On winter nights at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, the hallways smelled like warm dust and ammonia, the kind of scent that made you think of late trains and missing gloves. Will Hunting pushed his mop along the corridor outside Room 2-146, where chalk turned the blackboards into galaxies. He worked the corners the way he’d learned to work every corner of his life—quick, quiet, invisible—then paused because a spray of symbols had snagged his eye. A lattice of numbers and arcs stood on the board like a locked gate, daring anyone with hands steady enough to pick it.

He told himself to keep moving. A janitor who lingers gets asked questions, and Will preferred to be a rumor that the halls dreamed up when they were bored. But something in the proof cut across his thoughts like a siren: a combinatorial graph mapped to a rigid motion, a proof-sketch dangling from a teasing “hence.” The handwriting was careful, professorial, the kind of script that expected a life of being photographed by the curious. Beneath it, in a smaller neat hand, the challenge: “To be concluded by term’s end. Recognition promised. —G.L.”

Will glanced both ways, the broom like a rifle in his fist. G.L. had to be Gerald Lambeau—the Gerald Lambeau—Fields Medal at twenty-four, tie always a little too tight for his throat. Will had seen him once through a doorway, a flock of graduate students in orbit. Lambeau was the kind of guy who made people talk about genius like it was a birthright instead of freight you carried.

Will pulled a nub of pencil from his pocket and, just for himself, traced an invisible path through the maze. The first move was obvious if you didn’t mind breaking a rule you weren’t supposed to know. The second move hid under a joke: a change of basis that looked like a sleight of hand. He smiled—couldn’t help it—then forced the mop forward and finished the floor in long, obedient strokes.

He told nobody. Not Chuckie. Not Morgan or Billy. Not the bartender who always gave him an extra inch of beer because he looked like a guy who needed it. That night, at a Southie bar where the Bud Lights were as cold as the jokes, a question kept needling him. If you solved something like that, did the room change around you? Did the roof lift, the way it did in his head? He left early without explaining, caught the T, and climbed the narrow stairs of his apartment. The heat clanked awake like an old dog. He wiped steam from his bathroom mirror with the side of his wrist, smoothed a palm across the glass until his reflection was a ghost, and began.

He liked the mirror because it took the answers without argument. A chalkboard answers you back. A mirror lets you see what you look like when you’re lying to yourself. He rewrote the boundary condition five, six, seven times, erased with his sleeve, and rewrote again. He laughed once—out loud, alone in a bathroom with peeling caulk—because a path opened that felt like finding a hidden street in a city he’d walked his whole life. For an hour he forgot to be careful. For a night he forgot to be small.

