Daniel Carter got off the I‑95 one exit early, a paper bag crinkling on the passenger seat and the smell of mint‑chip ice cream seeping up through its cardboard lid like a promise. The October light over West Haven was thin and gold, the kind that made maple leaves look like stained glass and made even his tired duplex on Alder Street seem briefly like something out of a postcard. He parked under the city‑issued sugar maple, glanced at the clock—4:18 p.m., earlier than usual—and pictured his eight‑year‑old flying down the hall at the sound of his keys, socks skidding, hair everywhere, that breathless, high laugh that had become rarer in the past year.

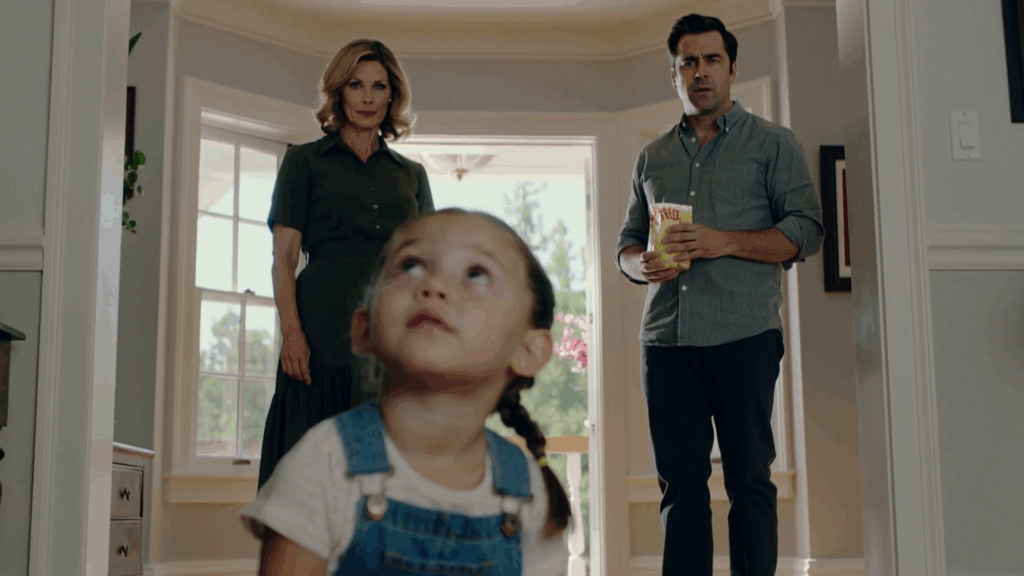

He let himself in quietly. The house smelled like lemon cleaner and something scorched. Melissa’s voice reached him first, clipped and sharp, a metronome of criticism beating time against tile. “Do it again. If you’d used your wrists like I showed you, it wouldn’t look like that. Don’t stop until it’s spotless.”

A second voice—a small, breathy “Yes, ma’am”—and then the scrape of a brush on floor. Daniel rounded the corner and his world narrowed to a single, terrible frame: Emily on her knees on the living room hardwood, an old nylon scrub brush gripped in both hands, a bucket of gray water beside her. Her ponytail was stuck damply to her neck. Her palms, raw at the heel, were bright with that thin, dangerous kind of blood that came when skin cracked and kept cracking. Melissa stood above her with her arms crossed and a white dish towel folded over one wrist like a second mouth.

The bag fell. The ice cream thudded and rolled and dented the baseboard. “Emily,” he said, or maybe he shouted it; the sound that tore out of him ricocheted through the room and came back a stranger. “Emily! What the hell is going on here?”

