Emma Collins had never imagined that marriage could turn into a nightmare. When she agreed to marry Michael Thompson, she thought she was stepping into a loving family with deep traditions. Michael came from an affluent background, but Emma wasn’t poor either—she was raised in a respected middle-class home in Chicago, with parents who valued hard work and humility. She never flaunted the fact that her two older brothers, Daniel and Richard, had become wildly successful entrepreneurs. To the Thompsons, she presented herself simply as “Emma,” a community health worker who believed in small, steady good.

On the night everything cracked open, Los Angeles shone like a patient, expensive lie. The Glenmar Country Club floated over Bel Air like a lantern of glass. Strings of Edison bulbs were draped along white lattice; the valet line glittered with hybrids and hand-waxed classics. Inside the ballroom, a quartet bowed out Sinatra while servers in white jackets slid between linen-draped tables balancing silver fish forks and opinions. The Thompsons were in their element, glossy and admired, the sort of family that introduced themselves by listing memberships.

Emma fit herself into that world the way a leaf tries to become a bookmark—flat, careful, temporary. She had chosen a pale blue gown that made her eyes look like Lake Michigan in October. She’d tucked her hair behind her ears the way Michael liked it and told herself this was just another one of Patricia’s productions, the annual anniversary gala as a public service announcement: We are the Thompsons. Please clap.

At their table, Michael was on his second scotch and third story about a golf weekend with partners whose names sounded like corporate law firms. He touched Emma’s wrist when he wanted her to laugh; he looked away when she did. Patricia presided at the head, hair like spun platinum, posture like a sermon. Chloe scrolled, filmed, critiqued.

“What do you do again?” a man in a navy tux asked Emma, after confirming she wasn’t the waiter bringing the truffled canapés.

“I’m a community health worker,” Emma said. “South Side clinics. Maternal care, diabetes prevention, that sort of work.”

“How admirable,” he said, lengthening the syllables until they broke. “And you’re here with Michael.”

“I’m his wife.”

“Of course.” He smiled at Michael as if she were a funny premise.

She had learned to let these moments fall through her fingers like sand. But under the table she pressed her knees together and counted to five, a trick from childhood when thunderstorms and report cards had the same barometric pressure.

After the main course, when the band took a break and three dozen phones were deployed to capture the cake cutting, Patricia stood and tapped the stem of her champagne flute. The sound rang high and clear over the room like a bell in a tiled chapel. People turned. It was time for a moment.

“Friends,” Patricia said, casting her voice to corners where servers were resetting water glasses. “Thirty-five years. Thirty-five years of partnership, philanthropy, and family. We’re grateful to celebrate with you.”

There was warm applause. Patricia let it ride like a wave. Then she angled toward Emma the way a queen turns toward a peasant with interesting dirt.

“And tonight,” Patricia went on, “we also welcome our newest family member, Emma, the wife of our Michael. She’s shy,” Patricia laughed, not asking, “and we Thompsons want to make sure she feels… comfortable among us.”

Emma’s skin prickled. The men at the table angled their chins the smallest fraction, like the second hand on a Cartier ticking toward something.

“So, as a bit of harmless fun,” Patricia said, letting the pause ripen until it was not harmless at all, “Emma has graciously agreed to a little… confidence exercise. Isn’t that right, Chloe?”

Chloe brightened as if a light ring had just turned on. “Totally,” she said, standing, filming, smiling. “We did this at Kappa last year. You stand in the center and, like, own your body and your outfit and prove you’re not afraid of the gaze.” She pronounced it like a skincare brand.

Emma didn’t move. She tasted cold metal.

“Since Emma wants to prove she belongs,” Patricia said, the smile tilting, “let’s see how confident she is. Why don’t you show everyone what you’re hiding under that cheap dress?”