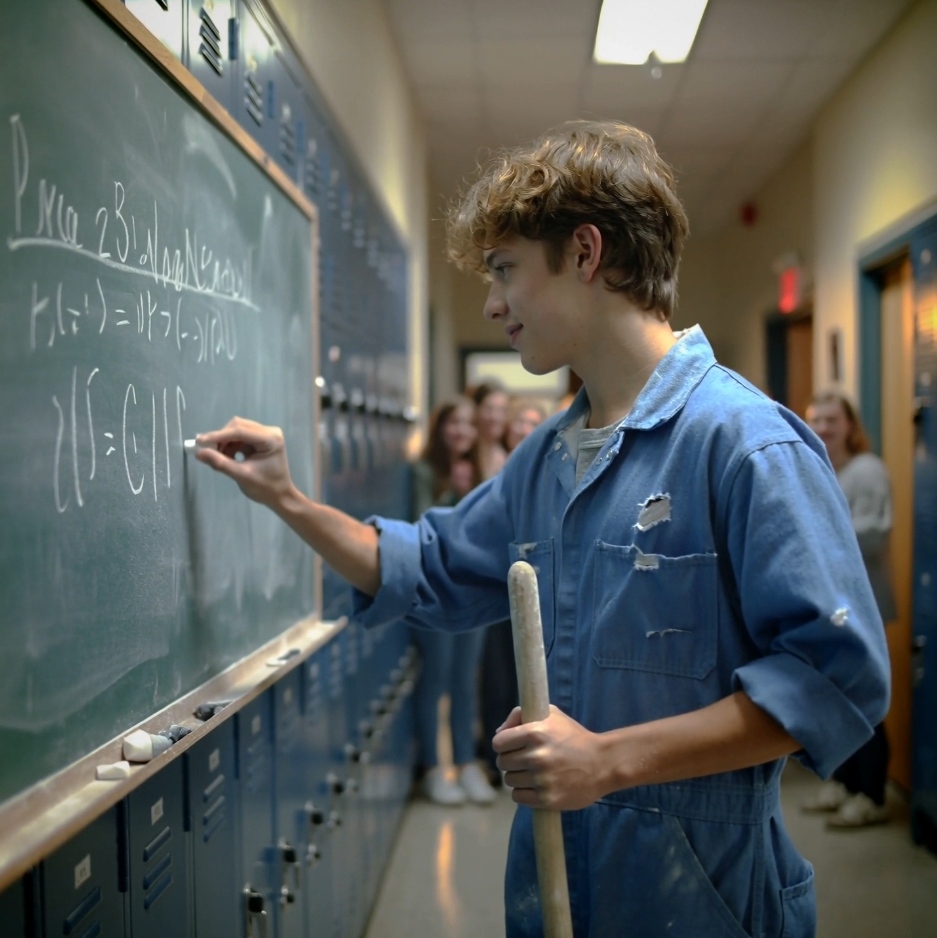

By morning, the mirror was a gray storm. He snapped a photo with a phone that held more cracked glass than battery, then showered, pulled on his work shirt, and went back to the halls that treated him like furniture. The weekend crew ran with the building’s heartbeat; Will moved between classrooms with a bucket and a hum in his head. No one watched him step toward the board. He copied two lines with the quick hand of a man writing down a license plate before it drives off, then added the hinge step. It was clean, so clean it looked like the board had been waiting for it.

From the far end of the corridor, a door slammed and a voice knifed through the fluorescent hum. “Hey—stop! Step away from that board!” Professor Gerald Lambeau, breath clouding in the draft, came into view at a run, palm up like a traffic cop.

Will heard him. He didn’t look back. He ran the last four lines in his head like a locksmith counting pins—one, two, three, and the hinge. The chalk answered with two quick squeaks as he wrote the bridging map, then a slow, deliberate underline. A small cloud of dust lifted—soft, decisive.

He set the chalk on the rail, hooked the mop bucket with his boot, and started toward the near end of the hallway, past the blue lockers and the humming vending machine. No stare‑down. No apology. He moved the way a man leaves a place that was never supposed to have his footprints.

Footfalls chased him. Lambeau blew past the last row of lockers and reached the board, reprimand ready—and then it died on his tongue. He took in the sequence; saw the change of basis hiding in plain sight, the constraint unspooled, the neat little underline like a signature refused. His mouth opened and stayed that way. “Oh my God,” he said, not to the boy already walking away, but to the work itself. A breath later, softer: “Who taught you that?”

At the far end, two grad students had stopped mid‑laugh; three undergrads hovered in the doorway, all eyes and held breath. Will’s steps receded toward the stairwell, the bucket wheels whispering. Lambeau’s finger hovered a millimeter from the solution, tracing air as if touching the proof might scare it off the slate. He stood there long enough for the dust to settle back where it came from.

On Monday, Lambeau paused in front of the board and rubbed his chin the way geniuses on magazine covers rub their chins. The class went whisper-quiet except for two undergrads in Patriots hoodies who had wandered in to skip a different lecture. “By no stretch of my imagination,” Lambeau said, “do I believe you came to hear me. You came for the magician.” He smiled a smile that belonged to someone who had just discovered there were wolves in the woods and found himself a little thrilled at being hunted.

By lunch the rumor had grown a ridiculous tail—someone started calling the mystery hand “the janitor with a 900 IQ”—a joke that stuck because nobody believed it and everybody wanted to.

When nobody spoke, he wrote a second problem. “This one took us two years,” he said, softening the boast with the plural. Two years of tenured minds in warm offices. Two years of conferences and coffee. He left the proof half-braided. The board gleamed at the seam where something difficult met something beautiful.

