Flagstaff, Arizona, woke to a sky the color of cut steel and a wind that smelled of pine and hot brakes. In the thin morning light, the mountains crouched at the edge of town like big-shouldered guardians, and the asphalt carried yesterday’s stories—black crescents where somebody had launched too hard, pale dust from far counties, the faint glitter of road salt that had wandered down from the high passes. On a corner of Route 66 where tourist buses paused for selfies and truckers took coffee by the quart, a squat cinderblock garage with peeling blue trim held itself together by the stubbornness of one man’s hands.

His name was Eli Garner. Sixty-one. Shoulders gone to rope. Beard silvered like the San Francisco Peaks in early snow. He wore an old denim shirt, sleeves rolled, and a ball cap that had been black once, the logo of a tool company faded into a shadow. Every morning at six, Eli unlocked the side door, breathed the particular incense of rubber and solvent and last night’s coffee, then ran his finger along the torque wrenches on the pegboard to make sure each one sat where it ought to. He’d replaced engines and rebuilt transmissions and tuned carburetors no one remembered how to spell, but what he loved most were the small things—lug nuts seated just so, a wheel flush against its hub, the kind of work the road itself would thank you for.

Across from the register he kept a coffee can where people tossed in screws and bolts they found in their tires. The can was mostly a joke and partly a ward against bad luck. On the shelf above it, nailed to the wall with a single roofing nail, hung a small, weirdly moving thing: a broken wheel stud—steel shank snapped dead in the middle—cast in a cheap epoxy and fitted with a brass ring. A keychain. Eli had made it twenty years ago after a tourist from Ohio limped in on three lug nuts and a prayer. He’d saved her that day. After, he had picked up the broken stud from the cracked concrete and poured resin around it at the kitchen table while his daughter, Nora, did her spelling list. The keychain wasn’t pretty. But he kept it where he could see it because it reminded him that what fails teaches, and what teaches can be carried.

On the morning it all began, Eli was on his knees in bay two, listening with his fingertips. A white Tacoma had a harmonic in the front end, a hum like a fly trapped in a jar when the speed crossed forty. He spun the wheel and watched the tire drift outward at the slightest high spot. Runout. He’d measure it in a minute with the dial indicator and then decide if the rim could be trued or if the customer needed to know a new wheel would save him a hundred dollars of tire in the next six months. He was thinking about that math when the garage door rattled.

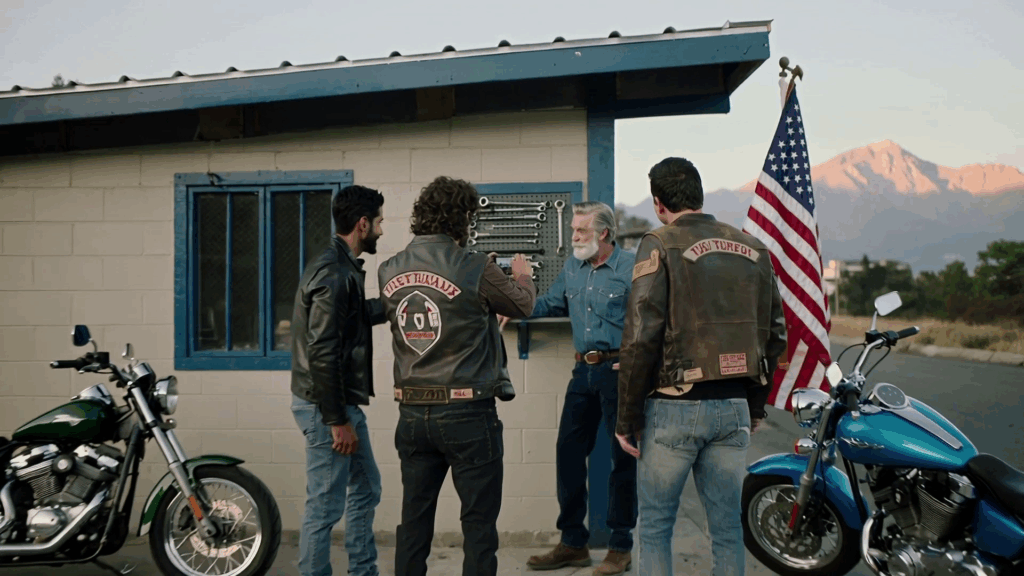

They rolled in louder than the door could contend with. Four bikes first, then a fifth, all brothers in chrome and matte, pipe heat iridescing in the morning. The lead guy—thick neck, T-shirt cut off at the sleeves, a smile like a scratch—killed his engine and let the bike tell the last of the story. The jacket patch was local. Mogollon Ridge Riders. Most of them were decent boys who wanted to feel the road climb into their bones, but this bunch had decided the internet made you tall.

“Morning,” Eli said, wiping his palms on a rag. “What can I do for you gentlemen?”

The lead rider swung a leg off and rolled his shoulders like he was about to throw a pitch. “We got a wobble,” he said. “Front end shakes on decel. You know, old man, maybe check if you put the wheels on right.” His friends laughed too quickly. One of them had a phone out, already filming.

Eli stood, the bones in his knees clicking like old relays. “You ride hard on those canyon roads, you’ll cup a tire,” he said, gentle, factual. “Let’s take a look.”

He rolled the first bike onto the lift and spun the wheel. The tread was scalloped in waves, consistent with hard braking on a bike that saw more throttle than therapy. He pointed and explained, the way he always did, the way he would have to a kid or a visiting professor. He talked about contact patch and wear patterns and the importance of torquing the axle pinch bolts evenly in sequence so the forks didn’t twist and bind. He reached for his torque wrench, set it by feel, then checked the setting with his eyes because hands lied sometimes.

“See,” he said, tightening in a slow, even star across the front wheel fasteners, “you don’t crank one side and then the other. You go in pattern so you seat it true.”

The lead rider glanced at the phone. “Pattern,” he said, tasting the word like it didn’t belong to Eli. “Hey, grandpa, show the internet your pattern.”

Eli ignored the dig. He finished the sequence, bounced the front end, loosened and re-torqued the pinch bolts to let the forks settle neutral. The shake would never vanish with a tire that far gone, but it would soften. He told the rider the truth. “You’ll need a new tire,” he said. “And next time, don’t slam her so hard into the grade. Treat those brakes like a parachute, not a fist.”