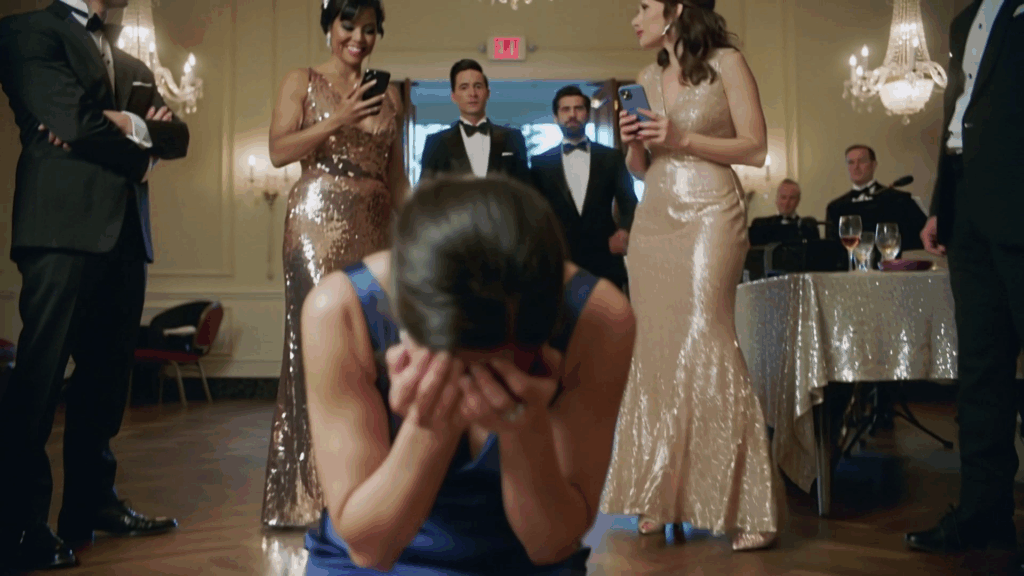

The word cheap landed like a coin tossed and not returned. The quartet stopped tuning. The room inhaled. Someone at the next table chuckled. Two of Chloe’s cousins—women who wore their insecurity like bracelets—rose and drifted toward Emma as if carried on perfume. Their hands came soft and quick, tugging at sleeves.

“Strip if you’re not ashamed,” one whispered loudly. “Let’s see if you deserve Michael.”

Michael lifted his glass and looked away.

Emma’s chair shrieked backward as she stood. Her body lit with panic, a flare seared into muscle memory. She had counseled assault survivors who trembled like this, who went quiet exactly like this. In her throat, a voice clawed upward and found the old trap door of silence.

No one came. Not the husband whose vows still warmed her left hand. Not the mother-in-law who called dignity a brand attribute. Not the sister-in-law who turned cruelty into content. The room was a satellite image: bright, far, false.

Somewhere, in the corner by the bar, a man lowered his phone. Another woman said, “Patricia, really?” in a voice that sounded like it was choosing seating charts for the rest of the year. But no one crossed the small, long distance between decency and action. Emma’s hands shook. She felt the slick drag of fingers at her sleeve and the rough edge of laughter.

“Please stop,” she said. It came out smaller than she meant.

And then the hall heard footfalls, heavy and unafraid, echoing off marble and money. The doors at the far end opened as if the room were an elevator and this was their floor. Two men in tailored suits crossed the threshold, and the air shifted the way it does before a Midwest storm when the sky chooses its side.

Daniel Collins had the lean patience of a man who had once cleaned virus-laced code off a server at three a.m. while bargain rent and appetite sat heavy on his chest. Richard Collins carried himself like a man who could read the bones of a building with his fingertips and had forgiven almost everyone who told him he couldn’t. People said the Collins brothers were handsome, but really they were certain. Certainty reads as beauty in America because we all want to be near the thing that doesn’t flinch.

“Emma,” Richard said, seeing her first, not the spectacle. His voice cut through the ice fog. He reached her as if no one else were in the room and folded her into a hug that said three summers on a cul‑de‑sac, two brothers teaching a kid sister to ride a bike, one Chicago winter of catching a snowball wrong and laughing anyway. “What’s going on?”

Patricia smoothed her expression with a hand that had never learned work. “This is a private family matter,” she said to the room, which was now the wrong audience.

Daniel’s laugh was a clean break. “Private?” He turned, gaze sweeping, eyes finding phones. “You invited two hundred people and a livestream.” He faced Michael. “You stood while your wife was assaulted.” The word landed properly. “And you had a drink.”

Michael’s mouth moved like he was trying to reel in something already in the water. “Daniel, this is being blown out of proportion. It was—Mom was only—”

“A joke,” Daniel said. “I heard that one in eighth grade from a boy who liked pushing girls down stairs.” The room flinched. He stepped forward, not angry like a torch but like a verdict. “Who thought humiliating a woman—your own daughter-in-law—was entertainment?”