That night Will and his friends cut across the neighborhoods that knew their names—streets with salt on the curbs and Christmas lights still tangled in February. They passed a group of guys leaning against a smashed-in Civic, and one of the guys said something sideways to a girl, something that landed like a thrown rock. Will recognized the mouth that said it. Same mouth that used to laugh when Will’s face met a locker. He didn’t think. He told Chuckie to stop the car. He stepped out into the cold, and his fist found the past like a heat-seeking thing.

Blue lights. Hands on backs of heads. Fifty-dollar words in his mouth that he knew made cops madder, because a kid like Will wasn’t supposed to know them. In the morning, a judge read out his life like it was a list of grocery items: trespass, assault, resisting, other little fires he’d lit because you set fires when you didn’t know how to say you were scared. The courtroom was beige and bored; the Constitution sat behind the judge in a frame like a photograph of a dead relative. Will tried to talk the papers into loving him. He quoted a case he liked because it used the word “breath.” The judge listened and shook his head the way men shake their heads at weather.

From the back row, a man with too much hair sticking up watched like he’d found a message in a bottle. After the gavel fell and talking turned to shuffling, Professor Gerald Lambeau approached with his coat unbuttoned and his eyes full of a plan. By afternoon, the plan had a signature. Will would be released if he met two conditions: weekly study in Lambeau’s office and weekly therapy with a licensed clinician, reports to be filed, boxes to be checked. A leash in two parts.

Will said yes because a door had opened, and he was used to running through any door that wasn’t nailed shut.

In the televised version of genius, equations glow blue and the music swells. In Lambeau’s office, genius looked like two men standing too close to a board. Will’s handwriting went small when he was sure; it sprawled when he was guessing. Lambeau paced, clapped, pleaded, argued with the dead inside the journal articles he’d memorized. He watched Will’s mind the way some men watch a horse’s legs. Sometimes he forgot to be kind. Sometimes he was so kind Will wanted to hit him.

Therapy went worse. The first therapist stepped into the room with a book he had written about the very kind of person he thought Will was. Will took the book home, read it in a night, and returned it with page numbers circled where the man had lied without knowing he’d lied. “I can’t do this,” the man said, as if the job were balancing on a wire and someone had shaken the pole.

The second therapist tried hypnosis, and Will obliged with a story where the room’s ceiling fans turned into helicopter rotors and the room’s desk turned into a riverboat bar in Memphis. The man believed so hard it felt cruel. Will opened one eye, saw the man’s mouth forming the word “healing,” and laughed. The man flushed, and Will apologized with his eyes, which were better at apologizing than his tongue.

“Maybe,” Lambeau said, “we try someone…different.” He meant a man who had once shared a dormitory with him and had never quite forgiven him for the way the world chose favorites. Sean Maguire taught at a community college and kept his office the way people keep attics—books in leaning stacks, two chairs that had seen better days, a window grimy with honest weather. He wore his beard like he hadn’t decided whether it was armor or inertia. There was a painting on the wall of a man in a little boat on bad water.

Will sat, slouched, prepared for sparring. The first ten minutes were jokes the way some people throw hands. He went after the painting because the painting was there, said the color of the water was wrong, and the boat was sentimental. Sean listened without moving, except for one small change: the muscles in his jaw decided to wake up. When Will said the word “wife,” Sean stood. His voice went low in that way a voice goes low when it has traveled a long way to get here.

“You can talk about the boat,” he said, “but you don’t talk about her.”

Will shrugged. He had seen men who looked like murderers and turned out to be uncles. He had seen uncles who smiled and turned out to be thunderstorms. He left, and for the first time in a long time it felt like he had left a room without winning.

A week later, Sean asked him to meet by the river. They sat on a bench where thin winter last leaves fretted against a black fence. The Charles moved like a man keeping his temper. Will had jokes ready, but Sean’s voice cut across them before they were born. He told Will he had thought about him more than he’d meant to. He told him there were things you couldn’t know by memorizing—how the ceiling of the Sistine Chapel smells like plaster and old sweat, how the taste of fear sits under the tongue on your first night in a real fight, how love makes you look ridiculous and you let it because the alternative is not being alive.

“I don’t care about most of it,” Sean said. “Not because it’s not important. Because I can’t learn it from you. And you can’t learn anything from me unless you tell the truth.”