“Got it,” the rider said loudly for the camera, lifting his voice to mock instruction. “Use a parachute, kids.” He flashed a grin like a dare and peeled a hundred from his wallet. “This enough for grandpa’s coffee?”

Eli shook his head. “Forty will cover the adjustment,” he said. He wrote the receipt in his slow block letters, showed the man where he’d noted the tire’s condition, then put the wrench back where it lived.

He didn’t see the video until lunch. Nora texted him a link with a question mark. Eli clicked and watched himself move inside someone else’s narrative. The clip was cut to make him look lost. The young man had filmed over Eli’s explanations with a warbling song and subtitles: OLD MAN CAN’T TORQUE A LUG TO SAVE HIS LIFE. They’d slowed his movements and captioned them with laugh emojis. The part where he explained the star pattern was clipped so it looked like he didn’t know which bolt to pick next. A jump cut took a quiet, careful pause and turned it into a shiver. The video ended with the hundred held up like a trophy and someone off-screen saying, “You sure you know what you’re doing, pops?”

By two o’clock, his business page on the maps app had a new constellation of one-star reviews from four states away. Eli read them like he was studying misfires. “Left my wheel loose—almost died.” “Doesn’t even know torque specs.” “Genuine hazard.” Names he’d never seen. Profiles with no photos. The algorithm did not ask if his hands were steady; it did not consider that he had an ASE certification dated back when torque specs lived in paper manuals under greasy clipboards. It did not know that for legal reasons he made every customer sign a simple liability waiver before service—a sentence and a half that had saved him once when a kid had ignored a warning about cheap studs.

The phone went quiet. Walk-ins didn’t walk in. By four, the shadow of the Peaks had reached across the lot and into bay three where the old alignment rack sat idle like a ship in dry dock. Eli stood with the silence and felt something inside him suspend. You can’t fix road noise with silence.

Nora came by after closing. She was lean like her mother had been, the kind of woman who could pick up a transmission with the help of a hoist and an old joke. She ran a small coffee roastery on the south side and on weekends she brought pastries and pretended he needed them. She looked at him now, then at the empty rack of work orders. “Dad,” she said.

“Some boys took a funny video,” Eli said. “And the world decided it was true.”

“I flagged them,” she said softly. “But flags are small.” She hesitated. “There’s someone I think you should meet.”

“Who?”

“A friend of mine from the gym. She’s with the Arizona DOT, commercial vehicle enforcement. She knows more about axle loads than anyone I’ve ever met. She saw the video and she said—well, she had opinions.”

Eli folded the rag tighter than it needed to be folded. “I know how to torque a lug,” he said, and surprised himself with the salt in his voice.

“I know,” Nora said. “But maybe let her come by anyway. If not for you, then for me. It will feel like we’re saying something back.”

He looked at the keychain on the wall. The little broken stud winked in the failing light like it had something to add. “Okay,” Eli said.

Her name was Renee Park, and she arrived the next morning in a Tahoe with the state crest on the door, a binder fat with forms in the passenger seat, and a torque wrench case that could have been a cello if you had lived a stranger life. She had dark hair pulled back in a low braid and sunglasses that did not announce themselves. She stuck out a hand and shook Eli’s like she was waking up an old friend.

“I’m here unofficially,” she said first, like a preface. “So nobody’s getting cited. This is coffee and conversation.”

“Coffee I have,” Eli said, and poured into paper cups because the mugs were from another era and he’d gotten too careful.

Renee walked the shop the way an inspector does—observing without making it feel like observation. She ran a finger along the calibration stickers on the torque wrenches, checked the dates, nodded when she saw they were within twelve months. She looked at the dial indicator, at the wheel balancer, at the plug-patch tire repair kit he kept locked because shortcuts tempted even honest men.

“You been doing this how long?” she asked finally.

“Since before the interstate figured out what it wanted to be,” Eli said. “I’ve got ASE on the wall there, though the paper fades faster than the habit.”

Renee smiled. “ASE lasts,” she said. “People forget, but the bolts don’t.” She put her coffee down. “Let me show you a thing or two I show rookies. Not because you don’t know—consider it a different angle.”

She popped open the long case and lifted out a torque wrench with a head like a knuckle. “Click-type,” she said. “Electronic are nice, but these teach your hand.” She set it to a number and had him watch her check it against a calibration block she’d brought—an odd little device that measured applied torque. The click came steady at spec. “Torque is just a promise,” she said. “You promise a fastener a certain twist, and then you keep your word.”

They moved to a Ford F-150 with a slight shimmy, a regular’s truck he’d asked to come by. Renee took off a wheel and went to the hub. “You know about patterns,” she said, glancing up at him with a flicker that might have been humor. “Star, across, never clockwise around the circle. But most folks forget the why.” She explained: how even seating prevents a wheel from cocking, how a cocked wheel leads to eccentric load, how one side fights the other until heat builds, studs stretch, and the road keeps the score.

She had him watch as she used a dial indicator to measure lateral and radial runout, the needle flickering like a pulse. “You write down the thousandths,” she said. “And then you locate the high spot and you mark it. You rotate the tire on the rim to offset the high spot if the tire’s the problem. If it’s the wheel, you decide if it’s worth a press or a replacement.” Her hands were clean, precise. She talked about the DOT tables for axle loads and how under-inflation on duals shunts weight to the mate tire until one does the job of two and dies for both.

Eli found himself listening the way a young man listens. Not because he didn’t know, but because there are ways of knowing that make you young again. He would not say that out loud. He would nod and say “Right,” and then ask a small question that would earn him a small answer, and by the time the coffee went cold, he would have in his mind a new map of an old country.

They patched a tire the right way—not a string jammed into a wound, but a mushroom-shaped plug-patch, stem through the injury, patch flush against the interior, cured and trimmed and balanced. They weighed the wheel, added and moved weights until it sang true. They torqued the lugs in a star, first with the wrench set low, then again at full spec, and then again after the truck had been set down and had taken a breath.

“Something else,” Renee said, closing the case. “People don’t see the work when it’s quiet. So you show them. Put up a little sign: ‘Torque pattern followed; studs inspected; wheel runout measured to under five thousandths; plug-patch repair per RMA guidelines.’ That’s not for the yahoos with cameras. That’s for the people who want the story told right.”

Eli liked the way the word guidelines felt beside the grease. “I’ll make a sign,” he said. “I’ll even spell it right.”

She looked at the video thumbnail on the cracked office screen, the still frame with his hands frozen mid-air. “You want my opinion? Don’t answer them there,” she said. “Answer them out here. On the asphalt.”