No one answered. Phones tilted down like flowers after hail.

Chloe lifted her chin. “She’s not good enough for us,” she said. “She doesn’t belong in our family. We were just proving a point.”

Richard looked at her as if she were an interesting insect. “The point being that you are petty and bored?” His voice was mild, the way Lake Shore looks on a windless day until a freighter reminds you of depth. “Emma belongs anywhere she decides to stand. Not because of us. Because she has dignity. Try it sometime.”

Patricia said something about disrespect, but it didn’t arrive. The servers in white jackets had stopped moving. The band watched with their bows lowered. A woman near the doors put her hand over her mouth; a man in a tux examined the floor as if it had become a mirror.

“Get your hands off my sister,” Daniel said, no louder now than the sound of ice slipping in a glass, which is how you know a storm has settled in. The cousins who had touched Emma let go without thinking; their faces did the math of reputation and revenue and moved to stand behind a palm.

Michael tried one more small cowardice. “Emma,” he said with a smile meant for cocktail photos, “let’s talk about this in private.”

“In private is where you let them do it,” Daniel said. “We’ll talk here.” He turned to the room. “Here’s the talk: the age of smiling cruelty at charity tables is over. If you’re recording, record this.” He took Emma’s hand, held it up as if to show proof of life. “No one humiliates our sister.” He looked at Patricia. “Ever.”

The room exhaled a sound that was not applause. It was the small murmur a church makes after a confession lands heavier than anticipated. People stood, scraping chairs, rearranging consciences. The party ended the way expensive nights sometimes do, with men looking for checks and women looking for exits. The Thompsons tried to gather the shreds of their dignity like chiffon, but chiffon tears.

Outside, the air felt cleaner. A line of sycamores along the drive lifted their pale arms to a sky that had decided to be honest; even Los Angeles runs out of mirrors eventually. Daniel’s driver brought the car forward, a black sedan with more steel than flash. Emma slid into the back seat like someone coming in from cold.

“You should’ve told us,” Daniel said gently when the door shut, the world quieting like a coat pulled up.

“I didn’t want to bother you,” Emma said, and cried then in a plain way, no performance, the kind you can only do in front of people who remember your first library card. “You both have your companies and your lives. I thought I could handle it.”

“Emma,” Richard said, leaning in, his big hand finding her shoulder. “Family is the only thing you’re allowed to interrupt.”

What followed happened the way Midwestern crises do: methodically, with lists. Daniel’s general counsel drafted letters so clear they could be used as glass. Richard called a security firm he used on sites when local politics got loud. Emma, after sleeping sixteen hours, called a therapist whose office smelled like peppermint tea and notebooks. They met at Daniel’s place in West Hollywood, a house that didn’t brag, whose windows let in runnels of afternoon. When Emma walked out to the deck on the second morning and stood there watching jacaranda blossoms confetti the lawn, Daniel joined her and said, “We’re going to do this calmly. Calm wins.”

Calm looked like timelines and affidavits and a list of every hand that had touched her. Calm looked like a quiet PR plan that wasn’t about revenge but about dignity. Calm looked like the Collins Foundation doubling its grant to a South Side clinic and announcing a new program for assault survivors that would, coincidentally, be chaired by a woman named Emma Collins, who was qualified long before she was humiliated.

The Thompsons did not do calm. They did panic, then indignation, then strategy, which looked like asking their lawyer to draft a statement that said “misunderstanding” three times and “family” twice, with a picture of Patricia and Michael looking into middle distance like minor royalty. The statement did not land. The donors who read it had daughters.

Michael called. He texted. He emailed. The subject lines moved from “We need to talk” to “Please pick up” to “I made a mistake” to “You’re making this worse.” Emma let most of it land in a folder called Evidence. When she finally answered, she did it in daylight in front of Daniel and Richard and a woman named Adrienne who had been the coolest head in three mergers and a funeral. They put the phone on speaker.

“Emma,” Michael said, the word bending. “Babe—”

“Michael,” Emma said, and discovered she could pronounce his name without a single extra letter. “I’m filing for divorce.”

