to in a world that praises women’s endurance more than their needs. It was a wife deciding that jealousy is the cheapest interpretation of a complicated story and that she could afford better.

Years later, when June was old enough to ask for stories from Before, Emily would tell her about the night she followed her father down the hall and learned how to be married in a house with history. She would say, I thought I wanted to be the only place he slept. I learned I wanted to be the place he rested. She would say, Your grandmother taught me that women are allowed to be tended to. She would say, Love is sometimes what you do with your hands when no one is watching. And June would listen and then demand the part about the lemon cake, because children, thank God, know how to anchor stories to dessert.

On their tenth anniversary, they took a picture on the rebuilt porch. Daniel had sawdust in his hair because there is always a project and always a reason to pause the project for a picture. Margaret stood between them with June balanced on her hip, the girl long‑limbed and gap‑toothed and certain that the world is a place that will catch her. Emily looked at the camera, then at the three people she loved from three different directions, and thought, The shocking truth is this: tenderness makes a structure strong. Everyone smiled the kind of smile that begins in the spine and moves outward. The porch light was on though the sun was still high because Margaret said it was a habit now. The light fell across their faces and made a family visible.

It is tempting to end here, to freeze the image like the cover of the life they built. But love is a practice, not a photograph. There were other storms, other flares, a teenager who slammed a door so hard a picture fell off the hallway wall, a summer when Margaret’s breath came in rattles and they learned the precise timing of inhalers and prayers, a layoff at the mill that made Daniel consider moving and then not moving, a school board meeting where Emily said the words trauma‑informed out loud four times before anyone else wanted to say them even once. There were good pears and bad peaches and the quiet holiness of people who keep showing up.

On nights when the wind wrote its fast cursive through the maples, Emily would sometimes stand in the doorway of the old bedroom where she had once stared at the ceiling and felt forsaken. The spider’s corner was empty now; even webs know when to relocate. She would remember the long early months of marriage when she mistook distance for disinterest and silence for secrets, when she had not yet learned the grammar of her husband’s loyalty. She would feel gratitude like weight and like lift. She would go back to bed. Daniel would turn toward her in his sleep and reach, his hand finding her hip as if his body were a compass that had finally learned true north. She would place her palm over his and think, This is what we made. Not a fairy tale. A shelter. Strong enough for weather.

The town kept noticing, as towns do. Mr. Perillo’s barn door held. Mrs. Shipley slipped away one December, her hand in her son’s, and left Emily her recipe for chocolate cake with a note that said, You are patient in a world that hurries. The children at school grew and some of them came back to visit with new haircuts and old manners, and one of them—who had once learned to draw his panic as a fox—gave Emily a print from his first gallery show. It was titled Night Care. In the picture, a small lamp made a circle of light around two figures, and the circle felt like a promise.

At the end of one such long, ordinary day, Emily set a lemon cake under a glass dome and wrote a note in the same words Margaret had written years earlier: Welcome home, my kids. She lit the porch light for no other reason than because she could and because someone might need to see exactly where to turn. She set her palm on the banister Daniel had smoothed a hundred times. She listened—first to the quiet, then to the small sounds of her house declaring itself alive. She felt June’s music thrumming from the room above—something teenage and large. She felt the hum of Margaret’s oxygen machine steady in the suite, the sound both mortal and miraculous. She felt Daniel’s car turn onto Birch. She lifted the cake dome and cut slices because joy is nothing if you cannot hand it to the people who taught you how to see it.

This, then, was the truth Emily had followed down a hall years ago and kept learning: love is not a secret to be discovered but a practice to be repeated. Some nights you put on gloves. Some nights you put a baby to your shoulder and hum an old song until the world is small enough to hold. Some nights you roll to the warm side of the bed and find that you are no longer alone there. And some nights, when lightning argues with the ridge and the house answers back in its sturdy timber tongue, you set a light in the window and you call that safety by its other name: home.