Melissa started, then smoothed her mouth into the prim concern she wore like lip gloss. “She wanted to help,” she said. “She insisted. I told her—”

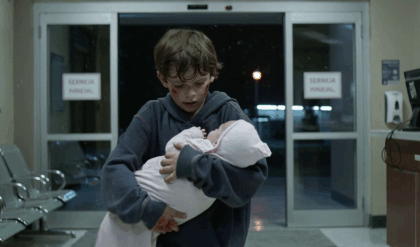

Daniel was already moving. He scooped his daughter up, the brush clattering across the floorboards. Her small body was all awkward elbows and weightless trust, hot as fever where her cheeks pressed his neck. “Daddy,” she whispered, the breath sticking in her chest, “I’m so tired.” The words landed like a diagnosis, like a sentence he’d been too cowardly to read.

“Bathroom,” he said, and every word to Melissa came out as a shard. “Get the first‑aid kit.”

She stepped back, color rising along her throat. “You’re overreacting. She’s dramatic, Daniel. She needs structure. Responsibility.”

“What she needs,” he said, adrenaline making his voice almost calm, “is a childhood.”

He carried Emily down the hall. The mirror over the sink caught them in a harsh rectangle of afternoon: his face gray with road‑fatigue and something older, a muscle moving in his jaw that he usually kept perfectly still; her face a small oval of resolve and apology that broke him open. He ran lukewarm water over her hands, watching pink thread into the stream and swirl away. When the cracks stung she held his eyes to steady herself, and he felt the terrible tug of all the times he’d missed it—arriving home after bedtime, accepting Melissa’s “she’s fine” with relief because it was easier to be the person who believed.

Later he would think of specific moments, like beads on a string: the school nurse’s voicemail he returned two days late, the way Emily’s laugh had flattened into something quieter, the fact that Melissa had moved the step stool out of the kitchen—“It’s a tripping hazard”—and how Emily had stopped baking box brownies with him on Sundays. He had let himself be managed. He had let himself be blind.

He dabbed ointment onto the fissures and lifted her gently to sit on the counter. “Sweetheart,” he said, keeping his voice low and normal because he could feel panic banging at the door, “tell me what’s been happening when I’m not here.”

Her eyes moved to the doorway. He closed it, turned the lock he’d never used, and crouched so they were eye‑level. “You can tell me. I promise I’ll protect you.” He had said those words the night her mother died under a sky of hospital fluorescents. He had promised and then let a woman with an immaculate Instagram kitchen teach his daughter to shrink.

Emily swallowed. “She makes me wake up when it’s still dark to start the laundry,” she whispered. “And I have to scrub the floor because I spilled orange juice once. If I don’t finish before lunch, I can’t eat.”

He put a hand on the counter to steady himself. “She kept you from eating?”

“Sometimes,” she said. “She says I’m being dramatic when I’m hungry. She says I’m…a burden.” The last word came out hushed, like a curse she was ashamed to know.

It took Daniel three slow breaths to trust his voice. “You are not a burden,” he said. “You are my daughter.”

Down the hall, Melissa’s footsteps hovered and moved away. He could feel the shape of the argument they were going to have; it was as big as a room. He wrapped Emily’s hands in gauze and kissed the crown of her head and carried her to her bed. He turned on the string of fairy lights her mother had once draped there, and for a second grief and fury braided together so tightly they were indistinguishable.

Then he went looking for Melissa.

They met at the foot of the stairs like actors on a particular line they had rehearsed without knowing. “How dare you,” he said softly, which was worse than if he’d shouted. “She’s eight.”

“Don’t do this, Daniel,” she said. “Don’t make me the villain because you can’t set rules. She is lazy. She needed structure. You’re raising a child who will be helpless.”

“My child is not helpless,” he said. “She’s hurt.” He gestured toward the living room, the damp circle of floor like a wound. “Look at what you made her do.”

“What I made her do?” Melissa laughed then—a brittle, thin sound. “You are unbelievable. You lap up her crocodile tears and leave me to do the hard work. You’re always the hero swooping in with ice cream while I’m the one keeping this house running.” She snapped the dish towel against her palm. “Go ahead, call the police. Call anyone. See how far your ‘she had to clean’ sob story gets you.”