There was breathing. A swallow. The three-second pause of a man who has always believed pauses were a resource set aside for him. “Can we please discuss—”

“We’ve discussed. For a year. About your mother’s comments, your sister’s little games. About the time Chloe locked me out on the balcony ‘as a joke.’ About you telling me I was ‘too sensitive’ and needed to ‘relax’ if I wanted to fit. Do you remember what you said the day your mom suggested a separate table for me at Thanksgiving?”

“That was—”

“You said, ‘Don’t make a scene.’” She let the silence be an accurate measure. “I’m not making a scene, Michael. I’m making a decision.”

“Is this about money?” he said then, the old training surfacing. “Because you should know I’m willing to—”

“It’s about oxygen,” Emma said. “And I’ve decided to breathe.”

Adrienne tapped a note, the way a good attorney does when a client says something that both says everything and reveals nothing actionable. Richard leaned back and stared at the ceiling like it was an outfield sky and he was waiting for a catch. Daniel watched Emma’s face and let pride arrange his features without permission.

The paperwork moved fast. The prenup—insisted upon by Patricia, negotiated by a twenty-six‑year‑old Emma who thought love was a shelter that could withstand any weather—was fair as written and brutal as lived. Emma asked for what she needed and nothing more: the car in her name, the accounts she had funded herself, and a contribution to a community program as a term of settlement, because sometimes justice has to be taught in cash. She asked for an acknowledgment in writing: that what had happened at Glenmar was assault. Michael’s lawyer refused. Then he didn’t. The Thompsons could count; so could the court of opinion.

In Chicago, the city Emma loved like a flawed relative, summer settled in with the smell of cut grass and hot roofs. Emma rented a two-bedroom near Lincoln Park with windows that clicked open easily and a kitchen that understood soup. She went back to the clinic as if she had been away at a conference, not a war, and let her days fill with concrete work: appointments, check-ins, tote bags of prenatal vitamins, tough conversations about insulin and salt. She moved money quietly from her settlement into a fund for patient transportation because the number-one reason people missed appointments was buses.

On a Thursday in August, Emma stood in a fluorescent-lit hallway coaching a pregnant teenager to breathe through her first contraction when her phone buzzed. She ignored it. Later, over a paper cup of coffee, she saw a text from Daniel with a link and the three-dot preview: No one humiliates our sister. Ever. She clicked. The clip was from a press conference outside a glass building in San Francisco, where Daniel’s company had a lobby large enough to house a wedding. He stood at a simple podium with the company logo taped over—he didn’t use his firm for this—and read a statement. It was unembellished, which is rare in California. He named nothing specific, offered no adjectives larger than necessary. He said, “No one humiliates our sister. Ever.” Then he walked away. The video ended with the sound of cameras learning how to be quiet.

Emma watched it once. Then she put the phone down and, for the first time in months, laughed. Not the girls’‑night‑out kind, not the relieved kind, not even the triumphant kind. It was the laugh of a person who recognizes her life from the inside again.

The Thompsons did not laugh. Sponsors withdrew from their fall gala, citing calendars and principles. The country club’s board, which had “standards,” discovered theirs. Patricia posted a picture of a sunrise with a caption about kindness, then spent a week calling people who used to return those calls.

Michael found work less companionable. Men who had smiled at him in golf carts now preferred to talk on the back nine. Potential partners had daughters in college. The world would forgive almost anything if it remained off-camera, but Glenmar had been lit like a film set and America loves the replay.

In October, a judge stamped documents and Emma walked out of a courthouse with a last name she had never surrendered and a future that felt like an open window. She celebrated by buying new sheets and sleeping until noon and waking to light on the wall like a fresh habit. Richard flew in and dragged her to a Cubs game where they ate hot dogs like absolution and cheered for hope as if it were a team.

When winter came to Chicago—real winter, with wind that could refinish your bones—Emma found a rhythm. She saw a therapist who asked good questions and didn’t treat the Collins name like a skylight. She joined a Saturday morning book club at a coffee shop on Armitage where the owner remembered her order and her opinions. She ran by the lake in a coat that made her look like an astronaut and learned the exact moment the water turns from steel to mercy. Once, she stood on North Avenue Beach at dusk and watched the skyline perforate a pink sky and thought, astonishingly, that she was happy.