“How?”

“By being the guy who doesn’t let wheels come off.”

For a week, Flagstaff pretended not to notice him while it watched his reviews sink. Eli kept his head down and worked the few jobs that came, then filled the empty hours with calibration and cleaning and making the sign. He used Nora’s laser printer and a thrift-store frame and put the sign by the register where the credit-card reader had to look at it before it judged him.

He started a ritual. Every car that rolled out of his bays, he took a photograph of the torque wrench with the date and the spec card in frame. He filed the photos by plate number and kept the records on paper too because paper forgives when computers don’t. It wasn’t court, but it was close enough for a man who believed that the world tilted toward the documented.

Then the mountain decided to throw weather.

On a Friday when the wind kept changing its mind, a call came in from a number he recognized by the way his stomach tightened. It was Station 3, Coconino County. He had rotated and balanced their brush truck last summer and they still owed him for the second hose reel he’d fixed with bailing wire and faith. The dispatcher didn’t waste vowels.

“Garner’s?”

“This is Eli.”

“You got a minute?”

“I’ve got as many as you need.”

“We’ve got an ambulance convoy stuck on the switchbacks up past Oak Creek. They’re headed north out of Sedona, bringing a burn patient to FMC. One rig’s bouncing so bad they can’t risk the speed they need. Our guy says it’s a front-end wobble like a carnival ride. You available?”

“Do they have a turn-out big enough for me to set up?”

“Not really.”

“Then tell them to crawl to that scenic pull-off at mile marker fourteen. I’ll meet them with what I can carry.”

He grabbed his traveling kit—torque wrenches, dial indicator, breaker bar, plugs, patches, air tank, jack, blocks, granite-still calm—and he grabbed the keychain from the wall without quite knowing why. He slid it into his pocket and felt the weight of an old failure turned into a reminder.

Nora beat him to the door. “I’ll drive,” she said, keys in hand.

They hit 89A and climbed, the road switching and backing on itself like a snake trying to tie a knot. The pines leaned in. Red rock glowed like embers banked under ash. Halfway up, he saw the convoy: two ambulances, lights cold in daylight, a fire command pickup behind them, and a highway patrol cruiser blocking southbound with a hand up to wave them through. One of the ambulances was bleeding motion—vibrating at idle the way a washing machine does when it’s swallowed a boot.

Eli stepped out into wind that tasted like rain coming. The paramedic captain, a woman with freckled arms and a jaw you trusted, met him at the front of the shaking rig. “We’ve got a twelve-year-old in there,” she said in the kind of voice that lives right behind the sternum. “Burns. We need to make time and we can’t with this wobble. I can’t risk a blowout on the grades.”

Eli squatted by the wheel and put a gloved hand on the tread. He felt the scalloping, the memory of too many hard corners. He checked the lugs with a quick bar pull—tight enough. He nodded toward the jack points. “I’m going to lift her and spin the wheel,” he said. “We’ll see the story.”

They blocked the back wheels and jacked the front a hair, just enough to ease the weight off. Eli set the dial indicator against the rim, the little needle trembling with the wind. He spun. The needle swung out and back. Fourteen thousandths. Too much for a rig that carried lives. He looked at the hub face and the wheel mating surface. Fine dust had crusted on the hub, microscopic grit that can hold a wheel off just enough to make a liar out of your torque. He scraped it clean with a brass brush Renee would have approved of, cleaned the wheel face, rotated the tire on the rim one lug over to offset the high spot, re-seated it. Then he torqued in a star: two passes, then a drop, then a check. He set the runout again. The needle swung less now. Five thousandths. It would do.

“Take it twenty yards and back,” he said to the driver. “Don’t talk to her, listen to her.”

The ambulance eased forward, turned in a slow arc, came back and rested. The vibration had dropped to something that lived in the dashboard instead of under your bones.

The paramedic captain exhaled like she’d been holding her breath since Sedona. “Can you do the other side?” she asked.

“I can do both axles if you give me ten minutes and that firefighter’s hands,” Eli said, nodding at a young man standing ready by the gear. The kid was strong and careful and learned fast. They torqued and spun and measured. A trooper held southbound traffic like the mountain itself had given him permission to boss it around. When they were done, the rig sat quiet enough to listen to the patient breathe.

The captain squeezed Eli’s shoulder. It was not gratitude so much as recognition. “We’ll send something for your wall,” she said. “It won’t be money.”

“I’ve got a wall,” Eli said, and patted the pocket where the keychain rested.

They cleared the road. The convoy’s lights came on, and even in the day, even without sirens, they looked like hope moving. The rigs gathered themselves and launched, the grade taking them, the mountain making room. Nora watched them go, eyes wet with the kind that swells you without drowning you.

On the drive down, Eli said, “I used a pattern I learned.”

“From whom?” Nora asked, but she was smiling.

“A friend,” he said.

Monday, there was a letter on his mat. Thick paper, the kind that knows its own weight. The Coconino County Fire Chief thanked him, in ink that had not been printed, for the help rendered on a roadside pull-off at mile marker fourteen. The letter did not mention torque specs or star patterns or thousandths of runout. It mentioned a child’s name and the words “made possible.” He framed it and set it next to the sign he’d made and said nothing about either to anyone.

But Flagstaff notices things. Customers trickled back. A rancher who’d always done his own work but who didn’t like the way the world had gotten said, “Figure I’ll let you balance that dually set. My eyes ain’t what they were.” A mountain guide brought in a fleet of dusty Subarus and turned a keychain in his fingers while she waited. “What’s that?” she asked, pointing to the resin block on the wall.

“A lesson,” Eli said. “I kept it so I wouldn’t forget.”

By the end of the week, the Mogollon Ridge Riders rolled up again. Five of them, same pipes, same posture, the lead guy’s smile a little more careful now. He took off his helmet and held it under his arm like it was a question.

“Your video did numbers,” Eli said, not unkindly.

“Yeah,” the lead rider said, wincing because there were costs he hadn’t done the math on. “Hey, look, we—uh—we heard you helped those ambulances. My cousin’s with Station 3. Said you saved them ten minutes and maybe a life.”

“I did my job,” Eli said. “What do you need today?”

The rider glanced at his front tire. “Truth? I need new rubber. And I need you to show me the thing with the forks again. I been thinking about it.”

Eli looked at him a long second that was longer than it had to be and then nodded. “Roll her in,” he said. “And leave the camera on the seat.”