It turned out “far” was a call to the pediatrician’s on‑call nurse, who told him to document the injuries and go to urgent care now; a mandated report to the Department of Children and Families; a uniformed officer named Sera Pugliese on their front step with a soft voice and a notebook; a list of instructions and a case number; the word “protective order” sitting there like a bridge he would have to step onto if Melissa did not leave.

She didn’t leave that night. She shut herself in the master and texted furiously. Daniel slept on the floor in Emily’s room with his hand near the edge of her bed like he could catch her if a bad dream tried to pull her under. The house breathed around them: the HVAC clicking to life, the refrigerator motor’s familiar hum, the quiet of a neighborhood that tucked in early because morning started early. He stared into the dark and thought about the day he met Melissa at the New Haven Food Truck Festival, her cherry‑red dress and the way she’d told him she loved kids, loved structure, loved the feeling of a home “running like a tuned piano.” He thought about the comfort of recipes and the way grief had made him susceptible to any woman who said the word “family” with confidence. He thought, over and over, of Emily whispering I’m so tired.

In the morning, he told Melissa to pack a bag. “Until we figure this out, you can’t be here,” he said. “There’s going to be an investigation.”

“You’re really doing this,” she said, blinking like he’d turned a spotlight on her. “After everything I’ve done for you. For her. You’re going to humiliate me.” Her eyes flashed a hard, flinty blue. “Fine. But don’t expect me to come back to a house where a spoiled brat runs the show.”

“Get out,” he said, because there were sentences you couldn’t come back from, and she had just said one.

She left with a suitcase, pausing in the doorway as if waiting for him to run after her. He didn’t. He stood with his hand on the small of Emily’s back and watched the door close.

The pediatrician at Yale New Haven’s urgent care introduced herself as Dr. Patel and examined Emily’s hands with a gentleness that made Daniel want to both cry and apologize to her and to every nurse who had ever had to hear a parent tell a story like his. “These are friction injuries,” Dr. Patel said evenly. “The pattern’s consistent with repetitive scrubbing without protection. We’ll clean them again and cover them. I’m making a note about food withholding. Do you feel safe at home now?” Her eyes flicked to Daniel.

Emily looked up at him, then nodded. “Yes.”

On the way out, Officer Pugliese called to say she’d filed her report and that a social worker named Tessa O’Neill would be in touch. “This is hard,” the officer said. “You did the right thing.”

In the parking garage, Daniel buckled Emily into her booster and leaned a hand on the roof of the car. He had the disorienting sense of being someone else, some other father who had failed at the one job he believed he could not fail. “Hey, kiddo,” he said, keeping his voice light. “You want pancakes for dinner?”

She nodded. “With blueberries.”

“Deal.”

At home he pushed open the kitchen window and let cool October air knock out the lemon cleaner. He set a stool by the counter like he should have insisted on months ago and showed her how to flick watery batter onto the skillet to test the heat. They ate on the back steps because it felt easier to breathe under sky. Emily picked a crispy edge off a pancake and told him that the art teacher at Lincoln Elementary let her stay after school sometimes to draw. “She’s nice,” Emily said. “Her name is Ms. Whitaker. She smells like cinnamon gum.”

Two days later, Tessa arrived with a canvas tote and a calm, practiced face. She sat at the kitchen table and asked questions that seemed simple and were not. How many hours did Melissa spend with Emily each day? Had anyone else observed discipline that concerned him? Had he noticed changes in Emily’s weight, sleep, performance? Had Melissa ever acknowledged striking her? Neglect? Cruelty couched in tasks?

“She said it was responsibility,” Daniel said. “She used that word a lot.” He told Tessa about the laundry in the pre‑dawn hours, the scrubbing, the missed lunches standing on the other side of a locked pantry door.

Tessa’s pen paused. “Locked pantry?”

“The latch,” Daniel said, heat rising in his face as if he were the one confessing. “She put a childproof latch on. For ‘snack control,’ she said.”