In February, the clinic’s director announced he was moving to Denver to follow a person Emma had met once and liked immediately. “You should apply,” he told Emma in the same tone he used to tell patients they were brave. “You won’t be the smoothest choice. You’ll be the right one.”

Emma applied. She wrote about proof, not promise. She wrote about the body as a political jurisdiction and South Side buses in January snowfall and the right to not be afraid on balconies. She met with a board that had worked in rooms like Glenmar and rooms with folding chairs and listened to her like both were important. They offered her the job in a voicemail that made her cry on a Thursday morning over toast.

She said yes. She said yes again to a donor dinner where she and Daniel and Richard sat at a table where the conversation didn’t have to be convinced of her worth. She said yes to a late-night email from a resident physician at Northwestern who wanted to start a teen mothers support group and had never had a budget line that didn’t make her flinch. She said yes to herself by buying a plant she would try not to kill.

The night of the clinic’s spring fundraiser felt, at first, like temptation—a room again, a dress again, a microphone again. But the ballroom at the Drake Hotel belonged to a Chicago that had raised her, not a Los Angeles that had tried to rebaptize her in shame. The chandeliers didn’t sneer. The band played Curtis Mayfield and Sam Cooke. The donors wore suits that wanted to help.

Emma stepped up to a modest acrylic podium and told a story about a woman who had taught her to make soup and to call in sick to rest, too. She mentioned buses and prenatal vitamins and February sidewalks and the miracle of a blood pressure cuff. She did not mention the Thompsons. She did not mention money beyond its ability to turn into care. When she finished, the applause was long and not performative. She saw Daniel in the back, hands jammed in pockets because he didn’t know what to do with them when he wasn’t holding an answer. She saw Richard wiping at his eye in a way that suggested dust.

After, at the bar, a man with salt in his beard and kindness in his shoulders introduced himself as Dr. Theo Hart, pediatric ER, University of Chicago. He said he liked her speech and the way she didn’t ask for pity. He told her a story about a five-year-old who had come in at midnight in a Halloween costume in March. He asked if he could bring his residents to visit the clinic on a Saturday. She said yes to that, too.

They did not fall in love on the spot. They exchanged emails like decent people. He came by with four residents and six questions and the sort of listening that should be pharmacological. He stood in the doorway of Exam Room 3 and watched Emma talk to a grandmother about food deserts and you could see him recalibrate his understanding of heroism.

When spring finally took off its coat, Emma and Theo walked by the lake and argued about the best diner in the city. He said Lou Mitchell’s; she said White Palace. She won. In June, he cooked for her in a kitchen so tidy it looked like an apology for every ER shift that had come before. The relationship grew the way good ones do, as an agreement between two people to tell the truth and not leave when it’s inconvenient. Emma told him the whole Glenmar story on a Sunday afternoon as light shifted across her living room like a timetable. He listened as if listening were an act, not a waiting room. When she finished, he said, “I’m sorry that happened to you,” and then, “It won’t happen again,” in a voice that did not sound like a threat so much as a promise to always choose the right side of the room.

Summer returned. News cycles moved on to elections and celebrity marriages and a fighter who wouldn’t retire. The Thompsons resurfaced the way mold does: apologetically and with a PR firm. Patricia gave an interview on a podcast where she used the phrase “cancel culture” and a laugh that sounded like jewelry. Chloe announced a brand partnership with a mindfulness app and filmed herself crying in a parked car. Michael sent Emma a message on her birthday that read, simply, I hope you’re well.

She was. She did not reply.

In August, a letter arrived at Emma’s office on thick paper that wanted to be respected. It was from a law firm in Beverly Hills representing the Thompsons. The letter said that clips from the Glenmar incident had been “doctored” and that certain “malicious narratives” were harming the family’s reputation and that if the Collins family did not retract certain statements, the Thompsons would be forced to consider legal avenues, which is to say, noise.

Emma read it once, twice, five times. Then she sent it to Adrienne. Adrienne called and laughed for a whole excellent minute. “Defamation requires a false statement of fact,” she said when she had oxygen again. “Also, bless their hearts.” She drafted a response that was both a lullaby and a threat and cc’d three people whose cc was a language.