They worked in a rhythm that felt almost like forgiveness. Eli explained again the why of the pattern, the why of loosening and re-torquing pinch bolts, the why of balance. The rider listened like a man trying to grow into a larger idea of himself. When they were done, he laid cash on the counter and looked at the keychain on the wall.

“What’s that?” he asked, because some questions are the toll you pay to cross a bridge.

“A promise I broke once,” Eli said. “And a promise I keep now.”

The rider nodded like he recognized the architecture of that answer from somewhere in his own bones.

Two weeks later, the city posted the RFP for the fire department’s maintenance contract—rotations, balances, tire service, the whole wheelhouse for the rigs that ran toward other people’s worst nights. It was not a lot of money by city standards, but it was a lot for a single-bay corner shop. Eli read the document at his counter while a pot of coffee took too long to think, and he felt a nervousness that tasted like youth under his tongue.

“You should bid,” Nora said. “You’ll beat the chain shops on quality and the fleet guys on heart.”

“I’ll need a second torque wrench if I win,” he said, and then realized that was a way of saying he believed it was possible. “And a mobile jack with more grace than mine.”

They put the bid together at the roastery after closing, the smell of beans and paper and ink mixing like it was a thing somebody had invented on purpose. Eli wrote the part about procedures himself. He talked about torque patterns and runout tolerances and plug-patch repairs per Rubber Manufacturers Association guidelines. He wrote two sentences a lawyer would have smiled at: that he maintained current ASE certifications applicable to wheel and tire service; that he required a standard liability waiver for private customers—not as a shield for negligence but as a clear-eyed agreement about risks everybody pretended not to see until they were standing on the side of the interstate looking at a shredded tread.

They printed the pages, slid them into a binder, and turned it in a day early because some rituals matter.

Word travels in towns like Flagstaff the way wind does—around corners, over roofs, into the places you thought were sealed. The Ridge Riders heard he’d bid. Competition did its usual math and came up with the old solution: if you can’t out-earn a man, un-earn him. Comments started appearing again under the old video. New ones too, filmed more cleverly, framed to humiliate without saying the word. One night, somebody chalked on his bay door a drawing of a lug nut crossed out by a big X. It washed off in the morning, easy as a bad idea, but it left a fog behind it that soap couldn’t reach.

“Let them talk,” Renee said when he called. “Show up to the evaluation with your tools, not your feelings.”

“I’m bringing both,” Eli said, and she laughed, which loosened something that had tightened around his lungs.

The evaluation happened at Station 1, under the big flag that never quite stopped moving. Three shops had made the shortlist: a national chain with matching polo shirts and a brochure that looked expensive; a fleet service company out of Phoenix with a truck that could lift a city bus; and Eli, who showed up in his faded cap with a torque wrench in a case and a dial indicator in a plastic box that used to hold cookies.

A committee sat at a folding table: the Fire Chief, the city procurement officer, two captains, and—Eli felt the surprise hit his chest and then settle—Renee, in a different blazer, here as a subject-matter consultant. She did not smile at him and he did not expect her to. The rules were the rules. The lead evaluator explained the test: demonstrate procedures for diagnosing and correcting a front-end vibration on Ambulance 2; show repair protocols for a punctured tire on a brush truck; present documentation practices for torque and runout; answer questions about response capability for roadside assistance on mountain grades.

The national chain went first. They were efficient and loud. They had torque wrenches that beeped and printers that printed. They held the tools like props, the way a magician does, hoping the patter would fill the silence any good work makes. They passed, technically. The fleet company went second. Their truck could have serviced a plane. They could respond fast. Their hands were good. Their forms were better. They passed and impressed and left behind the smell of diesel confidence.

Eli stepped up third. He set the dial indicator and spun the wheel and the needle spoke to him. He scraped the hub face with a brass brush and the Chief leaned in, curious. “Why the brush?”

“Because a speck is a liar,” Eli said. “And a liar at the hub makes a liar out of torque.” He seated the wheel, torqued in star, set her down, re-torqued. He explained why he didn’t trust plug-only repairs and how plug-patches turned a wound into a scar that would hold. He showed his log: photographs for each job, spec sheets attached, torque values noted with his initials and the time. He did not hurry. He did not elaborate. He let the work be understandable in its own native language.

They asked the question you always hope they’ll ask: “If somebody posts a video of you doing this and cuts it to make you look like you don’t know what you’re doing, what will you do?” It was the procurement officer, who had the internet’s tiredness around his eyes.

“I’ll keep doing it,” Eli said. “And I’ll invite them to watch longer.”

He could feel someone behind him shift, a small creak like a floorboard. He didn’t turn. He knew a certain kind of attention when it bent toward him.

The Chief thanked him. The committee conferred. The chain store manager pressed his lips thin. The fleet company rep checked his watch. The door at the back of the apparatus bay opened, and between slats of light stepped three of the Mogollon Ridge Riders and a man with a phone who had not learned a new trick in a long time.

“Excuse me,” one of the captains said, stepping forward. “We’re in closed session.”

“Public building,” the phone man said. “Public bidding. Public’s got a right to record.” The Riders behind him smirked—the old, easy smirk of boys who never had to grow up because the internet kept filling their refrigerators with attention.

The Chief was calm. “Public has a right to be outside,” she said. “Inside is for the work.”

“Hey, Chief,” the lead Rider called, loud enough to ricochet, “you know that guy left a wheel loose on my cousin’s car? Almost killed him. Look it up.” He jerked his chin at Eli. “Old-timer here can’t find a star unless it’s in a Christmas play.”

The room held its breath. Renee stood, clip-boarded, professional. “Captain,” she said to the man beside her. “Would you mind?”

The captain crossed the bay with a steadiness that made the phone man backpedal instinctively. “You’re done,” the captain said. “If you’re still filming, stop. If you’re still talking, stop. We’re working.” The Riders looked at each other, a little lost, the way dogs do when their pack leader forgets the next command. They hesitated too long. Two firefighters stepped kindly into the gap and moved them out in a way that was half courtesy, half map.

The Chief looked at Eli. “I’ve got what I need,” she said. Her voice had the same behind-the-sternum pitch he’d heard on the mountain road. “We’ll notify all bidders by end of week.”

Eli nodded. “Thank you for the time.” He packed the dial indicator, the torque wrench. As he snapped the case shut, the broken stud in his pocket—he’d carried the keychain today without meaning to—pressed against his leg as if to say a thing he hadn’t yet put into words.