Tessa wrote. “We’ll be recommending a safety plan. I’m going to schedule a forensic interview for Emily at the child advocacy center so she only has to tell this once.” She looked up at him. “I know you want to fix it. For now, let us document. And keep things as normal as you can.”

Normal. He tried. He moved his workday where he could—he’d been a project manager at North Shore Building for eleven years and had banked goodwill he hadn’t realized he’d need. He got used to grocery runs with a small hand inside his elbow and the quiet discipline of making a house soft again: folding back the sharp corners of routines, opening doors that had become metaphors. He took the lock off the pantry and left the hardware in a jar like a warning to himself.

The child advocacy center sat in a renovated Victorian near the Green, its porch bright with mums. In the waiting room a fish tank bubbled and a teen volunteer sorted crayons by color like absolution. Through a one‑way mirror Daniel watched the interview room, where a mural of a Connecticut coastline bent into view and a woman with a braid introduced herself to Emily and asked her, with practiced patience, to tell the story in her own words. He stood with his shoulder against the cool glass and listened on a headset and swallowed hard at the parts he already knew and the parts he didn’t: the dish towel snapped near Emily’s face when she “moved too slow,” the way Melissa had told her that tears were “manipulation,” the afternoon she had made Emily kneel on rice for ten minutes “to learn.” He felt sick. He felt like someone had swapped his bones for wire.

Outside afterward, the sky was a high hard blue. They bought hot chocolate from the food cart near the library. “You did great,” he said. “I’m proud of you.”

“Will she be mad?” Emily asked.

He did not pretend not to know who she meant. “She doesn’t get to decide anything about you anymore.”

When Melissa’s attorney sent an email accusing Daniel of alienation and melodrama, Daniel took the printout to a lawyer of his own. Her name was Carla Nguyen, and her office on Orange Street was lined with books whose spines read like a foreign language he was suddenly going to have to learn. She listened without interrupting and then put the printout down like it was a prop in someone else’s play. “We’ll file for divorce,” she said, “and for emergency orders granting you temporary sole custody. We’ll ask for a protective order for Emily. We’ll urge DCF’s involvement to be formalized in our motion. And we’ll prepare you for how ugly this might get.” She leaned forward. “I need witnesses. Anyone who saw or heard something. Neighbors. Teachers. The school nurse. The babysitter.”

He thought of Mrs. Reed next door, the one who baked molasses cookies at Christmas and apologized when her golden retriever barked at nothing. When he knocked on her door, she opened with flour on her palms and listened with widening eyes. “I wondered,” she said softly. “I saw her out there with the trash bags last month—way too heavy. I filmed because I thought…in case. I should’ve showed you. I’m sorry, Daniel.” She sent him the video, the pixelated proof of a child staggering under a bag half her size while a woman in a white towel glanced out and closed the door.

Carla watched the clip twice and nodded. “This matters,” she said. “It corroborates pattern and supervision issues.” She made notes. “We’ll also ask the school to produce attendance and nurse logs. And we’ll bring Dr. Patel’s report.” She met his eyes. “You may feel like you’re on trial. You’re not. She is.”

At the first hearing in New Haven Family Court, fluorescent lights washed everyone the same color. Melissa wore a navy dress and a small cross and an expression calibrated to communicate wounded dignity. Her lawyer, a sleek man with silver hair, tried to make the case about discipline and culture and the dangers of permissive parenting.

“We don’t jail parents for requiring chores,” he said, placing his palms on the table like scales. “We don’t call the Department for household expectations. This is a man grieving his late wife who misreads structure as cruelty.”

Carla stood without rustling a page. “We all agree chores are part of family life,” she said. “We do not agree that withholding food, compelling a child to perform hours of repetitive manual labor causing documented injury, and locking access to nourishment constitutes ‘structure.’ We call it neglect and emotional abuse. We call it dangerous.” She let the word hang so even the court reporter had to look up. “And we have a child’s clear statement and a neighbor’s video and a doctor’s report to support it.”

Judge Alicia Monroe peered over her glasses. “Is the child present?”