The river did what rivers do: made time look like it was going somewhere even when it wasn’t. Will said nothing for an hour. They sat like two men waiting for a storm that had the good manners to pass north.

After that, Will tried silence the way you try a haircut. He brought silence to the office and put it in the chair. Sean made tea and let it steam between them until the windows sweated. The next session, Will told a filthy joke because he had to put something in the air or choke on it. Sean laughed, shook his head. They talked about women like men do when they’re afraid to talk about anything else. Will mentioned a girl he’d met at a bar—Skylar—with a laugh like a place you could stand out of the weather. She was California in a city of February—toffee hair, eyes that made room for your face. She told him she’d inherited money and said the word the way someone says “inherit freckles.” She wanted Stanford. She wanted the idea of going somewhere where the ground under your feet never froze.

Will kissed her outside a diner under a neon sign that made everything look like a photograph. He lied to her because telling the truth felt like climbing a staircase to a door that might be locked. He said he had a dozen older brothers with names he invented and histories he embroidered. She believed him because the boy telling the story wanted it so bad you could feel the want in your teeth.

“What are you afraid of?” Sean asked.

“Ruining it,” Will said. “Right now she’s perfect.”

“Maybe you’re afraid of ruining what you think of you,” Sean said.

Will carried that sentence around like a coin in his pocket, hard and familiar. He took Skylar to the dog track, cheered like a man who had never cheered for anything that might love him back, watched the thin dogs cut arcs on brown dirt. In the bleachers he let himself look at her like she was a problem he didn’t want to solve because solving it would end the fun. She asked about his family, about where he grew up. He told another story because the first lie needed friends to keep it from getting lonely.

Word got around about his brain. Lambeau walked him into rooms where men in suits pretended not to stare at his hands like his fingers were made of keys. Someone said NSA and someone said “fast track,” and Will watched himself in the window glass like he was watching a stranger try on coats. He thought about what it looks like when a piece of information leaves a printer in a warm room and ends up making a cold thing somewhere else happen to a person whose name nobody knows. He imagined a kid turning a corner and not turning out of it. He imagined a map with places on it where the lights go out. He said no and wore the no like a jacket that fit.

Skylar, who had seen more of the world and more of her own heart than he had of his, asked him to come west. “Just say it,” she said. “Say you’ll try.” He piled reasons between them like sandbags: money, work, promises he hadn’t even made yet to people who hadn’t asked for them. She stepped around them, gentle and relentless, the way a river steps around stones until the stones aren’t there anymore. When she said “I love you,” he said nothing and everything by not believing her. When she pressed, he told her he didn’t love her and watched his own mouth deliver the line that knocked him out.

He went to work with Chuckie the next day and carried cinder blocks like they were penance. At lunch, with hands like raw meat, he said he might just keep laying brick. “You know,” he said, “shepherd a bit. Lay low.”

Chuckie looked at him the way men look at a friend who is setting a match to his own shirt. “Every day I drive by your place,” he said, “and for ten seconds I hope you’re gone. Best part of my day.” He said it like a confession, like a prayer. “You owe it to me to go. You owe it to anyone who ever loved you to be what you are.”

That night Will sat in Sean’s office and didn’t joke. Sean said Lambeau had called to yell about squandered chances. Sean said the yelling wasn’t about Will, not really—old grudges between men who had taken different turns and couldn’t forgive the versions of themselves living in each other’s heads. They drank cheap coffee like it owed them money. There was a long silence, not the kind Will had used as armor but the kind you make when you’re building a room you both want to live in.

Sean told him about his father. About a belt and a buckle. About how you learn to read footsteps on the stairs the way a sailor reads weather. Will looked at the floor because sometimes floors are easier on you than faces are. Sean said none of it was because of Will. He said it again. And again. He said it until the words wore grooves into the air and settled. Will held the edge of the chair so hard his knuckles turned the color of textbook paper. Then something inside him that had held the ceiling up for twenty years decided to set it down. It was not art. It was not clean. He cried like a kid and like a man and like both at once.