They called on Wednesday. Procurement’s email was formal and exact, numbers and points and the kind of words that keep mayors from calling you later. But the last line of the Fire Chief’s attached letter was not. It said: We prefer vendors who torque their promises.

Eli sat at his counter with the letter open and the shop door propped to catch the afternoon, and for a full minute he did not move. When he finally stood, he took down the keychain and set it on the counter like a paperweight for a wind that had stopped. Nora walked in on him staring at it and put her hand on his back between the shoulders, a place where once a very small girl had buried a face to hide from thunder.

“What now?” she asked.

“Now I make sure the winning means something beyond a line on the ledger,” he said. He opened the bid packet he had submitted and wrote with a pen in the margin under “Contract Terms, Additional Notes.” He wrote: I will accept award contingent on inclusion of a no-cost training clause—quarterly workshops open to small independent garages within Coconino County on proper wheel service, torque patterns, runout measurement, and RMA-compliant plug-patch repairs. He initialed it. He scanned and sent it back. The phone chimed five minutes later with the Chief’s reply: Agreed.

Nora read over his shoulder. “You’re giving it away,” she said, proud and worried in equal measure.

“I’m multiplying it,” he said. “If more rigs roll out right because a kid in a mom-and-pop learned to set a dial indicator, that’s a win I can’t balance in my books anyway.”

The first workshop happened on a Saturday that smelled like rain finally delivering on its threats. Four small shops sent techs: a father-and-son garage out by Bellemont, a woman who ran a tire bay in Page Springs, a kid who’d just bought a Harbor Freight torque wrench and tattoos of socket sizes, and a guy whose hands were too clean because the chain shop had kept him writing estimates instead of turning wrenches. They stood around bay two and listened to Eli and Renee—who had agreed to co-teach because the rules of her heart allowed it on her own time—walk through the whole ritual.

Renee talked liability and documentation with a brisk clarity that made pens hurry across paper. She explained that a signed waiver did not absolve negligence but did clarify responsibilities and usefully documented that torque values had been applied and checked. She showed how to log a torque check after twenty-five to fifty miles for certain vehicles with new studs. Eli demonstrated the star pattern and made people say the why out loud. He ran the dial indicator and made them read the needle and then choose their own threshold for when to replace a wheel because numbers without judgment are just fancy dice.

Between sessions he passed around the keychain. “Carry your broken things,” he said. “Make them into something you can touch. Don’t forget the day you learned what you didn’t know.” He watched the way their fingers closed around the little weight. He saw the look that meant something had landed.

Outside, a bike pulled up. He recognized the sound before he recognized the face. The lead Rider from the video took off his helmet and tried to find a way to stand in the doorway that didn’t feel like a trespass.

“You here to heckle or learn?” Eli asked.

The man swallowed, Adam’s apple hopping like a frog. “Learn,” he said. “If you’ll let me.”

Eli glanced at the group. No one flinched. “Grab a notepad,” he said. “And if you film anything, make it boring.”

“Boring,” the man said. “Got it.”

He didn’t film. He listened. He asked a good question about spoke tension on an older wheel set and how that could mimic a balance issue. Renee answered with a short lecture on vector forces that made the kid with the tattoo grin like he’d found a new language he could write on skin.

At lunch, the Rider stood by the counter and touched the keychain like he was reading Braille. “You going to sell those?” he asked, trying for light.

“No,” Eli said. “You can make your own.”

“How?”

“Go where you failed,” Eli said. “Pick something up. Pour resin around it. Carry it till it’s heavier than it is.”

The man nodded, which is a way of bowing without admitting you’re bowing.

Fall slid toward winter. The Peaks put on their hats and the air at dawn got a lid on it. The ambulances came in on schedule for checks. Eli took his photographs with the torque wrench and the spec card, printed them, filed them. He went on three roadside calls himself because certain jobs belong to the person whose name is on the sign even if only birds read the sign on cold nights. He stood in sleet once on I-40 with the wind punching him in the side and torqued a pattern by touch while a firefighter held an umbrella that flipped inside out and laughed like this was the cost of admission.

The video still existed. The comments still breathed. But the town had decided something in its own bones, and the town is a jury no court can overrule. People nodded at him at the grocery store. A state trooper paid for his coffee at Miz Zip’s without saying a word. Renee stopped by with a new calibration sticker and a story about a weigh station where a driver had argued axle load like it was political philosophy until the scale taught him physics.

One evening, Nora found him at the workbench casting resin. “What’s the project?” she asked.

He held up a small mold. Inside sat a sheared-off lug nut from the brush truck, sacrificed in a training demonstration to show what over-torque can do. “Thought the Chief might like a paperweight,” he said. “Something to hold down procurement’s paperwork when the wind kicks up.”

“Looks like a keychain to me,” she said.

He shrugged. “Maybe she’ll put her station keys on it. Maybe she’ll throw it in a drawer. Either way, it’ll be there. Heavier than it is.”

He poured the resin, watched it creep around the metal, the way new ideas creep around old habits until they hold.

On a cold, bright morning that cracked like ice underboot, he delivered the paperweight to Station 1 with a note: For the desk that signs the work nobody sees. The Chief laughed when she saw it, then got quiet. “We carry our broken things,” she said, more to herself than to him. “I like that.” She looked up. “You free this afternoon? We’re running a drill up on Snowbowl Road. Could use someone who believes in patterns.”

He went. He brought his tools. He watched the rigs snake up the grade, lights off because drills don’t need the same kind of hope. He stood at the turnout after and looked down at the tire tracks striped on clean snow where they had braked and turned and backed like a dance. The tracks were crisp, each block defined, no feathering, no chatter. He thought of the day on the mountain, the wind, the dial indicator, the runout needle steadying under his hand.

Nora stood beside him and hooked her arm through his like she used to do when she was small and the world was too tall. “What are you thinking?” she asked.

“That torque is a promise,” he said. “And promises are heavier here.”

They watched as the last ambulance rolled down, quiet as a held breath. Somewhere lower on the mountain, a pair of taillights turned into the highway and poured themselves into the distance. Eli imagined the glow as it went: red, then less red, then only the knowledge of red, which is to say the memory of someone else’s burden moving away from you and toward the place where help lives.