“No, Your Honor,” Carla said. “Given her age and the availability of the recorded forensic interview, we’re requesting the court rely on that.”

The judge watched the video later in chambers; when she returned, she signed the temporary orders with a black pen that shone in the fluorescent light. “Temporary sole custody to Mr. Carter,” she said. “No contact with the minor child absent therapeutic supervision. A protective order for the child. We’ll set a date for a full hearing. Counsel, I trust you will advise your client about the risks of noncompliance.” Her gaze shifted to Melissa.

Melissa’s face tightened. For a second Daniel recognized something he had tried for months not to see: not sadness or misunderstanding, but entitlement. If she had been asked to choose between accepting a boundary and winning, she would choose winning every time.

The house on Alder Street learned new sounds. Saturday mornings became pancake mornings for real, not just emergency measures against fear. They discovered that their dining table looked like a place where a family lived if there were crayons in the middle of it, not centerpieces. They took in a rescue mutt from the shelter—brown with white socks and a perpetual expression of delighted surprise—and named him Rocket because he ran diagonals in the backyard like a firework. Daniel found a half‑finished birdhouse in the garage from before Melissa had “purged clutter” and asked Emily if she wanted to paint it. They watched goldfinches find it a week later and learned they could be happy just by noticing.

At school, Ms. Whitaker called to say Emily had won the fall art contest. “She drew a floor,” the teacher said, laughing softly at Daniel’s silence. “A floor with sunlight on it. And there’s a small brush in the corner that the sun doesn’t reach. It’s…hopeful, Mr. Carter. It’s very hopeful.”

Therapy twice a week felt like driving to a town whose streets he didn’t know yet. Dr. Lila Martinez specialized in trauma‑focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children. In her office there were shelves of tiny figurines for sand‑tray work and a lava lamp that glowed like a small planet. Daniel sat in the waiting room, read brochures he never wanted to need, and learned how to say things like “I believe you” and “It wasn’t your fault” out loud to a person who took notes and nodded. In conjoint sessions, he practiced making promises he could keep. He learned that repair was a verb.

Once, after a session where Dr. Martinez taught Emily how to feel big feelings without drowning, they stopped at Dunkin’ on Chapel. Emily got a chocolate frosted with sprinkles. Daniel took a bite of his plain cake donut and said, “I want you to know something. If you ever feel scared, about anything, and I don’t see it right away, you can say it out loud and I will hear you.”

“I know,” she said matter‑of‑factly like she was telling him his own birthday. “You hear me now.”

He nodded, blinking at the traffic light, the little walking person blinking to white. “I hear you now,” he said.

Melissa tried, once, to corner them in the parking lot of the grocery store, stepping out from behind a minivan with a smile sharp enough to cut her lips. “Daniel,” she said. “This is ridiculous. We can talk like adults.”

He felt Emily press into his side. He reached for his phone, but he didn’t need to. Officer Pugliese happened to be walking out with a coffee and a carton of eggs. “Ma’am,” she said, stepping between them. “There’s a protective order. You need to leave.”

Melissa’s mouth twitched. “Of course,” she said, sweet as antifreeze, and slid away. Daniel exhaled the breath he’d been holding since May.

The full hearing took place a month later. Carla called witnesses and kept her questions tight. Mrs. Reed testified softly, her hands folded around a tissue she never used. The school nurse spoke to weight loss too small to flag a chart but big enough to flag a heart. Dr. Patel explained friction injuries for the record in terms so plain even the bailiff nodded.

When it was Melissa’s turn, she cried in the correct places and talked about “generational values” and “teaching girls to be capable.” She said “my house” twice before catching herself and amending to “our house.” Her lawyer asked her whether she’d ever withheld food.

“Never,” she said immediately, and Daniel watched the judge write something down. He imagined the black line of the lie traveling to a place inside the record where it would cool into fact.

Carla said, “Is it your testimony that the child had daily access to the pantry?”