Two weeks later, a different letter arrived—this one not on thick paper but on a plain email, and it came from a man who had stood at the back of the Glenmar ballroom that night with his hands in his pockets because he hadn’t known where else to put them. He wrote, I was there. I was a coward. I’m sorry. If you ever need a statement, let me know. Emma did not reply to that one, either, but she filed it where documents go that might one day tilt a scale.

Autumn brought the clinic’s pilot program for teenage mothers, the Saturday group with Theo’s residents, and a grant that would turn an empty storefront on 63rd into a nutrition classroom with a stove and a table and a chalkboard. Emma showed up on the first day and wrote on the board: What do you cook when you’re tired? Women laughed and said cereal and noodles and the one soup their aunt had taught them, and Emma felt the kind of glad that has muscle.

One evening in November, as the city turned its midwestern face toward winter again, Emma left the clinic late. She tugged her scarf higher and walked to the lot. The sky above was the color of a television that had given up. A black SUV rolled slowly past and stopped near the entrance, windows dark, engine patient. Emma’s heart thudded in the new way hearts do after they have once been introduced to fear with a name tag. The driver’s window slid down.

“Emma,” Michael said. He looked smaller. Money keeps people a certain size for a while, but shame is a tailor.

She stood a safe distance back. “You can’t come here.”

“I’m not here to start anything.” He glanced around as if looking for an audience who could help him remember who he was supposed to be. “I heard about your program. About the clinic. I wanted to say… you look happy.”

She waited. He had not learned economy.

“I’m sorry,” he said finally. The word hung between them like a paper lantern in rain. “For that night. For all the nights before it. I should have—” He stopped, because the list was long and time had become a thing he rented. “I’m in counseling,” he offered, like a business card.

“That’s good,” Emma said. It was, and she meant it. She meant also that forgiveness is a room you can paint and never move into. “You can send any further communication through Adrienne.”

He nodded. He looked past her at the clinic’s lit windows, where two silhouettes leaned toward one another the way people do when the conversation is finally honest. He looked like a man who had once been invited to a life and had RSVP’d Maybe until the party ended. “Take care,” he said, which was the first true thing he’d said in a year.

“Take care,” she said, and walked to her car and drove home without checking her mirror more than necessary.

December set in with a kind of cheerful vengeance. Theo gave her a scarf he’d found at a market on 18th Street—soft as an apology—and she gave him a book about a doctor who had decided that an exam room was a political act. Daniel flew in with a woman he’d been seeing who worked in urban planning and wore optimism like a habit. Richard arrived with his kids and a caramel cake that had not survived the flight intact. They all piled into Emma’s apartment and tried to find enough mugs.

On Christmas Eve morning, Emma and Theo delivered gift bags to the clinic—diapers and onesies and tiny socks and grocery cards tucked into envelopes with hand‑written notes—and then walked up Michigan Avenue under lights that made even the wind behave for a stretch. They ducked into a church at Wabash where a choir was rehearsing, stayed for “O Holy Night,” and considered, without saying it, the way traditions can be rebuilt.

In January, the clinic reopened after a snow day and the radiator hissed like an old cat and Emma felt her life gather itself and proceed. A journalist from a national magazine called to ask if she would speak on the record about Glenmar in a piece on “power and women and public shaming.” Emma asked if the piece would feature three women who had no famous brothers. The journalist said yes. Emma said yes, too, and hoped she could make a sentence that tasted like a door opening and not a headline.

When the story ran, it was good journalism, which is to say it complicated instead of simplified. Emma’s quotes were not heroic; they were true. She said, “The worst part wasn’t the joke; it was the room.” She said, “A bystander is a role; so is a rescuer.” She said, “Dignity is not something you lend.” The responses were kind, and some were disagreements from women who had chosen different paths and wanted to be seen, and Emma read those, too, and thought about how no one’s survival story should be a curriculum for anyone else.

Spring returned like an apology you accept without forgetting. The pilot program became a permanent program, and the nutrition classroom filled with frying pans that knew their purpose. Theo moved a toothbrush into Emma’s bathroom and then a jacket into her closet and then a laugh into her mornings. The Collins Foundation endowed a scholarship for community health workers who wanted to stay in their own neighborhoods. Richard bought a building near the clinic at a price that made the seller feel lucky and the neighborhood feel heard, then set the rent at a number that would have made his investors roll their eyes if he’d had any.