He took the keychain from his pocket and weighed it in his palm. It was small. It was ridiculous. It was perfect. He closed his fingers around it and felt the cool of the resin warm. He thought of the biker on his worst day and his better one, of Renee teaching him a thing he already knew fenced in by a fence he hadn’t seen, of the Chief writing letters, of Nora filling the shop with laughter on days when there wasn’t enough work to fill it with anything else.

“We going home?” Nora asked.

“In a minute,” he said.

They stood there while the mountain breathed. When they finally walked back to the truck, their boots left prints that looked like they’d been placed with care. On the road below, the faintest streak of rubber curved cleanly across the asphalt where a driver had braked just right at just the right moment, leaving behind not a scar but a signature.

And somewhere, far down the grade, under a sky that had decided to be kind, the echo of ambulance LEDs pulsed and then softened and then disappeared into the kind of ordinary afternoon you only get after somebody has done their job exactly, invisibly right.

The contract didn’t change the way the mornings smelled. Rubber. Coffee. Cold air that kept its edge even when the sun came up. What it changed was the way people arrived. Engines cut a little earlier. Doors opened a little slower. Folks came into Eli Garner’s shop like they knew the work inside could slip a life into somebody’s pocket later when the day asked for it.

By the second week, Station 3’s rigs had a rhythm on the rack. Ambulance 2 liked to squeak her rear shocks when the air got dry. The brush truck carried a ghost vibration that only showed up under load—an echo from the water tank baffling like a belly laugh in the wrong place. Eli logged, torqued, checked, re-checked. He kept the photographs with the wrench and the spec cards. He kept the old habits and let the new ones braid through them until he could not tell which had grown from which.

Renee came by with a list and the kind of smile that says the list is better than it looks. “State’s doing a winter-readiness push,” she said, tapping the clipboard. “We’re rolling through the passes next Wednesday with DPS. Chain checks. Axle load compliance. You want to tag along, unofficial? Extra hands for quick turn torque checks. You’ll see some things you can’t unsee.”

Eli laughed. “That’s how I know I’m still breathing.”

They did the shifts up near Snowbowl the way you run a lighthouse—steady, repetitive acts that keep catastrophe boring. A rental SUV rolled up with tires so bald he could read his name in their reflection. A delivery box truck squatted like a tired dog, underinflated inner duals flapping like tongues. Renee worked the scales like a conductor, sending some through, sending others to the side, all with a firm calm that carried no apology because gravity doesn’t negotiate.

At midday, a familiar face lifted a visor at the checkpoint. The lead Rider. His breath fogged the air. His eyes didn’t flit to the camera because there wasn’t one in his hand. The bike wore new rubber like a man wears a suit to court—conscious of it in every step.

“Morning,” he said to Eli, as if addressing the weather. “Torque check?”

Eli nodded. “Cold shrinks. Good to re-check,” he said. The wrench clicked across the star on the front. Click, click, click, a metronome for humility. He set down the wrench and rested a palm lightly on the tire as if feeling for a fever. “How’s she feel on decel?” he asked.

“Straight,” the Rider said. “Like a promise.” He looked at Renee. “You the one who showed him the calibration block?”

Renee lifted one corner of her mouth. “I showed him my way. He showed me his.”

The Rider gave a conservative nod—the kind men give when they are not practiced at gratitude, then rolled away with a throttle that didn’t need to prove anything.

The trouble didn’t arrive like trouble. It came as a call from Procurement, neutral as a judge’s robe. “We’ve received a complaint,” the officer said. “Alleging improper torque procedures on Brush 5 last Tuesday. Public records request will pull this into daylight, so I wanted you to hear it from me. We’ll need your logs.”

Eli’s breath didn’t change. He reached for the binder. “You’ll have photographs attached to the work order,” he said. “Torque spec: 165 lb-ft, two-pass star with post-settle check at ground. Runout recorded at three thousandths radial, four lateral. We advised re-check at 50 miles; signed by Captain Ames when she brought it by after the drill. You’ve got her signature on the page. I can email a scan in five minutes.”

The officer cleared his throat. “That will be sufficient.” A beat. “For the record, this is the stupidest complaint I’ve read this quarter.”

When the complaint hit the city website, it already had a counterweight. The Fire Chief’s office posted Eli’s documentation right beside it, the way a good mechanic lays out the worn part and the new one side by side. Someone in the comments tried for a kick—“Photos can be faked”—and the Fire Chief replied, “So can opinions.” The thing about a town that had decided to trust its own eyes is that it knew where to put its feet.

Nora watched the online dust-up on her phone behind the roastery counter and exhaled like a bellows. “Every time I think they’re done,” she muttered. “They find a fresh angle.”

“Angles are what you need to seat a wheel,” Eli said, passing through with a box of valve stems. “Let ‘em turn. We’ll torque it.”

Saturday’s workshop filled up, then overflowed. Renee claimed a whiteboard someone had retired from teaching calculus and drew triangles that turned into vectors that turned into a diagonal truth about clamping force. Eli handed out a half-sheet he’d typed on his old computer: WHEEL SERVICE PROMISES. He’d numbered them one to seven and laughed to himself that he’d ended up with seven even though he hadn’t been aiming for a number that tidy.

-

Clean mating surfaces. Brass brush. No exceptions.

Hand-start lugs. The first turn is feel. The second is evidence.

Star pattern always. Across, not around. Even seating or it’s all lies.

Two-stage torque. Set low in star. Set spec in star. Re-check on the ground.

Measure runout. Write it down. If you don’t measure, you’re guessing.

Plug-patch repair for punctures in the repairable zone only. No strings. No prayers.

Document everything. Photos, specs, initials, time. The road will ask you what you did. Be ready to answer.

He watched the way hands held those sheets. The clean-hands estimate writer held his like a passport. The father-and-son tucked theirs into their shirt pockets like flat stones they meant to skip across a lake.

Halfway through the afternoon, a young tech from a shop in Williams raised his hand. “What do you do,” he asked, voice tight with the kind of anger that is mostly fear, “when somebody stands in your bay with a phone and tries to make you into a punchline?”

Renee answered first. “You set a boundary,” she said. “Politely if you can. Firmly if you must. You explain that safety and attention require focus and that you’ll narrate when the work allows. If they insist, you stop. It’s your shop. You define the conditions of your labor. And—this matters—you keep your logs. Because when it turns into a complaint, logs are the language the people who decide things actually read.”