Melissa paused a fraction too long. “Of course,” she said. “Within our rules.”

“Which included?”

“Appropriate timing,” she said. “And asking permission.”

“And a latch,” Carla said.

“There are childproof latches on many pantries,” Melissa said. “It’s common.”

“On pantries where the children are toddlers,” Carla said mildly.

After closing arguments, Judge Monroe took a recess. In the hallway, Daniel stared at the mural of a Connecticut river cresting green glass and felt Emily’s small hand slip into his. “Do we have to talk again?” she asked.

“No,” he said. “We did the hard part.”

When the judge returned, she read her ruling into the fluorescent air in a cadence that seemed both impersonal and merciful. She granted Daniel full legal and physical custody. She ordered therapeutic, supervised contact only at the discretion of Emily’s therapist. She found that Melissa’s conduct had been “coercive and neglectful” and that her testimony had been “inconsistent with documentary evidence.” There were words about safety and best interest and then the gavel was just a wooden sound.

Outside, the air felt newly breathable. Carla shook his hand like a teammate at the end of a game nobody had wanted to play. “Take your daughter home,” she said. “Live your life.”

They did. Life did not turn into a montage—there were still mornings when Emily woke from a dream so fast she had to throw up, still days when Daniel looked up at the ceiling at 2 a.m. and worried that he had made his daughter’s world smaller by making it safe. But there were also trivia nights at the community center where Emily got all the bird questions right, and a Sunday afternoon when they baked brownies again and didn’t burn the edges, and a Tuesday when Rocket learned to sit and then immediately forgot again because joy made him stupid.

On the first snow, Daniel pulled the box of mittens from the hall closet and found, at the bottom, a postcard his late wife had once used as a bookmark. It showed a lighthouse on the Rhode Island coast, white and red against a sky the color of reflection. He taped it on the fridge. “Let’s go there in the spring,” he said to Emily. “Let’s make a place where winter can’t reach us.”

Spring came with its own greenness, almost indecent after so much gray. In April they drove down to Point Judith with paper cups of fries and a thermos of lemonade. They watched the water push itself toward the shore and fall back, tried to name the boats by the way they cut their wakes. Emily collected stones with changeling veins. “This one looks like marble cake,” she said, serious. “This one looks like a storm that forgot what it was doing.”

He wrote a letter at a picnic table while Emily arranged her stones. He wrote to the woman he had loved and to the version of himself he had been when she died. He wrote the sentence he had been afraid of: I failed for a while. Then he wrote the one he wanted his daughter to remember: I didn’t keep failing. When he folded the letter and put it in his pocket, the wind didn’t try to steal it. Some things you had to carry.

On a warm night in June, under a string of lights on their back porch, Emily fell asleep against his side while he read aloud the last chapter of Charlotte’s Web, the part where Charlotte makes something as ordinary as a word into a rescue. When he reached the end, he closed the book and sat with the weight of his daughter heavy and good against him, listening to Rocket snore and to the quiet that had learned how to be gentle.

“Daddy?” Emily murmured, surfacing. “Are we safe now?”

He looked out at the yard, at the gentle dark. He thought of courts and documents and orders that would always exist because something had once gone wrong. He thought of their house, which had been a stage for harm and then a workshop for repair. He thought of the sunlit square on the floor in the afternoon, how it had become a kind of clock for them, proof of the day turning.

“We are,” he said. “We are.”

That summer they planted tomatoes in bright orange buckets because the ground in the back was too rocky to bother with. The tomatoes took to the plastic like they’d been waiting for permission. Emily named them—Tiny Tim, Big Red, and Captain Marvel—and fretted over them the way she did over anything fragile learning to be strong. When the first one ripened, she ran into the house yelling and slid across the kitchen in her socks like a person arriving at a finish line. They sliced the tomato and ate it with salt over the sink, juice running down their wrists, neither of them polite about it because sometimes it was good for a house to hear laughter that wasn’t trying to be small.