In Lambeau’s office, the chalk squeaked to sound like teeth. Will solved what was in front of him and wrote his own name small in a corner for the first time because he needed to prove to himself he could stand seeing it next to the work. Lambeau clapped him on the shoulder and said, “There it is,” like a man who had been looking for his glasses and found them on his head. They shook on a job that would make money stack in neat piles and make other men nod when he walked in.

On his birthday, his friends handed him a car made from parts that had lived other lives—a door painted the wrong blue, a fender that belonged to a story, a seat that remembered someone else’s cigarettes. They laughed because it ran. They laughed because that’s what you do at the edge of a cliff when the whole world looks like wind.

Sean came by Lambeau’s office with a peace offering that tasted like beer. He and the professor walked out into a night that was warmer than it had any right to be and decided, without ever saying it, to let the boy choose without two older men making statues of their regrets and calling it mentorship.

The next morning, Chuckie drove to Will’s like he always did before the site. He knocked. He waited. He let himself imagine California the way movies make you imagine it. He smiled at a door that didn’t open. It was the happiest he had ever been not to see his friend.

Sean found an envelope in his mailbox, the good kind with a flap that takes its time coming loose. Inside, a note in handwriting that would never be neat enough for stationers and would always be neat enough for truth. No apology. No speech. Just a line that said he was headed west because there was a girl there and he needed to find out if courage could live in a car with bad shocks. He borrowed Sean’s words, bent them a little to fit his mouth, and let them go. Sean read the note twice and then a third time without meaning to.

Will pointed the car out of Boston like a dog aiming its nose. The Pike unrolled like a dare; the toll collectors wore human faces; the radio, when it wasn’t static, was blues sung by a woman who’d earned it. He didn’t tell himself a story about destiny because all the stories he had ever told himself had been cages even when they had looked like doors. He told himself one thing: try.

He imagined Stanford the way a person imagines a word they’ve only ever read—shape without sound. He imagined seeing Skylar and having to say the kind of sentence you don’t get to rehearse. He imagined knocking and hoped, for the first time in a long time, to be afraid and do it anyway. The car’s engine murmured a rhythm he decided to believe was good luck.

Behind him, the halls at MIT still smelled like chalk and ambition. Somebody else was mopping. On Lambeau’s board, a new problem waited with its sly grin. In Sean’s office, the little painted boat on the bad water didn’t look sentimental anymore. It looked like a man who understood that sometimes the trick isn’t proving you can survive the storm; it’s proving you’re willing to leave a safe harbor for a life that might finally be yours.

In Southie, the bar poured another round for a kid who used to be mean because he was scared. Morgan told the same story worse. Billy fell in love with a waitress who could carry four pints at once and an argument longer than that. Chuckie drove to work with the window down, April cold hitting him in the face like a deal he was happy to take. He didn’t say it out loud, but inside he thanked a friend for leaving.

The highway ran out of Massachusetts and into states that sounded like weather reports. Will drove until the moon had nothing left to say and a diner, somewhere, opened just to flip on the light. He ate eggs at 3 a.m. and did the thing he had never allowed himself to do: he pictured a future that had room for his real name.

When the sun hit the windshield in a way that made everything look brand-new and kind of used, he took it as a sign. Not the kind that tells you you’re chosen. The kind that tells you you’re free. He adjusted the rearview, watched the small city of his younger self shrink in the glass, and let the rest of the country get as big as it could.

He had no idea if she would say yes when he knocked. But for the first time in forever, the not-knowing wasn’t a threat. It was a gift. Somewhere between here and there, he decided the boy who solved other people’s problems on chalkboards might be allowed to start on one of his own.

He pressed his foot, and the car answered. The road didn’t need permission to be long. He didn’t either.

The world would later tell the story as if it had been inevitable, as if a kid destined for greatness had simply found the right doors and walked through them. But the truth fit into smaller places: the fog on a bathroom mirror, the bite of cold metal on a courthouse bench, the creak of old pipes in a Southie walk-up, a sentence said on a park bench while a river pretended it was going somewhere. Will Hunting’s fame, if such a thing showed up, would be a footnote to the real fact of his life: that he stopped picking fights he could win and went looking for a fight worthy of surrender.

He drove west with both hands on the wheel, a little scared and totally alive, proving to himself with every mile that genius isn’t just what you know. Sometimes it’s what you dare to love.