Then Eli added the part Renee wouldn’t. “You remember what they’re there for. Attention. You starve it. Make the work more interesting than the performance. It takes practice. So does everything that matters.” He held up the keychain. “You carry your broken. So when they try to break you in public, you know you don’t actually come apart.”

After class, the kid from Williams lingered. “You think you could look at my torque wrench?” he asked. “I think it clicks late.”

Eli tested it against Renee’s calibration block. “It’s honest,” he said. The kid’s shoulders dropped with relief. “But keep it calibrated annually,” Eli added. “I put stickers on the ratchets to remind me. Tools that lie are worse than people who do.”

The kid laughed. “People lie more often,” he said.

“Tools do more damage when they do,” Eli said.

The Ridge Riders tried one more theater before the curtain fell. They rolled into the city council meeting on a Tuesday night when the agenda looked sleepy and the cameras were low-fi. Public comment was a catchall basket for grievances that had nowhere else to sit. The lead Rider approached the microphone in a clean shirt that didn’t fit his mouth.

“Name’s Mason Furlong,” he said. “Flagstaff. I want to talk about public safety and city contracts.” He painted a story, careful as a man painting a barn, broad strokes to hide the grain. “You gave tax money to an old guy who’s a danger to the road,” he said. “He left a wheel loose on my cousin. We almost got killed. I got video of him fumbling around with a wrench. He’s senile.” The word hung in the room like bad perfume.

Nora was there because she went to meetings the way some people go to shows: for the human theater. She stood because the chair felt like it couldn’t hold her. The Fire Chief looked at the Mayor. The Mayor looked at the City Attorney. The City Attorney, who had never visited Eli’s shop but had watched the procurement logs travel from inbox to inbox, stepped up to the elbow of the dais and murmured something that made the Mayor’s chin lift.

“Mr. Furlong,” the Mayor said, voice even. “For the record: the city awards contracts based on objective criteria—capability, price, responsiveness. We also consult subject-matter experts where safety is concerned. In this case, the state DOT provided such expertise. Furthermore, the vendor in question documents all torque procedures with photographs and logs, which are public record. We won’t adjudicate your YouTube channel here tonight. If you have a specific, verifiable complaint, file it with Procurement. Otherwise, this forum is not for defamation.”

Mason scowled. “Defamation is when you lie,” he said.

“Exactly,” the Mayor said. “Next speaker.”

A woman in a Station 3 T-shirt stood. “Yes,” she said. “I’m Captain Ames. My signature is on those logs. We drove a child to FMC because a man knew a star pattern from a circle. That’s all.” She sat down. The room rearranged its posture around her.

When the meeting broke, Mason lingered in the foyer with his phone in his palm like a stone he couldn’t decide whether to throw. The other Riders were restless. This wasn’t the audience they knew how to feed.

Renee appeared from the side hall. She had attended in a jacket that made her look less like a cop and more like a neighbor you would trust with your spare key. “Mr. Furlong,” she said. “You ever consider putting your hands on a torque wrench instead of a camera?”

He blinked, then bristled, then let the air out of himself like a tire you decide to deflate before it bursts. “Maybe,” he said. “If someone shows me and doesn’t talk down.”

“I know a workshop,” she said. “It’s no-cost.”

He looked past her at Nora, who was watching with the kind of careful that means you have hope on a leash, ready to pull it back if it runs. Mason nodded once. “Okay,” he said. “Maybe I’m tired of being the joke-maker who turned into the joke.”

Renee didn’t smile. “Saturday,” she said. “Nine a.m.”

Winter arrived like a courthouse clerk: early, officious, unbothered by your plans. The Peaks wore white every morning, and the roads got the kind of shine that makes you feel like you’re driving on memory. The night before the storm that would be named later in the news, Eli sat at the kitchen table with the binder of torque photos open and the keychain near his elbow. Nora washed dishes and let them clink the way you do when you need to hear a thing that isn’t your thoughts.

“You ever wish I’d sold out?” Eli asked, half a smile to make it sound like a joke.

“Sold out to who?” Nora asked. “The chain shop that puts perfume on their air hose? The internet? Dad, you don’t sell out. You stock in.”

He looked at the keychain. “The year I made that, I was so mad at myself I couldn’t speak for a week.”

“You spoke,” she said. “You made a promise that fits in your pocket. You rub it like a worry stone and then you go out and torque twenty lugs like prayers. People can smell that kind of religion.”

He laughed, which unknotted something knotted. “Tomorrow we fill sandbags,” he said.

She smiled. “Tomorrow we fill sandbags.”

The storm came sideways. Wind. Snow flakes as sharp as salt. Visibility like the world had turned to breath. Calls stacked up on the county radio: slid-offs, abandoned vehicles, a plow with a tire delaminating under load on Route 180. The Fire Chief called Eli because the rig at Station 2 had an odd thrum that wasn’t quite a vibration, not quite a sound—like a violin string caught on a knuckle.

“I can come,” he said. “Roads may make me late.”

“We’ll get you a lift,” she said. Ten minutes later a city pickup nosed into his lot like a dog coming in out of weather. A firefighter slid over to the middle and patted the seat. “We’re running hot to cold things,” he said, and they went.

At Station 2, the engine bay was a bright box against the night. Eli stepped into the light, wiped his glasses, looked at the rig. He didn’t have the luxury of time for perfect procedures, so he used the thing he’d earned that very few people can name: judgment. He jacked, blocked, spun, read the tire with his palm, the way a baker reads dough. He set the dial indicator anyway because the needle is a truth-teller when your hand wants to be right. Six thousandths lateral. Enough to make the thrum at speed. He scraped the hub face, reseated, torqued with Renee’s voice in his head: torque is a promise. He did the pattern twice, then re-checked on the ground because the ground changes everything.

The Fire Chief appeared at his elbow like someone the storm had forgotten to erase. “You want a ride up to the plow on 180 after this?” she asked. “That delam’s going to strand a lane if we don’t make it stick until they can swap the set.”

“I’ll go,” he said. “Bring your brass brush.”

They reached the plow by following the way headlights thin out into a kind of resolve. The driver sat in the cab with the grim patience of men who push edges back from towns. The tire looked like a book coming apart at the spine. Eli knelt in the slop and did a thing he would never teach on a Saturday because it was one of those solutions that lives in the gap between rules and outcomes: he installed a plug-patch along a scar that wasn’t quite a puncture but wasn’t quite not either, seated the bead, aired to spec, torqued the rears in the snow with hands that had stopped being cold because the body had decided the work mattered more than comfort. He explained later, dry and careful, how the repair had been within the limits for temporary service and had been signed off by the operator; the city attorney would nod because temporary is a legal word and not just a hope.