Sometimes, when Daniel went to the basement for laundry, he caught sight of the old nylon brush in the corner where it had skittered the day everything changed. He did not throw it away. He did not leave it out, either. He put it in a clear plastic bin with the hardware from the pantry latch, labeled it in his careful block letters—REMINDERS—and slid it onto a shelf. It mattered to remember. It mattered to not make shrines to pain.

On the Fourth of July, they spread a blanket on the town green and watched fireworks paint the old courthouse in red and gold. Emily covered Rocket’s ears and told him he was safe, and Daniel watched his daughter reassure the world and felt something in him settle that had been jangling for months. “Want a popsicle?” he asked, and when she said yes he came back with two and the knowledge that some nights were so ordinary they tricked you into calling them perfect.

In August, during their last session before Dr. Martinez tapered therapy, Emily sat on the rug and drew a house with big windows and a dog that looked suspiciously like Rocket if Rocket had been drawn by a realist. “What’s different about this house?” Dr. Martinez asked gently.

“It’s mine,” Emily said. She added a square on the floor with lines for sunlight. “And the sun reaches the brush now.” She looked up at Daniel and smiled. It wasn’t a smile that asked for permission. It was a statement.

They celebrated with milkshakes at the diner off Route 1, under a framed photo of a marching band where everyone’s hats were slightly crooked. Emily held her glass with two hands like she was cupping something warm even though it was cold. “When I get older,” she said, “I want to help other kids talk.”

“You already do,” he said.

School started again with backpacks and sharpened pencils and the smell of a hallway waxed to within an inch of its life. On the first day, Daniel stood outside the classroom door with the other parents and felt a wave of gratitude so sharp it was like an ache. Ms. Whitaker greeted each child by name, making a joke about the weather as if it were a person they all knew. Emily hung her backpack on a hook and turned to him. Her mouth was steady. “See you after,” she said.

“After,” he said, and walked back to his truck feeling like a man who had fought a fight that mattered and, by some combination of luck and love and law, had won.

There would be other fights. There always were. But that morning, the light over West Haven was again the kind of light that made even ordinary things look briefly blessed. It reached the floor in a square and turned; it reached the brush in the corner and kept going. It found them where they were and did not judge. It did what light does: it made things visible. And once you saw, you didn’t go back to not seeing.

That was the difference, he knew now, between promising to protect someone and actually doing it. It wasn’t one heroic moment, one shout, one slammed door. It was a thousand small acts, performed in ordinary time, that added up to a different kind of life. It was a man leaving work early not because he sensed a crisis but because he wanted to be there to set a stool at a counter. It was a girl learning that hunger was a feeling, not a punishment. It was a house that learned the shape of their new laughter and, like the maple out front, put on new leaves right where last year had been empty.

In the fall, when the maples went bright again, Daniel stopped at the same exit he had the day everything changed and bought mint‑chip on purpose. He drove home in the early light, pulled into their spot, and carried the paper bag inside. Emily looked up from her spelling homework at the table, her hands unbandaged and ink‑smudged and sturdy. “You got ice cream,” she said, not surprised.

“I did,” he said. He set it on the counter, grabbed bowls, and took down the sprinkles. They ate before dinner just because they could. Rocket stole a lick when no one was looking and then looked extremely pleased with himself when someone was. Later, when Daniel washed the bowls, Emily leaned against the doorway and told him Ms. Whitaker had started a unit on fables and that she wanted to write one about a brush that kept trying to be a sword until someone taught it to make light instead.

He turned, water running over his hands, and memorized her face as if light itself were a language he could finally read. “That,” he said, “is a story I’d like to hear.”

She began it there in the kitchen, words bubbling sure and clear, and the house listened the way houses do when they’ve learned to trust the people inside them. Outside, the maple let go of a single red leaf. It twirled down like punctuation and landed on the porch where, someday, someone else would sweep it away without thinking about the luxury of such an ordinary act. For now, it could stay. For now, everything could.