On a May evening, under a string of lights that reminded her briefly of Glenmar and then didn’t, Emma stood on a small stage at the opening of the new classroom and said a few words to people who had come not to be seen but to see. Halfway through, Patricia walked in.

It took the room a full five seconds to re-balance. The older woman paused at the back as if measuring the distance to a thing she had not earned. She wore gray, which was new for her; even her jewelry looked like it had been told to use its inside voice. Two men from the firm stood behind her with faces like unlined paper.

Emma did not stop speaking. She finished her story about a grandmother and a blood pressure cuff and a bus pass and then she said, “Thank you,” and stepped away. She stood at the back, near a table of cookies, and waited. Patricia approached as if walking upstream.

“I came to apologize,” Patricia said, and the room rotated to keep them in view without looking like it was doing so. “Formally.” She produced an envelope, heavy paper, embossed. “And to make a donation.” She nodded toward a second envelope. “Substantial.”

Emma looked at the envelopes but not the numbers inside them. She thought about nights and rooms and women and doors. “You don’t have to do this here,” she said. “You can mail it.”

“I wanted to do it in person,” Patricia said, and for the first time in her life, or at least the first time in this story, her voice sounded like a person’s. “What I did was unforgivable.”

“That’s not for me to adjudicate,” Emma said. “Forgiveness is none of my business when it comes to you. Accountability is.” She waited. Patricia waited, too, and that felt new. “As for the donation—if it’s unrestricted, we’ll accept it. If it comes with a plaque, we won’t.”

Patricia blinked. “No plaque,” she said. “No naming. Just… do something good with it. The way you do.” She hesitated. “Michael is in a program. He seems… smaller. I thought you might want to know.”

“I saw,” Emma said. Then, because it cost her nothing and might buy someone else a Tuesday morning, she added, “I hope it helps.”

Patricia nodded and left, moving like a woman who had carried something heavy for a long time and had finally put it down but would always remember its shape.

Daniel found Emma by the cookies. “You all right?”

“I am,” Emma said, and she was surprised by how true it was. She slipped the donation envelope to the clinic director. “Unrestricted,” she said, and the director’s eyes shone the way eyes of people who have learned to make much out of little do when given the chance to make much out of much.

Later, out on the sidewalk, Theo took Emma’s hand as if that were his contribution to the city’s infrastructure. Traffic moved on 63rd with its usual arguments. Somewhere a radio played Sam Cooke and somewhere else a kid kicked a ball at a garage door and disagreeing voices reached agreement because dinner was ready.

Emma thought, briefly, of the country club lights and the way a room can turn on you and the way another room can save you. She thought about her brothers walking into a ballroom as if walking into a promise they had made to a girl on a sidewalk in Chicago twenty years before. She thought about rooms she would build now—exam rooms and classrooms and rooms where women sat in circles and remembered how to speak.

Months later, at a small press conference in front of a brick building that used to sell auto parts and now would sell carrots and cooking skills, a reporter asked Emma what she would say to other women who found themselves in rooms like the one at Glenmar.

Emma considered the camera, which had learned some manners. “I’d say,” she began, and glanced at Daniel and Richard and Theo, who stood off to the side pretending not to listen because that’s what you do when a woman you love speaks for herself, “that you’re not auditioning. Not for a family. Not for a society. Not even for yourself. You already belong—to your own life. If you can leave the room, leave. If you can’t, call someone who will walk in.” She smiled then, not for the cameras but in case a woman somewhere needed a picture of what a future can look like. “And if you don’t have that person yet, go to a clinic on 63rd. We’ll help you find her.”

After the cameras were folded and the podium was carried inside and the last volunteer wrapped the last tray of cookies in plastic to take home to a neighbor, Emma stood on the sidewalk and watched the sky pull out its evening colors. The city hummed its river song; the El grumbled its lullaby. She hooked her arm through Daniel’s and Richard’s and then through Theo’s, and together they walked across the lot toward a door she had keys to.

No one would ever strip her of anything again. Not in a ballroom, not in a comment section, not in the small hours of a night that thought it had her name. And if the world tried, as it sometimes would, she had a way to answer that had nothing to do with fury and everything to do with rooms: she would build another one. And another. And another, until there were so many rooms where dignity lived that the old rooms had nothing left to do but take down their mirrors and hang a window instead.