The plow rolled. The road stayed open. Somewhere back down the grade, a line of ambulances at FMC didn’t get longer because the city could still exhale.

On the way back, the pickup fishtailed playfully and then obeyed. The firefighter driving glanced over. “How you still out here doing this at your age?”

Eli looked out the windshield like it was a story he could read. “Same way you are,” he said. “Somebody has to decide it’s their job.”

Spring came like it always does in the high country: first as rumor, then as puddles. Eli’s workshop list kept growing. Word had reached Winslow and Holbrook and places between. Mason started showing up early to help set out chairs and stayed late to coil air hoses. He was an awkward helper, earnest the way men are when they have not been given much practice. One Saturday, he brought a bag of cheap key rings and set them on the counter next to the epoxy resin.

“What are those for?” Eli asked.

“To make… more of that,” Mason said, nodding toward the broken stud in amber. “Not that exact thing. Our things. You said make your own.” He opened his palm. In it lay a small, bent cotter pin he’d picked up from the shoulder of Lake Mary Road on the day his throttle cable had hung and he hadn’t panicked for the first time in his life. “This is mine,” he said, voice almost embarrassed. “Figured we could start a bowl. Folks put in what they carry.”

Eli looked at the bag of rings, then at the cotter pin. “Put the bowl by the coffee,” he said. “Write a sign: BROKEN → TAUGHT.”

Later, when the room was empty, he cast a new paperweight. Not for the Chief this time. For the city attorney, who had told a mayor the difference between complaint and defamation and had made the air a little cleaner for the work to live in. He wrote a note in his slow block letters: For the desk that keeps promises in order.

Nora walked in when he was sealing the mold. “You’re going to resin the whole town if we let you,” she said, laughing.

“Good,” he said. “We’ll make it heavier than it is.”

They didn’t throw a ceremony when the city renewed his contract in the fall. Eli wouldn’t have gone. But the Chief shook his hand at Station 1 in a way that lasted the right length and Renee slid a calibration sticker onto his wrench with a flourish like a magician revealing the last card. Mason gave him a look that wasn’t quite an apology and wasn’t quite a salute, which is to say it was exactly what it needed to be.

“You’re stuck with us,” Nora said, locking the shop that night with the familiarity of someone who knew where the key lived by feel in the dark.

“Till my hands lie to me,” Eli said. “Then I’ll teach and stop touching other people’s wheels.”

“You’ll know before your hands do,” she said.

He thought of the sign by the register, the logs, the photographs, the Saturday classes where a kid from Tuba City had taught him a trick with a dial indicator he hadn’t learned in sixty-one years because the world still had surprises if you breathed right.

Later, at home, he sat at the table and turned the keychain over in his palm. He thought about mailing the original to the woman from Ohio whose wheel he’d saved two decades ago, to tell her that her panic on a summer afternoon had been turned into a thing that kept other people safer in a town she’d never think about again. He didn’t. Some promises are local. Some are private. This one had become both.

He drove at dusk out along Route 66 to where the asphalt opens its throat and the mountains lean back like they’re listening. He pulled onto the shoulder where the snowmelt had washed the gravel clean and stepped out. The air tasted like rain and old stories. Down the road, a pair of ambulances ran south with lights low—not urgent, not bored, a pace that said somebody would get where they were going in time to be told the good news: you’re going to be okay.

Eli looked down at the shoulder. Two faint arcs of rubber curved like handwriting across fresh sealcoat where a driver had braked perfectly to let a mule deer decide its future and then rolled on as if such small ceremonies happen every day—because they do, when people keep their promises.

He took the keychain from his pocket, pressed it into the soft palm of his hand, felt the cool shift to warm. He thought about torque values and runout and weights stuck to a rim, but more than that he thought about the way a wrench clicks at the exact moment your hand wants to keep going. The click is the tool saying, Enough. The lesson is learning to listen.

He listened. Wind in the pines. A truck’s distant downshift. The almost-sound of tires riding true. He looked at the red lights as they shrank, then softened, then became the idea of red—memory more than color—moving away along a road that was a little kinder tonight because a dozen hands in a dozen bays had made it so.

When he got back in his truck, Nora texted: You home for dinner?

He typed with a thumb that had earned its calluses two times over: On my way. Roads are good.

At the next light, a motorcycle idled beside him. Mason. He lifted a gloved hand in a small salute without theater. Eli returned it. The light went green. They rolled. For a second, their wheels turned in sync, then the bike surged ahead, not to show off, but because it was built to go and the road had given permission. Eli smiled and let him be what he was becoming.

Back at the shop later that week, the coffee can by the register had filled with the small, shiny confessions of a town that had decided to learn. Cotter pins. Split washers. A snapped-off valve core. A twist of wire. Mason’s ring of bent metal sat at the bottom like an anchor. Above the can, a new sign in Nora’s neat hand read: LEAVE SOMETHING YOU LEARNED THE HARD WAY.

People did.

One afternoon, a high school kid came in with his mom’s minivan and a dollar store set of plastic tools he’d bought with pride. Eli swapped the struts, balanced the wheels, torqued the pattern while the kid watched with reverence. On the way out, the boy dropped a small hex key into the coffee can and looked at Eli with a shy ferocity. “It rounded off the bolt,” he said. “I thought being careful was the same as being right.”

Eli nodded. “Careful is good,” he said. “Correct is better. You learn both.”

When the bay doors rolled down that night, the last light pooled on the concrete in a way that felt like a benediction. Eli shut off the radio, set the torque wrenches on their pegs, and took one long look at the wall where the broken stud hung in resin. He touched it like you touch a gravestone—not to summon ghosts, but to say, I carried you and I’m still here.

Flagstaff hummed. The mountains made their quiet shapes. Out on the highway, a pair of clean rubber arcs marked a place where everybody had stopped just right and then gone on. If you squinted, the arcs looked like parentheses, holding within them a small sentence the day had written: kept.

He locked up, stepped into the cold with his collar up, and breathed a breath that tasted like pine and solvent and the kind of hope that isn’t a wish but a habit. The keychain in his pocket thumped his leg as he walked. It was small. It was ridiculous. It was perfect.

He went home. And tomorrow, he’d open the door again and promise the road the only promise that ever mattered to him: the pattern, the torque, the truth—kept.